From the Alaskan Arctic to the Bearpaw Battlefield in Montana, Charles Erskine Scott Wood was a man of action and adventure.

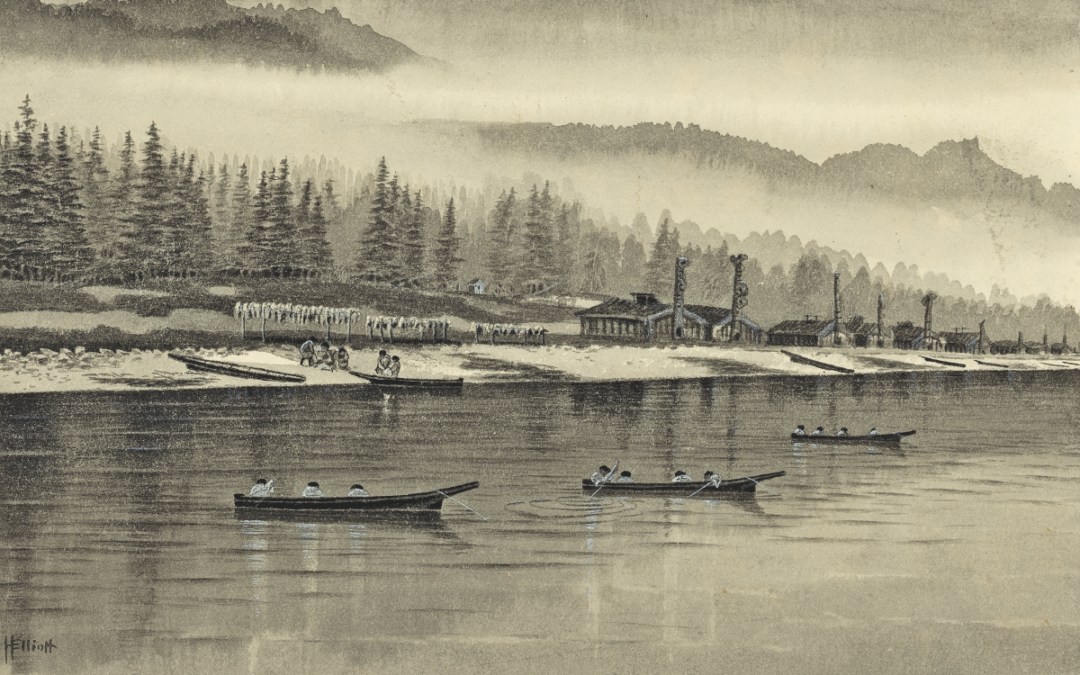

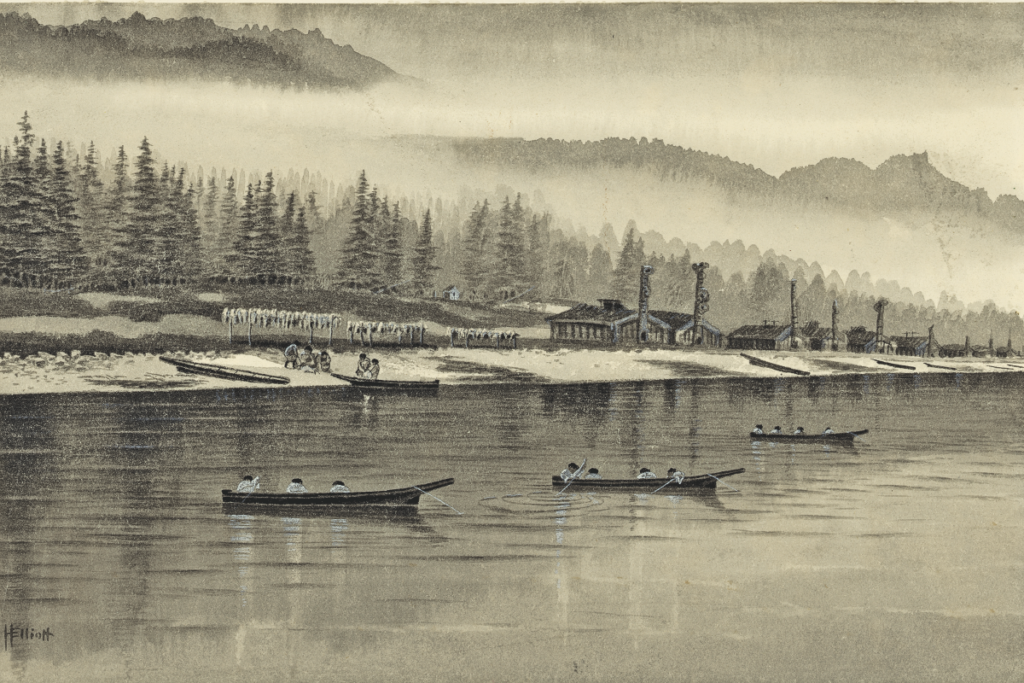

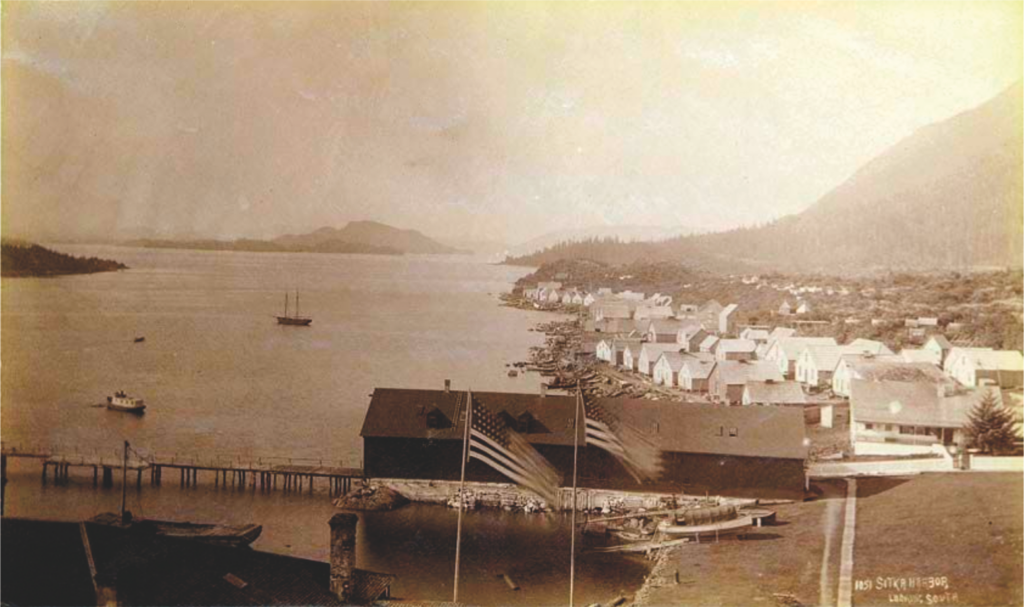

In the spring of 1877, Sitka, Alaska, was one of the most dangerous locations in America. The Russians had taken the town from Tlingit warriors after fierce, bloody fighting. That was in 1804. The Tlingits vowed to take back the port. Massed against the wooden stockade for generations, warriors would try to breach the walls to attempt to kill everyone inside. Neither the Russians, nor later the Americans, had the military might to clear out the large Tlingit village that had grown up around the wall. Sitka residents lived in constant fear that one day Tlingits would enter the city, not to trade but to kill.

