— All photos Courtesy Historical Society for Southeastern New Mexico unless otherwise noted —

Long before Walter Noble Burns arrived on the scene with his Saga of Billy the Kid in the 1920s, the largely fictitious events presented in Pat Garrett’s book, An Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, were “remembered” as fact by countless old-timers who “knew” the Kid. Yet Garrett did not even write the book; his friend Ash Upson did. But who was Upson?

Upson was much more than a Southwestern mythmaker. He claimed to buddy around New York with poet Edgar Allen Poe, tutor the children of Mormon leader Brigham Young, earn an appointment as adjutant general of New Mexico Territory in 1869 and board in Silver City with Catherine Antrim and her two sons, one of whom would grow up to become the Kid.

Naturally, some doubt the writer’s connection to the Kid, among them Upson’s contemporary J.M. Miller of Roswell, who once said, “Ash’s report as being as one of the family with Billy’s mother was all a frame up. He never saw the Kid until the Lincoln County War started.”

Happy Birthday to Us

Both Upson and the Kid were born on the same day, November 23, although the Kid’s birthplace was New York, in 1859, while Upson’s was South Carolina, in 1828. We don’t have a birth certificate to confirm the Kid’s date. They both left home at a young age because of difficulties with a parent; the stepfather, in the Kid’s case, and his own father, in Upson’s case.

Upson drifted to New York where he eventually wrote for The New York Herald. He spent his early days as a journeyman, reporting for numerous newspapers and getting into various brawls. In 1862, his left eyebrow was split open. In 1864, his nose got smashed in at the “Dirty Woman’s Ranch” in the Rockies. And in 1867, someone shot him with a Smith & Wesson pocket pistol through the cheek and chest.

In 1866, Heiskell and Barbara “Ma’am” Jones found Upson wandering outside of Denver, Colorado Territory, possibly run out of town. He guided the couple and their brood down the Pecos to Seven Rivers, New Mexico Territory, where they and their children would become famous in the annals of Wild West history—Ma’am Jones for her hospitality, and her sons for their skills with a six-shooter.

After drifting back to New Mexico Territory, Upson began the Las Vegas Mail, which would eventually turn into the Las Vegas Gazette after Simeon Newman purchased it. In late 1871, Upson was the lone white on a wagon trail to Fort Stanton, where he and his friend Calvin Simpson planned to start a mercantile business. Instead, Simpson opened a bar, which Upson had no interest in running, despite being a notorious alcoholic.

— Courtesy John LeMay Collection —

The Lincoln County War

Upson left to live on Robert Casey’s family ranch, where he became the schoolteacher for those living along the Rio Hondo in Lincoln County. “My pupils are all very good in behavior except for the larger growth,” he wrote in a letter to relatives, referring to grown men, among them Lincoln County Sheriff Ham Mills, a “six footer who has killed three men and innumerable Indians in his time.”

Among the children he taught was Lily Casey, who fondly remembered Upson in her classic autobiography, My Girlhood Among Outlaws. She said of him, “A better teacher, I am sure, never lived.”

Lily’s father, Robert, was a political enemy of Lawrence G. Murphy, the big boss in Lincoln, and as a result found himself assassinated by William Wilson—a Murphy stooge. Upson was present for and wrote a newspaper account of the notorious “Double Hanging” of Wilson, who wasn’t killed the first time he was strung from the gallows. This article was a precursor of things to come, for when Upson later found himself in Roswell surveying for John Chisum, he became a war correspondent of sorts in the Lincoln County War.

During the war, Upson served as postmaster of Roswell and maintained the peace by threatening to shut down the office if violence occurred in his vicinity. As both sides needed their mail, this ploy worked. Upson even ran a private mail service for Alexander McSween whom he despised (Upson was a closet Murphy-Dolan supporter).

