— John Grabill, Courtesy Library of Congress —

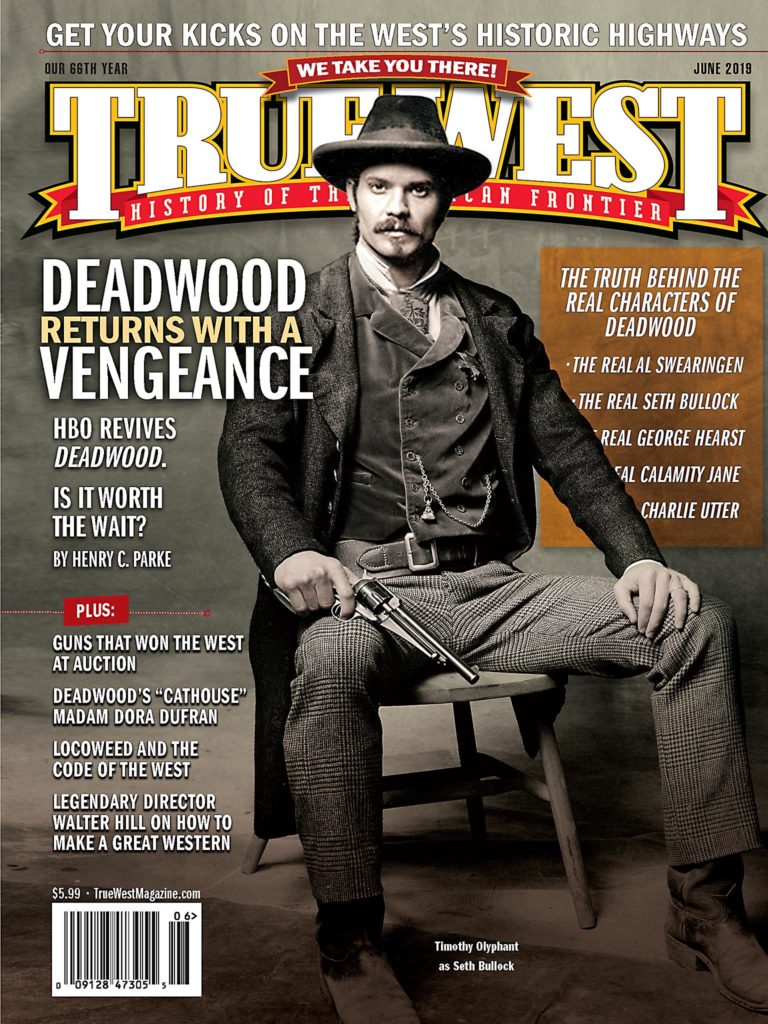

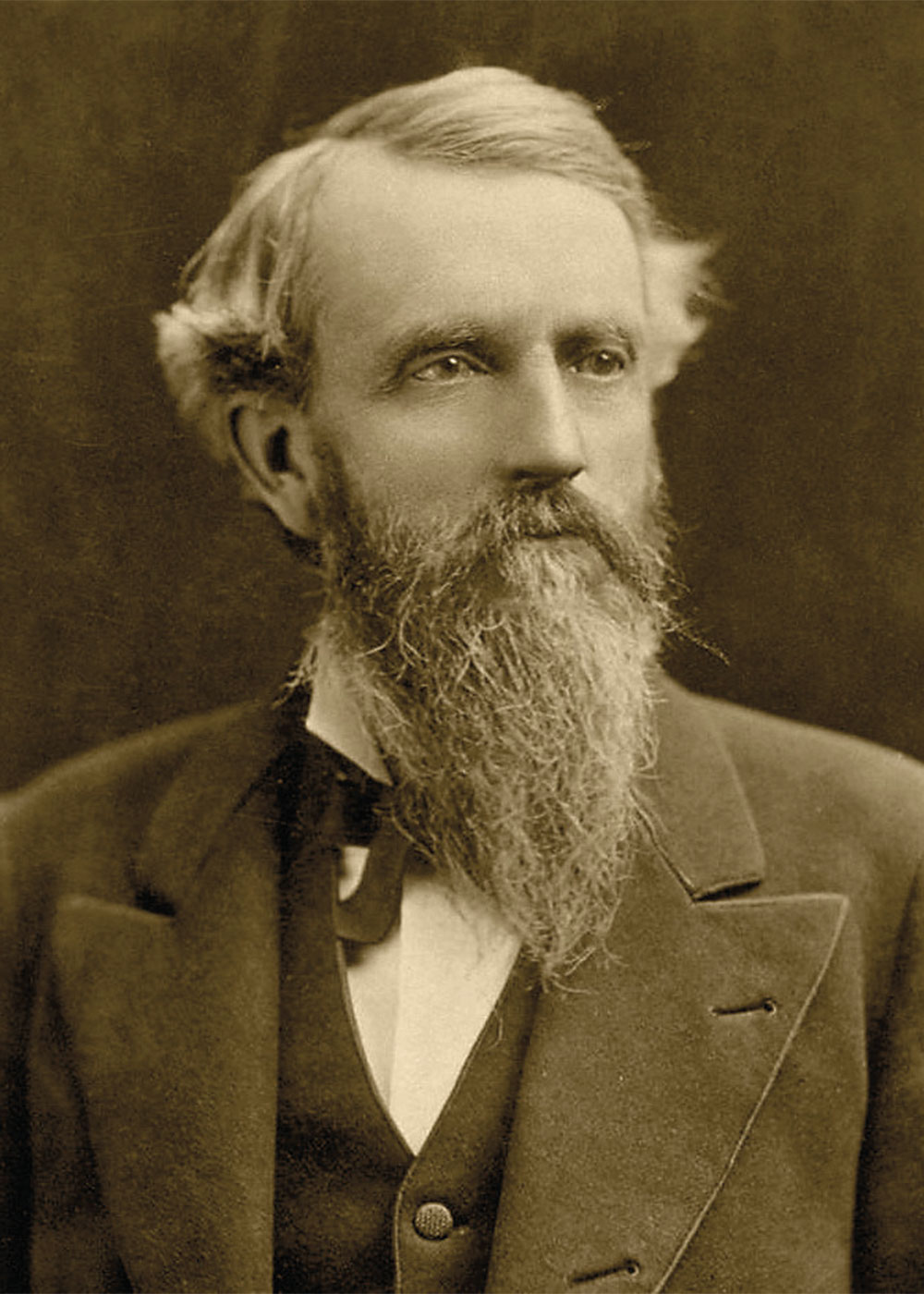

As students of both broadcast entertainment and Western history should be aware, there are two George Hearsts, and the contrast between them could not be greater. While one is a semi-fictitious villain whose malevolence dominates the HBO award-winning series Deadwood, the other—the real George Hearst—was an internationally recognized philanthropist and a man of proven integrity.

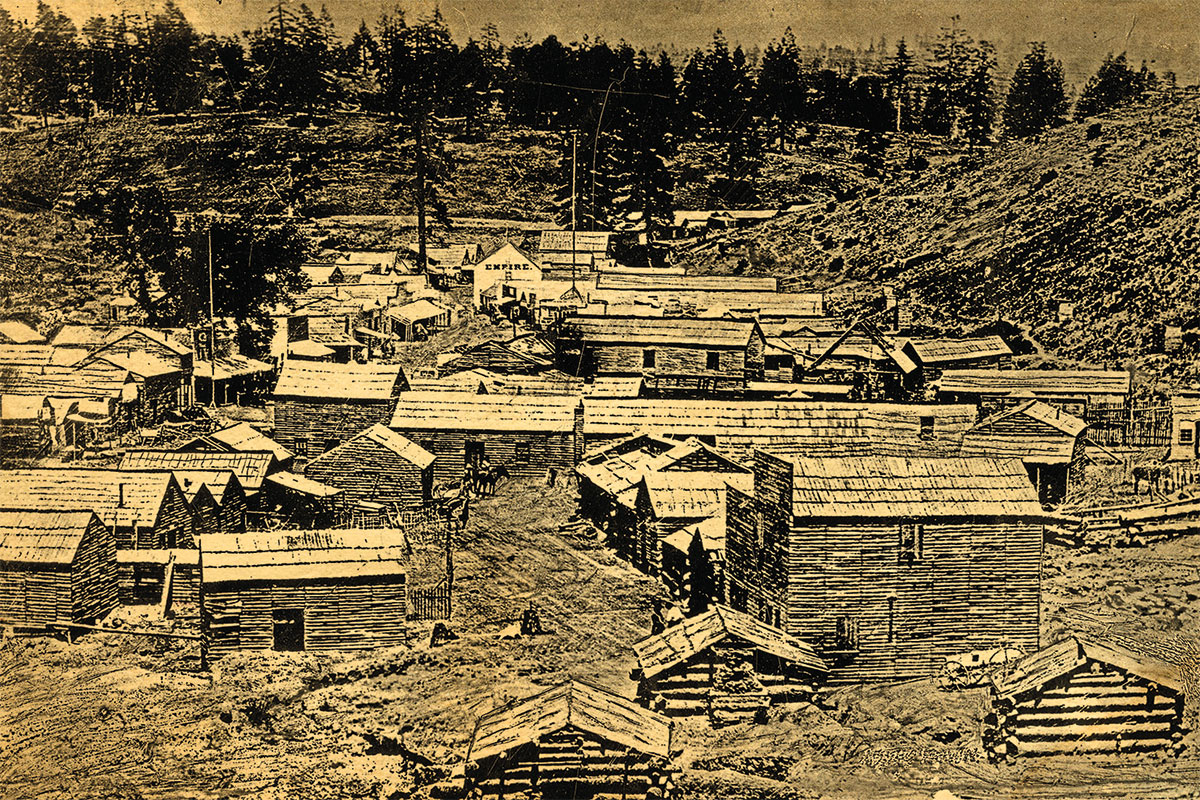

— True West Archives —

Shortly after his appearance in HBO’s interpretation of the rawboned mining camp of Deadwood, Hearst—as brilliantly played by Gerald McRaney—makes clear that he has only one thing in mind: the acquisition, regardless of cost or misdeed, of viable gold claims. He is a man obsessed, a misanthrope with no regard for the thoughts or wellbeing of others. Growing increasingly malevolent over the next several installments, he lops a finger from the hand of Al Swearingen, attempts to rape the widowed Alma Garrett prior to forcing her to sell him her rich claim, and orders or indirectly causes the cold-blooded murders of several of the town’s residents. In the series’ final episodes, he decides to leave Deadwood, but only after importing an army of gun thugs to corral the town. But rest assured, with a new HBO feature in the offing, we haven’t yet seen the last of George Hearst.

