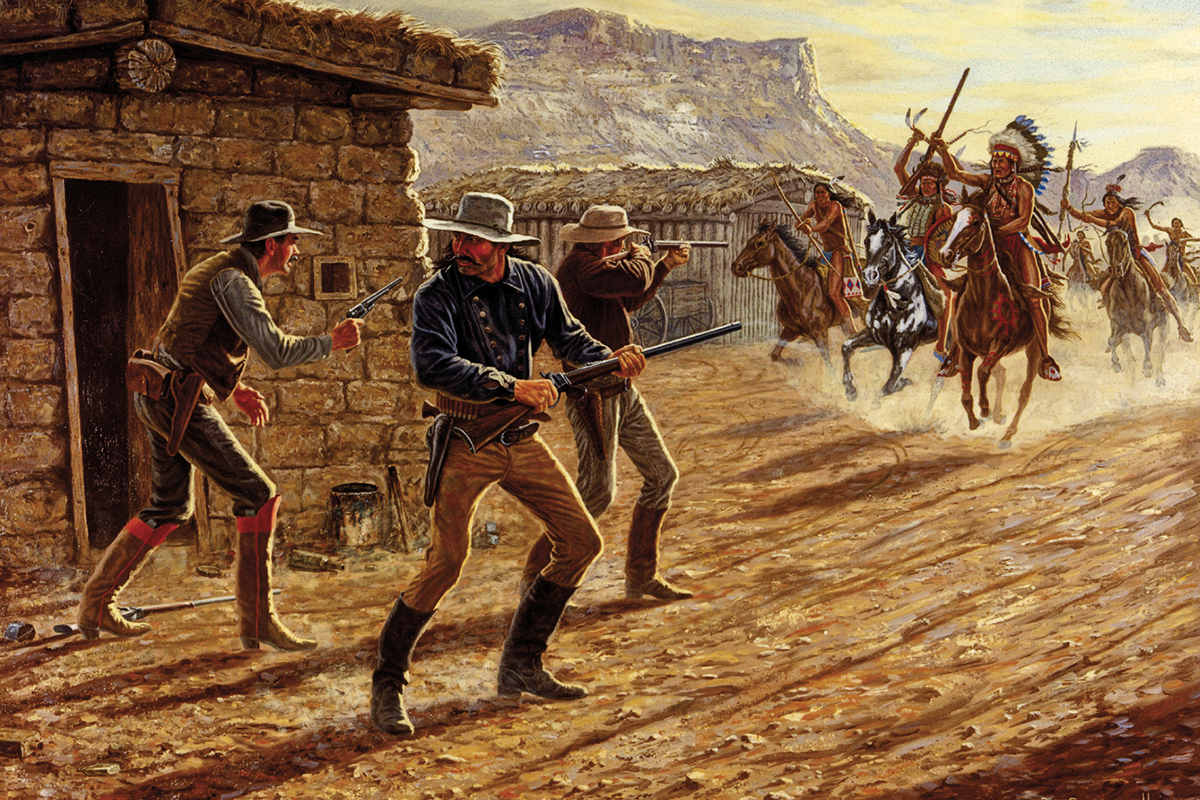

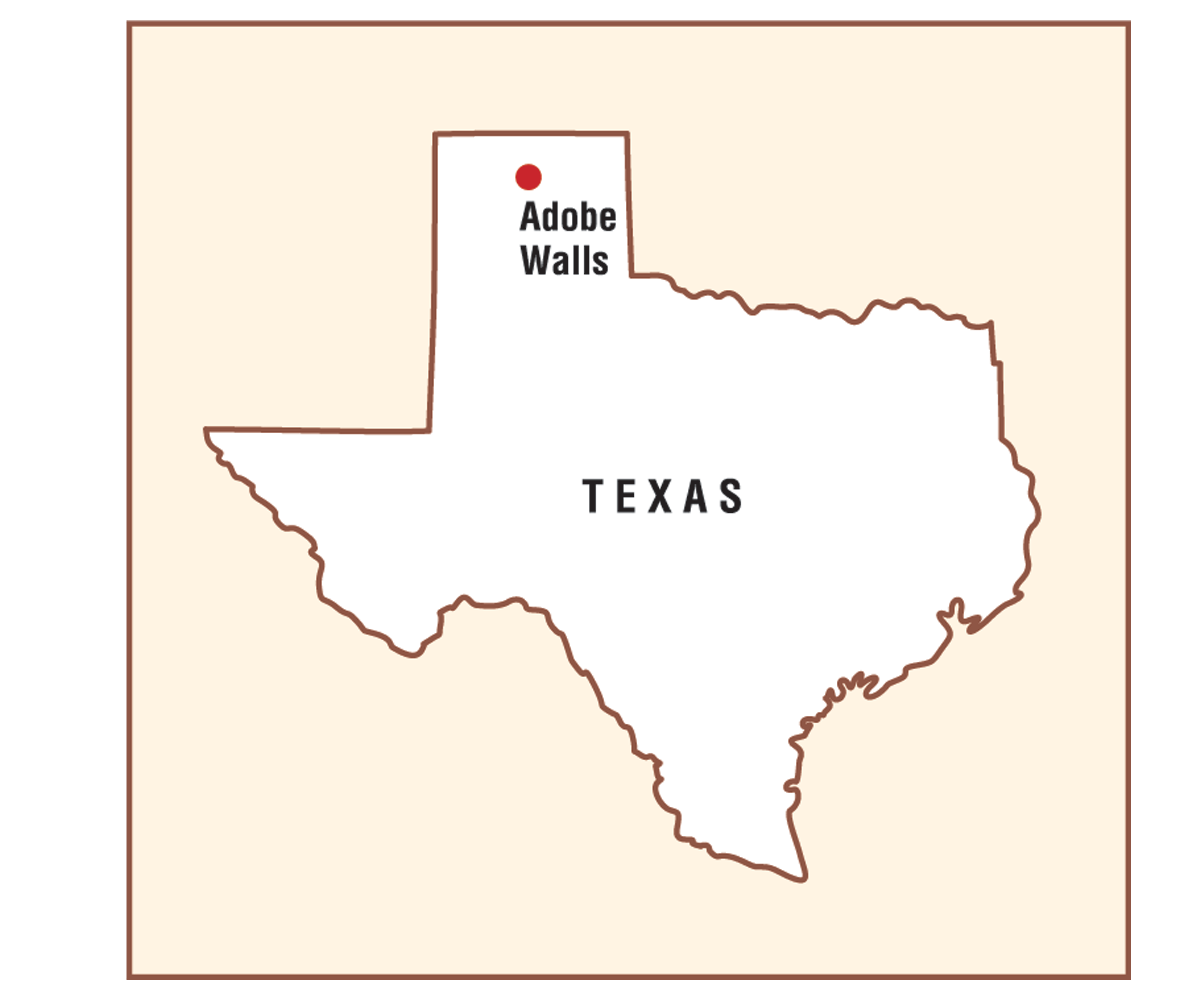

THE SECOND BATTLE OF ADOBE WALLS FEATURES THE LEGENDARY 1,538- YARD SHOT HEARD ’ROUND CAMPFIRES EVER SINCE: June 27, 1874

