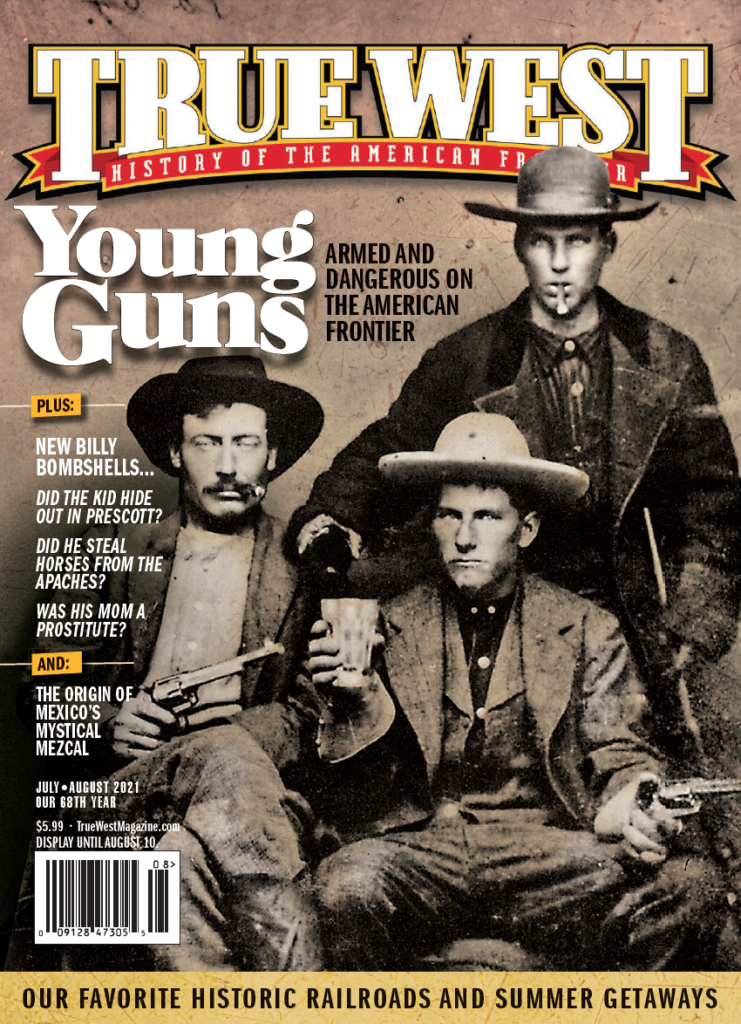

The well-known story of the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad and the Irish and Chinese men who built it has been recounted many times, but the role of women in the development of America’s railroads has been mostly overlooked, despite the development of the academic discipline of women’s history since the 1960s. Chris Enss’s Iron Women: The Ladies Who Helped Build the Railroad (TwoDot, $19.95) is a great introduction to the overlooked topic. Her subjects, who lived from the mid-19th century to the late-20th century, range from the first women telegraphers and female industrial engineers and inven-

tors to madams, outlaws, writers, illustrators, models, poets, architects and, even, railroad leaders, including Sarah Kidder, the first woman president of an American railway, California’s Nevada County Narrow Gauge Railroad.

As a historian, Enss is always seeking to uncover new subjects to profile, and diehard rail history fans will discover within the pages of Iron Women the stories of women whose lives and accomplishments should have been celebrated many decades before. I was most interested in the women who were industrial designers and inventors, women who understood engineering, and the importance of practical solutions to an industry that critically changed the lives of every American who benefitted from the growth and development of America’s railroads. In her introduction, Enss writes that women “provided services essential to the efficiency and effectiveness of the business and transformed the railways from an industrial tool of hauling material and equipment to a refined means of travel.”

In 2021, an era in which STEM educations and careers are promoted and encouraged for young women across the United States, these inventive women in Enss’s Iron Women stand out as role models: Eliza Murfey, holder of 16 patents for railroad bearings and self-lubricating packings; Nancy P. Wilkerson, inventor of the cattle car; Mary Pennington, patented creator of the refrigerator boxcar; Olive Dennis, a pioneering passenger railcar engineer; and Mary Colter, the great architect of the Fred Harvey Company, whose legacy of designs across the West that remain standing and in use are a lasting testament to her groundbreaking role in the railroad hospitality industry.

