— Courtesy University of Cincinnati Libraries Digital Collections —

December 1831, central Texas saw an epic gunfight—with more than 170 combatants!

“Epic” and “Bowie” usually come together when describing the 13-day struggle for Texas independence at the Alamo that killed pretty much all of the defenders.

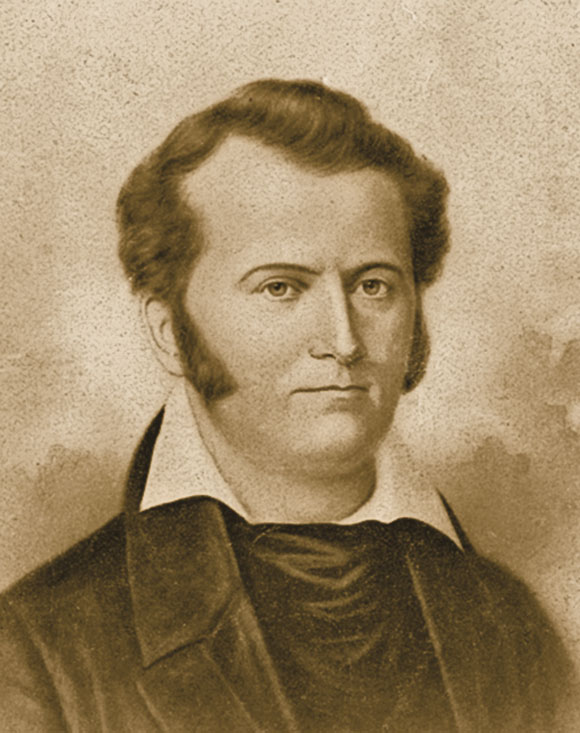

For now, though, one of those men, Jim Bowie, was roughly five years away from that fate and was instead well known for his knife duels, fought with his trademark Bowie knife.

Yet Jim was not the only belligerent Bowie brother.

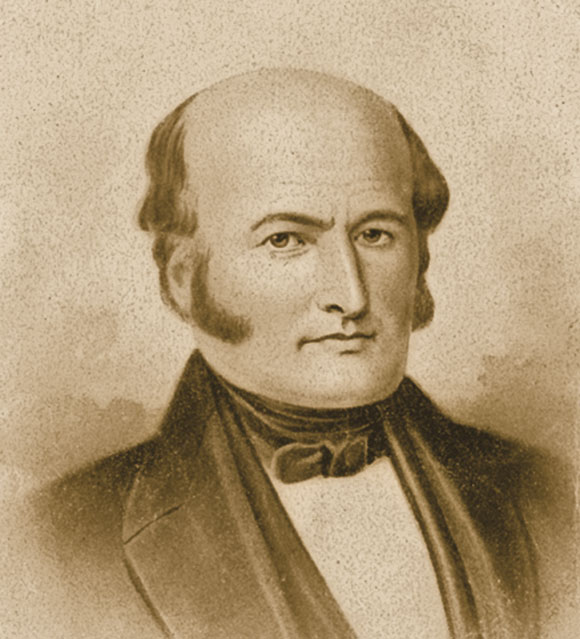

Rezin brought aggression and hostility full force during an expedition to find a rumored lost Spanish silver mine with younger brother Jim and their party, when they found themselves confronting more than 160 American Indian warriors, who were not happy to see strangers invading their homeland.

— Courtesy Prints and Photographs Collection, Texas State Library and Archives Commission —

Their raging, day-long battle would become a testament to the warriors’ tenacious determination to protect their territory and to the treasure hunters’ wherewithal to defend themselves against the overwhelming odds of 15 to one.

The Bowie brothers never found the silver, but the legend of the Lost San Saba Mine fed the imagination of treasure hunters for years to come.

Courage Under Fire

On December 2, 1831, Rezin, Jim and nine others left San Antonio. They received a warning on December 19; they were being followed by 124 Tehuacana and Waco warriors, and 40 Caddos.

— Courtesy Prints and Photographs Collection, Texas State Library and Archives Commission —

The Bowie party picked up the pace. The men hoped to reach the ruins of Presidio San Saba that night. But the rocky roads were wearing out the feet of their horses, and they had to stop about 12 miles from the Spanish fort.

Seeking a location that could be well defended, they spotted a grove of about 40 live oak trees. To the north of the trees was a thicket of live oak bushes about 10 feet high, 40 feet long and 20 feet wide. Inside the thicket, about 10 feet from the outer edge, the men cut a wide path, clearing any prickly pear cactus. Forty yards to the west was Calf Creek. Hobbling their horses and placing guards on watch, the party retired for the night.