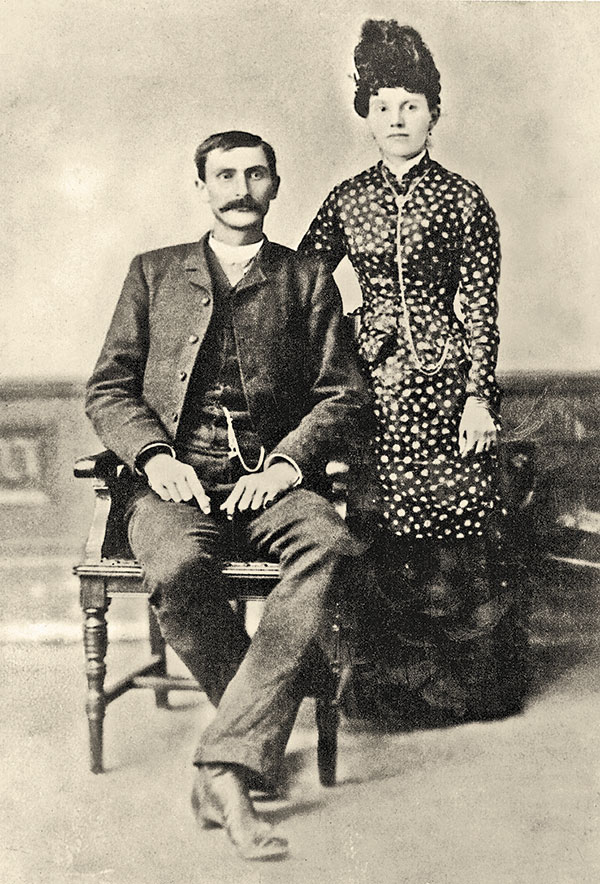

At some unknown point in history, Upson met the new sheriff-elect, Patrick Garrett, in 1879. Though most assume Roswell patriarch Capt. J.C. Lea introduced the duo, the pair may have met at a riding party. Local legend claims Garrett hunted down a party of renegade Comanches who had stolen some horses late in 1879. Upson wrote a letter, dated November 2, 1879, that states: “We followed a party of [Indians] over on the Llano Estacado the other day, whipped them, killed four Indians, got back 13 head of horses they had stolen….”

Upson and Garrett became fast friends. After Garrett gunned down the Kid at Fort Sumner on July 14, 1881, he invited Upson to live at the Garrett ranch that August.

— Courtesy Leon C. Metz Collection —

Writing Billy’s Story

When Garrett became incensed at claims that he had killed the Kid unfairly, he partnered with Upson to write a book on the topic. The result was the notoriously mistitled An Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, rife with myths and tall tales.

Since Upson knew the Kid in Roswell, and possibly in Silver City, why did he make up elaborate fabrications about him?

For one, in 1882, many of the Lincoln County War’s notorious badmen, be they political or otherwise, were still alive. Writing about them in a negative light would have been dangerous.

Second, and most important, Upson loved melodrama. The book was his chance to write the great American novel. In an 1870 letter to his niece Florence Muzzy, he wrote, “There is no sense in reading novels, and yet I have neglected my meals to finish one.”

He and Garrett reportedly argued about the book’s tone, and Garrett lamented to his former deputy James Brent that he was greatly disappointed by the book’s first draft. Though Garrett tried to reign in his ghostwriter, Upson convinced the sheriff that the melodramatic tone would sell better.

Unfortunately for Upson, Garrett, demonstrating his characteristic poor business instincts, sold the book to Charles W. Greene, editor of the Santa Fe New Mexican.

After the book’s failure to sell many copies, Upson lamented to his sister in May 1882 that, “[The book] has been bungled in the publication. The Santa Fe publishers took five months to do a month’s job, and then made a poor one. Pat F. Garrett, Sheriff of the County, who killed the ‘Kid’ and whose name appears as author of the work (though I wrote every word of it) as it would make it sell, insisted on taking it to Santa Fe, and was swindled badly in his contract.”

The story has an ironic twist. In December 1881, while Upson was working on the book, he took a trip to Toyah, Texas, with Charles Siringo, the famous cowboy detective. In Toyah, the two drunkenly rang in the New Year, but while on the trail, Upson had regaled him with his tales of the Kid, which Siringo put into his own book, A Texas Cowboy, in 1885. The book became a bestseller, largely due to the Kid’s inclusion, prompting Siringo to write future books heavily focused on the Kid, all utilizing Upson’s stories from An Authentic Life of Billy the Kid.

Dreams Unrealized

Despite the book’s failure, Upson dreamt of writing a follow-up about the Lincoln County War. He supposedly kept these writings in a small trunk he carried with him everywhere up until his death.

In 1893, Upson took a trip to visit his dying mother back East. Along the way, he got into a few “drunken tares” and ended up in jail. When he failed to return to Uvalde, where he had moved with Garrett in 1892, the Roswell Register fantastically reported, “It is feared that he now lies in an unknown grave, in a strange land and that his fate may never be known.”

Upson would have surely been pleased at the sensational attention he received.

The writer didn’t last long once he did return to Uvalde though, as he had contracted influenza. On October 6, 1894, he passed away at Garrett’s ranch.

“We buried him in the city grounds at my expense,” Garrett wrote to Upson’s sister, on November 3. “He has a trunk here and clothing. What Shall I do with them?”

The trunk Garrett spoke of was the one that contained Upson’s book about the Lincoln County War. Unfortunately, to this day, the mysterious trunk has never been found. What elaborations, fallacies and perhaps even truths that trunk contained will unfortunately never be known.

John LeMay is a past president and archivist for the Historical Society for Southeastern New Mexico in Roswell. He is the author of books Tall Tales and Half Truths of Billy the Kid, Towns of Lincoln County and Tall Tales & Half Truths of Pat Garrett. He is currently working on the first biography on Ash Upson.