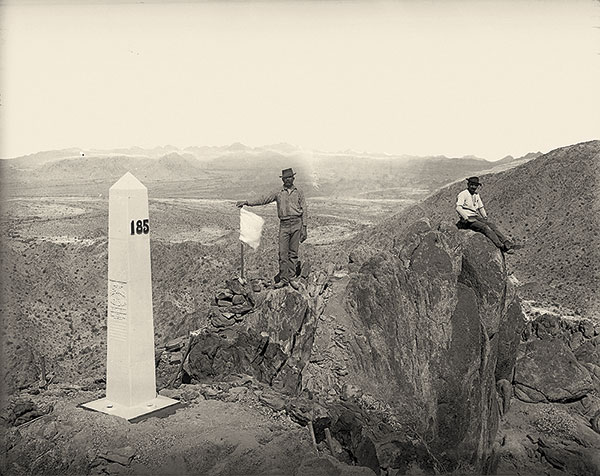

— Courtesy Museum of New Mexico —

Two American presidents, George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, began their lives as surveyors, a skill in short supply when the U.S. tried to draw its boundary with Mexico following the victory in 1848. The 1850 survey party that walked in their footsteps fully understood that the future of the U.S. and Mexico hung on them successfully mapping the nebulous border.

Their service was marred by a poorly worded treaty that started the boundary from the village of El Paso in Texas, resulting in the American surveyors drawing wildly inaccurate maps. Showing El Paso eight miles north of its actual location, the maps led to confusion and conflict over the U.S.-Mexico border in this remote corner of the continent.

The full story offers up backroom dealings, a growing conflict between free and slave states prior to the Civil War, the flawed man behind the name on the map and the bargain that finally ousted a dictator who had not been brought down by losing a war.

The Mexican-American War, like Vietnam more than a century later, was not uniformly popular in the United States. Northerners suspected the real aim of the war was to extend slavery to the west. Southerners welcomed Texas as a slave state and were ready to take on more territory, including Cuba and large parts of Mexico.

In 1848, after the end of the war, the two countries negotiated the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in which Mexico ceded a vast territory to the United States. In exchange, the U.S. paid Mexico $15 million and assumed $3.25 million in claims against the Mexicans. This is the treaty that resulted in the inaccurate placement of El Paso and thus an ill-defined border between the two nations.