– ILLUSTRATIONS BY BOB BOZE BELL; PHOTOS TRUE WEST ARCHIVES UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED–

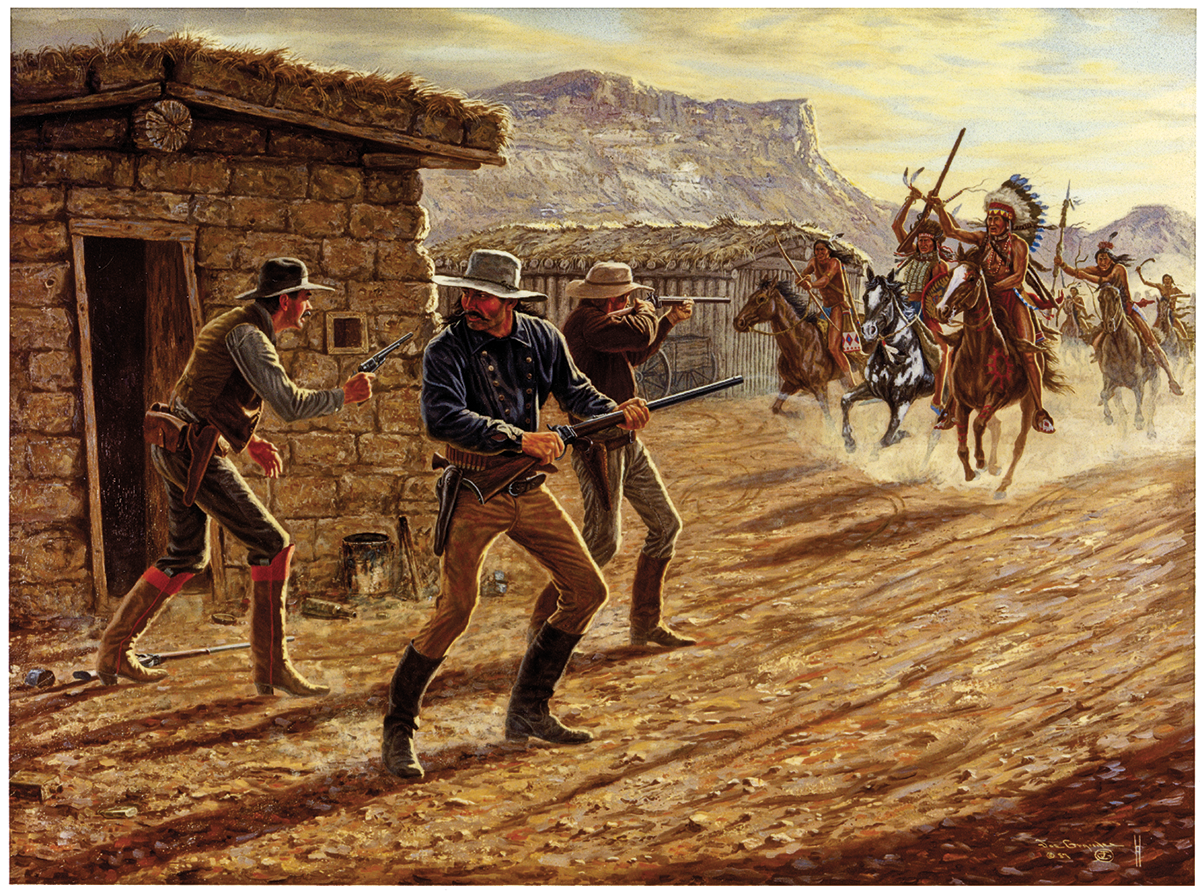

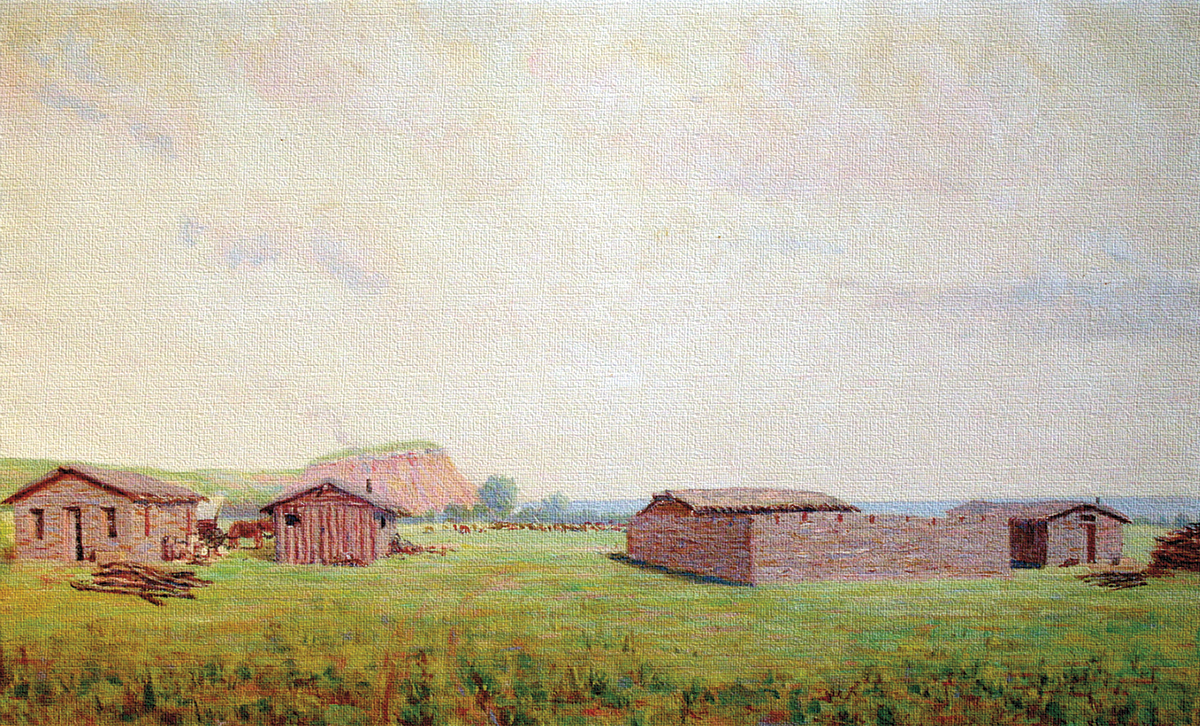

The Comanches and their Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne and Araphaho allies are hell-bent on driving buffalo hunters off their land. The hunters have already decimated the herds on the Northern Plains. Now these hunters have set up shop near Adobe Walls, deep in Comanche territory, in the Texas Panhandle.

A force of up to several hundred warriors, led by a messiah-like medicine man named Isa-tai and by Comanche Chief Quanah Parker, advance at day- break on the settlement. The attackers are counting on the element of surprise, but when they charge at dawn, they dis- cover most of the hunters are awake, repairing a broken ridgepole.

The defenders, 28 men and one woman, repel the initial charge with a loss of only two men who were asleep in a wagon. The first wave almost carries the day as the attackers are close enough to pound on the doors and windows with their rifle butts. At such close range, the defenders are not able to use their superior firepower and end up fighting with pistols and lever-action rifles.

After repulsing the initial attack, the buffalo hunters hold back the attackers with their long-range Sharps rifles. Twenty-year-old Bat Masterson carries one, as does sharpshooter Billy Dixon. Thirty-plus long-range Sharps are quickly deployed to defend the camp. The 15 attackers they kill are scattered so close to the buildings that the Indians cannot retrieve their comrades’ bodies. By noon, the Indians take up positions around the besieged hunters, maintaining a steady barrage of fire into the buildings. By two p.m., the attackers retreat beyond rifle range to reconnoiter. By four p.m., the hunters are able to leave the buildings; they retrieve weapons from the dead and bury their bodies.

On the second day, the defenders drag away the dead horses and oxen (the attackers have killed all 28 belonging to the Shadler brothers) to “prevent the evil smell from reaching the buildings,” Dixon recalls in his autobiography.

During a lull in the fighting, several hunters arrive at Adobe Walls, increasing the number of defenders to more than 30 men. Hunter Henry Lease volunteers to ride to Dodge City, Kansas, to seek out further reinforcements.