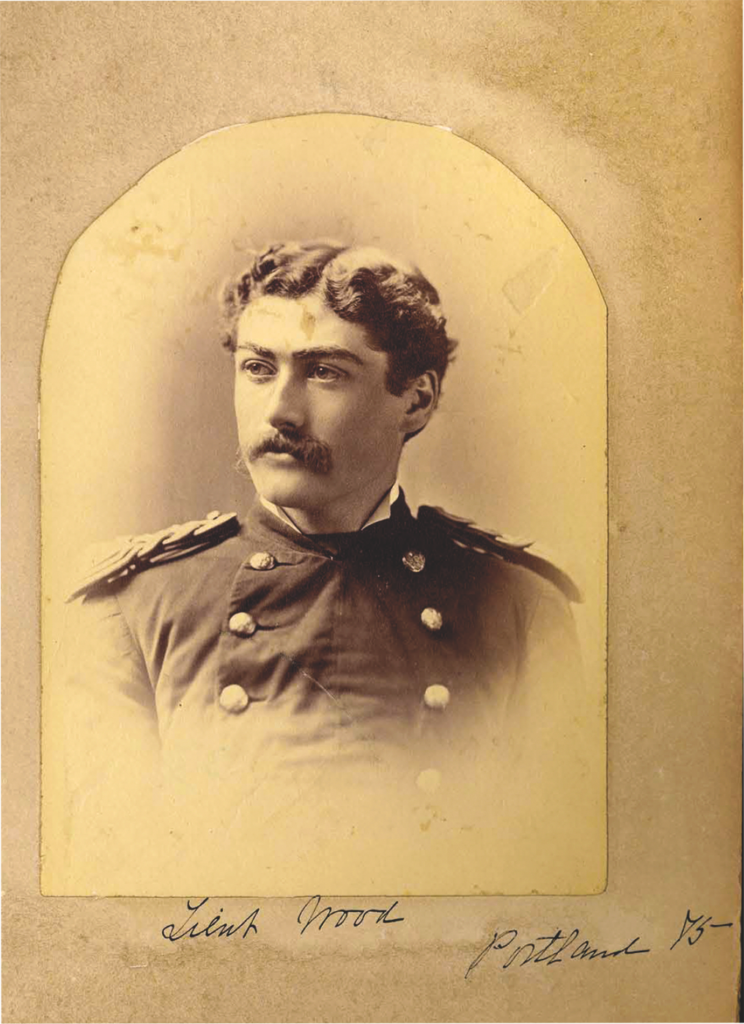

Sailing into this environment was Charles Erskine Scott Wood, a young, green Army lieutenant, with the man he was escorting, Chicago millionaire Charles Taylor. A noted mountaineer, Taylor had come to climb the highest mountain in North America, then thought to be Mount Saint Elias along the Alaska coast. For this adventure, he requested an Army escort.

Courtesy The University of Washington Digital Collections

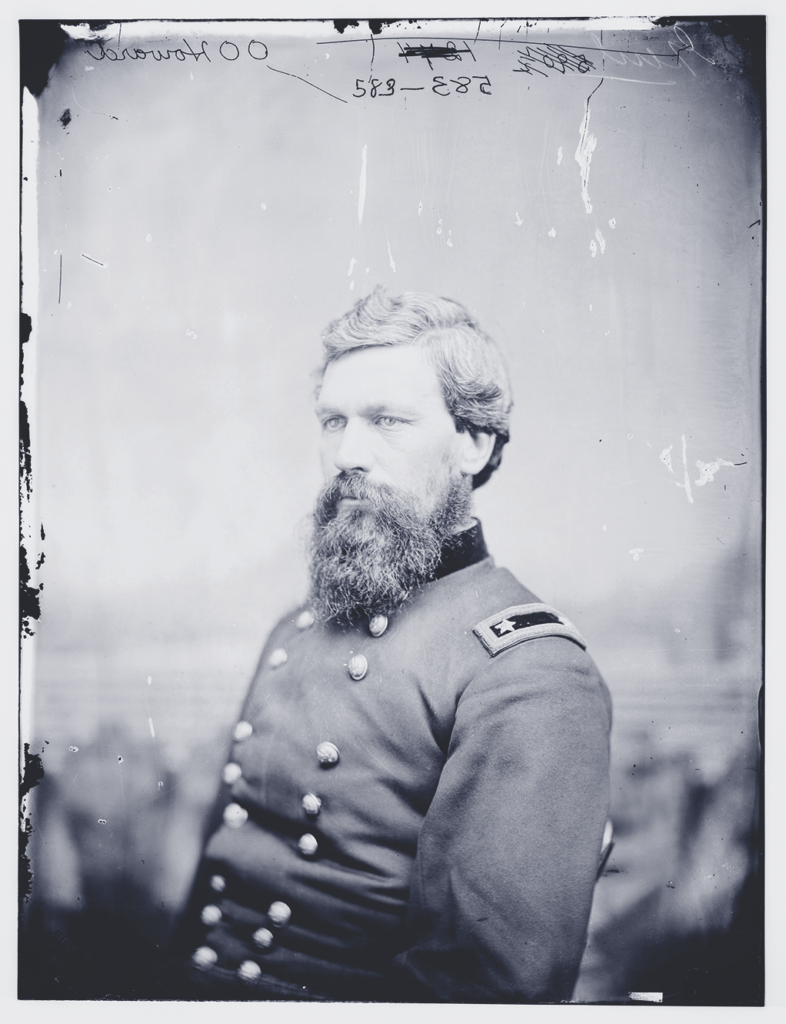

General Oliver O. Howard, commander of the Department of the Columbia, assigned Wood the task. A big man resembling a stuffed bear, Wood had been the darling of Washington society, a favorite among the ladies. He wrote poetry. His father, a career Navy man, pulled strings to get him into West Point, hoping it would make a man of him. When that seemed to fail, the elder Wood quietly arranged for his son’s transfer to the Wild West.

General Howard had no complaints about Charles Wood. He was punctual, well read and an excellent dinner conversationalist. But war clouds with tribes like the Nez Percé were gathering. Taylor’s project, however ridiculous, seemed perfect for toughening up the young Wood. Alaska was lawless—no sheriffs, no marshals. The 500 U.S. troops there were scattered in six outposts and afraid to go beyond their forts. The rest of Alaska was an enormous void with trappers and prospectors constantly disappearing.