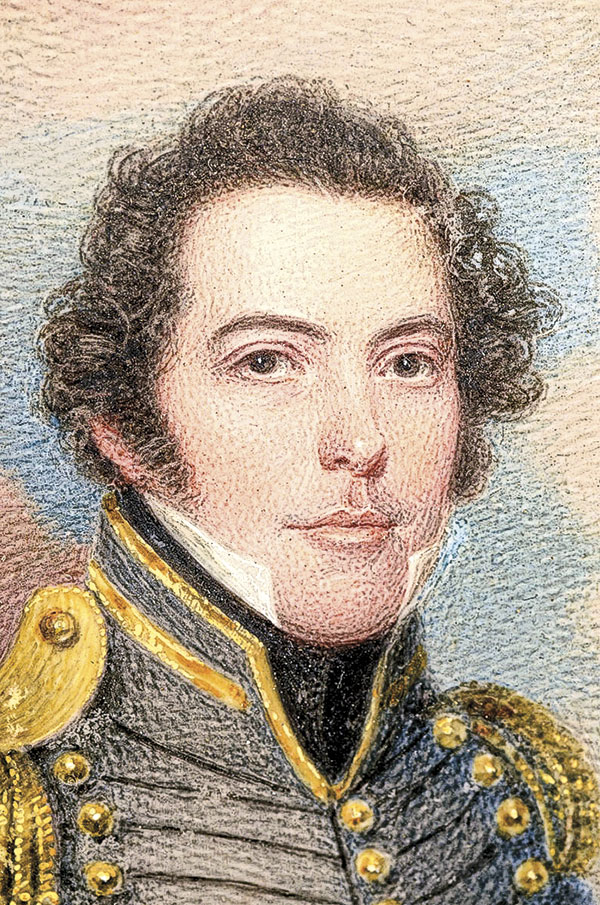

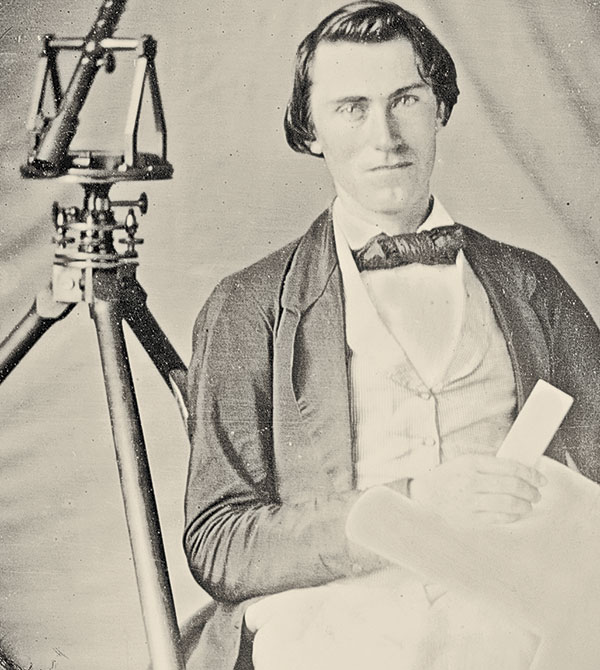

— Descended from the Estate of Mary Louise “Lou” Kidder Gadsden, Charleston, South Carolina —

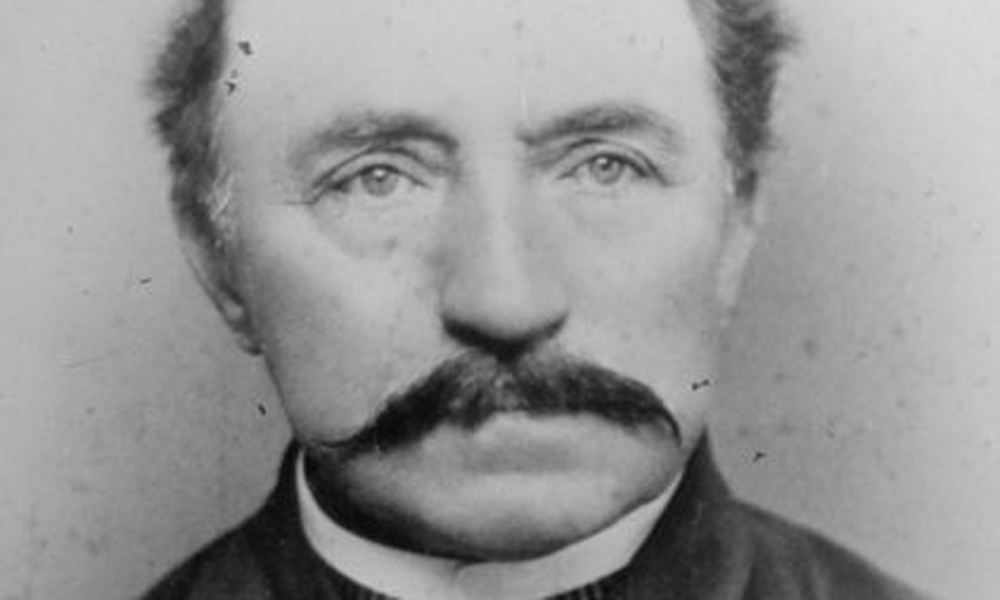

The Man Behind the Name

While the survey party worked on its mission, which would be completed in 1855, the newly inaugurated U.S. President Franklin Pierce appointed James Gadsden as ambassador to Mexico in 1853.

A native of South Carolina, a Yale graduate and a soldier under Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812, Gadsden owned slaves on his Florida plantation. He opposed the admission of California as a free state and, with the help of his senator cousin Edward Holmes, attempted to divide California in half, making the southern section a slave state.

After that effort failed, Gadsden led 1,200 petitioners to southern California to establish a slave-friendly colony with at least 2,000 slaves. When he was appointed Mexico’s ambassador, Gadsden had his best opportunity to advance slavery into the frontier.

Gadsden left for Mexico City with the task of negotiating a new border. He reported to Washington, D.C., that Mexico was willing to sell territory: “This is a government of plunder and necessity.”

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Not long after his arrival, Gadsden was joined by Christopher Ward, who recited five options presented by the U.S., the largest of which was the purchase of Baja California and parts of northern Mexico for $50 million. On his own, Ward added that Gadsden should also address claims made by the Garay settlement, which Ward owned, along with other investors. Gadsden was infuriated when he later learned of Ward’s deception.