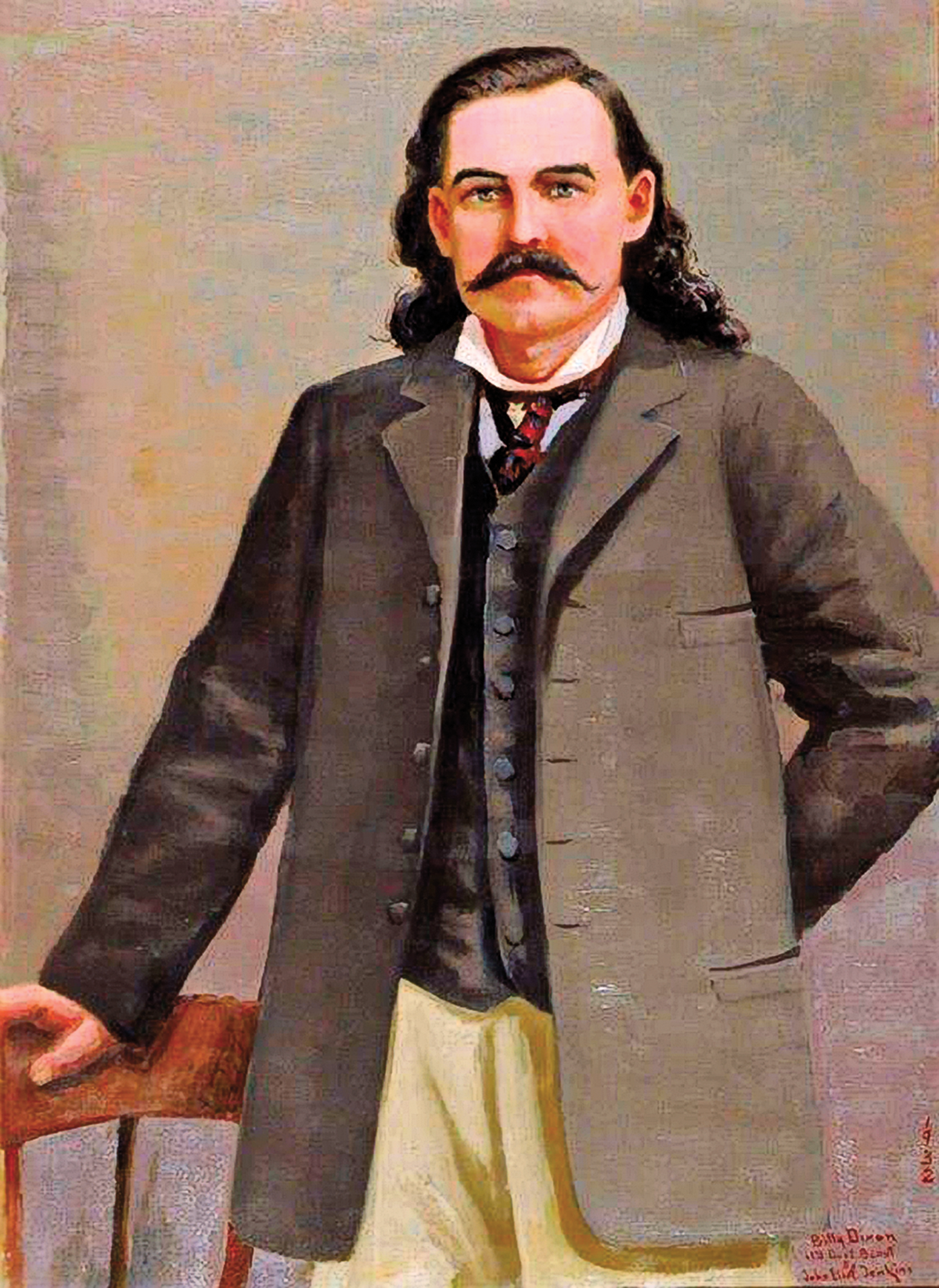

On the third day, 15 Indian warriors ride out on a bluff nearly a mile away to survey the situation. At the behest of one of the hunters, William “Billy” Dixon, a crack shot, takes aim with a borrowed .50-90 “Big Fifty” Sharps rifle. After calculating the drop and the wind factor, he fires and cleanly drops a warrior from atop his horse. Dixon later says, “I was admittedly a good marksman, yet this was what might be called a ‘scratch’ shot.”

