— Courtesy Heritage Auctions, December 11-12, 2012 —

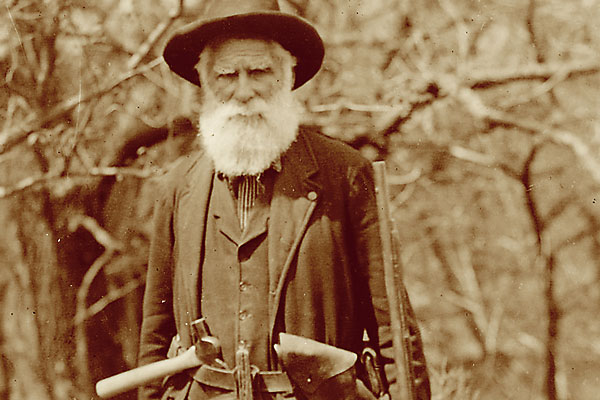

Louis Mueller always said both Sooners and Suckers participated in the 1893 Cherokee Strip Land Run, and my impression was that he put himself in the latter category. Louis, a German immigrant, was my mother’s father. He had just turned 21 at the time of the land run.

The race to make dreams of land ownership come true started on a hot and dry September day. Dust, whipped by the wind, swirled into the air, making September 16, 1893, feel unbearable. That did not stop some 150,000 people from every state and territory in the nation and abroad. They sprinted forward on horses, in buggies and wagons, even on bicycles and railway cars, as a starting cannon boom rang out, at the stroke of noon.

— Louis Mueller photograph courtesy Joe short —

The Cherokee Strip Land Run in the northwest section of what is now Oklahoma was counted as one of the largest single competitive events in world history. It easily topped the three Oklahoma land runs that came before it. The run had 115,000 registrants, but accompanying friends and family running the race brought the number closer to 150,000. To say this run was competitive is a gross understatement as the strip offered only 42,000 parcels. America was in the grip of the worst economic depression it had ever experienced, swelling the number of expectant land seekers that day. Coupled with poor planning and inadequate enforcement by federal agencies, the run brought not only chances to make dreams come true, but a race that bred fraud, chaos, widespread suffering and even death.

Those settlers who waited for the cannon boom before rushing into the opened lands were known as Boomers. But Sooners sneaked onto the land early, slipping by soldiers patrolling the borders and interior. One man bribed a soldier $25 to be hidden in a hole on a claim the Friday before the run. When he emerged, his claim was staked by others.

— Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration —

My Grandfather’s Dream

At 21, Lür Mueller had lived in the U.S. for eight years and Americanized his name to Louis. He dreamed of feeling that Cherokee Strip wind sweeping through tallgrass prairies and across fields of wheat.

Louis’s family came from Bremervörde, Germany. An unpaid bill for a windmill built by his father Fred caused the family to leave in 1885 for America, arriving in Hoboken, New Jersey, by ship and Missouri by rail.

Louis worked in Sweet Springs for his father, 10 hours a day, 15 cents an hour. After they built two buildings, Louis said, “Well, we done it. Him and me alone.”

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Louis saw opportunity when he learned that the federal government had renounced its treaty with the Cherokees and opened up the Cherokee Strip. After the Indian Removal Act of 1830 had forced the removal of the Cherokees from southeastern U.S., Cherokees marched in 1838 on the “Trail of Tears,” which resulted in roughly 4,000 to 6,000 deaths. Allotted land 226 miles from east to west and 58 miles north to south, the Cherokees had access to hunting grounds to the west, although they lived to the east. They leased outlet land to cattlemen, and three railroad lines ran through. Eventually public opinion demanded opening the outlet to settlers.

