The American West has its myths, but it is also steeped with genuine characters and events which we can identify with, even more than 200 years later.

When you hold a material object linked to that history, or view a photograph that captured a historical moment, you’re almost instantly transported to that significant day. And you can say to all those naysayers, “Yes, this did happen, and here’s some of the proof.”

Just like the fetishes Zuni women pointed to on their storyteller necklaces to indicate characters in their stories, collectibles can help bring stories alive for so many people. Words have staying power, but they can be bolstered by holding up a piece of history, such as Red Cloud’s peace pipe, which he gifted to Doc Irwin, an Indian agent who served at Red Cloud Agency in Nebraska during the late 1870s. Red Cloud called Irwin the “only Indian agent that we’ve ever had who we really trusted,” the Ogala Lakota chief wrote in a letter to President Hayes.

Wes Cowan tracked down that letter helping to confirm that Pat Smith of Livermore, California, likely did possess Red Cloud’s peace pipe, given to her great-grandfather James Irwin and eventually passed down to her. He did so as one of the star investigators of PBS’s History Detectives, a show “devoted to exploring the complexities of historical mysteries, searching out the facts, myths and conundrums that connect local folklore, family legends and interesting objects.”

Wes appraises Western Americana photographs and collectibles for not only History Detectives, but also Antiques Roadshow (slogan “Behind every treasure lies a story”) and as the founder and owner of Cowan’s Auctions in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Luckily for us, the Louisville, Kentucky, native found the time to share with us the coolest collectibles he has come across since 1995, when he left academia and his work as curator of archaeology at the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History to become an independent appraiser.

Luckily for all of you, Wes’s mother filled the home he grew up in with Victorian antiques, nurturing in him a love for the stories hidden inside our material possessions, stories that, when revealed to us, become a part of our history too.

—The Editors

Simply too many “stars” in the Western firmament are collectible! I’ve plucked some high-priced items out of the Cowan archives, even though most of us don’t have the disposable income to collect such expensive Western artifacts. Still, it’s fun to dream!

George Armstrong Custer’s Folding Camp Chair

When the noted frontier photographer David F. Barry moved his studio from Bismarck, North Dakota, to Superior, Wisconsin, in 1890, he brought with him his collection of glass plate negatives and a sizeable group of Indian Wars artifacts he had collected over the years. After Barry’s death, most of his negatives were purchased by the Denver Public Library and are today part of that institution’s Western History Division. His collection of artifacts were purchased and donated to the Douglas County Historical Society in Superior.

Among the collection was a worn camp chair given to Barry by the postmaster at Fort Abraham Lincoln. In a famous photograph, George A. Custer is seen sitting in such a chair with Bloody Knife, his favorite Arikara scout, crouching beside him.

The provenance accompanying the chair was fairly conclusive. Barry’s handwritten catalog of his collection records “item number 63 Genl Custer’s Army Camp Chair received from Mr. Cannon. Postmaster Fort Abraham Lincoln.” In addition, the chair was noted in newspaper articles in 1897, 1903 and 1934 as being part of the Barry collection, and it had been photographed in various exhibits and illustrated in publications dealing with Barry and his life on the frontier.

In 2004, the Douglas County Historical Society invited me to visit Superior to assess its Barry Collection. Unfortunately, sometime in the 1970s, most of Barry’s Indian artifacts were stolen and never recovered. The chair, along with hundreds of original Barry photographs, remained. The Society’s board recognized that the chair had little to do with their main focus—the history of Superior and Douglas County—and made the decision to sell the chair at auction. My company was chosen to market this remarkable artifact.

Once the bidding opened, determined collectors from across the U.S. showed their interest. When the hammer fell moments later, the chair had sold for more than $56,000.

Bloody Knife’s Discharge Paper, Signed by George Armstrong Custer

In the same auction, Cowan’s was fortunate to include remarkable artifacts collected by the late Col. Alfred B. Welch, a turn-of-the-20th-century businessman in Mandan, North Dakota, who became interested in the Sioux and their involvement with the Custer massacre. Over the course of a number of years, he interviewed many of the Indian participants in the battle and collected artifacts related to the event.

Included among his collection was a folded and much worn military discharge for Bloody Knife, Custer’s trusted scout, for the six-month enlistment period beginning May 30–November 30, 1874. Bloody Knife was 34 years old at the time, and described as five feet and eight inches tall with “dark” complexion, and with “black” hair and eyes. The discharge paper was signed by two notable 7th Cavalry figures: G.A. Custer, as a brevet major general commanding, attesting to the character of Bloody Knife, and Lt. James C. Calhoun, as Chief of Indian Scouts. Calhoun noted: “An excellent and reliable scout.”