Tradition claims Dixon’s shot so discourages the Indians that they decamp and give up the fight.

Quanah’s Headlong Charge

“There was never a more splendidly barbaric sight. In after years I was glad that I had seen it. Hundreds of warriors, the flower of the fighting men of the southwestern Plains tribes, mounted upon their finest horses, armed with guns and lances, and carrying heavy shields of thick buffalo hide, were coming like the wind.

“Over all was splashed the rich colors of red, vermillion and ochre, on the bodies of the men, on the bodies of the running horses. Scalps dangled from bridles, gorgeous war-bonnets fluttered their plumes, bright feathers dangled from the tails and manes of the horses, and the bronzed, half-naked bodies of the riders glittered with ornaments of silver and brass.

“Behind this headlong charging host stretched the Plains, on whose horizon the rising sun was lifting its morning fires. The warriors seemed to emerge from this glowing background.”

—Billy Dixon

The Sharpshooter

Originally from Henryville, Quebec, Canada, Bat Masterson, 20, is the youngest of the 28 buffalo hunters at Adobe Walls. Masterson serves as a civilian scout during the Red River War of 1874-75. A shooting on January 24, 1876 in Sweetwater (now Mobeetie), Texas, becomes the basis for his gunfighter reputation.

Bad Medicine

In the spring of 1874, medicine man Isa-tai (translates as “Wolf’s Vulva” or “Coyote Vagina”) began claiming he had true “puha,” Comanche for “power,” and that anyone who followed him would be immune to the White Man’s bullets.

On May 26, 1874, Quanah Parker massed his fighters on a high bluff next to the Canadian River. Isa-tai appeared before the assembled warriors naked, except for a cap of sage stems. His body was painted yellow, as was his horse’s body, repre- senting invulnerability. Many of the other braves had painted their bodies yellow as well to demonstrate their own beliefs in Isa-tai’s puha and that a moment of destiny had arrived to bring them their redemption.

When they lose the battle in June, many of the warriors are understandably upset with Isa-tai. One of the Cheyenne men strikes the medicine man in the face with a riding quirt. Another, the father of a young warrior who was killed, demands that, since Isa-tai is immune to the White Man’s bullets, he should go down and retrieve his son’s body. Before Isa-tai responds, one of the “Big Fifties” reaches the group, knocking the rider next to him out of the saddle, while another Sharps bullet kills Isa-tai’s horse.

Isa-tai gives an excuse for the debacle, blaming the Cheyennes’ killing of a skunk the day before the battle as jinxing his medicine. Nobody believes him. In spite of Isa-tai’s bad medicine, he continues on his merry way, spreading his false gospel.

The “Big Fifty”

To make his long shot, Billy Dixon fires a single-shot .50-90 Sharps rifle. These guns are so powerful, they can put down a 2,000-pound buffalo at 1,000 yards, similar to this 1874 model in .44-77 caliber.

– RIFLE COURTESY PHIL SPANGENBERGER –

An Examination of the Shot

Although Dixon himself claimed it was a “scratch shot,” many modern shooters try to debunk the shot he made with the borrowed .50-90 Sharps. In the fall of 1992, friend and fellow gun-writer Mike Venturino was invited along with the Shiloh Sharps owners to travel to the Yuma Proving Grounds in Arizona, to use some then-newly declassified radar devices to test the performance of several types of ammunition.