Sitka’s pier was lined with “Indians, Russians, half-breeds, Jews, and solders,” wrote Wood as they disembarked in a cold April rain. The two men made their way past homes that had been well maintained during the Russian era but were now becoming dilapidated with the paint fading under American rule. In the center of town, Wood and Taylor passed the green dome and spires of the Russian Orthodox Church. Beyond the church was William Phillipson’s trading post. Inside, Tlingit trappers sold pelts shoulder to shoulder with American housewives buying items for home—salt, pepper and cloth. Phillipson had a trading schooner that sailed as far away as Kodiak. Taylor had written Phillipson about that schooner. He had planned to hire the craft to transport his expedition northward, but they had missed the sailing. Phillipson had waited for them, and when it seemed they were not going to arrive, sent the ship north. It would not be back for at least a month.

During the following days, the two men searched the small port for transportation. Then one day, there was a loud disturbance in the Sitka market. Soldiers were sent to restore order. A Russian trapper was trying to sell the silver-and-white pelt of a Saint Elias Bear or Ghost Bear. The pelt was rare and expensive. But it was also taboo among the Tlingits, a bad omen. They wanted the Russian to leave the market. Worse for Wood and Taylor, the trapper said he had taken the bear near Mount Saint Elias. It caused would-be Tlingit boatmen to think twice before agreeing to take the two Americans the same direction.

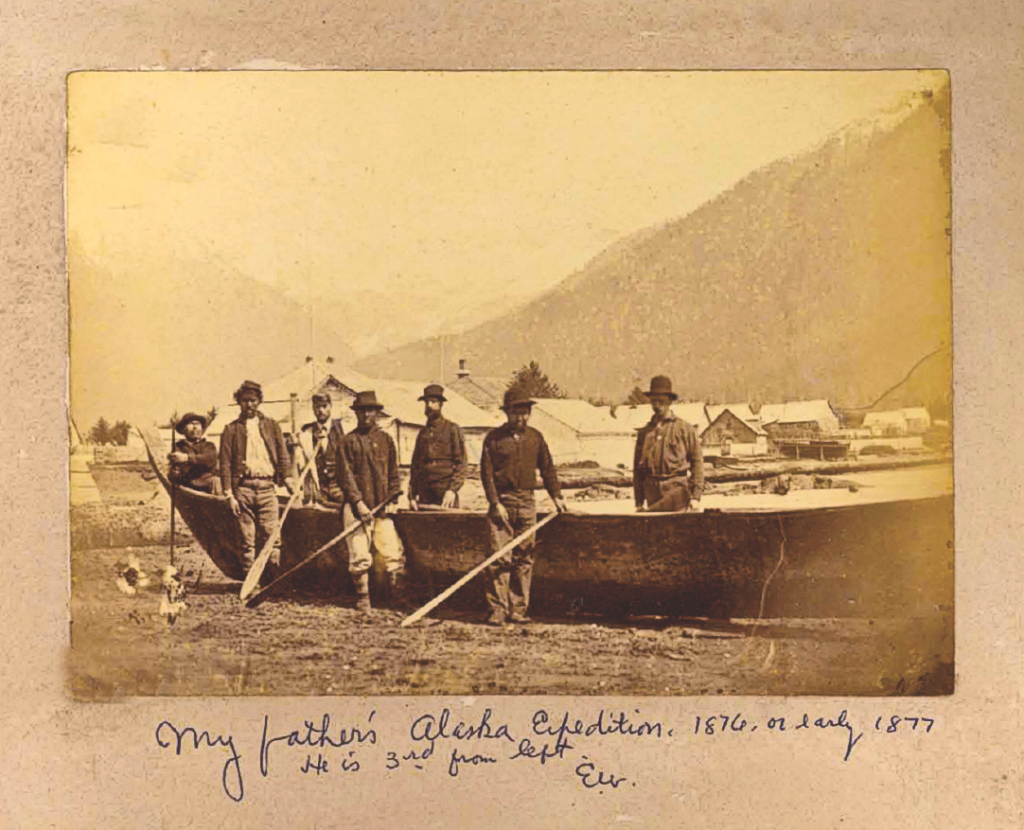

Finally, the two had to go outside the stockade into the Tlingit village to look for transport. It took Taylor a week to negotiate for a four-ton canoe with two Tlingits as crew and a Russian named Sam as an interpreter. The owner was hired as the pilot. An Army corporal and two privates were assigned to the expedition, and a Canadian prospector was hired as well. Once the expedition was approved by the Tlingit women of the long house the canoe belonged to, Taylor threw a ball and invited all of Sitka. The next morning, April 24, the canoe shoved off for the north.