Bloody Knife was born about 1840, the product of the marriage between an Arikara woman and Hunkpapa Sioux father. He grew up in the same camp as Gall, the Hunkpapa war chief. As a mixed-blood, Bloody Knife’s relationship with Gall was marked by animosity and, ultimately, extreme hatred. Forced from the Hunkpapa camp at an early age, Bloody Knife would never forget the brutality he experienced.

By the early 1860s, Bloody Knife was livingat Fort Berthold in North Dakota and hadfound employment with white traders serving as a guide, interpreter, mail carrier and hunter. In 1866, when President Andrew Johnson signed the Indian Scout Enlistment Act authorizing a force of Indian Scouts, Bloody Knife was a perfect candidate; he first enlisted on May 1, 1868. He’d serve a total of 11 hitches.

The term of enlistment for Indian Scouts was six months. They received the same pay and allowances of regular white troops, and the government provided their quarters and rations. The scouts were commanded by white officers, were not subject to military drill and couldbe discharged by the Department Commanderat will.

By the time Custer arrived at Fort Lincoln in Dakota Territory in the spring of 1873, Bloody Knife was a seasoned scout. He quickly became Custer’s favorite, in spite of his penchant for violence, often brought on by his fondness for spirituous liquors. He served with Custer on the Yellowstone Expedition of 1873 and as one of the chief scouts on the Black Hills Expedition of 1874, and again on the Bighorn-Yellowstone Expedition of 1876.

During the historic Battle of the Little Bighorn, Bloody Knife, along with the other Arikara and Crow scouts, had been instructed by Custer to drive off the herds of Indian ponies in the hostiles camp. When Reno’s command of 140 troopers struck the southern end of the main village, Bloody Knife was there.He was mounted and close to Reno when hit by one or more bullets, one striking him between the eyes.

Like the Custer camp chair, the discharge paper has impeccable provenance. The businessman Welch acquired it on September 7, 1933, from F.B. Zahn of Fort Yates, South Dakota, for $5. Zahn, in turn, had acquired it from Mrs. Iron Horse, half-sister of Bloody Knife, for an undisclosed sum.

The discharge paper was sold with Zahn’s original typed letter to Welch offering the discharge for sale, another typed transmittal letter from Zahn finalizing the sale and a newspaper clipping from the Bismarck, North Dakota, paper announcing Welch’s purchase. Carrying a pre-sale estimate of $10,000-15,000, when the hammer dropped on this incredible survivor, it sold for $43,700.

Alexander Gardner Photographs Taken Along the Route of the Kansas-Pacific Railway and of the Fort Laramie Treaty

Photographer Alexander Gardner is not a household name. Civil War collectors certainly are familiar with his work as one of the “operators” for Mathew Brady. Gardner captured some of the most enduring images of the war, including haunting images of the dead at Gettysburg. He received precious little credit from Brady and left his employ before the end of the war, to open his own studio in Washington, D.C.

After the war, Gardner received a commission from the Kansas-Pacific Railroad to photograph scenes along the line for a proposed southern trans-continental rail route. In 1868, he traveled West from St. Louis, photographing a variety of scenes in Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming and Montana. He produced a remarkable series of large 14-by-20-inch photographs and stereographs of frontier outposts and settlements. While working under the terms of his commission to the railroad, Gardner undoubtedly had commercial possibilities in mind. For whatever reason, the series did not capture the public imagination, and large quantities of the images from the excursion were never produced. Today, one most often encounters Gardner’s stereographs; his large-format images are incomparably rare.

