In 1906, just three years after the 12-minute The Great Train Robbery, the first ever hour-long film, The Story of the Kelly Gang, another Western, was made not in the U.S., but in Australia. And before you say, “That doesn’t count as a Western,” consider this: it’s set in the 1870s, in a pioneering region usurped by white settlers from indigenous people, during a gold rush, and it’s about a gang of stagecoach robbers, although there, they’re called bushrangers. If that’s not a Western, then neither is Stagecoach.

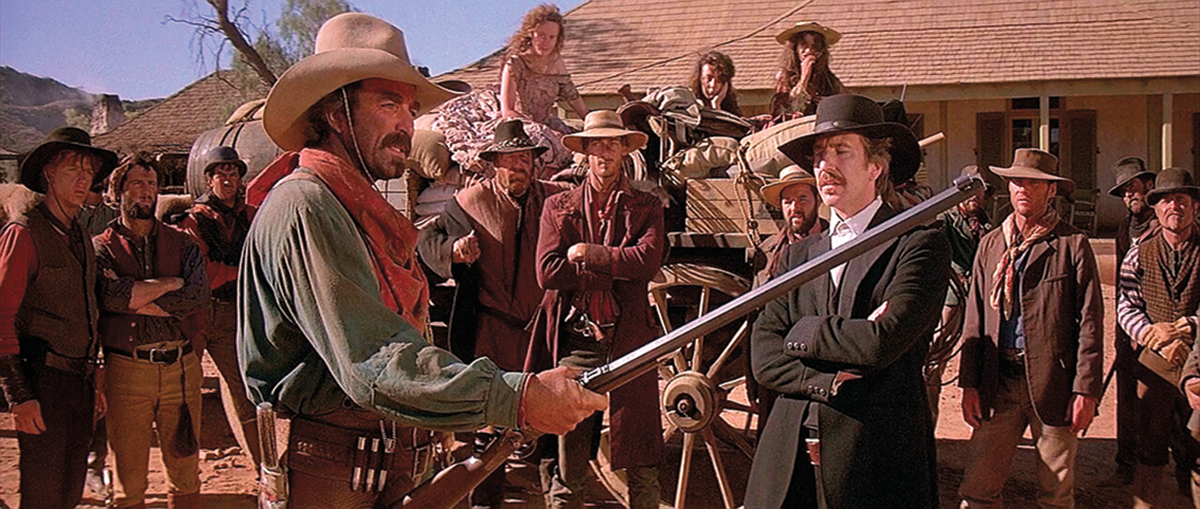

Both Australia and America have a fond- ness for tales of pioneering, individualism and daring. We see in Paul Hogan as Crocodile Dundee a shared exuberance and confidence. And that personality extends to the filmmakers as well as the films. Actress Laura San Giacomo fondly recalls going to Australia to star in Quigley Down Under, and meeting the crew. “There was a very gung-ho, cavalier spirit of filmmaking, [as if] it was going to be very easy to do this Western, to do a really difficult shoot.”

Ned Kelly and the Bushrangers

Australians also share our fondness for legendary “bad boys.” We have our Jesse James and Billy the Kid; they have their bushrangers: Ben Hall, “Mad Dog” Morgan and Ned Kelly. For good guys, we’ve got Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson. And the Australians? “We don’t have anyone like that,” explains Simon Wincer, the Australian director of Lonesome Dove and Quigley Down Under. “The police were nearly all Irish, often pursuing their own, as in the case of Ned Kelly, who was Irish heritage. So the ‘traps,’ as they were known, were not liked.”

And with good reason: while the settlers of the American West were there by choice, Great Britain expelled 164,000 English and Irish criminals and rebels to Australia. The bushrangers, particularly Ned Kelly, who famously beat plow shears into armor, are admired not for their robberies but for their opposition to the government. Legend of Ben Hall director Matthew Holmes explains, “The public cared for [them] because they knew what it was like to be oppressed by the British police. They also cared because the gang would pay them to provide shelter and information.”

There are probably more biographical films about Ned Kelly than any other Australian.

– COURTESY J. AND N. TAIT/ JOHNSON AND GIBSON PRODUCTIONS –

The best of them, Tony Richardson’s Ned Kelly (1970), features an unexpectedly strong and moving performance in the title role by Mick Jagger, who also sings the Irish/Australian rebel ballad, “There Was a Wild Colonial Boy.” Notes Wincer, “[Its screenwriter] Ian Jones was the foremost authority on Ned Kelly. Ian created a television series called The Last Outlaw, that’s probably the closest to being accurate.”