The next morning, while saddling up to depart, they noticed a war party about 200 yards to the east: 164 braves against 11 members of the Bowie group.

Scrambling back to their defensive positions amongst the oak trees, the Bowie brothers and their men tied their horses. Rezin and David Buchanan decided they would negotiate, hoping to avoid a confrontation.

About 40 yards from the war party, Rezin requested that the tribes send out their leader to talk. The warriors responded by discharging 12 shots, one of which broke Buchanan’s leg.

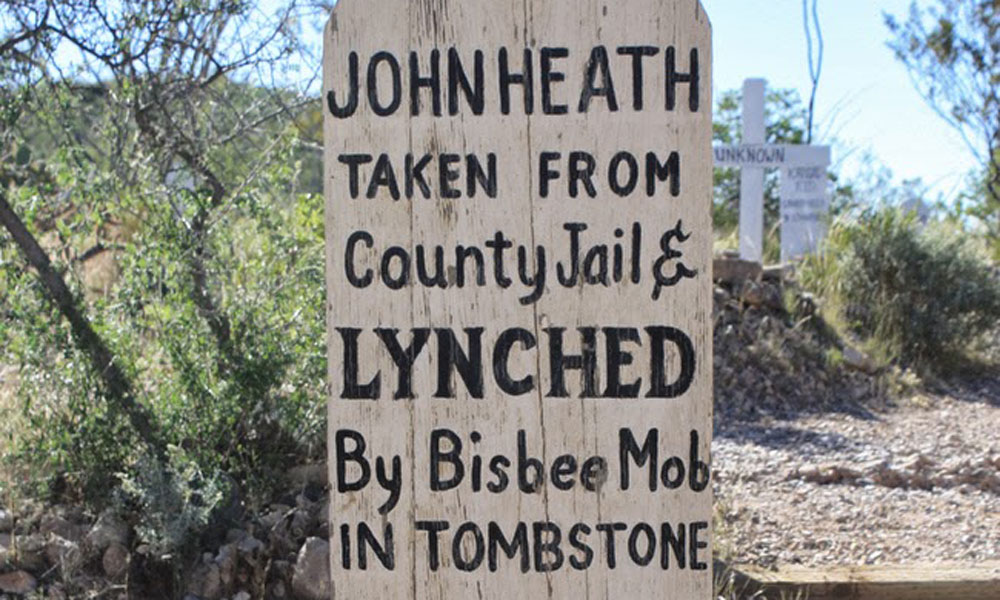

— True West Archives —

Rezin returned fire with a double-barreled shotgun and a pistol. When he saw an opportunity, he ran to Buchanan, threw him over his shoulder and carried him back to the encampment.

The Indians fired a volley that struck Buchanan again, this time in two other places. The bullets also pierced the hunting shirt of his savior, Rezin, but fortunately did not injure him.

Seeing Rezin unharmed, eight warriors took after him on foot. Rezin’s comrades stepped in, shooting down four of the braves. The remaining four retreated.

On a hill about 60 yards to the northeast, warriors yelled and then opened heavy fire on the defenders. A chief on horseback loudly urged his men to charge the thicket.

Caiaphas Ham shot at the chief, which broke the chief’s leg and killed his horse. Four others in the Bowie group loaded and shot at the chief all at once, immediately killing him.

Struck this deathly blow, the warriors surrounded their chief and carried his body away. Several fell dead as the Bowie crew continued shooting. The rest of the braves retreated over the hill and out of gunshot range.

A surprise was coming.

— JN Marchand Illustration published in Munsey’s Magazine, December 1901 —

The Telltale Thicket

Approximately 20 Caddos had found cover behind the bank of Calf Creek, about 40 yards to the rear of the defenders.

The Caddos opened fire, shooting Matthew Doyle. The ball entered his left breast and exited out his back.

Thomas McCaslin ran to the badly wounded Doyle, thunderously yelling, “Where is the one that shot Doyle?”

His comrades told him to get out of there, but McCaslin raised his rifle and aimed it at a Caddo rifleman.

Bam! McCaslin, not the Caddo, got shot through the center of his body. He died immediately.

Robert Armstrong raised his gun at another Caddo. A rifle ball from the enemy cut off a portion of the stock of his gun and lodged against the barrel.

The defenders were completely surrounded. The war party had positioned themselves on high rocks and behind trees, firing on the men from all sides.

