Shorty Harris’s bonanzas and burros were almost as legendary as he was.

Courtesy Eastern California Museum

He may be the last person to have been buried on public property after it had become a national park or national monument. Two years after his death in 1934 a special memorial service was conducted at his grave with some 200 people attending. At the ceremony a bronze plaque was placed with the words, which said in part: “Bury me beside Jim Dayton in the valley we loved. Above me write: Here lies Shorty Harris, a single blanket jackass prospector.”

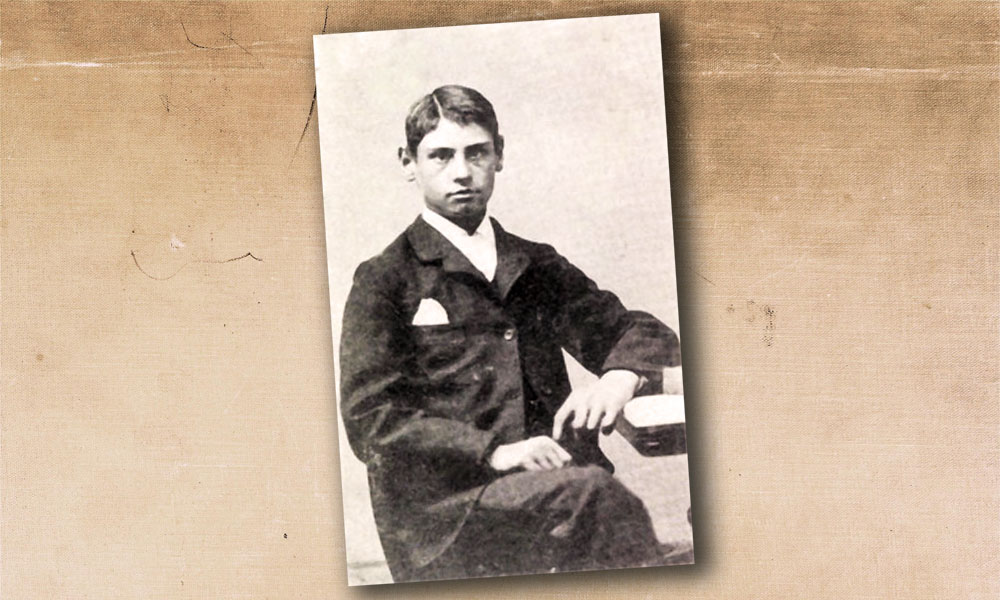

Frank Harris was born, by his own account, on July 21, 1857, in Rhode Island to an Irish father and Scottish mother, both of whom died when he was about seven years old. Adopted by an aunt, he began working at 11 years old in a calico mill. At 14 he ran away from his aunt’s home and worked a variety of jobs in the surrounding states, until at last he got an itch to travel west. By 1878 he had found his way to Leadville, Colorado, which was at the peak of gold and silver mining in the state. He worked for a time as a hard rock miner in shafts and tunnels before he and two friends decided to try their hand at prospecting. They saved enough money to outfit themselves with the typical miner’s necessities, including burros.

Several weeks after leaving Leadville, they made their first strike, staking a claim on a site with a good showing of silver ore, which they subsequently sold for $7,500. This, Harris claimed, was the first real money he ever got. He traveled to Denver to “put on a party that made them all sit up and take notice,” but in six weeks he was “stone broke.”

That was all Harris needed to get hooked on prospecting, and he seemed to have been fortunate in locating good claims as he drifted from Colorado to Wallace, Idaho, and from there to several mining districts in Montana. The mid-1880s found him in Frisco, Utah, and shortly after that, Tombstone, Arizona. From there he journeyed to Virginia City, Nevada, and Bodie, California. But the area where he spent the most time was in the eastern California desert, Death Valley and vicinity. In the Panamint Range he and a partner found ore so rich that, as miners say, “it has the eagle stamped right on it.”

Harris’s use of burros was summed up in an interview he gave a few years before his death:

“All my traveling in this country was done on the hurricane deck of a jackass, and believe me, that’s the way all the big strikes have been made. A jack can go almost anywhere that a mountain sheep can and carry all that a man needs for several weeks. You’ve heard it said that ‘gold is where you find it.’ I can tell you that it’s usually found in places that are hard to get to, and a burro can get there when a horse or a mule would be stalled for good.”

