Tourists that spend their money to see rocks and falls are fools,” a shepherd told John Muir in 1869 during Muir’s fabled First Summer in the Sierra.

Since I like rocks and waterfalls, and have often been called a fool, I don’t believe such a statement. I can’t help but wonder though what John Muir would think about our national parks today. Not so much the parks, but the tourists. I pull off the road to let some malcontent speed by me.

“Hey, pal!” I mutter under my breath while saluting him with a finger. “This is Yosemite National Park—not the 405 in LA!”

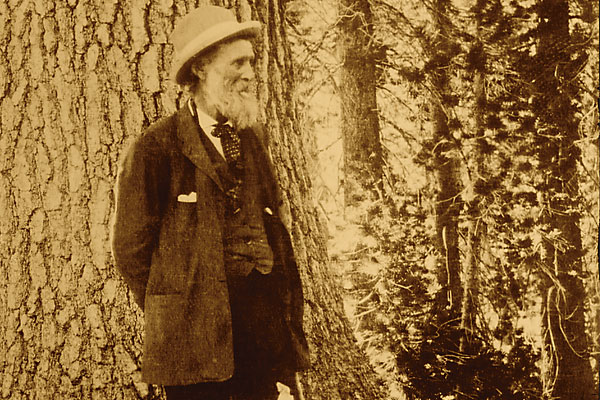

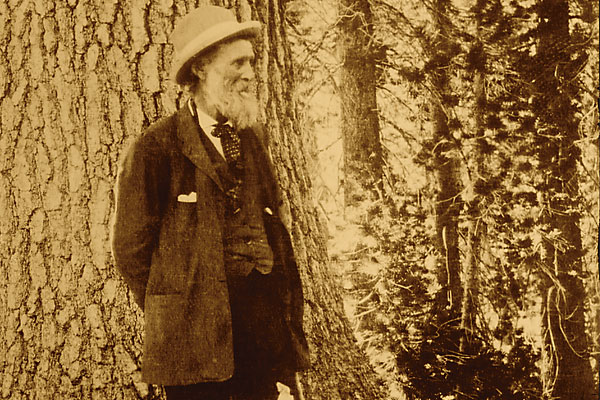

I’m following the trail of John Muir (1838-1914), the “Father of our National Parks,” the “Wilderness Prophet,” the “Citizen of the Universe,” the “Magnificent Tramp,” America’s foremost naturalist, preservationist and conservationist, or, as he described himself: “poetico-trampo-geologist-botanist and ornithologist-naturalist, etc. etc.”

The Natural

Born in Scotland, Muir came to America in 1849 when his family started a farm in Wisconsin. Muir likely would have been lost to history as a victim of the industrial revolution, an inventor and clockmaker, if not for a factory accident on March 6, 1867, that almost cost him his right eye. As he recovered, he did some serious soul-searching. “I might have become a millionaire,” he said, “but I chose to become a tramp.” For this, America is eternally grateful.

His trampings would take him across the continent, walking to the Gulf of Mexico, traipsing across California’s High Sierra and canoeing into Alaska’s Glacier Bay. At Yellowstone, the Great Basin, the Petrified Forest, Mount Rainier and many other places in the wild, Muir would leave his mark, and in many cases his name, on some of the most breathtaking places America has to offer.

As Rod Miller writes in his entertaining biography, John Muir: Magnificent Tramp, “In his love for nature and his efforts to protect it, Muir was very much a man of his time—indeed, a man ahead of his time.”

Home is Where…

The best starting point on any John Muir trail is his home in Martinez, California. The John Muir National Historic Site preserves the 14-room Victorian house and—as Muir would have insisted—its fruit orchards and 326 acres of woods. The informative video, John Muir: Earth, Planet, Universe, provides an overview of Muir’s life and legacy, and the Muir House brings Muir the man and the Victorian age into sharp focus. Muir’s in-laws originally built the mansion in 1883, but Muir and his wife moved into the house in 1890. Muir would live there, and write there, until his death in 1914.

Naturally, you can’t really appreciate John Muir indoors, so it’s time to take a walk.

“Going to the woods is going home,” he wrote, “for I suppose we came from the woods originally.”

Just down the road in Mill Valley, Muir Woods National Monument—“the best tree-lovers monument that could possibly be found in all the forests of the world”—celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. Part of Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Muir Woods offers six miles of trails where hikers, which there are plenty of, can view redwoods and a diverse array of flora and fauna. You don’t have to be a tree-hugger to appreciate the dignity and beauty of these woods.

Riding the High Country

Muir is most connected to California’s Sierra, so I leave the Bay Area for the high mountains and make my way west.

Malcontent motorists notwithstanding, it’s easy to forget idiotic drivers once you take in all the nobleness of Yosemite National Park. Muir led the fight to protect the area, resulting in the creation of the national park in 1890. Subsequent lobbying and preservation efforts—including a losing effort to stop the Hetch Hetchy dam—led to the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916, to protect and preserve all national parks and, according to its mission statement, “leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

A friend of mine takes Muir’s writings with him whenever he hikes in Yosemite’s back country, so I’ve likewise armed myself for this road trip. A mighty good idea, because Cathedral Peak does display “Nature’s best masonry and sermons in stones,” the canyon cliffs are “majestic” and California might still be “the floweriest part of the continent.” Yosemite is a garden—almost 1,200 square miles—of meadows and waterfalls, valleys and sequoias.

