— True West Archives —

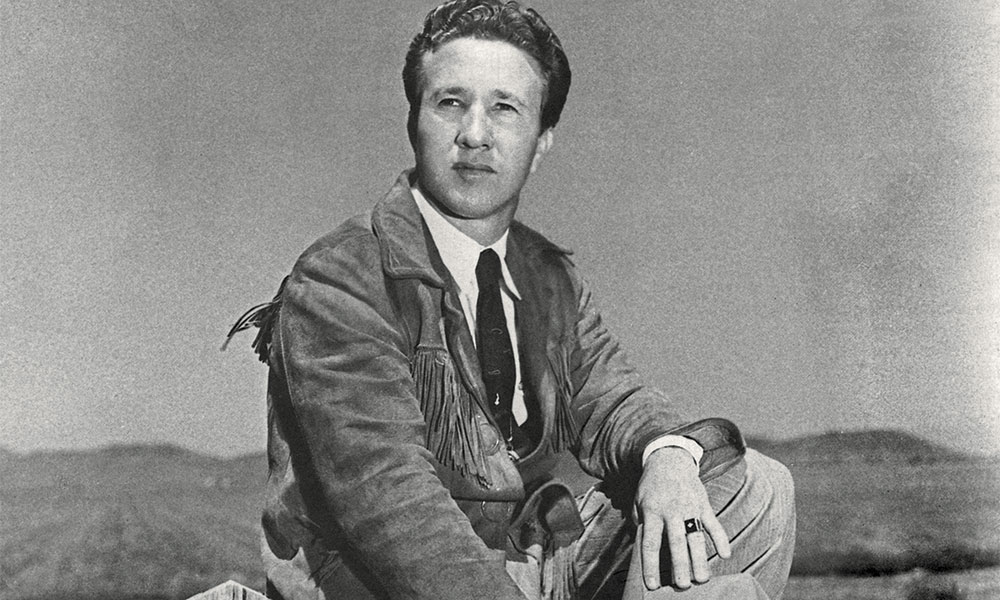

I met Marty Robbins in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, at a National Cowboy Hall of Fame event in 1979. He was there to receive the Golden Trustee Award for his Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs album. I’d seen him perform a number of times in Arizona, but this time, I got up close and personal with the celebrity; we wound up in the same hotel elevator.

To respect his space, I pulled my hat down low and stared intently at the floor. Next thing I knew, a smiling face was looking up at me.

“Hi!” he said, “I’m Marty Robbins.”

I managed a shy grin. “I know,” I said, “and I know you’re from Glendale, Arizona, and your wife’s name is Marizona.”

“How’d you know all that?”

“I used to live in Glendale, and I wrote about you in my Arizona book.”

He said, “Let’s go down to the restaurant and grab a bite to eat.”

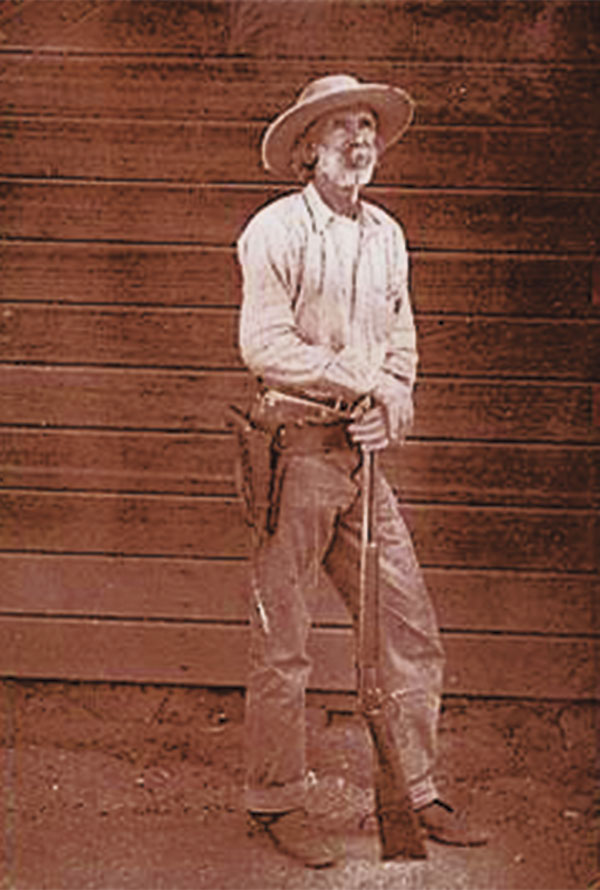

We spent the next couple of hours talking about the West. He told me how he’d come to write his Grammy-winning song, “El Paso.” He talked about his grandfather, “Texas” Bob Heckle, whose son, “Sandy” Bob, was Gail Gardner’s sidekick in his famous cowboy poem “Tying Knots in the Devil’s Tail.”