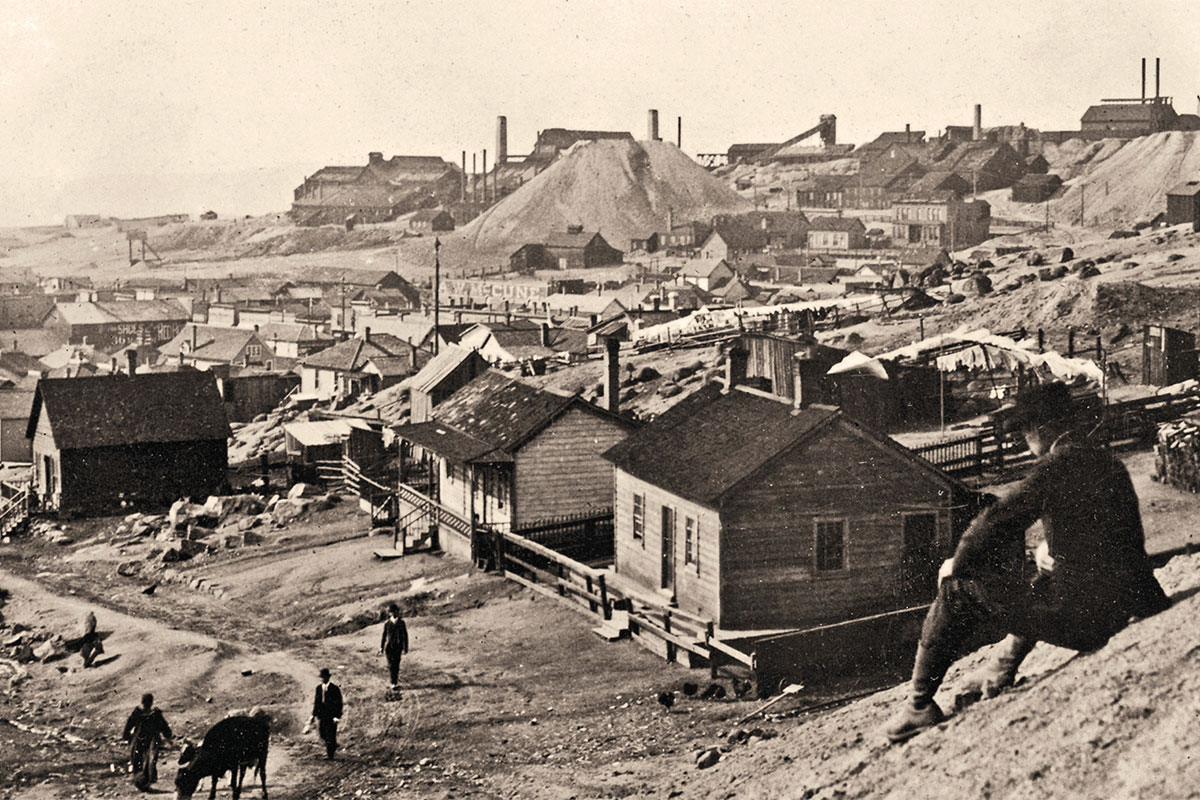

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

In creating the Deadwood version of Hearst, series writer/executive producer David Milch followed the same course he had taken with several of his other characters. While a number of the Deadwood denizens—Cy Tolliver, Joanie Stubbs and “Doc” Cochran, to name a few—were the products of Milch’s fertile imagination, others, such as Seth Bullock, Al Swearingen, J.B. “Wild Bill” Hickok, “Calamity Jane” Canary, Charlie Utter, and yes, the Brothers Earp, were based on real people who actually lived in or briefly visited Deadwood during the period covered by the show. While in some instances Milch crafted his characters to maintain at least some resemblance to the actual people upon whom they are based, there are others who bear no similarity to the town’s real men and women. George Hearst is perhaps the most blatant example.

—Timothy Sullvan, Courtesy Library of Congress —

Milch took Hearst’s name, his skill at finding ore-bearing resources, and the fact that he acquired mining property around Deadwood in the 1870s, and from these elements, he fashioned his perfect villain: a murderous, monomaniacal cad, impossible to like. We cheer as lawman Seth Bullock literally hauls Hearst to jail by the ear; we are crestfallen when Trixie’s bullet fails to inflict a mortal wound; and we vainly long for his death—or at least his comeuppance—throughout the entire third and last season of the show.

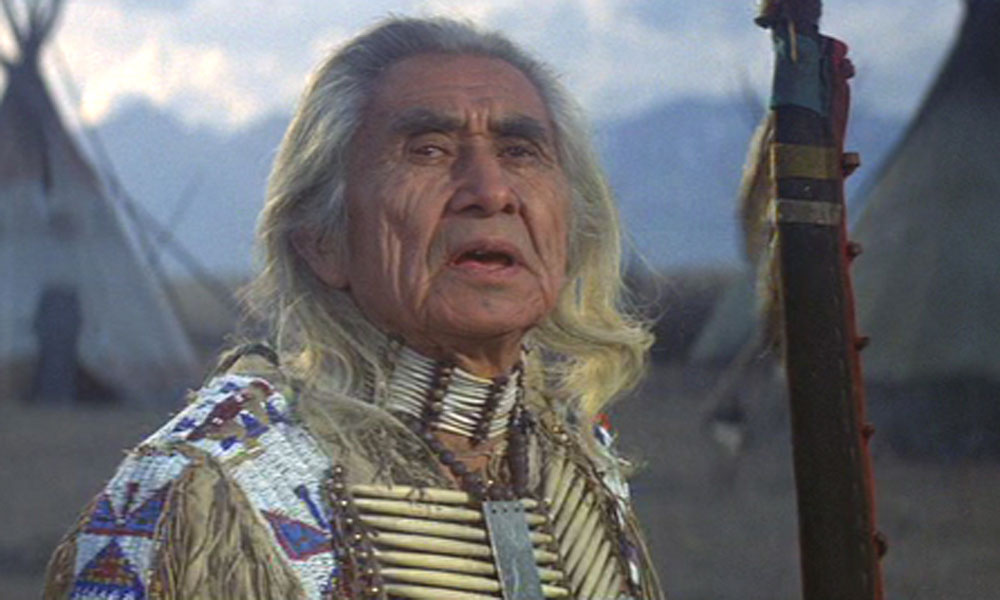

In reality, it is safe to suggest that the real George Hearst, who was the antithesis of a psychopath, would be dumbfounded and outraged at this depiction. Although he was an astute businessman with an uncanny knack for making valuable strikes (apparently, the local Indians really did call him the “Boy the Earth Speaks To”), there is nothing, either historical or folkloric, to suggest that he did so over the dead bodies of his rivals.

