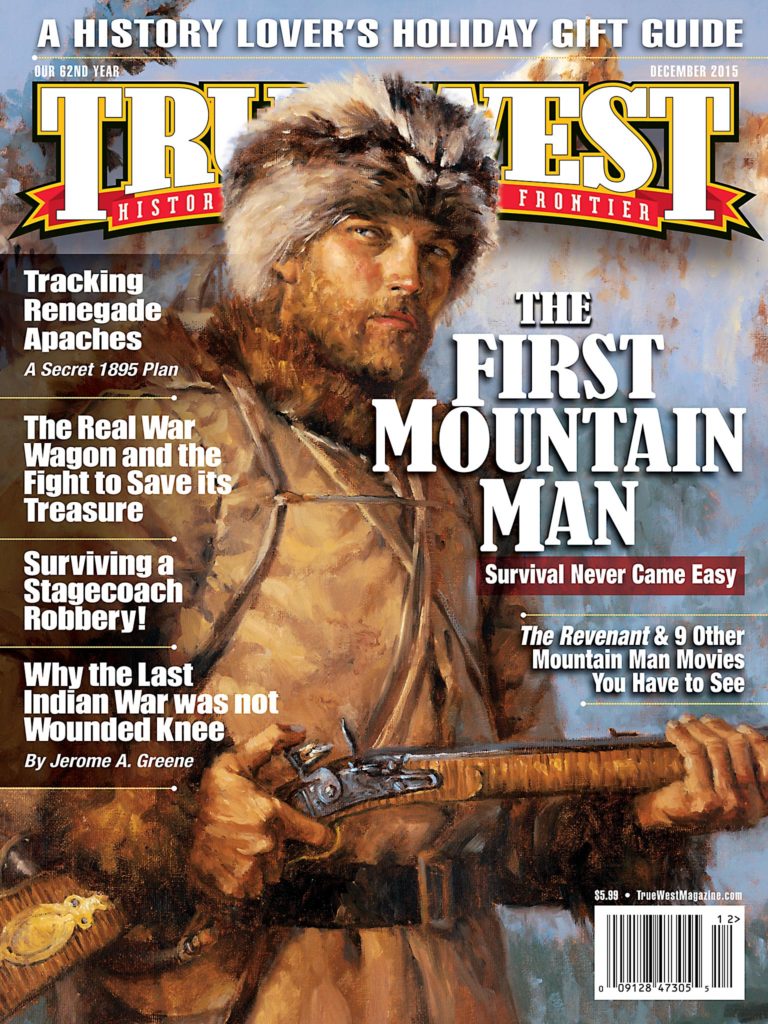

– True West Archives –

When Western traveler George Rutledge Gibson wrote how he and his companions prepared for a possible Indian attack in May 1848, he recalled that “flints were screwed in, pans primed and all things made ready for a fight.”

Frontiersmen took such knowledge for granted, but modern users can find these now archaic firearms challenging. Flintlock shooters become disconcerted when too big a charge in the pan creates too much flash, causing “flinchlock fever”—the pan’s flash makes you flinch, and your shot goes astray.

Why does this happen? Some flintlock shooters make the mistake of heaping their flinter’s flash pan full with priming powder.

The flintlock system is the longest-used method of firearms ignition, having lasted more than 200 years. In the heyday of blackpowder, soldiers primed their muskets with Fg (1F) blackpowder, which was taken directly from the musket’s paper cartridge. A soldier poured a small amount of his cartridge’s powder into the pan and then loaded the main charge and ball down the barrel. Rifle and pistol priming pans are smaller than those found in military muskets, so I advise you to stay with the finer FFFFg (4F) priming powder.

When pouring priming powder, you need only enough to burn through the touch hole into the main powder charge. Don’t pile the stuff as though you were filling a “heaping spoonful” of sugar. Likewise, don’t be stingy with your priming powder. A level or slightly-less-than-level pan is sufficient for good ignition. Otherwise, you will not only waste powder, but also suffer flinchlock fever.

The secret to shooting any flinter is to understand the gun and its place in the evolution of firearms (early 17th century to mid-19th century), and to enjoy the process. Although slow to load, flintlocks can be among the most fun guns to shoot.

For muzzleloading firearms, especially flintlocks, the fun comes in the steps required to load and make your shot count—not just blazing away as one might with a modern cartridge gun.

Flintlocks are a breed of their own and can be temperamental. If you follow a few simple steps to improve your flintlock handling skills, you will enjoy shooting these reflections of yesteryear much more.

First, make sure you have cleaned the touch hole with your vent pick, previous to loading. Once you have charged the flash pan, tip your firearm so that the powder in the pan falls into the touch hole. You can help it along by lightly tapping the side of the flintlock with the palm of your hand.

Be sure your flint stone has a sharp and well-angled edge. Once a stone’s edge becomes dull or its angle has worn away through repeated striking on the frizzen (striking plate), you will need to replace or to reshape the flint, a process known as “knapping.” Several muzzleloading suppliers sell flint knapping tools.

If you don’t own a flint knapping tool, your knife will also serve the purpose. You should give the striking edge of the stone a series of light, sharp taps with either edge of your knife blade until the desired angle is achieved. Don’t strike too hard, as the edges of these stones are generally brittle and will chip away easily.

Follow these simple tips, always wear eye and ear protection, and see if you don’t enjoy shooting a flintlock much more, while curing yourself of flinchlock fever.

– Carson’s Flintlock photo Courtesy Tim Peterson Family Collection, Scottsdale’s Museum of the West; Carson & Frémont photo true West Archives –

Phil Spangenberger has written for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.