— Courtesy Warner Bros., Eaves Movie Ranch —

Hollywood’s famous Chinese theatre celebrated L.Q. Jones’s 90th birthday with a screening of the controversial masterpiece that saddled Sam Peckinpah with the moniker “Bloody Sam,” 1969’s The Wild Bunch.

Jones roared with laughter when I told him the theme of my article for True West. “Peckinpah’s kinder, gentler side? Did he have one?” Then he quickly clarified, “It was a privilege to work with him. In spite of the stories I tell, I adored the man.”

Peckinpah had written nearly 50 Western TV episodes and directed over a dozen when MGM greenlit 1962’s Ride the High Country. The story of two aging, threadbare lawmen-gunfighters transporting gold from a mining camp, and inadvertently transporting a naïve would-be bride, would be the career capper for two great Western stars, Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott.

Jones had first met Peckinpah as Don Siegel’s dialogue coach on 1955’s An Annapolis Story. “Sam said, ‘Listen, kid, we’re going to be working together, because I’m going to be a director, and I’ll remember you.’ True to his word, once he got a little foothold, here came the calls, and we ended up doing, I think, 17 projects together,” Jones says.

— Lobby card Courtesy MGM —

For the role of runaway bride Elsa Knudsen, Peckinpah cast stage actress Mariette Hartley. “The very first thing I did was that wonderful movie,” she recalls fondly. Hartley wore a blue checkered dress to the audition, “And walking up those MGM steps, I felt like I was Alice in Wonderland. There he was, behind the desk, with his cowboy hat on and his feet on the desk with his cowboy boots on. They don’t do that in Connecticut. Sam read with me, that beautiful scene with Heck when I’m doing the dishes. He looked at me, and he said, ‘I think I’m in love with you.’ And Alice said to the Cheshire cat, ‘Thank you, I think.’”

For her screen test, Hartley says, “I wore a dress that was stuffed with a lot of stuff for breasts and Deborah Kerr’s wig from Quo Vadis. My hair was very short because I’d just finished doing Joan of Arc in Chicago. Two days after that [Producer] Phil Feldman called and told me I got the movie, and I about died.”

— Courtesy Warner Bros., Eaves Movie Ranch —

James Drury, who would soon gain fame as TV’s The Virginian, was wanna-be groom Billy Hammond, whose brothers figured Elsa would be bride to all of them. “Originally, Sam wanted Robert Culp for my part, and Culp’s agent said, ‘No, we don’t want Robert playing a bad guy,’ so he got me. I was able to play the part with great gusto, and I surely did enjoy that,” Drury remembers.

“We had John Davis Chandler, Warren Oates, L.Q. Jones, and John Anderson all playing my brothers,” he adds. “My God, you put that bunch of actors together—we were electric! It was truly a worthy group of bad guys to oppose Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott.”

Hartley agrees, saying, “Sam hired people the way John Ford hired people. He saw me as that girl—I was not a typical Hollywood beauty. I think he knew that I could be her, not play her.”

Eight years later, Peckinpah, who was finishing The Wild Bunch, called Jones about a script called The Ballad of Cable Hogue. “Sam was absolutely in love with it, but he had no money,” Jones says. “So he borrowed $17,000—all my money! Sam bought the project, sold it to Warner Bros. for a fortune, and never paid me back.”

For that 1970 Western, Jason Robards starred as Cable Hogue, a desert rat left to die by rivals who take his water. But instead of dying, he miraculously “found water where it wasn’t,” as he says in the movie, then builds a stagecoach stop and woos Hildy (Stella Stevens), the gorgeous soiled dove who must choose between love and wealth in San Francisco, California. Hogue’s spiritual advisor is a libidinous preacher played by David Warner.

“Hate that son-of-a-bitch!” says Jones, with a laugh. “I was supposed to be the preacher. But Sam was right; he did such a better job than I could have ever done.”

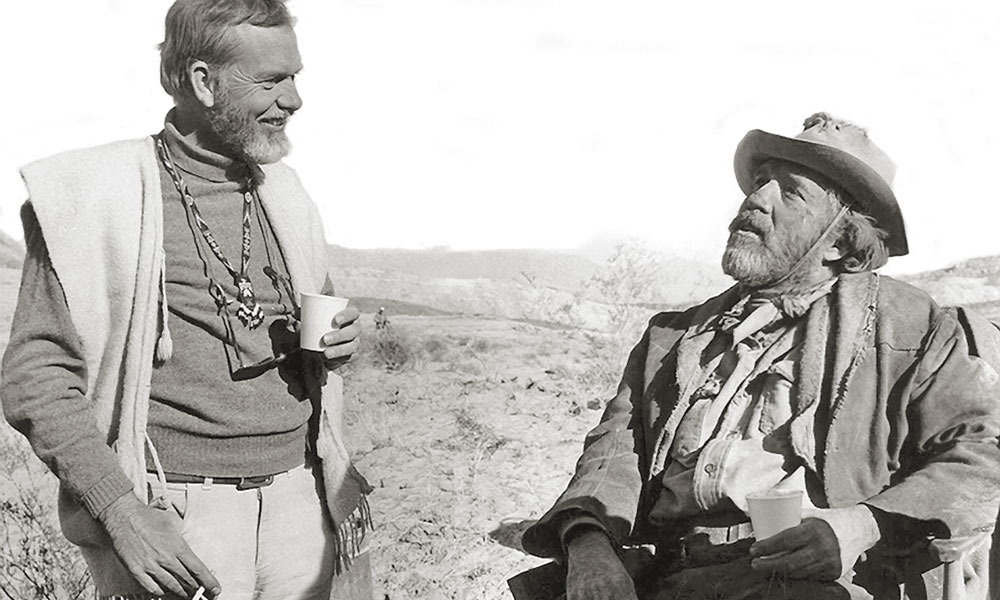

A newcomer in Peckinpah’s cast was Western novelist Max Evans. They had become friends after Peckinpah lost out on filming Evans’s The Rounders. For years, they tried to find a mutual project. In the film that finally joined them together, the stagecoach is prominent in the story, and Evans rode shotgun beside his close friend, driver Slim Pickens.

The Ballad of Cable Hogue was plagued with weather problems. “It rained 15 days, and we were jammed up in that hotel,” Evans recalls. “Then it turned hotter than Hell. It was 107 to 110 degrees where we were shooting.”

A quirky mix of slapstick and sentiment, the Western was viewed by Peckinpah as a comedy, but Stevens insists it is a love story. It’s also her best work, and maybe Robards’ as well.

At the time the film was made, “Jason Robards was down; he was a drunk. Had a bad reputation,” Evans recalls. “Sam took him, got him to quit drinking and made a great actor out of him. Jason went on to win two Oscars and an Emmy after Sam got him straightened out.”

Neither of these Peckinpah films were nominated for any major awards, but their reputations grow with each passing year.

Henry C. Parke is a screenwriter based in Los Angeles, California, who blogs about Western movies, TV, radio and print news: HenrysWesternRoundup.Blogspot.com