In one regard, Deadwood did hew close to the facts: given Hearst’s humble beginnings, his acquisition of a vast fortune was nothing short of phenomenal. If anything, the real Hearst’s life is far more engrossing than that of his fictional counterpart.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

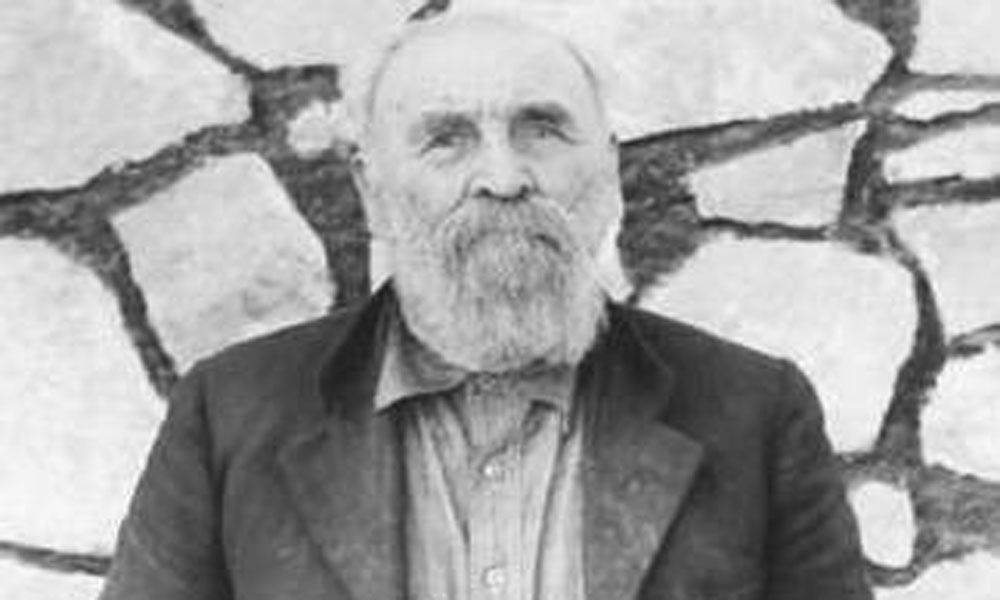

George Hearst was born in 1820, to a debt-ridden Franklin County, Missouri, farming family, and grew up without the benefit of much formal schooling. However, the French miners at the local lead mines allowed George and his friends to “prospect.” As he later recalled, “The miners let us young fellows…pick into the big banks of dirt. We use[d] to dig down and get free bits of lead. Sometimes we made from four to six bits a day.”

The informal education he acquired at the local mines would prove invaluable, and—coupled with his natural gift for sniffing out rich veins of ore—would ultimately make him one of the wealthiest men of his time, and arguably the most knowledgeable on the subject of mining.