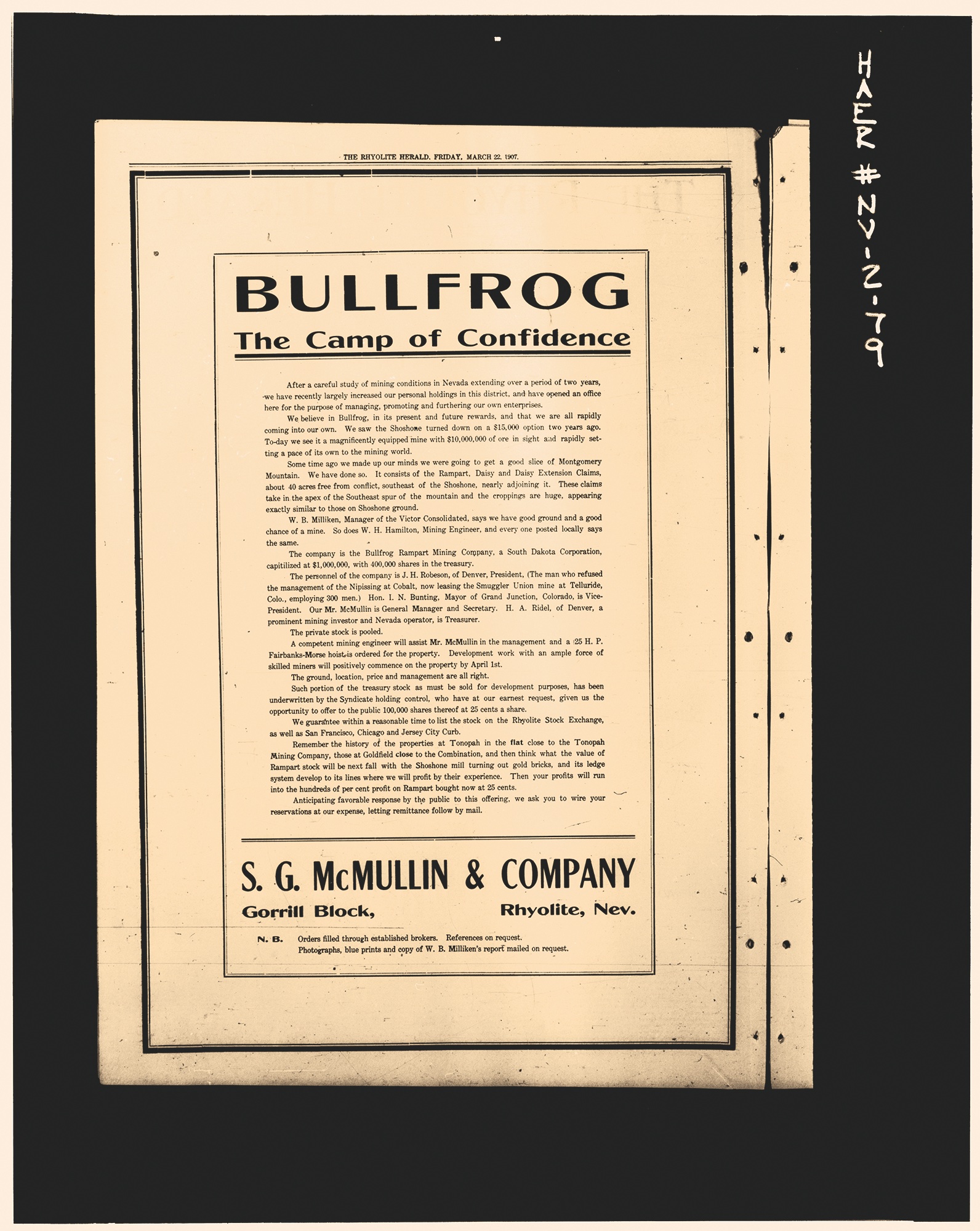

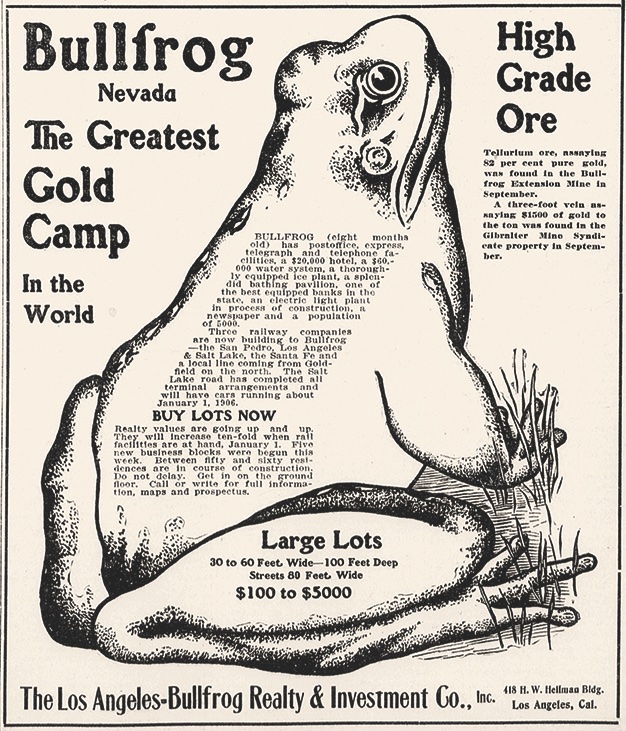

His Bullfrog Bonanza

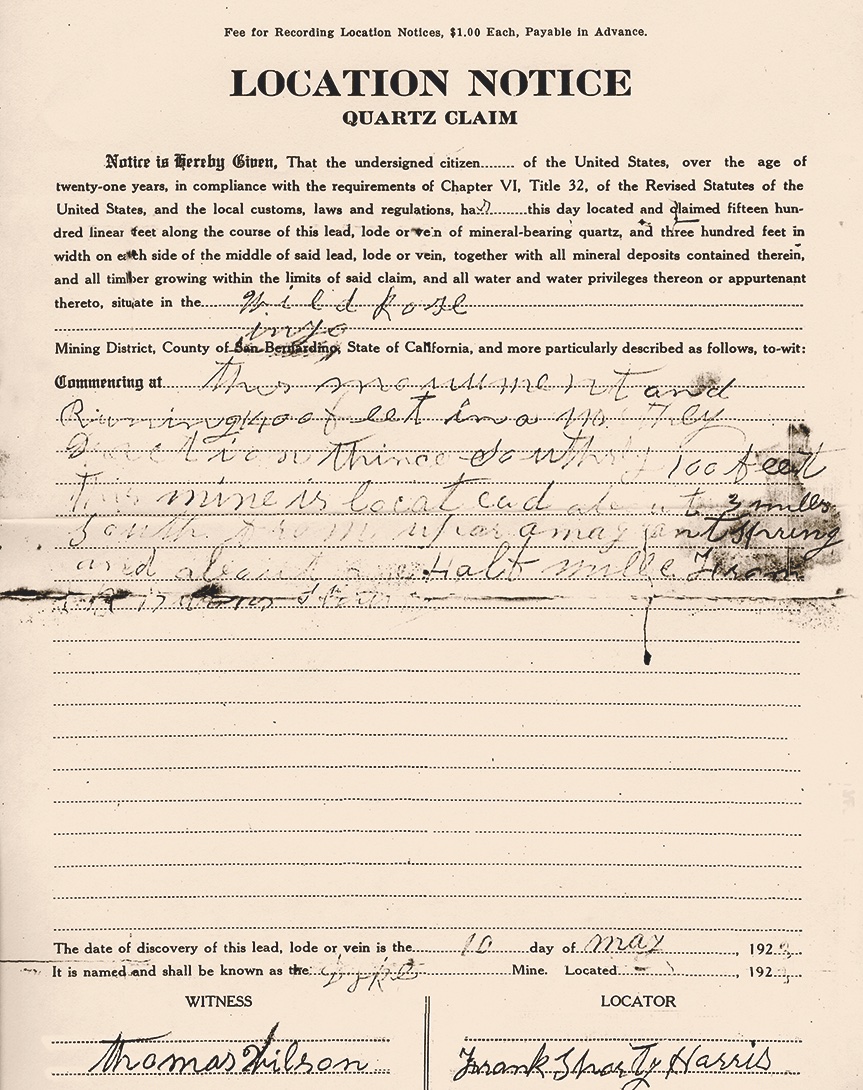

It was his burros that led Harris to his most famous mining discovery in 1904, the Bullfrog claim. He and partner Ed Cross made a camp in the Amargosa Desert of southwestern Nevada. In the morning Harris went out to round up his burros and found them feeding on the side of a mountain near the camp. A few hundred feet away he spied a ledge with some copper stains on it. After breaking a piece off with his pick, he was astonished to see chunks of gold so big that “it seemed to me the whole mountain was made of gold.” It was the greenish color of the rock that led Harris to name it the Bullfrog Mine.