Enss knows her audience and her format, and for anyone who loves American railroad history, her Iron Women opens new doors to our understanding of American industrial history and the role women played in the rail industry, including its freight, passenger, hospitality and rolling stock history. Many publishers allow their authors to publish history books without footnotes or a bibliography, but Enss’s volumes of history always include her research—and in this era of the undocumented 24-hour news cycle and conjecture history, that is a breath of fresh air. What’s next from Enss? Maybe “Hard Rock Women” or “Working Women of the Timber Camps.” Whatever it is, I look forward to reading it.

—Stuart Rosebrook

Deadly and Dangerous in Kansas

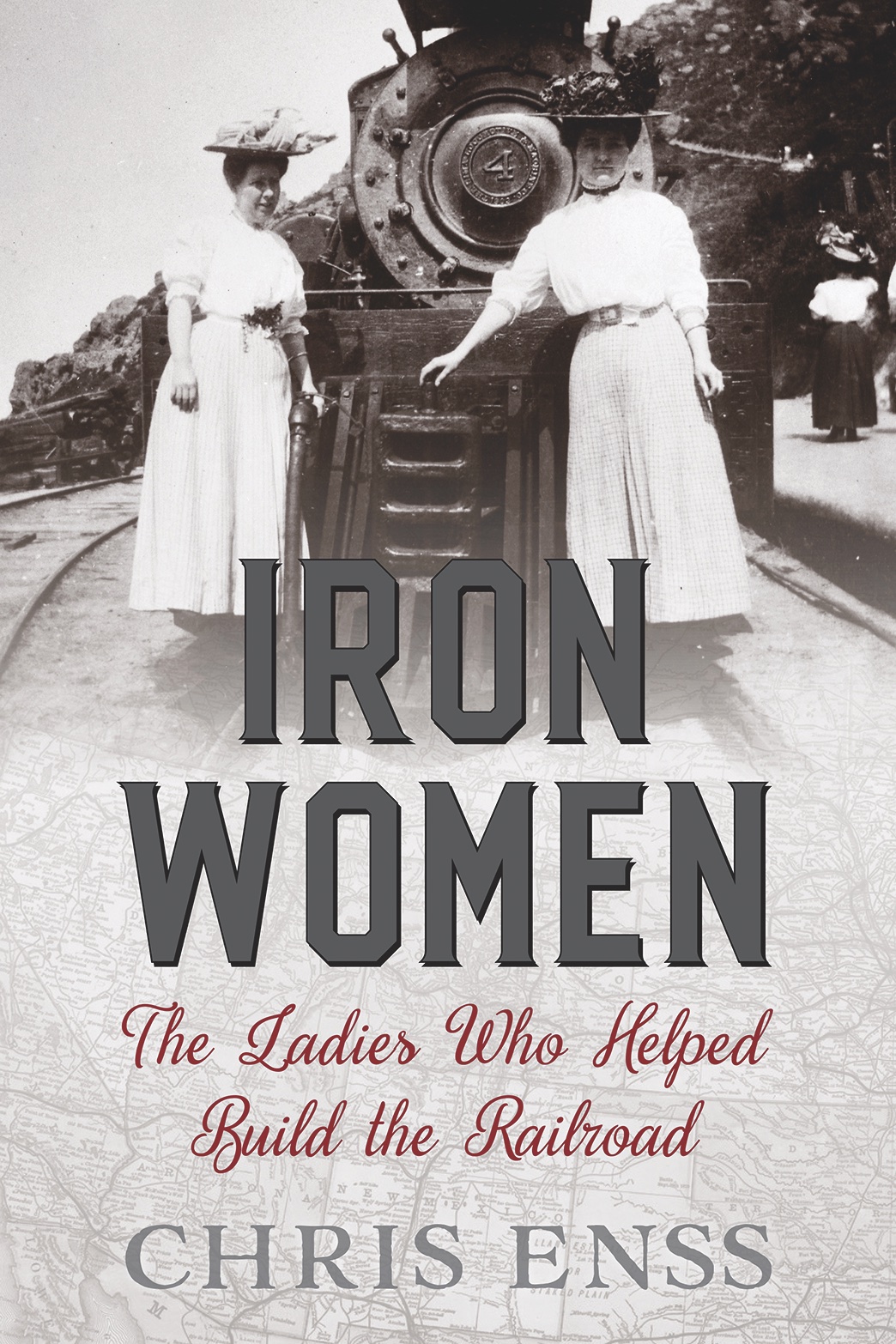

“A Desperado Without a Peer,” John Wesley Hardin Invades Kansas, 1871 by Doug Ellison (Western Edge Book Distributing, $15) is a slim book, but it takes a deep dive into Hardin’s account of his time around Abilene, Kansas, when Wild Bill Hickok was marshal. Ellison researched newspaper accounts, memoirs and local histories, comparing them to what Hardin alleged happened in Kansas. Did Hardin kill five Mexican cowboys in a gun battle? Did Wild Bill become friends with Hardin, allowing him to carry his guns in town? Did Hardin pull the so-called “border roll” on Hickok when he tried to take Hardin’s guns? How many other men did Hardin kill while in Kansas? Whether you have studied Hardin’s life or are unfamiliar with him, you will find Ellison’s easy-to-read book chock-full of information about Hardin and his dastardly deeds in Kansas.

—Bill Markley author of Geronimo and Sitting Bull: Leaders of the Legendary West

Dime Novel Hero

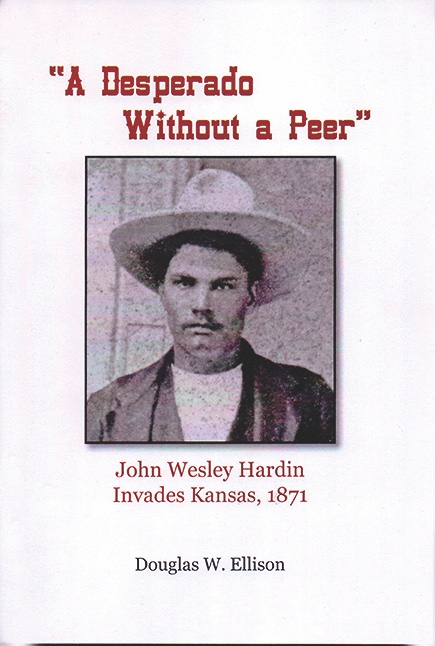