Using a machine rest modified from a gun carrier from a Russian T-72 tank, they started firing away. For the first Sharps shot, with the gun carriage elevated to 35 degrees, a 675-grain bullet, pushed by 90 grains of FFg black powder, and with a muzzle velocity (mv) of only 1,216 feet per second (fps) launched the bullet over 3,600 yards distant. That’s 10,800 feet— over two miles!

– ROBERT BLOCK –

The scientists couldn’t believe it, so a second round was touched off. This time the lead projectile weighed 650 grains with a mv of 1,301 fps. Using the same 35-degree elevation, the bullet landed 3,245 yards away.

After one of the mathematicians calcu- lated the data, he suggested they reduce the elevation to about 4.5 to 5 degrees to duplicate Billy Dixon’s shot. When this was done using the same load, the lead slug landed 1,517 yards downrange— almost the exact range of Dixon’s contro- versial shot. A five-degree muzzle eleva- tion can easily be achieved with only the rear barrel sight on a Shiloh Sharps.

-Phil Spangenberger

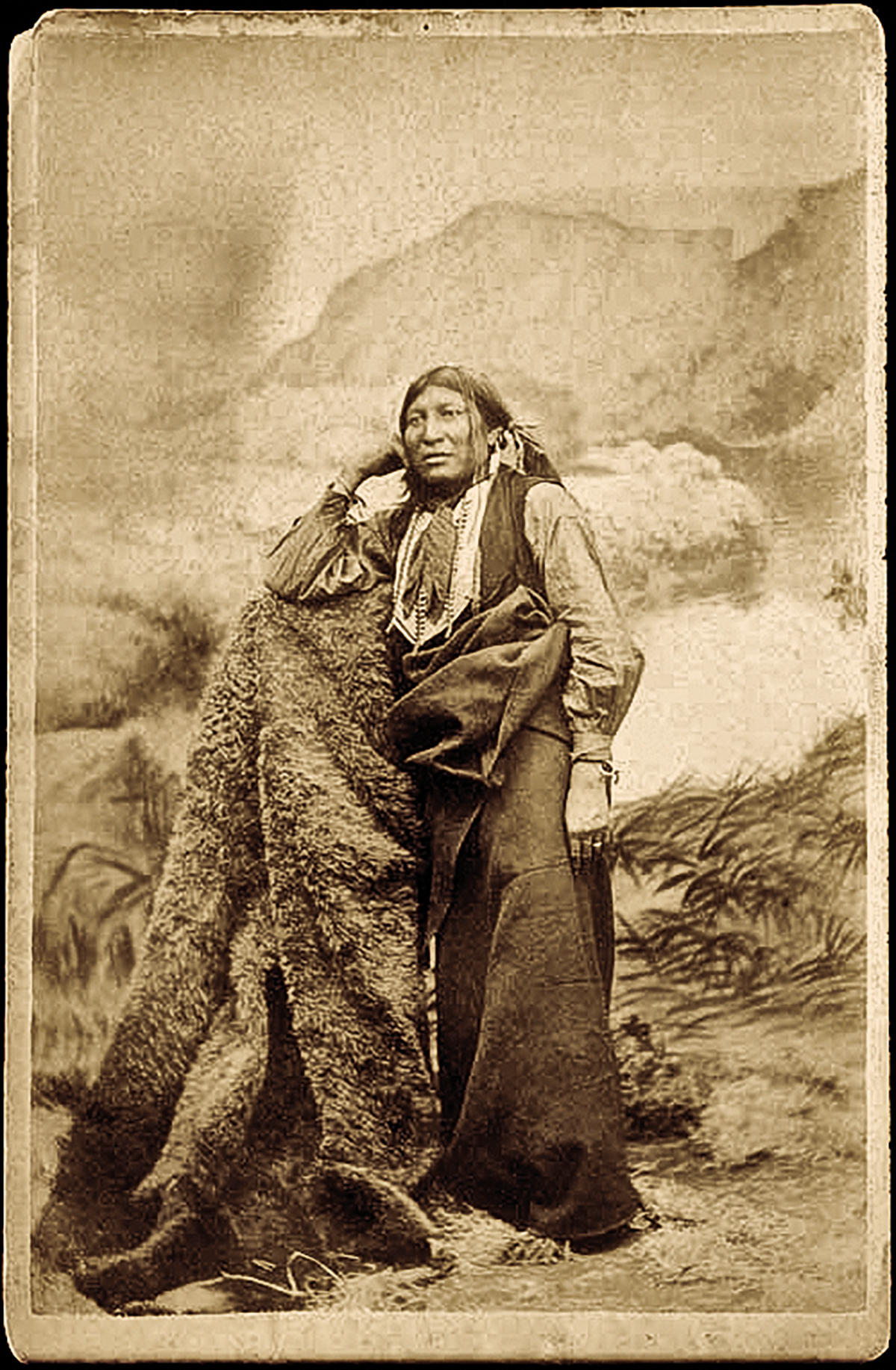

Quanah Parker’s Version of the Fight

“We at once surrounded the place and began to fire on it,” recalled Quanah Parker, shown above, at right. “The hunters got in the houses and shot through the cracks and holes in the wall. Fight lasted about two hours. We tried to storm the place several times but the hunters shot so well we would have to retreat. At one time I picked up five braves and we crawled along a little ravine to their corral, which was only a few yards from the house. Then we picked our chance and made a run for the house before they could shoot us, and we tried to break the door in but it was too strong and being afraid to stay long, we went back the way we had come.”

– PORTRAIT BY JOHN ELLIOT JENKINS, COURTESY PANHANDLE PLAINS MUSEUM –

From Adobe Walls to Quigley Down Under