Exposed to this heavy fire, the defenders scrambled from the oak trees into the brush thicket pathway they had cleared the night before. From this position, the brush hid them, and they had the advantage of being able to see their attackers.

The defenders fired at the warriors through brush openings and then scurried farther inside the thicket to avoid return volleys. The only telltale sign of where the warriors should shoot into the thicket was the gun smoke billowing out of the bushes.

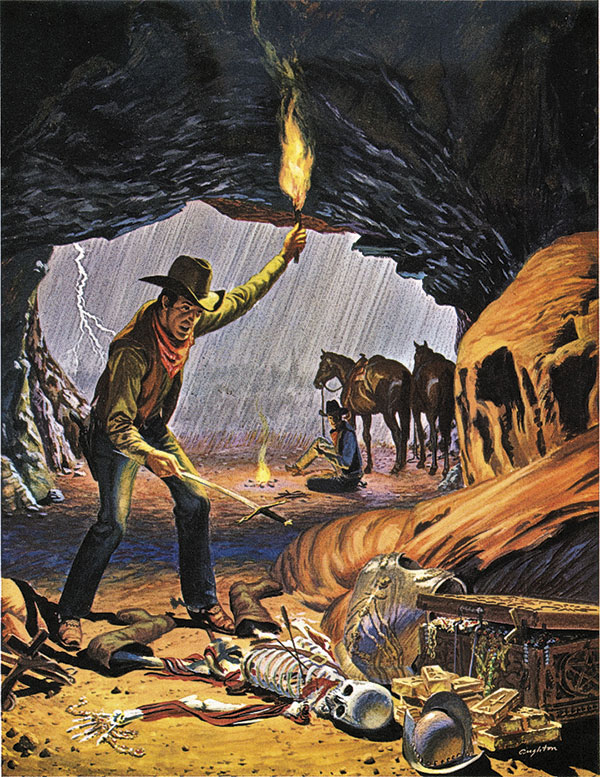

— Illustrated by Taylor Oughton —

A Fire Prison

The ferocious battle continued for the next two hours.

Every volley from the Bowie group was taking down about six warriors. They were gaining ground.

The warriors shifted tactics. They set fire to the dry grasses primarily so they could dislodge the Bowie group, although the thick smoke also provided cover as the warriors carried off their dead and wounded.

The Bowie party hastily scraped away the dry grass and leaves near their own wounded so that the fire would not burn there. They built a breastwork out of rocks.

Seeing that the flames did not route the defenders, the warriors again took positions on high rocks and behind trees, and started firing upon the Bowie group with renewed vigor.

The wind shifted and blew hard from the north. If the war party could set fire to the remaining small area of grass around the defenders, the wind would push the flames directly toward the thicket.

One warrior crawled along the creek and succeeded in lighting that area of grass. But he paid with his life when Armstrong shot him dead.

Seeing that the 10-foot-high flames would soon reach the barricaded men, the attackers yelled encouragingly and increased their rate of fire to about 20 shots per minute. They watched as the flames reached the breastwork around the Bowie party.

From the temporary fortification, the able-bodied men grabbed their buffalo robes, deerskins and blankets to smother the flames. A momentary success. The fire burned around them and passed by.

With the thicket now burned and providing no cover, the men hunkered down inside the breastwork.

The battle had raged since sunrise, and it was now sundown. The fighting paused. The warriors set up camp about 300 yards away, tending to their wounded and mourning their dead.

Under cover of darkness, at the creek, the defenders filled their vessels and skins with water. They anticipated an attack in the morning.

Bloodied Grass

At daylight, the braves moved their dead to a mountain cave about a mile distant and then left the area.

Two of the Bowie party stealthily left the fortification and went to the warrior camp. They counted 48 bloody spots in the grass versus one man killed and three wounded from their side.

Around one p.m., 13 warriors arrived. Once they saw the men in the barricade, ready to fight, they turned around and left. Was the ferocious battle finally over?

The Bowie brothers and their group remained in their fortification for several more days, taking care of the wounded. They eventually left at night, stopping along the way for two days to prepare for another attack and to apply a poultice to Buchanan’s badly infected leg.

Ten days after leaving Calf Creek, they arrived in San Antonio, battered and without silver riches to boast, but feeling lucky to be alive. Rezin had survived the major battle he would fight in his life, although he lived only five more years after Mexican troops killed Jim at the Alamo. His San Saba heroics marked him braver than the average land speculator.

Tim Dasso is a freelance writer in central Texas, where he observes Texas historical sites and researches historical events. He is writing a historical fiction based on events that occurred in Texas’s early years.