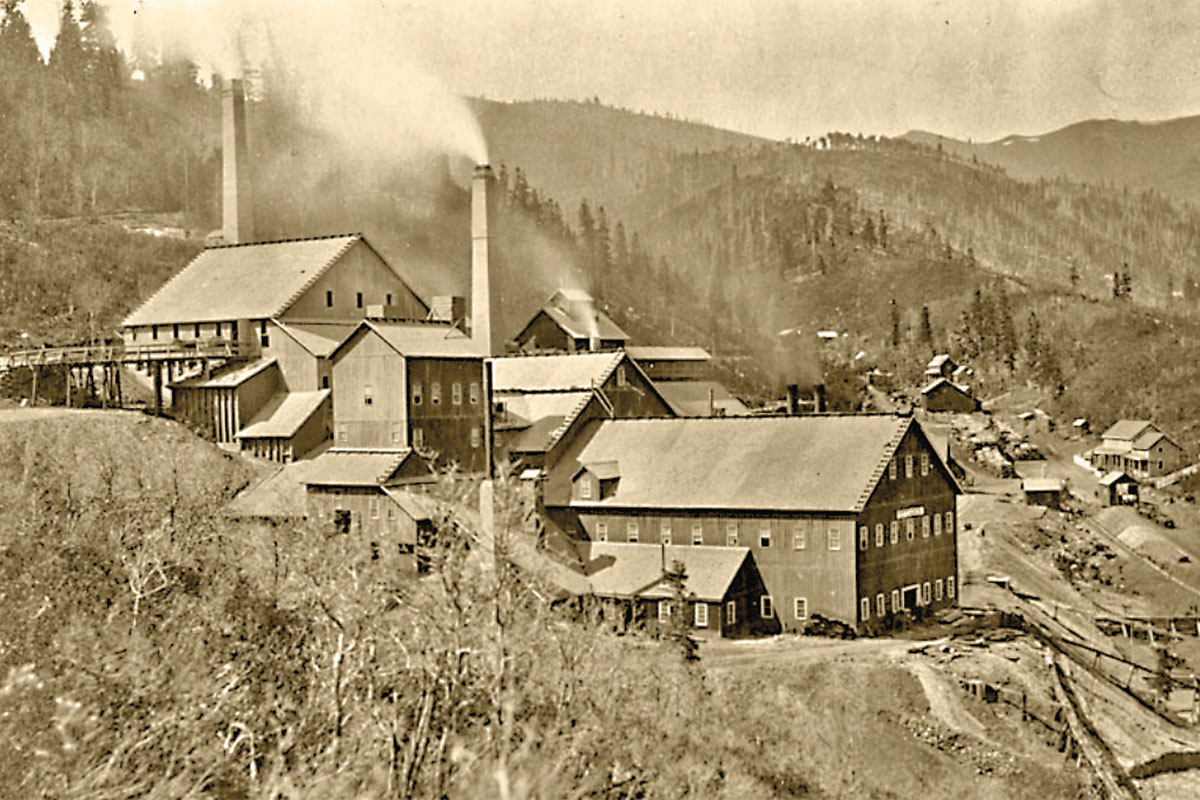

— True West Archives —

Hearst’s father died in 1846, leaving the family heavily in debt. George, now in his mid-twenties, worked desperately to make the farm pay, while at the same time reading every book he could find on mining. Over the next three years, he also leased lead claims, which generated enough profit to satisfy his father’s debts.

By this time, gold had been discovered in California, and—bitten by the gold bug —young Hearst soon took leave of his sister and widowed mother, and along with two cousins, booked passage on a wagon train bound for the West Coast. After a rugged crossing, they arrived in the wide-open mining camp of Hangtown, and proceeded to try their luck at mining.

Their first experience in the goldfields was disastrous. As the year drew to a close, the three had only forty dollars among them.

— Courtesy True West Archives —

The next year, however, brought far better results. The three prospectors moved to Grass Valley, and discovered a gold-bearing ledge between there and Nevada City. It was the beginning of a career that would consume Hearst for the rest of his life.

Hearst sold the mines in early 1852, establishing a pattern he would repeat for years to come: Buy a promising property, prove it up, and sell it at a profit. As his financial status grew, so, too, did his reputation. Recalled a contemporary, “George Hearst was probably the greatest natural miner who ever had a chance to bring his talents into play on a large scale. He was not a geologist, had no special education to start with…but he had a congenital instinct for mining.”

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

In 1859, Hearst responded to the news of the silver strikes at Nevada’s Comstock Lode. With his gift for recognizing high-yield properties, he purchased an interest in the Ophir Mine. The claim paid for itself many times over. After the rock had been crushed and processed, the extracted silver and gold was worth up to $10,000 per ton—over $300,000 in today’s currency.

George returned to Missouri in 1860 to visit with his terminally ill mother. While there, he reacquainted himself with 19-year-old neighbor and distant cousin Phoebe Apperson, who had been little more than a child when he had left home.

— True West Archives —

The 41-year-old Hearst was smitten, and apparently Phoebe returned his affections. When her parents disapproved, the couple eloped, wedding in June 1862. By all reports, the Hearsts’ marriage was a love match. As strong in her own right as her husband, Phoebe would earn a reputation as a lifelong suffragist, feminist and philanthropist.

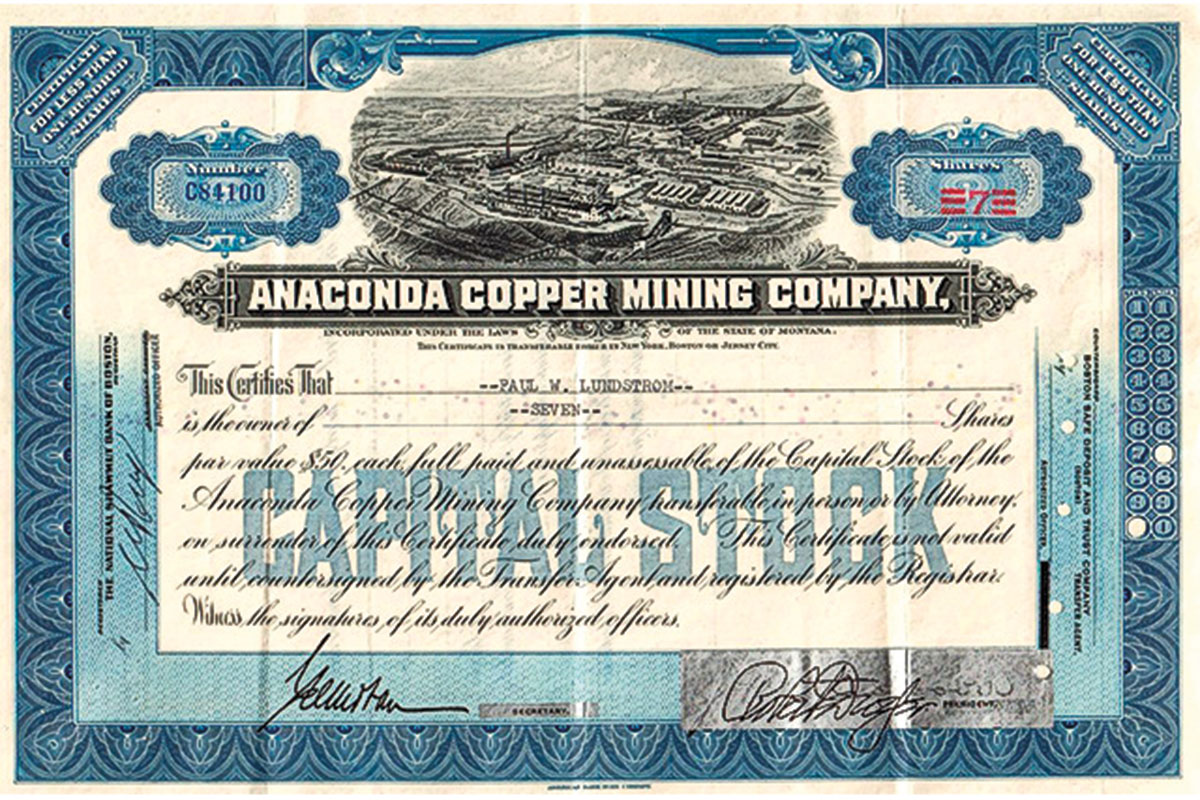

Over time, George diversified, profitably investing in real estate, cattle-raising and horse-breeding. But it was in the field of mining that he truly excelled. He went on to make strikes that would become legend: the Ontario and Daly mines near Park City, Utah, which would go on to pay monthly dividends worth millions today; the Anaconda in Montana, the world’s largest and most profitable copper mine; and his biggest strike of all, just a few miles outside of Deadwood.