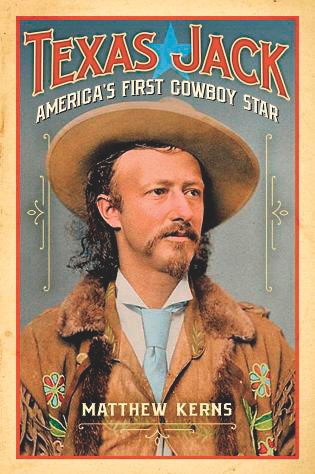

TwoDot Press continues its impressive run of frontier biographies with Texas Jack: America’s First Cowboy Star ($26.95). Author Matthew Kerns, a Tennessee-based historian and digital archivist, carefully explores the life of John “Texas Jack” Omohundro who rose to national prominence as a member of Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West shows after befriending Cody and Wild Bill Hickok. Later, Texas Jack was the subject of a series of Ned Buntline dime novels. Before his stardom, however, Texas Jack was a Confederate scout and spy and later a trail boss who led cattle drives on the Chisolm and Goodnight-Loving trails throughout the West. Texas Jack is a complete and thoughtful biography of a recognizable, but little-understood figure of the American West.

—Erik J. Wright, assistant editor of the Tombstone Epitaph

A Breed Apart

While 19th-century soldiers wore uniforms and some gained the title of hero, military wives who ventured with their husbands into the Arizona Territory are the true heroes. Their stories of hardship, as recounted by Jan Cleere in Military Wives in Arizona Territory: A History of the Women Who Shaped the Frontier (TwoDot, $19.95), are surprising, hard to believe, and yet, amazing. How they managed to survive in such a harsh environment is humbling. Some houses had only dirt floors, others wooden planks where all manner of venomous critters lived underneath. For some women who would finally get their homes fixed to their liking, then a higher-ranking wife would decide to move in. Frustrating, no doubt. But there were also women who loved the adventure and looked forward to the next posting. Their stories are truly inspiring.