I’ll never forget the evening I met Marty Robbins.

A Rising Star

Martin David Robinson and his twin sister, Mamie, were born in Glendale, Arizona, on September 26, 1925. He grew up poor, living along the Santa Fe Railway tracks, one of nine kids.

— Courtesy Cowan’s Auctions, June 24, 2009 —

Marty’s two significant influences during his childhood were his maternal grandfather, who told him stories about the Old West, and Singing Cowboy actor Gene Autry. Marty’s fascination with the Singing Cowboys on the silver screen led Mamie to buy her twin a guitar when he was 15. That guitar would send him on a path to fortune and fame.

In 1943, Marty dropped out of high school and joined the U.S. Navy, serving in the South Pacific during WWII, where he saw action at Guadalcanal and Bougainville. During his slack time, he sat around the Quonset hut, playing his guitar for his buddies. He

also tried his hand at writing songs.

To get time off from tedious Navy chores, he also took up boxing. Weighing only 129 pounds, he fought in the lightweight class. The only fighter who knocked him down was a soldier who, in civilian life, was a professional boxer.

“During the weigh-in, the guy kept saying, ‘Watch out for my left; I’ll tell you right now, watch out for my left!’” Marty recalled.

While Marty watched for his left, the soldier threw a right that broke his nose. “I had just turned 18,” he said, “and this guy was probably close to 30 years old.”

The deception infuriated Marty. He turned up his energy a notch and knocked his opponent out of the ring. The referee declared Marty the winner.

After receiving his discharge on February 25, 1946, Marty headed back to Phoenix, where he took a job hauling ice around town, for $1 an hour. He did a lot of job-hopping, telling his friends he was looking to move up the work ladder, but he later admitted, “I was really looking for a way to get out of work and still make a living.”

In 1947, Ole Dame Fortune lent a helping hand. As a regular at Vern and Don’s, a bar on East Van Buren Street in Phoenix, Marty made the acquaintance of Frankie Starr, the featured artist in the bar’s band. One evening, Starr came over and said his guitar player was missing and asked if Marty could fill in. “I couldn’t play very well, but I could play better than Frankie,” Marty said.

The gig lasted three hours. Afterwards, Starr handed Marty $10. For a guy making $1 an hour hauling brick, Marty thought he’d been overpaid. But Starr told him that was union scale.

Marty played with the band the next two nights and pocketed $30. When that missing guitar player ended up leaving town, Marty became the band’s lead guitar player. At last, he was making money doing something he loved.

His next break came one night when Starr was sick and asked Marty to fill in. Marty told me that he felt so shy and self-conscious, he couldn’t even look at the audience. He got behind the microphone, stared at the floor and performed his first song on stage, Eddy Arnold’s, “Many Tears Ago.”

Marty said the audience liked him, but he added modestly, “I think they just felt sorry for me.”

Starr taught Marty a lot about engaging with an audience. This interaction style would later make Marty one of Country music’s most beloved performers. During his Grand Ole Opry years, when most entertainers made a hasty exit, Marty never left the stage area until everyone got a chance to say hello, take a photo or ask for an autograph. His fans called themselves Marty’s Army.

Starr was also responsible for Marty landing his first gig on the radio. The two began singing on KTYL radio in Mesa. The station had a large window in front, and folks would pull up outside and watch the show.

Marty was still taking a lot of needling from his blue-collar-worker brothers about making a living playing music; they kept advising him to get a “real job.”

One of these friends, though, Harry Tolmachoff, gave the singer the idea to shorten his name to Marty Robbins.

Financially, Marty was making enough for a single guy to scrape by, but by September 27, 1948, Marty had taken a bride, Marizona Baldwin. He had met her in an ice cream parlor in Glendale, soon after he got out of the Navy. The couple married in Parker and honeymooned across the Colorado River in Earp, California.

The next couple of years, Marty worked gigs wherever he could find them. Once he saved up enough money, he drove to California in the hopes of securing a contract with Capitol Records. But they weren’t interested, so he returned to Arizona and continued playing the bars.

Times were tough. The couple now had an infant son, Ronald, which made Marty more determined to make it in the music business. He assured Marizona he would join the Grand Ole Opry and make records.

