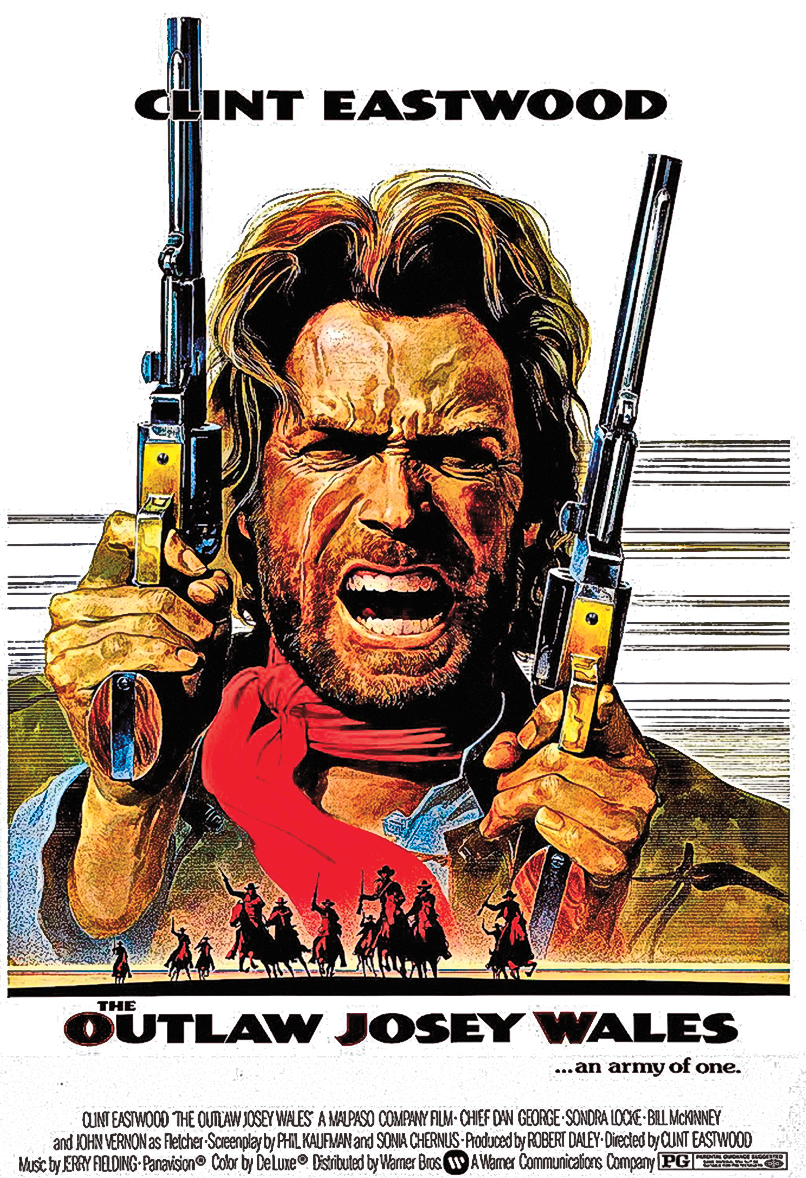

– All images courtesy Warner Bros. –

In the latter quarter of the 20th century, the only person indispensable to Western film was Clint Eastwood. Losing a Peckinpah or a Leone would have been bad, but without Eastwood, the genre would have been deader than the Daltons. This year marks the 40th anniversary of one of Eastwood’s finest Westerns, The Outlaw Josey Wales. Some consider the 1976 film one of the best Western movies ever.

When Forrest Carter’s first novel was published—an initial press run of 75 copies—he was unaware that Eastwood’s Malpaso Company did not accept unsolicited material. But Producer Robert Daley was so moved by the cover letter accompanying The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales that he read the book. He then told Eastwood, “This thing has so much soul to it that it’s really one of the nicest things I’ve read.”

The actor-director agreed. He bought the

film rights.

