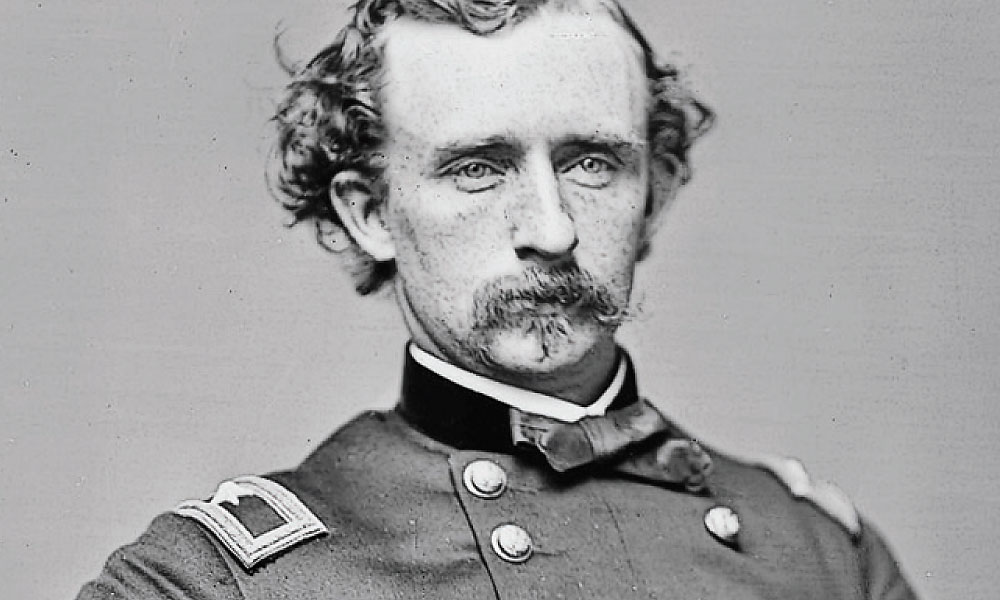

Allen Barra: You wrote in your preface, “Custer battled American Indians ruthlessly, yet wrote that he would resist too were he one of them.” His attitude reflects empathy toward Plains Indians, yet he has been reviled unmercifully by a modern generation of Indian writers, including Vine Deloria Jr., author of Custer Died for Your Sins, who called him the “Adolf Eichmann of the Plains.” Why did you take this stance?

T.J. Stiles: I try to understand Custer as a human being, in all his complexity and contradictions. The quote you cite does reflect empathy, but it comes from an essay in which he concluded that Indians were by nature savage, unable to become civilized. It was a pattern with him. As he did with African Americans, he often showed respect, even affection, for Indians on a personal level, but whenever he considered them on a political or intellectual level, he fell back into bigotry. Was this typical for a white American of his day? Certainly.

As for Deloria comparing him to Eichmann, that’s a deliberate provocation to draw our attention to the devastation of Native America. Custer never called for the extermination of American Indians and played no role in making federal policy or even military strategy. As a general rule, I refrain from equating other historical wrongs with the Holocaust. I think it pits victims against each other in a kind of atrocity sweepstakes.

Much of Custer’s negative press is due to his Washita Valley campaign. Was Custer’s performance at Washita vastly different than the U.S. Army’s treatment of the Plains Indians?

At the Washita, I believe that Custer’s actions were well within the contemporary standards of the frontier Army, but he cannot escape some moral culpability.

As Jerome A. Greene points out in his definitive study, the attack on a sleeping village at dawn was a classic frontier tactic. It emerged in response to a strategic dilemma: In a Plains Indian war, the Army had to seize control of an entire population that had a huge advantage in mobility, except in winter. An attack on a village both pinned down the fighting men and put the noncombatants directly in the Army’s power.

In terms of Custer’s personal guilt or innocence, I largely agree with Greene. In the assault, we have testimony that Custer sought to protect women and children. But he knew ahead of time that women and children would die in the attack. And he carried out [Maj. Gen. Philip] Sheridan’s order to bring no Cheyenne men back alive.

In any other setting, the Army would have considered both the order and its execution to be an atrocity, but the Washita was sadly typical in this setting; [Maj. Eugene A.] Carr’s assault on the Dog Soldiers’ camp at Summit Springs produced a similar death tally. That’s not a defense of such tactics, but it places Custer in context.

Custer’s critics have blamed him for the deaths of Maj. Joel Elliott and his detachment at Washita. Do you agree?