Their route took them around small and large islands of Alaska’s Inside Passage, a waterway maze, but one that allowed them to avoid the open ocean for as long as possible. The twists and turns confused Wood, causing him to become lost and disoriented at times. After 11 days, they were forced to paddle the Pacific. Massive swells made them take shelter at a Chilkat native village. Its chief treated his guests to an endless seafood buffet. Afterwards they were handed the inner bark of a cedar, which when chewed, proved as sweet as candy.

At the village, Wood encountered his first native slaves. Captives from the interior, they ate and joked with their owners, but Wood observed they were the ones chopping wood and carrying water. The slaves could not marry without permission, and they could be sacrificed. Native slavery among American Indian tribes lasted in Alaska until the 1900s, while on the Great Plains it existed until the 1880s-90s, when intertribal warfare came to an end due to the presence of White society.

When the storm passed, the small expedition continued north, falling in with a party of Hoonahs on their way to harvest potatoes. The base of Mount Saint Elias was only five days away, the Hoonahs told them. Now the Tlingit paddlers refused to go any farther. Taylor threatened them, and Wood tried bribing them, but to no avail. The Tlingits had learned from the Hoonahs that a Ghost Bear had been sighted in that area.

“One mountain is as good as another,” one of the paddlers told the two men.

Taylor simply deflated. He asked Wood to take him back to Sitka. They arrived as a storm struck, delaying Taylor’s sailing to Sitka for nearly a week. It also gave Wood time to think. He did not want to return. Just before Taylor sailed out, Wood gave him a note to give General Howard. In the note, Wood explained he would return to the base of Mount Saint Elias and from there explore the Alaska interior, something no American had yet done.

Almost immediately Wood set off in the same canoe Taylor had hired. He stopped at the Chilkat village they had stopped at before to hire a few goat hunters to assist him when he reached Mount Saint Elias. They were traveling by way of Mount Fairweather. Less than a week later, as the party made its way into a wooded valley at the base of Fairweather, the Tlingits ahead of Wood froze in fear. Coming into the clearing ahead was a Ghost Bear. Not as large as a brown bear, the unusual creature was light blue and a silvery white. The animal crossed the clearing and then disappeared back into the forest.

The Tlingits would not move. “Nothing to do but turn back,” recorded a disgusted Wood. The party went overland to a Hoonah village along a massive bay choked with ice. The natives attached wooden false siding and a false prow to their canoes for travel through the icefields. The Hoonah chief told Wood that when he was a child, the bay did not exist. The area had been solid ice. Wood became the first White American to see Glacier Bay.

While Wood was staying in the Hoonah village, an old chief begged him to come to his village. The chief’s son had fallen ill. Wood went reluctantly. The Tlingits usually killed the doctor if the patient died. Finding the child feverish, Wood gave him a series of hot baths and soda powder as the villagers looked on. The doctoring worked, and soon Wood had a long list of patients, including an elderly man Wood felt would die soon. Despite the demands of his new profession, he found time for other activities.

The village chief had given Wood one of his young wives during a dinner party. He could not refuse, wrote Wood, especially because she grasped his hand and led him away to her bed. If he had refused her, it would have been an insult to the entire village. Living out of her bed kept him in the village for weeks longer than he had planned. The elderly man he was treating did not look well at all. Wood kept feeding him dried onions stewed in sugar, some cod liver oil and lots of alcohol.

He had arranged a canoe and told his new love and the chief he was just going to paddle around the bay and return. He had cache of supplies up the coast. His intention was to navigate the maze of islands of the Inside Passage back to Sitka.

Wood found Sitka in a panic. Howard had ordered U.S. troops to leave in preparation for war with the Nez Percé. No one would be left behind to protect the settlement from the Tlingits. (A British warship and its cannons eventually came to the town’s rescue.)

Wood boarded his homeward bound ship, but he was not completely satisfied. He had failed to climb or even reach Mount Saint Elias. But he had become the first White American to encounter a Ghost Bear and see Glacier Bay. He gave the first account of the Tlingits to the American public.

Lieutenant Wood left Alaska on June 11, 1877, joining Gen. O.O. Howard’s pursuit of Chief Joseph and the Nez Percé. On October 5, 1877, it was Wood who recorded Chief Joseph’s surrender speech, “From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”