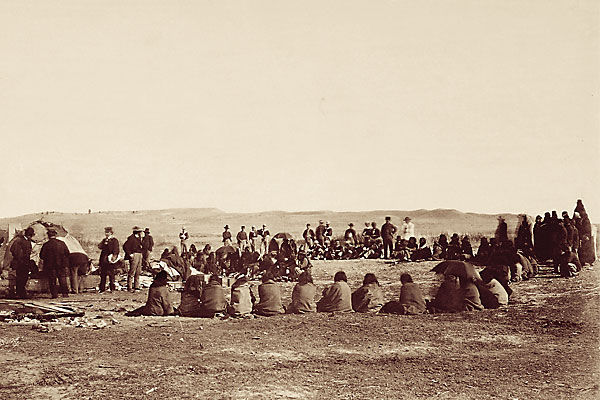

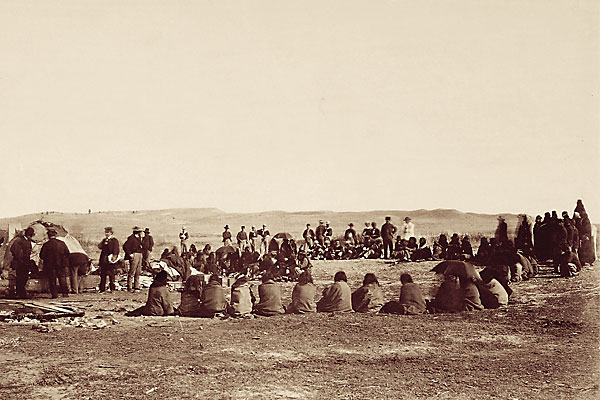

Arriving in Fort Laramie, Wyoming Territory, in April 1868, Gardner witnessed a council between U.S. Peace Commissioners and various Sioux bands, the Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Crow and Northern Arapaho. The resulting treaty guaranteed safe passage for white settlers traveling overland on the Oregon Trail in return for annual annuities to be paid to the Indians. The government also recognized the Indians’ rights to the Black Hills and other territory. This uneasy peace lasted only a few years as gold was discovered in the Black Hills in 1874. White miners poured in, and War on the Plains again broke out, culminating in Custer’s disastrous defeat on the Little Bighorn in June 1876.

Gardner photographed a number of the participants in the negotiations and exposed several large format plates. Included in his work was an important image of the Crow delegates seated in an arc with Peace Commissioners to the left, most standing and distributing gifts.

The Crow had been signatories to an earlier 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty. After years of seeing its articles ignored by white settlers and miners, they were skeptical of the promises made in 1867. During the negotiations, Bear Tooth, a Crow delegate, questioned the integrity of the treaty: “Your young men have destroyed my timber and green grass and burnt up my country. Your young men have killed my game, my buffalo. They did not kill it to eat it. They left it where it fell. Father, were I to go to your country to kill game, your cattle, what would you say. Would you not declare war?”

The Crow nevertheless signed the treaty.

One of an important group of Gardner images deaccessioned by the Western Reserve Historical Society of Cleveland, Ohio, this photograph hammered in for $46,000 at a Cowan’s auction in 2006.

Table of Distances for the Stage Line Between Atchison, Kansas, and Salt Lake City, Utah

Right up at the top of my favorites of Western collectibles I’ve been fortunate to handle was a small, five-by-three-inch, four-page publication titled, “From Atchison, Kansas, to Great Salt Lake City, the Route Passing Through Denver City, thence by the Cherokee Trail along Cache La Poudre River, Through Laramie Plains, by Fort Halleck and Medicine Bow Mountains, Bridger’s Pass and Fort Bridger, to Great Salt Lake City.” Slote & Janes of New York published the pamphlet in 1863, and Ben Holladay was credited as the proprietor. The two interior pages list the names of each stagecoach stop between Atchison and Salt Lake, along with their distances apart.

For a brief period between 1860-65, the Overland Daily Stage was the principal means of delivering mail between the Missouri River and California. The route from Atchison, Kansas, to Salt Lake City, Utah, was the main source of contact between the East and the various military forts and trading posts and the burgeoning Mormon population in Utah Territory. Ben Holladay—the Stagecoach King—operated the line, which was equipped with coaches manufactured by the Concord Stagecoach Company and drawn by four horses. These horse-drawn coaches left Atchison and arrived in Salt Lake City 18 days later.

A classic “survival,” this little bit of ephemera almost certainly was produced in tiny numbers, a fact that was reflected in our search that revealed no extant copies. Western collectors bid it up to $4,400.

Carte de Visite Photograph of Wild Bill Hickok

Surely no figure is more identified with the rough and tumble days of the West than James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok (1836-1876). A legend during his lifetime, his stature grew after being gunned down in a Deadwood, Dakota Territory, saloon while playing poker. His hand—allegedly pairs of aces and eights, along with a queen—is the basis for the legendary “Dead Man’s Hand.”

Cowan’s has been fortunate to handle a number of images of Hickok. While not the most expensive, my favorite is a small carte de visiteof him, likely taken during the Civil War when he was serving in the 8th Missouri State Militia as a scout and spy. Descended directly in the Hickok family, the image shows Bill in less than distinctive Western garb, but nonetheless captures his unique visage. One of two known to exist, this example fetched $28,750 at a Cowan’s auction in 2007.

Wes Cowan is founder and owner of Cowan’s Auctions, Inc. in Cincinnati, Ohio. An internationally recognized expert in historic Americana, Wes stars in the PBS series History Detectives and is a featured appraiser on Antiques Roadshow. He can be reached via e-mail at info@cowans.com