Courtesy Library of Congress.

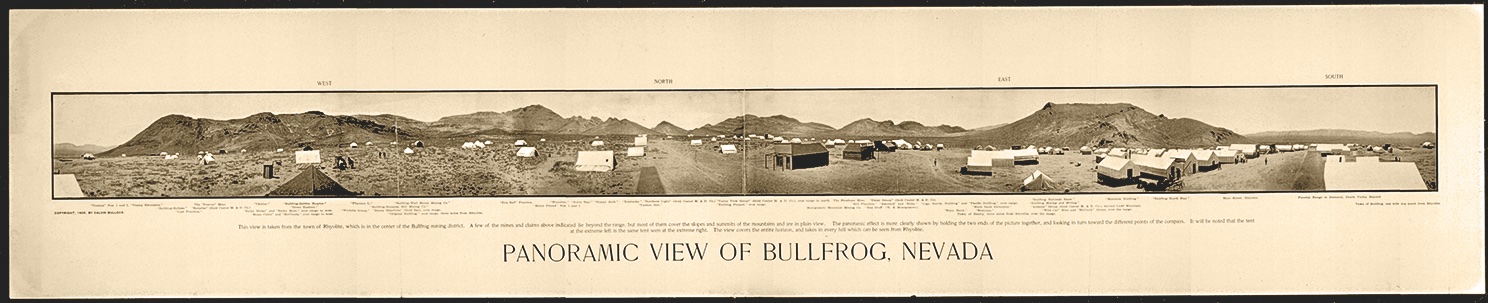

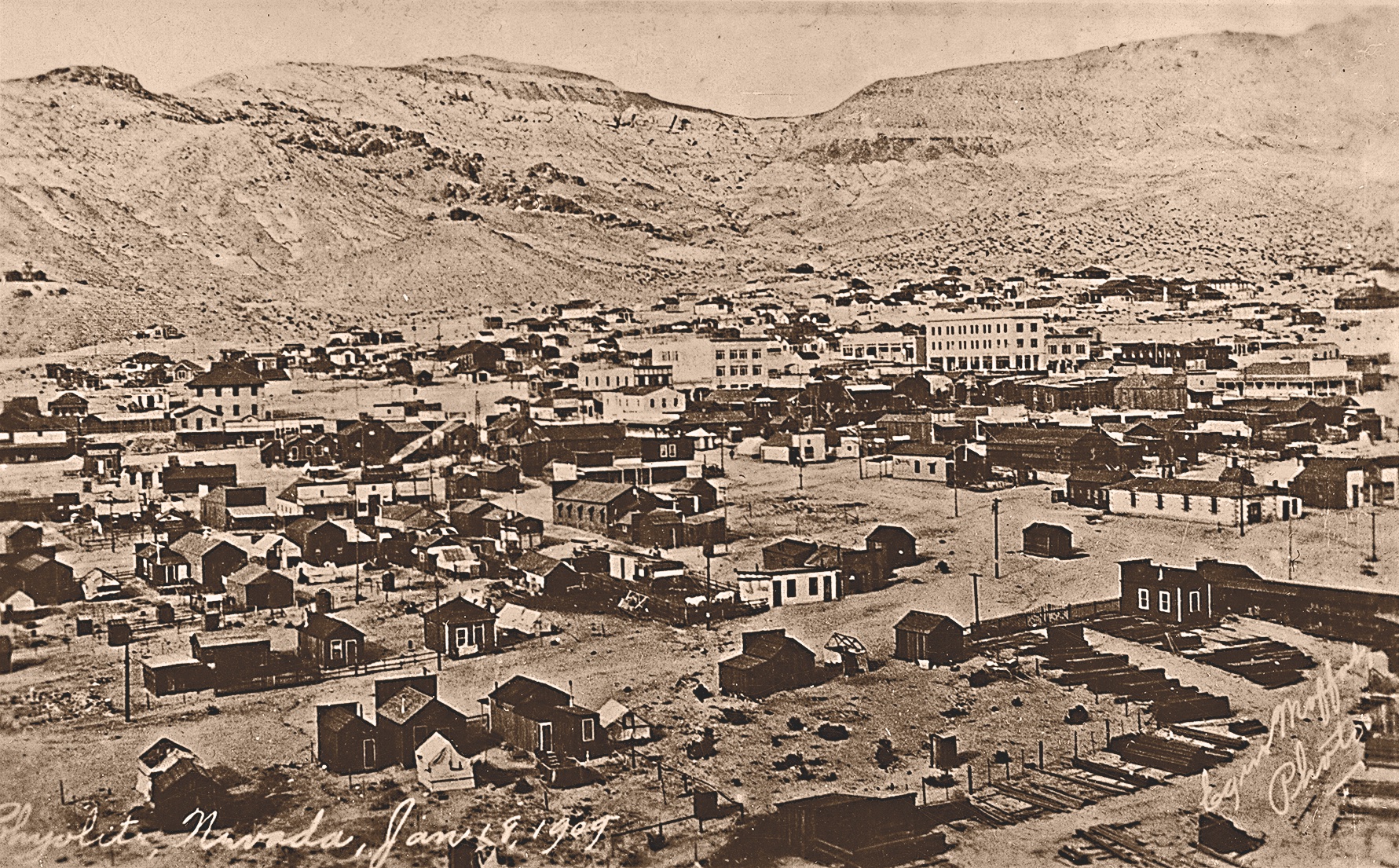

Within a few weeks thousands of people swarmed to the area of the new strike, many from nearby Goldfield. New towns were staked out: Bonanza, Bullfrog, Amargosa City and Rhyolite. Eventually, Bullfrog and Rhyolite absorbed the others, and Rhyolite became the commercial center of the district, at one point having stations for three different railroad lines. The largest and most successful mine in the district was the Montgomery-Shoshone, which eventually came to be owned by Charles Schwab.

But if it seemed Shorty Harris had finally found the claim that would make him his first million dollars, a moment of weakness had cost him that opportunity. In his own words:

“One night, when I was pretty well lit up, a man named Bryan took me to his room and put me to bed. The next morning, when I woke up, I had a bad headache and wanted more liquor. Bryan had left several bottles of whiskey on a chair beside the bed and locked the door. I helped myself and went back to sleep. That was the start of the longest jag I ever went on; it lasted six days. When I came to, Bryan showed me a bill of sale for the Bullfrog, and the price was only $25,000. I got plenty sore, but it didn’t do any good. There was my signature on the paper, and beside it, the signatures of seven witnesses and the notary’s seal. I felt a lot worse when I found out that Ed had been paid a hundred and twenty-five thousand for his half, and had lit right out for Lone Pine, where he got married.”

Whether this particular version of the circumstances surrounding the sale of the Bullfrog Mine is accurate is difficult to ascertain, since Harris never told the same story about it twice. To be sure, the Bullfrog excitement, like many other big strikes, was far less profitable for the gold extracted than it was for the sale of stocks and mining properties. Less than a decade after Harris and Cross located the Bullfrog claim, Rhyolite and Bullfrog had become ghost towns.

None of this stopped Harris from continuing his quest for the mother lode. He crossed Death Valley and soon located claims near Skidoo and a site which became his namesake, Harrisburg. The Harrisburg Mine had the potential to make him a rich man. He accepted a combination of cash and stock, but at that time company directors could vote to levy an assessment on stock, requiring the holder to pay up or lose his holdings. Such was the case with Harris, who let his stock go instead of paying the assessment.