Squalor in Arkansas City

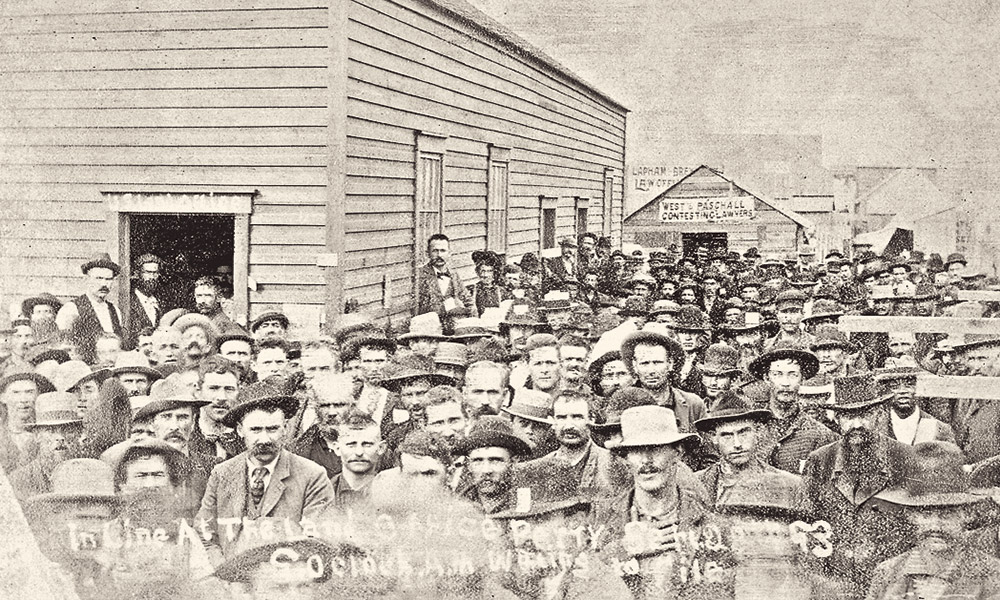

Seeking a claim on the strip meant obtaining a $14 registration. To be eligible for a homestead, either man or woman had to be 21 years of age or head of a family (which caused some hasty marriages) and a U.S. citizen or declaring intentions to be one. Folks could register at booths, four on the Oklahoma southern border and five on the northern Kansas border. Registration began on Monday, September 11, with booths open 10 hours daily.

Tens of thousands showed up at these booths. Lines were often a mile long, four abreast, with people waiting for days. The intense heat and bad water caused an epidemic of dysentery at one booth. Sunstroke was a problem everywhere, with numerous deaths reported.

On September 14, a wire from Arkansas City, Kansas, was sent to President Grover Cleveland: “7,000 people are now in line and thousands more arrive on each train. A conflict…is imminent unless the system is abandoned.”

— Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration —

On that date, a Rock Island train crossing the strip was robbed—not of money or gold, but of water and ice.

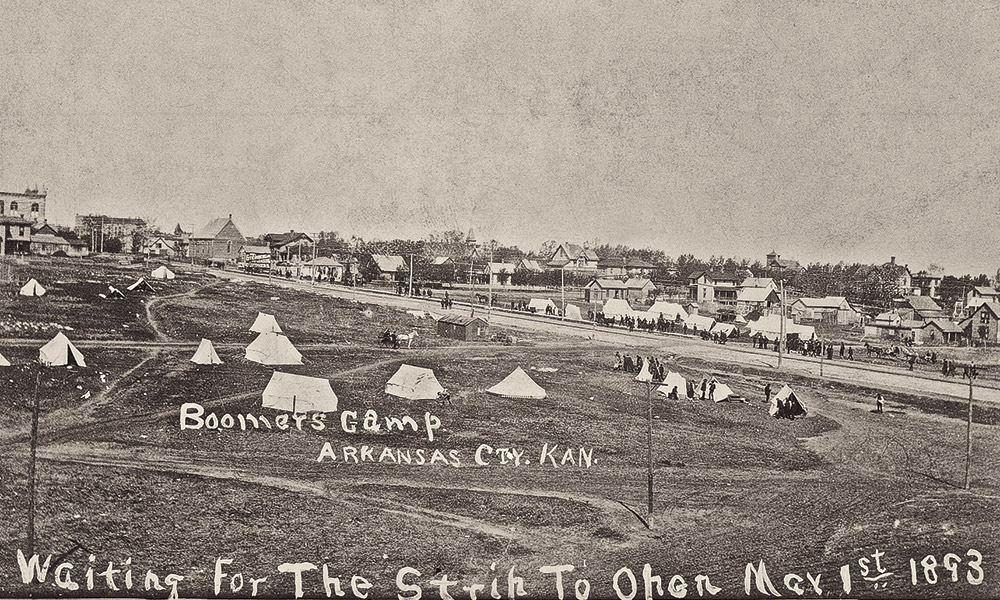

Louis brought his oldest brother Henry and his friend Fisher along for the Cherokee Strip Land Run. They headed for the largest registration point, Arkansas City. “We saw lots of prairie schooners coming down from Kansas with slogans ‘Oklahoma or Bust,’” Louis noted. “Most of them went back busted.”

The huge mass of people headed for the run created an extreme shortage of feed for horses. That almost ended the journey for the Mueller party, traveling with a saddle horse and one pulling a spring wagon. But a substantial “nip” of whiskey Louis gave a man from a dry state who had hay got enough feed for the horses to continue.

Fisher did the cooking. “Mostly fried potatoes,” Louis explained, “but once in a while he’d cook a chicken. Where did he get it? Well, he didn’t buy it.”

— Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration —

When they arrived in Arkansas City, they were shocked at the squalor—people nearly starving and living in makeshift tents. Louis proclaimed how tiresome he felt, standing in line all day. “One man,” he said, “sawed up some two-by-fours into two-foot pieces, then cut off a 12-by-12-inch piece, nailing it on top. Looked very comfortable when you’d been standing awhile. Sold ’em for 50 cents a piece.”

After two days in line, Louis got within five men of the window when the office closed. He and the other five slept on the ground where they stood, to be first in line the next morning. They were.

After enduring registration, Louis decided he’d earned a beer and went into a saloon. “Well, a fellow came up to me and said if I wanted some really good beer, to come with him. He led me up a stairway to a door on the second floor. There were long tables, with men playing cards,” he said. “I was no card player.”

Louis found the door locked. He had quite a time talking himself out of the gambling den. But his heavy accent, saying he didn’t know how to gamble, worked: “I didn’t get robbed, but I never got a glass of beer.”

— Courtesy Cherokee Strip Regional Heritage Center Archives —

Flaming Passions and Prairies

On the hot and unpleasant day of the run, the hard-baked soil had been pulverized into dust by the thousands and thousands of human feet and animal hoofs. The extreme wind that day kicked dust high into the air, causing lungs to wheeze and eyes to blur.

As wagons, horses and bikes lined up on both north and south borders, a bicyclist on a hill recalled: “The back of the line was ragged, incoherent…the front was a solid band of horses; some had riders, some were hitched to gigs… wagons, but to the eye there were only the two miles I could see of tossing heads, shiny chests, and restless front legs of horses.”

A Sooner jumped the gun and was shot by a soldier. A cannon at the eastern end gave the starting blast at noon. Soldiers’ rifles firing in the air carried on as far as sound could travel the length of the Cherokee Strip.

In one thundering moment, horse flesh cut loose. Many wagons quickly overturned or broke apart. People fell off horses and were trampled in the rush; one woman was killed when her horse fell on her. Riders on the jam-packed trains got injured jumping off. Broken arms, legs and necks were common.

At one steep 18-foot ravine, bicyclists were forced to quit. The ravine crippled many horses. One man’s thoroughbred racehorse became excited in all the turmoil, ran uncontrollably for 24 miles, then dropped dead.

Louis and Henry Mueller and friend Fisher started well, but after several miles, they saw a horrific sight—the prairie afire. People were burning to death.

Moving the horses to top speed, the Mueller party found a place where the fire was low. They drove along scorched, blackened earth and, luckily, made it out onto unblemished prairie. But soon, another fire raged into sight. “Those people that set those fires must have been some that were out in the lead. That was murder,” Louis said.

— Courtesy Linda Short Van Peenen —

My grandfather was right. Horsemen in the lead had dismounted and started fires to slow the advance of others.

Louis remembered how he “…finally located a nice piece of bottom land, and my hopes were up…there was a creek and trees and what looked like, at first, a big haystack…but there was a man sitting inside with a shotgun…apparently he’d built a sort of framework and covered it with loose hay. I could see where the grass had been cleared from the ground around it…and I could see a campfire burning down by the creek. The man called out ‘Stranger move on.’ When a fellow with a shotgun tells you to move on, you move on.”

The run for land had ended for Louis.

The majority of participants in the 1893 Cherokee Strip Land Run did not secure a claim. Some of the best land went to Sooners. Only about 20 to 30 percent of those who filed claims fulfilled their rights to keep the land: they survived the six-month residency, had no one else claim the land and made improvements.

As for Louis, he eventually married a German lady named Alvena and had three daughters. In 1919, they settled in Pawhuska, Oklahoma, where Louis designed and built homes, churches, the fairground buildings and grandstand, and the high school and gymnasium. He also built and operated the Travelodge, the first motel in northcentral Oklahoma.

In the 1920s, the discovery of oil on Osage land near Pawhuska made the Osages the richest people per capita in the world. It also brought great prosperity to builders, and Louis was hired to construct and renovate buildings and a museum for the Osage Nation, and ranches and homes for Osages.

One of the last homes Louis built was for Hotahmoie (John Stink). He was traditional in his beliefs, not wanting to live in a house and preferring to roam the woods. But the Osages authorized a car and a home for him. Louis enjoyed Stink, recalling, “He used to sit in his car and watch his house being built.”

Louis led a rich and full life. But once in a while, he was known to mutter, “That sure was a nice piece of bottomland on the Strip.”

Born on the Klamath Indian Reservation in Oregon and enrolled with the Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma, Cheewa James is the daughter of a German immigrant and a Modoc, and author of Modoc: The Tribe that Wouldn’t Die and Catch the Whisper of the Wind. A former television anchorwoman and reporter, she is the recipient of seven United Press International awards.