Chief scout Ben Clark said that Custer knew nothing of Elliott’s decision to ride off with a small detachment—though [Capt. Frederick] Benteen tried to get Clark to swear that Custer had ordered Elliott to go.

Elliott may have been killed before Custer even realized he was gone. Clark, who strikes me as fair-minded, concluded that Custer faced a real threat as warriors from the main camp surrounded the regiment. Stopping to conduct a major search could have endangered the entire command. Custer had valid concerns regarding the danger to his supply wagons, which he badly needed, his steadily shrinking ammunition reserves and the risk of remaining in place overnight.

Yes, he could have done more to search for Elliott, but not without risk, and I doubt he could have saved him. By contrast, I think Custer clearly deserves blame for abandoning two men on his infamous ride to [wife] Libbie in 1867.

One editor wrote, “General Custer wields the pen almost as skillfully as he does the sword.” Are Custer’s books worth reading today?

Worth reading? Definitely. The best reading? Much of the time, no, though some of it is quite rewarding. And, to pose the question I ask in the book, was Custer’s writing modern? Absolutely not.

Custer took writing seriously; Libbie dreamed that he might build a second career on it. Certainly, he could tell a good story. His account of the Washita is gripping, and his description of Wild Bill Hickok is terrific. He could place you in the saddle, as someone encountering the Great Plains for the first time in the 1860s.

But not all of it wears so well. Many of his articles for Turf, Field and Farm are about horses and racing, written for contemporary fans of the turf. In The Galaxy magazine, he revealed his ambition to be a public intellectual. His first two articles, which became the first two chapters of his memoir, My Life on the Plains, are a serious disquisition on the natural history of the Great Plains and a pseudo-scientific discussion of American Indians, influenced by the badly warped racial science of the day. These pages are mainly interesting to those who want to know how Custer thought.

You wrote, “A critical fact stands out: he captured the American imagination long before the Little Big Horn, even before he went west.” Yet to most Americans, Custer will always be regarded as a man of the West. What do you mean by, “He loved the West, but he was not of the West?”

I want to be clear: I am not debunking the idea that Custer was an important figure in the West. But he neither came from the frontier, nor did he commit himself to life there. He saw the West as an exotic place where he went on periodic deployments. He enjoyed the frontier and mastered it, in his mind, but in the end, he preferred civilization.

Libbie wrote that “life in the saddle on the free open plain is his legitimate existence,” claiming that he was relieved and happy to be transferred from Kentucky to Dakota Territory in 1873. But Custer wrote to her the same year, “What a delightful two years we have spent in the States.”

He especially loved New York and wrote of settling there after he made some money. He was a huge fan of the theatre, fine art and fine dining. To a certain extent, he was haunted by his origins as a small-town boy, born in the middle of nowhere to poor, badly educated parents. The glamour of Manhattan attracted him; he wanted the nation’s fanciest people to accept and admire him. In the end, that mattered more to him than his authentic love of the West and the outdoor life.

The 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn is what we remember best about Custer, but you don’t come down hard on him for his decisions in the campaign. As you put it, “Custer made a grave tactical error in dividing his force, exposing it to destruction in detail. It was fatal, but understandable.” Why understandable?

With the battle itself, several factors explain Custer’s actions. First, the precedent of the Hancock Expedition, when the Army column approached the Cheyenne and Oglala village on Pawnee Fork. No battle resulted, because the Indians were more concerned with helping their women and children to escape.

Second, the precedent of Washita, where Custer divided his force with great success. It was only the arrival of men from a separate village that led to the annihilation of Elliott’s detachment. For that reason, Custer expressed concern for catching all of the Indian camps and pushing them all together toward [Brig. Gen. Alfred] Terry and [Col. John] Gibbon’s column. He split off Benteen as a reconnaissance in force, to prevent a nasty surprise like in that second village at the Washita. He may have split off from [Maj. Marcus] Reno, both to strike the camp from two sides and to prevent anyone from escaping his attack.

Third, the size of the Little Big Horn village was extremely unusual. Such a vast assemblage led to a rapid depletion of grazing and pollution of the area through human and animal waste. Once supplies ran out, they had to split up to hunt. Sheridan knew this. He sent Terry a telegram to that effect on May 16: “I believe [your column] to be fully equal to all the Sioux which can be brought against it, and only hope they will hold fast to meet it…. You know the impossibility of any large number of Indians keeping together as a hostile body for even one week.”