It was here at Glacier Point, a park ranger jokes on an early evening tour, that two American presidents were caught sleeping together. In a tent, of course. They were Teddy Roosevelt, president of the U.S. of A., and John Muir, president of the Sierra Club, which Muir founded in 1892.

Teddy described Yosemite as “bully.”

Big Trees, Deep Canyon

Muir also found refuge and wonder among the giant sequoias in the Southern Sierra, where he first visited in 1873, exploring the vast groves of “big trees” and the stunning vistas of Kings Canyon.

Buffalo soldiers of the Ninth Cavalry, under command of Capt. Charles Young, completed the first road into Sequoia National Park’s “Giant Forest” in 1903.

When loggers threatened the survival of the “big trees,” Muir noted mankind would “sell the rain clouds and the snow and the rivers to be cut up and carried away, if that were possible.”

Originally set aside as General Grant National Park in 1890—today covering a small portion of what is now Kings Canyon National Park—Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Parks comprise 863,700 breathtaking acres, much of that being back-country wilderness.

“Every tree of all the mighty host seemed perfect in beauty and strength,” wrote Muir, “and their majestic domed heads, rising above one another on the mountain slope, were most imposingly displayed, like a range of bossy upswelling cumulus clouds on a calm sky.”

Climb Every Mountain

Muir didn’t just enjoy California’s natural wonders. In 1888, he set out with artist William Keith to climb Washington’s Mount Rainier—all 14,410 feet of it—on one “fine sunny day, with glorious views of Rainier.”

I’m jealous. It took me three trips to Seattle before I ever saw Mount Rainier. The other times, I spied nothing but

rain clouds.

To Muir, and most tourists, the Cascade Range is as impressive as the Sierra, bringing in approximately two million visitors each year, many of whom don’t drive like malcontents.

“Every leaf seems to speak,” Muir wrote. “One gets close to nature, and the love of beauty grows as it cannot in the distractions of a camp.”

Mount Rainier was designated a national park in 1899.

Old and Faithful

Muir was a fan of Yellowstone National Park, which he visited in 1885, some 13 years after it had been designated as America’s first national park. “Unnumbered lakes shine in it,” he wrote, “united by a famous band of streams that rush up out of hot lava beds, or fall from the frosty peaks in channels rocky and bare, mossy and bosky, to the main rivers, singing cheerily on through every difficulty, cunningly dividing and finding their way east and west to the far-off seas.”

The thing I like most about Yellowstone—well, I mean, next to the wolves and the bears and the bison and John Colter stories and Nez Perce stories and Old Faithful and the great falls and the moose and the trout—is the fact that no one drives like a malcontent. They hardly drive at all, pulling off road after road after road to watch the wildlife.

Desert Solitaire

Muir also set out for 13,063-foot Mount Wheeler, now located in Nevada’s Great Basin National Park, checking out that country and those ancient bristlecone pine trees in 1877 and 1878.

Established as a national park in 1986, Great Basin is probably the least known park we have, perhaps because most people picture Nevada as a giant wasteland. Yet Muir found “falling water, cloud drapery, thunder tones, lightning, and blue sky windows.”

The desert offered much to love and preserve, and Muir eventually found himself with Gifford Pinchot in 1896 at the Grand Canyon—“Reds, grays, ashy greens of varied limestones and sandstones, lavender, and tones nameless and numberless”—and in 1905, at the Petrified Forest, “a kaleidoscope fashioned by God’s hand.” The Petrified Forest gained national monument designation in 1906; as did the Grand Canyon in 1908.

The Road Goes On Forever

The road of John Muir ended on Christmas Eve, 1914, when he died from complications of double pneumonia in a Los Angeles hospital. Today, LA’s urban sprawl seems an unfitting place for Muir’s life to pass, but even with its truly malcontent drivers, the City of Angels pays tribute to our favorite tramp. It is home to the John Muir Branch Library, John Muir Middle School, John Muir Outpatient Center….

Across California, indeed across the West, you’ll find John Muir’s name, from urban centers—John Muir Charter School, John Muir Center for Regional Studies—to deep inside our national parks—Muir Glacier, Muir Inlet, Muir Rock, Muir Grove, Muir Hut, John Muir Trail, Mount Muir, Camp Muir….

When I started researching this article, an early thought was to ask biographer Rod Miller and maybe a Sierra Club representative to pick a national park today that John Muir had never visited but would truly have loved. Yet early on, while I was walking with my son through Muir Woods, I realized that idea was silly. John Muir would have loved them all, and he would have known they would, and must, endure.

“It is always sunrise somewhere; the dew is never all dried at once; a shower is forever falling; vapor is ever rising. Eternal sunrise, eternal sunset, eternal dawn and gloaming, on sea and continents and islands, each in its turn, as the round earth rolls.”

Johnny D. Boggs’s favorite national parks are Glacier, Big Bend and Great Smoky Mountains.