Australian Heath Ledger played Kelly to great acclaim in 2003’s Ned Kelly, with fellow Australians Gregor Jordan directing and Geoffrey Rush costarring. Most recently, 2019’s True History of the Kelly Gang is at its most interesting in Ned’s early years, when bushranger Harry Power (New Zealander Russell Crowe) shows him the ropes of crimi- nality. Wincer says, “I hated [it]. It was a whole revisionist look at Ned, and I didn’t like it at all. It’s just what I call a wank.”

Dan Morgan’s behavior marked him as psychotic even among bushrangers, so writer/director Philippe Mora was indeed fortunate to hire Easy Rider’s Dennis Hopper to play him, with Aboriginal star David Gumpilil (Walkabout) as his sidekick. Mad Dog Morgan is surprisingly watchable. It’s even more surprising that it was completed. Hopper recalled that fueled by cocaine and rum, he crashed a truck through a cemetery, and the Victoria Police, rather than jailing him, drove him directly to the airport and put him on a plane for the U.S., with the shooting unfinished.

– IMAGE AND POSTER COURTESY 20TH CENTURY FOX –

“Ben Hall was a successful landowner and cattleman,” notes Holmes. “He had no criminal record until his life fell apart—his wife ran away with his friend and took their young son.” The Legend of Ben Hall (2017) is a remarkably well-told story of Hall’s attempts to do right by his son, and to steal enough to finance a move to the States. Star Jack Martin is the spitting image of Hall, and a fine actor. “Ben Hall was made by a couple of young guys, literally on the smell of an oily rag,” says Wincer. “They did a great job with the money they had.

“The Proposition, with Guy Pearce and Ray Winstone, was a very good movie. Gosh, it was bleak.” Bleak indeed, the 2005 film is a Western noir. Outlaws Pearce and his kid brother are arrested by Police Captain Winstone, who makes a proposition: he will hang the kid brother on Christmas unless Pearce kills their much more dangerous older brother, played by Danny Huston.

Banjo Paterson and Snowy River

Beloved for Waltzing Matilda, Banjo Paterson is also famous for his poem, “The Man from Snowy River.” Written 130 years ago, it’s about the chase to recapture an escaped horse, and just as much about social class and prejudice. The 1982 film was directed by George Miller. Its executive producer Simon Wincer recalls, “We had the poem, which is a great finale for a movie. But we had to invent the first 90 minutes before we got to what we call ‘the ride.’” They wisely interwove a romance, involving the poor but honest protagonist, and the headstrong, beautiful daughter of Harrison, the wealthy landowner. Miller cast the stunning Sigrid Thornton, whom he’d directed as Ned Kelly’s sister in The Last Outlaw. The “man” was young Tom Burlinson, and when Kirk Douglas was offered the role of Harrison, he agreed, provided he could also play Harrison’s brother, Spur. The classic adventure spawned a sequel and a series.

Family Fare

In 1947’s wonderful A Bush Christmas, five children befriend a trio of campers, led by Chips Rafferty, not realizing that they are rustlers, until Dad’s valuable horse disap- pears. The five friends strike out to recover the horse, with unexpected results. Reflecting attitudes similar to the Our Gang comedies, the film features one Aboriginal boy, but race never enters into anyone’s thinking. In 1958, 25 years before A Christmas Story, the Australian film Smiley Gets a Gun tells the story of a 10-year-old who wants the .22 rifle of policeman Chips Rafferty as much as Ralphie wants the Red Ryder BB-gun, and tries everything to earn it.

Quigley Down Under

Before Quigley, Wincer directed films about horse-racing like Phar Lap, and cavalry pictures like The Lighthorsemen. “I learned to ride when I was about four years of age and that was a passion that has never left me. I’m in my seventies now and still riding. Because of my interest in horses, and knowing what you can and can’t do with them, people kept coming back to me to make more Westerns.”