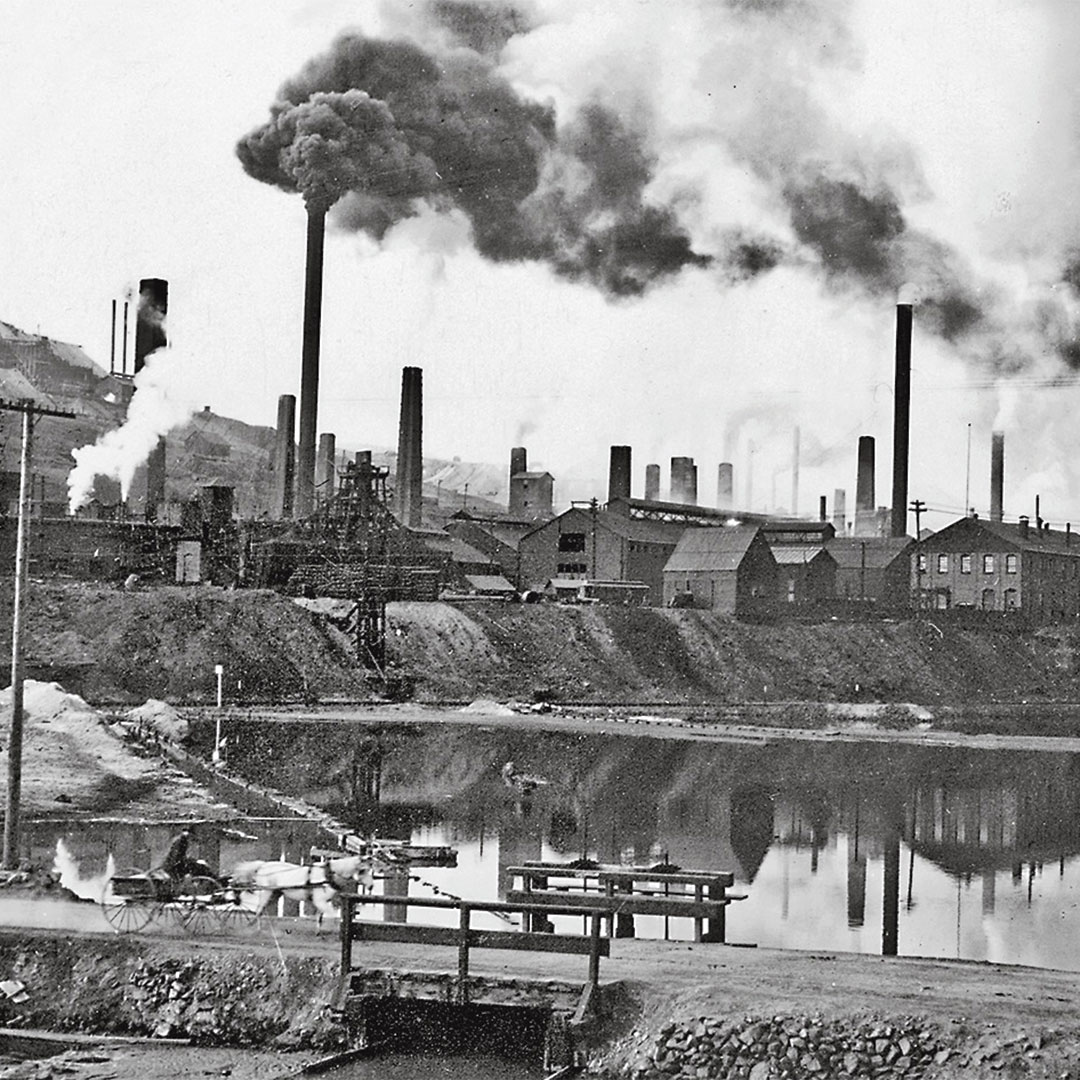

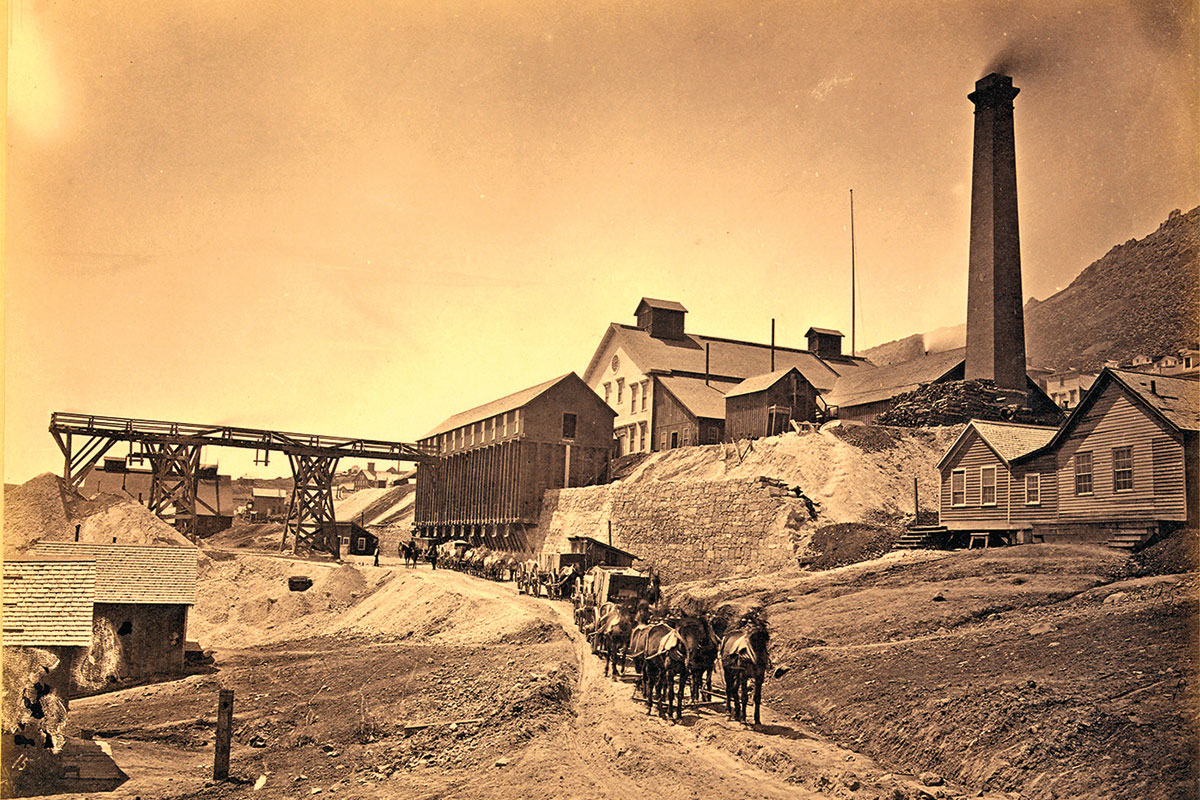

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

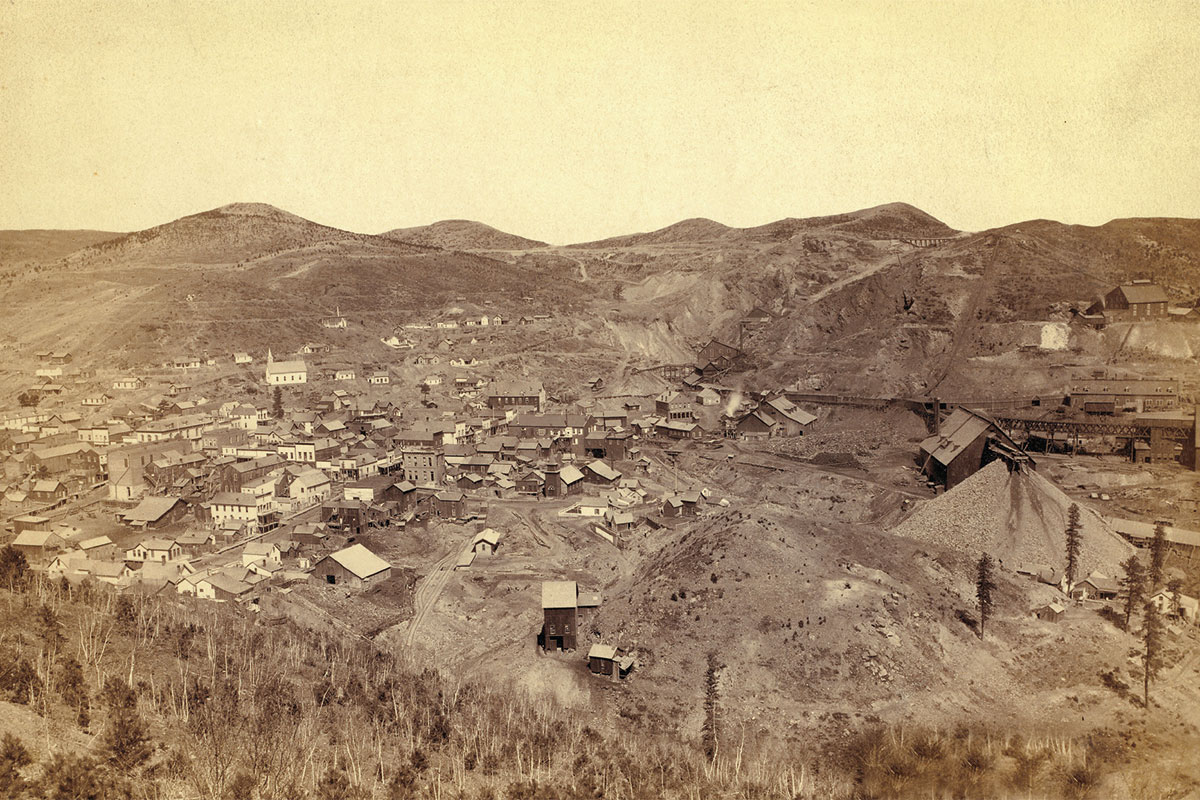

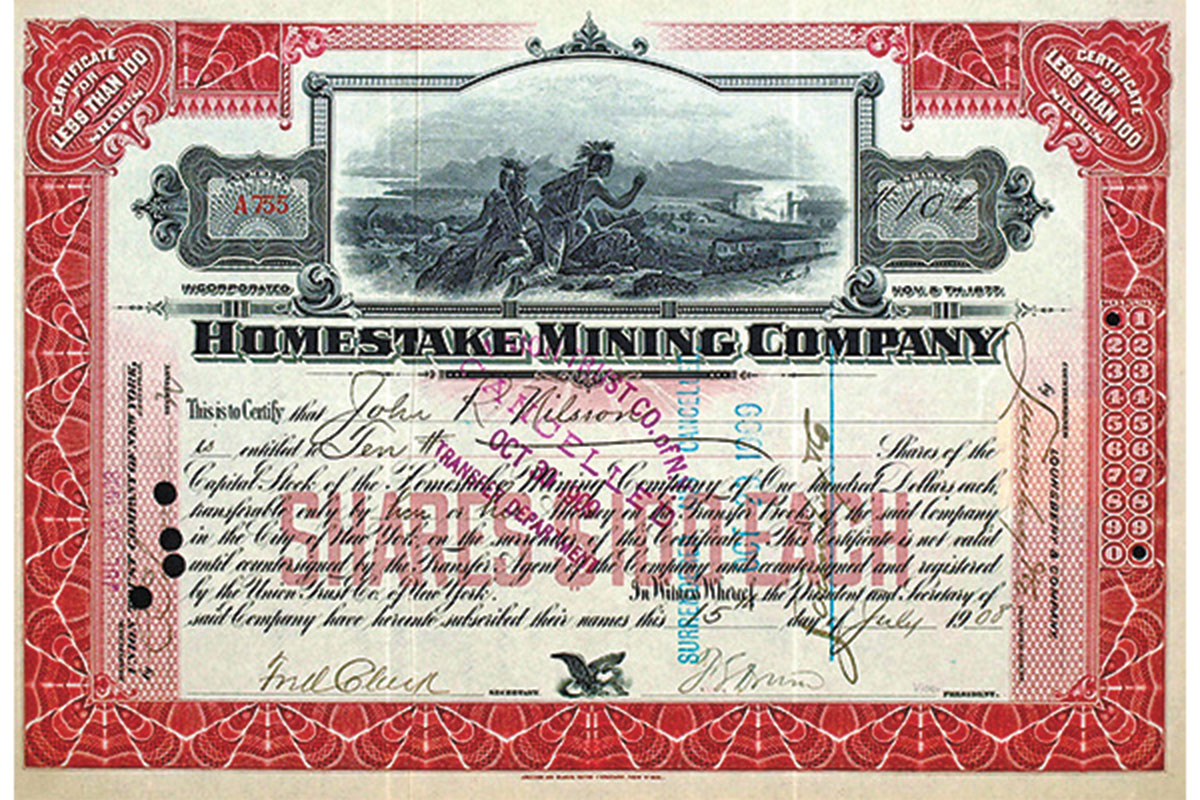

As the Deadwood series shows, Hearst visited the town in 1876, having seen and been impressed by samples of Black Hills gold. He and a partner bought a controlling interest in a mine in nearby Lead, naming it the Homestake. They then bought up all 250 claims surrounding it, on over 600 acres.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

There were several gold veins on the surface, but Hearst soon discovered that

they converged below in a solid vein of gold that ran up to 500 feet wide, and grew even wider as it went deeper. Over the next 20 years, the mine generated $80 million in revenues—nearly $2 billion in today’s dollars. The Homestake would become the largest and deepest gold mine on the continent, generating over 40 million troy ounces of gold before it ceased operations in 2002.

Interestingly, the Deadwood series is more focused on the celluloid George Hearst’s lack of integrity than his Midas touch. And it is here that reality and creativity drift the farthest apart.