In late 1949, Marty became the lead singer at Vern and Don’s when Starr left for Texas. With Floyd Lanning on lead guitar and Jimmy Farmer on the steel, the K-Bar Boys were packing ’em in. People waited outside for an open seat in case someone left.

Television came to Phoenix in December 1949 when KPHO began broadcasting from the Westward Ho Hotel. It was the only TV station between El Paso, Texas, and San Diego, California.

By 1950, Marty had left a successful KTYL radio gig, a half-hour morning show, to star in Chuck Wagon Time. When the station manager needed to fill a 15-minute slot, he offered Marty the job. A timid Marty, who had returned to his work in radio, initially declined. But upon learning that his radio show depended upon him taking the TV spot, he changed his mind. The show, Western Caravan, turned out to be a great success. “The viewers liked the show,” he said, “and good things began to happen.”

His big break came when Jimmy Dickens appeared as a guest on Marty’s show. After hearing Marty perform, an impressed Dickens returned to California and told the boys at Columbia Records to send someone to Phoenix to check out Marty. In 1951, Columbia signed Marty to a record contract.

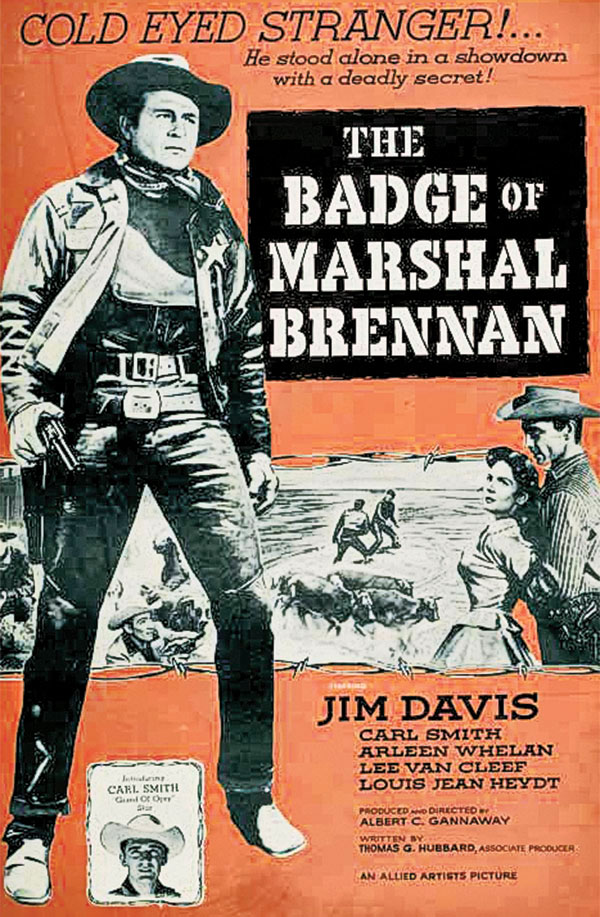

— Raiders of Old California Courtesy Republic Pictures; The Badge of Marshal Brennan courtesy Allied Artists —

The Columbia Years

One year after signing a contract with Columbia, Marty Robbins sang a song that rose to the number one spot on the charts, “I’ll Go On Alone.”

Harry Stone of KPHO and Fred Rose of Acuff-Rose played a big part in getting Marty to Nashville, Tennessee, and on to the Grand Ole Opry, where the singer became an official member of the prestigious community.

Marty’s first big hit came in 1956, “Singing the Blues.” The song earned Marty a Triple Crown award and established him as one of Nashville’s hottest young singers.

Believing he needed a different Country sound, Columbia sent Marty to New York to record with strings and arrangements. The result was “A White Sport Coat (and a Pink Carnation),” which sold more than a million copies. Both songs climbed the Pop charts and hit number one on Country-Western charts.

Marty sang in a wonderful, rich mellifluous voice, with perfect pitch and a versatile range that allowed him to perform just about any kind of music. He recorded Country, Rockabilly, Pop, Western and Calypso. Remembering his WWII days in the South Pacific, he even recorded an album of Hawaiian songs. He was truly a renaissance man, one of Country music’s few multi-talented artists.

But Marty’s roots were in Country and Western music. In 1959, he returned to Nashville, Tennessee, to record Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs. One of the album songs, “El Paso,” won the coveted Grammy, becoming the first Country-Western song to win such recognition. The song went to number one on both Pop and Country charts, marking the beginning of bridging the gap between the two music fields.

That same year, Marty’s daughter Janet was born. Both she and Ronnie inherited their dad’s musical talent and went on to become successful Country music singers.