The movie is an unconventional Civil War and post-war story, focusing not on generals and battles, but on the aftermath of the guerilla war between the North’s Red Legs and the South’s Bushwhackers, and the abuse of Indians who had sided with the South. Josey Wales, Eastwood’s character, is a farmer who joins the Bushwhackers after his wife and son are murdered by Red Legs. When the Civil War ends, he refuses to sign a loyalty oath. He and Jamie (played by Sam Bottoms) set out, tracked relentlessly by the Red Leg commander (Bill McKinney) and a Judas (John Vernon).

“He knew what he wanted, and he just grabbed it.”

The story contains not only grim elements and action, but also humor and beauty and endearing characters. Eastwood’s costar, Oscar nominee Sondra Locke, shares why the film is special to her: “It had a great story, a great hero too, and Clint was perfect for it. [In his] Spaghetti [Western] films, he had no attachment to anybody. He was a loner out for himself. In The Outlaw Josey Wales, he’d been victimized; he had a family that he’d lost. He was a man who responded to humanity, to other human beings. The Outlaw Josey Wales had a traveling band of colorful characters—all struggling for a dream. I think it was that soul in the film that made it special.”

Walter Scott, who began doubling Eastwood on CBS’s Rawhide series, was double and stunt coordinator on The Outlaw Josey Wales. He says scenes were shot all over the West: “We were in Utah first, for all the Indian stuff. Then down to Old Tucson [Arizona], then to Marysville, up by Sacramento [California] for all the stuff with the raft.”

There, the Red Legs are on a ferry, trying to catch up to Wales, when he shoots the ferry rope, sending the raft spinning down the river. “I had seven or eight stuntmen and horses on it,” Scott says. “We thought it would twist and turn, but that raft was so good, it didn’t move! They had to push the horses off, and I’m yelling at them, ‘Get off! Someone go into the water!’”

Eastwood had already directed five features by that time, including 1973’s High Plains Drifter, but he had not intended to direct this one. He hired Philip Kaufman, who had written and directed 1972’s The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid. Then problems developed between them on the set. Locke remembers, “Kaufman’s a good writer, and it was a really well-written script. [As a director] he was unbelievably slow; he would intellectualize everything. Clint was just the opposite. Clint just would run on his gut. He knew what he wanted, and he just grabbed it.”

“Clint fired him after two weeks and took over,” Scott tells True West. “The Directors Guild passed a law after that and said an actor couldn’t do that; it’s called the Eastwood Rule. Clint started all over again, and we still finished two weeks under schedule.”

Scott remembers the big shoot-out at the end, with Wales and his friends in the cabin, being attacked on all sides by the Red Legs, a sequence that would normally take several days to film. “Clint gave me a day with the stuntmen to rehearse and lay out every piece,” Scott says. “He said, ‘Tell me what you’ve got.’ ‘I’ve got some guys going around the hill; they’ll fall the horses down. The guy up on top, he’s going to cave the roof in. Other guys are riding by—we’ve got a jerk wire on one guy.’ We filmed it all in half a day. End of the day, I’m [paying off] the stuntmen, Clint walks by, and says, ‘Hey boys, whatever he gives you, just double it, because it was a helluvah day!’”

If the characters in The Outlaw Josey Wales dreamed of changing their lives,

so did the author of the book that inspired the movie. Carter’s success was his undoing. He was exposed as Asa Carter, a once powerful leader of the Ku Klux Klan. Although he, unlike Wales, did not succeed in leaving his past behind, he did leave a heartfelt literary legacy.

Locke cherishes her memories of cast members, from character actors Sheb Wooley and Royal Dano, to 79-year-old Paula Trueman, “… who would do somersaults to make Clint laugh,” to Chief Dan George and despicable Bill McKinney. “Chief Dan was just the way he was onscreen,” Locke says, “and Bill McKinney was just the opposite, a funny, funny guy.”

Henry C. Parke is a screenwriter based in Los Angeles, California, who blogs about Western movies, TV, radio and print news: HenrysWesternRoundup.Blogspot.com