The historic Hearst was universally known for his altruism and strength of character. As a member of the California legislature, and later an elected senator—an office he held with distinction until his death from cancer in 1891—Hearst was respected by Democrats and Republicans alike. As fellow Senator Daniel Voorhees of Indiana recalled, “He had a high manliness of bearing, a gentle kindliness of manner, a winning courtesy, and a native gracious dignity which were magnetic….”

— Courtesy True West Archives —

Referring to Hearst’s fortune, fellow California Congressman Charles N. Felton wrote, “[N]o part of it was extorted from others, no part soiled with dishonor; [he] left a pure legacy….”

Nor was Felton unique in his opinion. Senator and Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Clunie said, “[N]o man ever accused [him] of one dishonest act. I have walked by his side on many occasions. I have seen him approached by broken-down old miners…and, with tears in his eyes, [he] would put his hand in his pocket and furnish them relief.”

Senator George Vest of Hearst’s home state of Missouri agreed: “He did not hide nor hoard the wealth acquired by self-denial and long endeavor, but gave cheerfully and liberally to deserving objects.”

Hearst was as open-handed with his counsel as he was with his purse. Fellow California Senator and life-long friend Leland Stanford wrote, “Among his colleagues…his counsel was constantly sought and his judgment relied on, for it was calm and keen.”

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Apparently, Hearst could also be quite funny at times. Biographer Judith Robinson writes that he “had a quiet sense of humor and a twinkle in his eye.” According to Nevada Senator William M. Stewart, “He…had a vein of humor which amused and fascinated the learned as well as the illiterate. He was at home with men of all conditions….”

Even allowing for hyperbole, this is clearly not the man we have come to loathe on Deadwood. Hearst ranked high in the estimation of the leading men of his era, as well as the hard-rock miners—and there were some 5,000 working for him at the time of his death—who simply called him “George.”

As the saying goes, George Hearst “never got above his raising.” At his death, a memorial present ation was given in both the Senate and the House of Representatives. It read in part, “Change in fortune made no change in the man. As a millionaire, as a senator of the United States, he remained the same simple George Hearst who mined on the Feather and Yuba in the fifties…. He had a manly, a gentle, and a loving heart.”