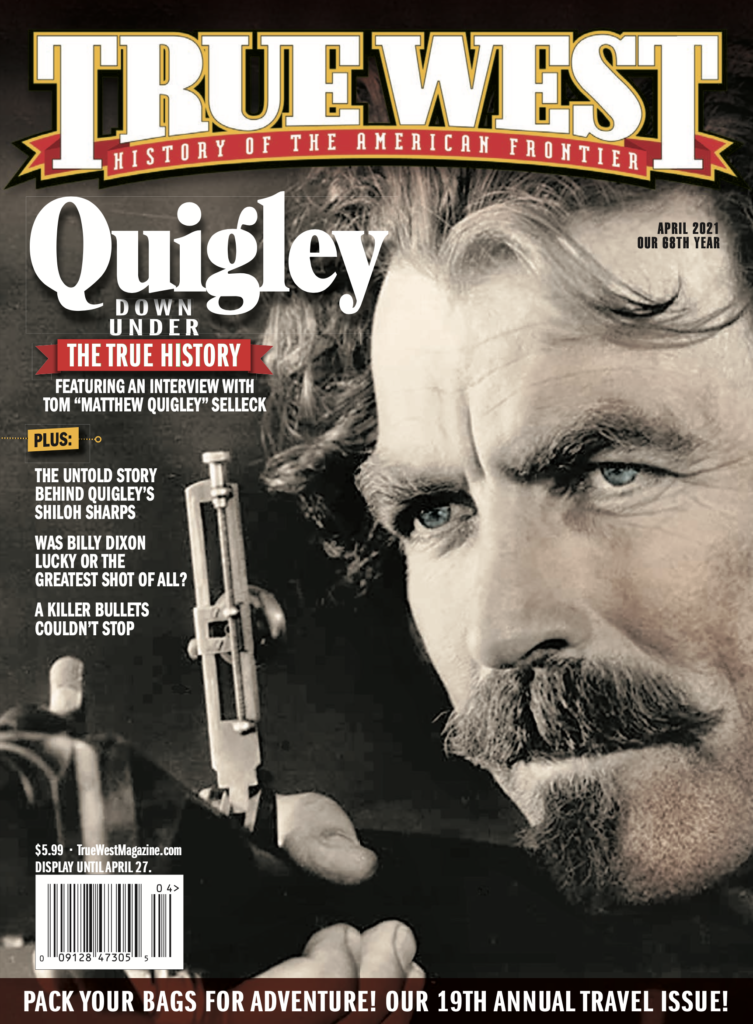

Quigley Down Under, the finest Australian Western, is the story of an American who answers an ad looking for the world’s best long-distance marksman, and finds himself in Australia, employed by wealthy rancher Marsten (Alan Rickman). Then Quigley realizes, to his fury, that Marsten’s hired him to slaughter Aboriginals. Star Tom Selleck remembers, “He became the avenging angel for the Aboriginal people. It was really a terrific script. I worked hard in preparation. I’m very, very proud of Quigley.”

– COURTESY PAN-CANADIAN FILM DISTRUBUTORS –

– COURTESY BUNYA PRODUCTIONS/SWEET COUNTRY FILMS –

From Jimmy Blacksmith to Sweet Country

By the late 1960s, American Westerns were looking at the problems of Indians’ assimilation, whether for or against their will, and Australian films were examining their parallel issues. With many echoes of Tell Them Willie Boy is Here (1969), in the true turn-of-the-century The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978), Tommy Lewis is a half “Abo” young man raised by a well- meaning but clueless minister (Jack Thompson), leaving him unfit for either culture. Despite his incredible forbearance, the abuse he receives after marrying a white girl drives him to a homicidal spree. Lewis later played the terrifying escaped killer in Red Hill (2010), whose story is much akin to Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), with a small-town policeman uncovering a racism-based miscarriage of justice. In 2017’s Sweet Country, set in 1920s Northern Frontier, and far away from law, an Aboriginal man (Hamilton Morris) shoots a white in self- defense, but goes on the run, knowing he won’t be treated justly.

– COURTESY SONY PICTURES –

Since filmmaking began, Australian’s love of tales of pioneering and adventure has produced a steady stream of fine Westerns that stand up to the best of our work, and are as enjoyable for their differences as for their similarities. One need look no further than Simon Wincer, who not only directed the finest of all Australian Westerns, Quigley Down Under, but first came to our shores and directed the best TV Western of all time, Lonesome Dove. Nearly all of the films discussed, and many more, are available through streaming services, or on disc.