Courtesy Library of Congress

The Final Years

Harris spent his remaining years just west of Death Valley in the desert ghost town of Ballarat, California. He lived in the abandoned schoolhouse and continued to prospect the surrounding hills, always optimistic about finding the next big strike. In 1933 a portion of the adobe schoolhouse collapsed, trapping Harris and causing him serious injury. He was discovered by friends, few of whom held out any hope of his survival, but survive he did, and after a long recovery, he was determined to return to the Panamint Mountains to prospect. He also did some work on the local roads for the county, which provided him some money for food. He and the few remaining residents of Ballarat regaled each other with stories of the old days. His best friend, Jimmy Dayton, had died in July of 1898. Dayton, a former prospector and swamper for the famed twenty-mule-team borax wagons, had been a caretaker at the Furnace Creek Ranch. The circumstances of his death were recounted several years later in one of Rhyolite’s newspapers, the Bullfrog Miner:

“Dayton had started from Furnace Creek for Daggett with an empty wagon to get supplies for the farm. He was drawn by four horses and had two horses tied to the wagon in the rear. He had a cat in a box which he was taking to a friend at Daggett and a dog followed along.

“He had been due in Daggett for two weeks, and, not arriving, Frank Tilden and a Mexican by the name of Dolph started out in search. It was midsummer and they traveled by night. Within a mile and a half of the old Eagle borax works they came upon the wagon of Dayton, which was in the road about eight miles this side of Bennett’s Hole. Around the wagon were six dead horses in harness. Dayton’s body lay under a mesquite bush near the road side and his dog sat by it as the only silent mourner. The cat in the box was also dead. They had been there 22 days.”

A survey of the place told the story. Dayton had become deranged from the heat. He had left his wagon and sought shade under the mesquite. He had died. The lead horse had drawn his companion around to the wagon to secure water or feed and became entangled with a standard projecting above the wagon body. They had stood there in a circle until they all perished. The dog had found his way to a pool of slimy water a mile and a half distant and sustained himself. He kept the vultures and coyotes away from the body of his master for 22 days.

Once, when Shorty was visited by writer and friend William Caruthers, the two men were driving through Death Valley and stopped at Dayton’s grave. Shorty walked into the brush and gathered up a handful of desert wildflowers to place on the grave, then turning to Caruthers he said, “When I die bury me beside old Jim. Above me write, ‘Here lies Shorty Harris, a single blanket jackass prospector.’”

Shorty died in his sleep on November 10, 1934. He was 78 years old. “The Short Man” was laid to rest next to Jimmy Dayton, with one of the largest crowds ever gathered in Death Valley in attendance. A miner, Wallace Campbell, wrote a poem for him:

It was 15 months after the death of Harris that the National Park Service conducted the memorial service and erected the monument which still stands today. It carries the bronze plaque which bears Shorty’s epitaph, just as he had requested. A few months before Shorty died, while recovering from his accident, William Caruthers had asked him if he would choose prospecting again if he had his life to live over.

being nearly abandoned after 1917. Courtesy the U.S. Geological Survey

“I wouldn’t change places with the President of the United States. My only regret is that I didn’t start sooner. When I go out, every time my foot touches the ground, I think before the sun goes down I’ll be worth $10,000,000.”

Caruthers reminded him that he never got his $10,000,000.

Giving Caruthers an incredulous look, Shorty replied, “Who in the hell wants $10,000,000? It’s the game, man—the game.”

Harris (right) took this photo with a friend in an unknown location in Death Valley, circa 1920s. Utah State University, Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections & Archives, Death Valley Region Photograph Collection, P0126 Box 1, Item 10

The Last Trail

He lies in state, as well becomes a knight

Of that intrepid, desert-loving clan,

Whose number soon will have

climbed the height

That marks the passing of the burro man.

The last camp made, no more

his eager feet

Shall search the dim, yet

never-ending trail,

Through winter’s chill or summer’s

thirsty heat.

His task is done; perhaps he’s

found the Grail.

That beckons all who dwell in this domain

Of rugged hills and drifting, velvet sand;

A mystic thread, for none can

speak its name—

Which gently binds us in

a phantom strand.

So stake for him a claim, six feet by four,

Where thorned mesquite and varnished

greasewood grow;

There let him sleep, beneath the

Valley floor;

And men may pass, but God will know.

Soft be his couch, beneath the golden drift

Of sunlight, shining thus since time began,

While lonely winds their

chanting voices lift

To sing a requiem for the burro man!

John H. Fillmore is a retired history teacher with a master’s in education. He has traveled and researched extensively throughout the West. In 2012 he wrote

Rainbow Chasers and Ghost Towns, a historic and contemporary view of ghost towns in the Western U.S.