Marty said he got the idea for “El Paso” while driving through the border city in 1955, on his way to a family gathering in Texas. Two years later, passing through the city again, the song took shape in his mind as he visualized a Western melodrama about a cowboy who fell in love with a Mexican girl who danced in a place called Rosa’s Cantina. By the time he reached Phoenix, Arizona, 10 hours later, he was ready to write. The song took only a few minutes to compose.

Rosa’s Cantina was inspired by a real place in Glendale, where Marty hung out as a kid. Unknown to him when he wrote the song, the Texas town of El Paso also had a saloon named Rosa’s Cantina.

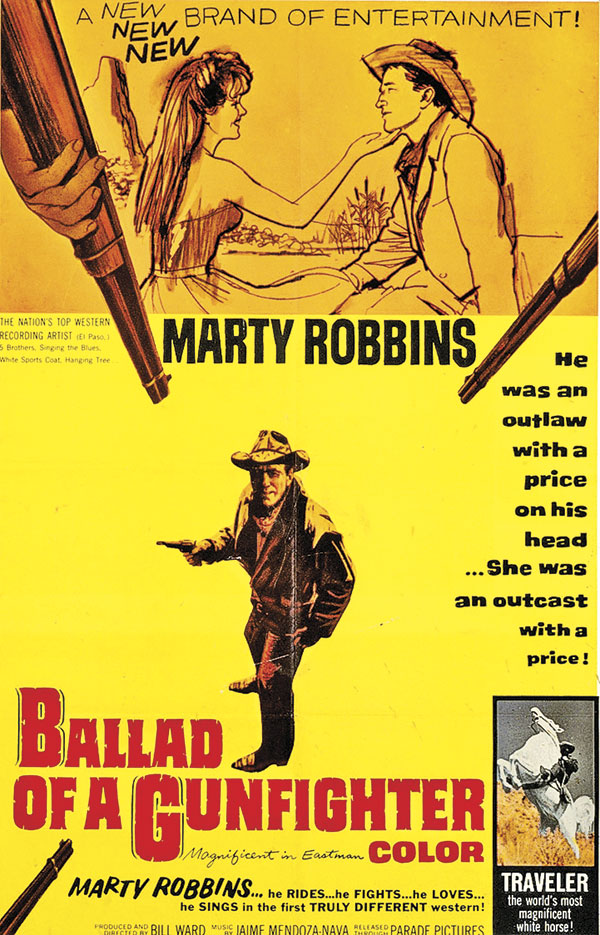

— Courtesy Parade Releasing Organization —

Movies, Horses, and Cars

While Marty was singing music for Columbia, he also appeared in six Western feature films. He worked on television in three series, The Drifter, The Marty Robbins Show and Marty Robbins Spotlight. He also owned a couple of publishing companies, a record label and wrote a Western novel, The Small Man.

The Academy of Country Music voted Marty “Man of the Decade” for 1960-1970. He was a member of the national Songwriters Hall of Fame and the first member of the Arizona Songwriters Hall of Fame. In October 1982, Marty was voted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. That same year, he appeared with Clint Eastwood in Honkytonk Man.

Marty’s two hobbies were horses and cars. His love for horses shone through when he sang “The Strawberry Roan;” “I know there are ponies that I cannot ride. There’s some of them left; they haven’t all died.” His lifelong passion for auto racing began on the small dirt tracks, yet Marty proved good enough to compete in the NASCAR circuit against greats Richard Petty and Bobby Allison. Marty finished six times in the top 10. He ran his last race just a month before his death.

Marty had a long history of heart trouble, starting with a massive heart attack in 1969 (one went undiagnosed and untreated the previous year). In 1970, he became one of the first persons to undergo a triple bypass operation, which added several years to his life. He suffered a minor attack in 1981 and in December 1982, after returning home from his final concert for the year, he suffered a massive attack. For six days after his quadruple bypass surgery, Marty struggled to live. But the damage had been too great. After his kidneys and liver failed, he died on December 8.

Many Tears Ago

Marty recorded 18 number one hits, but he is still best remembered for “El Paso.” The folks in that west Texas town were so grateful to the singer for his song, they installed a plaque honoring him at the city airport.

On the day of Marty’s death, clouds gathered overly a normally dry El Paso. A light rain began to fall. I believe those raindrops were tears being shed over the passing of one of the world’s greatest Country music legends.

Marshall Trimble is Arizona’s official historian and vice president of the Wild West History Association. His latest book is Arizona Outlaws and Lawmen. He gives a big “Thanks” go Arizona music historian John Dixon for his advice and suggestions in writing this article.