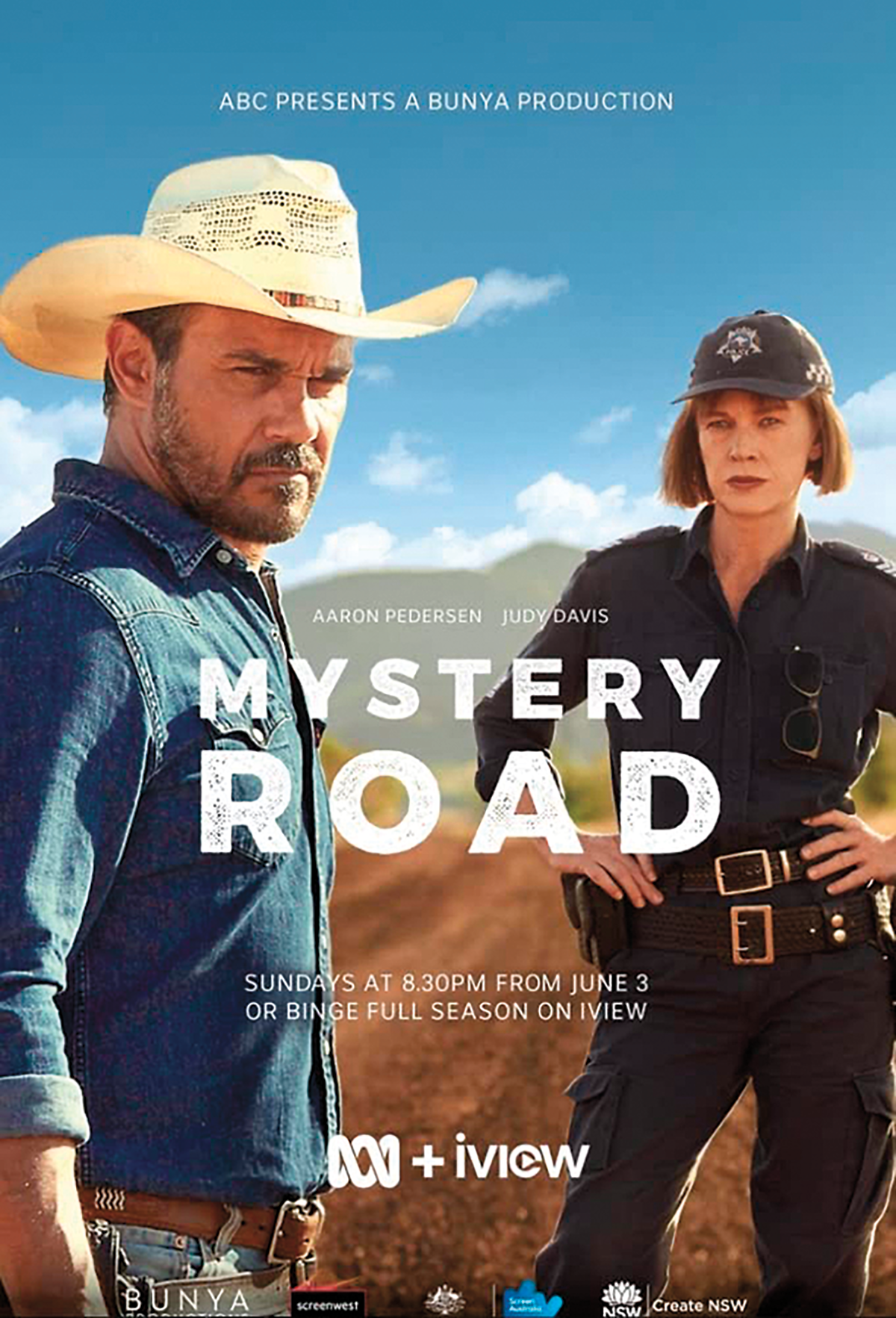

Home Video Review: Boney and Mystery Road – Longmire’s Aussie Cousins

In 1971, a year after Tony Hillerman’s The Blessing Way created the Rez mystery genre, Australian television filmed the first of Arthur Upfield’s Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte mysteries, first published in 1929. The series Boney concerns a mixed- race police detective who moves seamlessly between the White and Aboriginal worlds to solve crimes. Caucasian New Zealander James Laurenson played the ground-breaking role. Forty-two years later, Aaron Pedersen, an actor of Aboriginal decent, starred as indigenous Detective Jay Swan, investigating the deaths of young mixed-race girls in Mystery Road, a wise and tough drama that led to a sequel, Goldstone, and then a Mystery Road series. The Mystery Road movies and series are available on Amazon Prime. Currently, just one episode of Boney is available on YouTube.