According to a published 1887 government survey, the Sharps was the most- used rifle by professional hide hunters. Over a century later on the silver screen, filmdom’s Matthew Quigley’s 1874 (Shiloh) Sharps quickly earned the respect of the movie’s Australian stockmen when he made his supposedly 1,200-yard bucket shot. In real life, when buffalo hunter Billy Dixon dropped an Indian warrior from 1,538 yards with a borrowed “Big Fifty” Sharps at the Second Battle of Adobe Walls, it caused the warriors to withdraw from the fight. One could say that this was the Old West’s “shot heard ’round the world.” It not only ended the Indians’ attack on the small settlement, but the Sharps cemented a lasting respect with riflemen of all kinds.

Frontiersmen held a healthy respect for anyone armed with a Sharps, forever known as among the most powerful and accurate long-range arms in the West. It’s no wonder the Indians dubbed the 1874 Sharps as the “shoots far” rifle, or the “shoot today, kill tomorrow gun.”

—Phil Spangenberger, True West’s Firearms Editor

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

As news of the Adobe Walls fight spread, more hunters came in for protection and to help defend the settlement. By the sixth day, the garrison grew to about 100 men.

Quanah Parker was wounded in one of the attacks, and some believe this is why the Indians retired without more of a fight. “The Indians probably came to the conclusion that if they remained long enough, charged often enough and got close enough, all of them would be killed, as they were unable to dislodge us from the buildings,” one of the hunters said.

Casualty reports varied. Today, most historians agree that fewer than 30 died during the battle.

By August, Lt. Frank D. Baldwin, with Billy Dixon and Bat Masterson as scouts, arrived at Adobe Walls, where a dozen men were still holed up. The next day, the soldiers and remaining men left Adobe Walls, heading south to join Gen. Nelson A. Miles’ main command on Cantonment Creek. The Indians later burned the place to the ground.

The Adobe Walls fight led to the Red River War of 1874–75, which resulted in the final relocation of the Southern Plains Indians to reservations in what is now Oklahoma.

Recommended: Empire of the Summer Moon by S.C. Gwynne, published by Scribner.