I find it impossible to read that message and conclude that Custer defied orders or acted irrationally. Everything he did fit with Sheridan’s expectations and those of probably every other Army officer….

Besides, let’s give the Lakotas and Cheyennes full credit for their victory. As Robert Utley wrote, it’s less that Custer lost than the Indians won.

I’ve been dying to ask a Custer biographer this question for years: What do you think the future would have been like for him if he had won the Battle of the Little Big Horn?

Great question. His best choices were to make a career as a politician, financier, writer or celebrity.

Libbie stopped him from running for office, though he was a passionate conservative Democrat. The notion he planned to run for president in 1876 is nonsense. National Democratic politics were run from New York, as he well knew. I’ve looked at the papers of the Democratic kingmakers, including those of [Samuel J.] Tilden, who actually ran in 1876. They knew Custer personally, but never mentioned him in their political letters.

As a financier, he blew it. He didn’t pay enough attention to the actual operations of his mine, and he gambled disastrously on Wall Street, leaving Libbie a huge debt.

As a writer, he did much better, but never made enough to live on.

At the very end of his life, he did find a way to turn his celebrity into money. He planned to go on a lecture tour, which could have been quite lucrative, but how long could that have lasted? Even if he succeeded at public speaking, I suspect that Custer would have self-destructed, as he so often did, possibly by gambling with stocks or in a harebrained investment. In any event, he probably would have ended up about as well known to Americans today as Nelson Miles, Wesley Merritt or George Crook.

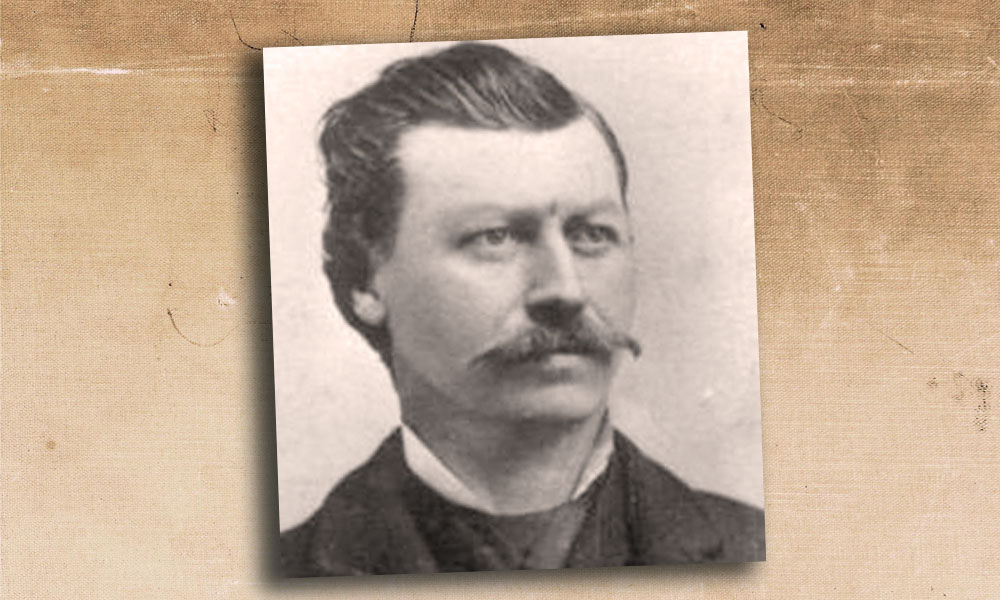

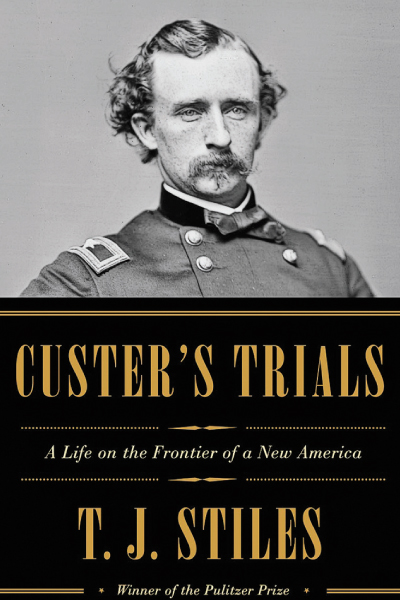

T.J. Stiles is the author of Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America (published in October 2015 by Knopf). He won the Pulitzer Prize for his Cornelius Vanderbilt biography, and he authored the 2002 biography, Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War.