—Melody Groves, author of When Outlaws Wore Badges

Indisputable and Unjustified

Most would agree that a battle becomes a massacre when the loser attempts to surrender, and the victor continues the slaughter. In Roger Nichols’ Massacring Indians: From Horseshoe Bend to Wounded Knee (University of Oklahoma Press, $24.95), the author broadens the definition to include winter attacks, destruction of food supplies and property, and assaults that hazard non-combatants. On a small scale he brings home the full horror of warfare in the 19th and 20th centuries when whole cities were put to the torch. This account is a necessary counterbalance to TV and B-Westerns where the gallant and ever victorious cavalry defeats the savage Indian.

—Doug Hocking, author of

Terror on the Santa Fe Trail: Kit Carson and the Jicarilla Apache

Rough Drafts

Illegitimi Non Carborundum

At the upcoming Western Writers of America Convention in Loveland, Colorado, I will moderate a panel titled “Writing the West in the Age of ‘Enlightenment’ or Who Owns History?” with historians Jane Botkin, Terry Del Bene and Linda Wommack. I expect we will have a very lively conversation.

To prepare for the panel, I have reflected on this question and considered if during my academic or professional career I have ever had someone challenge me on the ownership of history. Just the idea that someone can own history is as ridiculous as it sounds.

Conversely, can someone reserve the right to retain their story for themselves, for their family, for their own use? Of course, it happens every day, and is at the foundation of the First Amendment. I have encountered it many times in my own work. My late father, Jeb Rosebrook, who had a six-decade-long writing career, most of it in Hollywood, would often say when queried about different aspects of his work, “I’m not ready to share that; I’m saving that for my book.” He is not the only one I have heard say that. As a writer, I have been on the short end of many of those conversations. As a historian and journalist, I emphatically respect a subject’s right to their story. Unfortunately, many individuals’ stories go unrecorded, and we are the lesser for it. (So please, record your story. You will be happy you did, and so will your family.)

I have been privy to stories of writers (in all mediums) being passed over for work because their perspective was not correct for the job because of their gender, race, creed, ethnicity or sexuality. Even worse, a modern, pharisaical generation of journalists and scholars accuse their colleagues and competitors of intellectual theft, threaten legal action or terminate contracts because they are not “enlightened.” It is a tragic moment for all of us who believe in the Constitution and the ideals of the First Amendment and free speech.

So what is my solution? Remain independent, truthful, fair, diligent, honest and accountable.

—Stuart Rosebrook

Building Your Western Library

Saddle Up with Western Ranch Historian and His Favorite Authors

Spur Award-winning author and historian Jefferson Glass grew up in the ranch country of southeastern Oregon. He relocated to Wyoming 40 years ago, which further expanded his interest in cowboy culture and ranching history. His latest work, EMPIRE: The Pioneer Legacy of an American Ranch Family, arrived in bookstores the first of November from TwoDot Books.

When you have finished reading EMPIRE, he recommends you read a few of his favorite fireside companions:

1 The Day of the Cattleman (Ernest Staples Osgood, University of Chicago Press): Osgood shares his observations on the development of the cattle industry during the open range years. He cuts through the romance of novels and movies and tells the story as he saw it a century ago.

2 Charles Goodnight: Cowman and Plainsman (J. Evetts Haley, University of Oklahoma Press): The author conducted multiple interviews of his crusty subject, and combined them with decades of research into the most unvarnished saga possible for the era.

3 Longhorns North of the Arkansas (Ralph F. Jones, Naylor Company): Jones compiled this book 40 years after Osgood’s, and does not mince words in describing how powerful cattlemen controlled the open range economy and “free grass” from Texas to Canada.

4 The Ranchers: A Book of Generations (Stan Steiner, Alfred A. Knopf): Steiner compares the stories of fortitude and lifestyles of multigenerational Western ranch families scattered across the West from the 19th-century frontier to 20th-century modern ranching.

5 The Ladder of Rivers: The Story of I.P. (Print) Olive (Harry E. Chrisman, Dawson County Historical Society): Another great picture of life in the saddle over a century ago, Chrisman’s story centers around Print Olive and the founding of the Olive Brothers’ Ranch in Nebraska.