In September, Gadsden met with Antonio López de Santa Anna, the same Santa Anna of Alamo infamy and the president who had led his country to defeat in the Mexican-American War. The toehold of “His Most Serene Highness” on power was weak. He needed money to maintain the Mexican army and put down the opposition. Santa Anna, however, rejected the $50 million offer.

After several meetings, Santa Anna and Gadsden agreed that the U.S. would purchase roughly 45,000 square miles for $15 million. Gadsden also agreed to assume the claims of the Garay settlement and to try to control the cross-border raids of American Indians into Mexico. From the American side, the most important gain from the treaty was the opening of a southern path for a railroad.

The Last Straw

The Senate had to confirm Gadsden’s agreement. Northerners were suspicious of the motives to extend slavery, at a time when the conflict between free and slave forces was erupting in Kansas Territory. Some Southerners were disappointed by the limited scope of the treaty, as they had hoped the agreement would have included a port on the Gulf of California.

During the Senate proceedings, a copy of the treaty was ordered privately printed for the members’ examination. Within days, however, a copy also appeared in a daily newspaper. An outraged Senate formed an investigative committee to “ascertain the manner and means” of the leak; the senators never found the culprit.

As the public weighed in on both sides of the issue, the Senate took a first vote on April 17, defeating the proposal 27 to 18. After intense bargaining, the Senate amended the treaty, removing 9,000 square miles and reducing the price to $10 million; this was approved on a 33 to 28 vote.

Opposed to these amendments, Gadsden expressed that talks could be delayed until Santa Anna was overthrown. Yet President Pierce told Gadsden the amended treaty was the best he could expect under the circumstances.

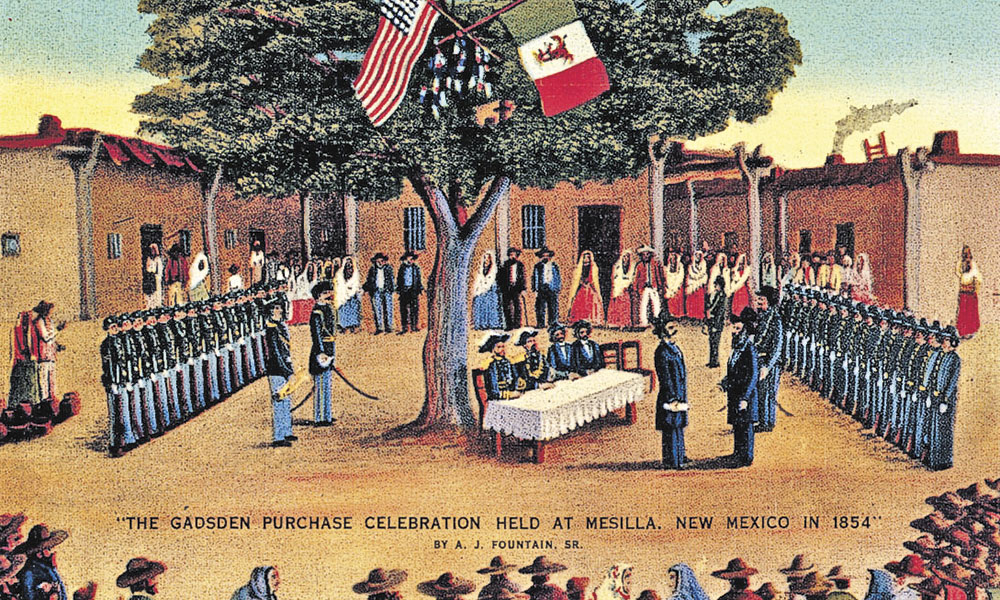

Under pressure, Santa Anna agreed to the altered terms. The treaty he signed on May 31, 1854, was the last straw for the Mexican people. They overthrew Santa Anna, who escaped into exile. He was tried in absentia for treason.

During a later period of exile, he ended up on Staten Island in New York where he came up with a product Americans soon would be chewing over quite a bit. He attempted to make artificial rubber out of a plant called chicle. His experiment failed,

but someone noticed the material could be chewed. Santa Anna and other investors had developed the first chewing gum in America, including

the gum still called Chiclets.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Arizona’s Entry

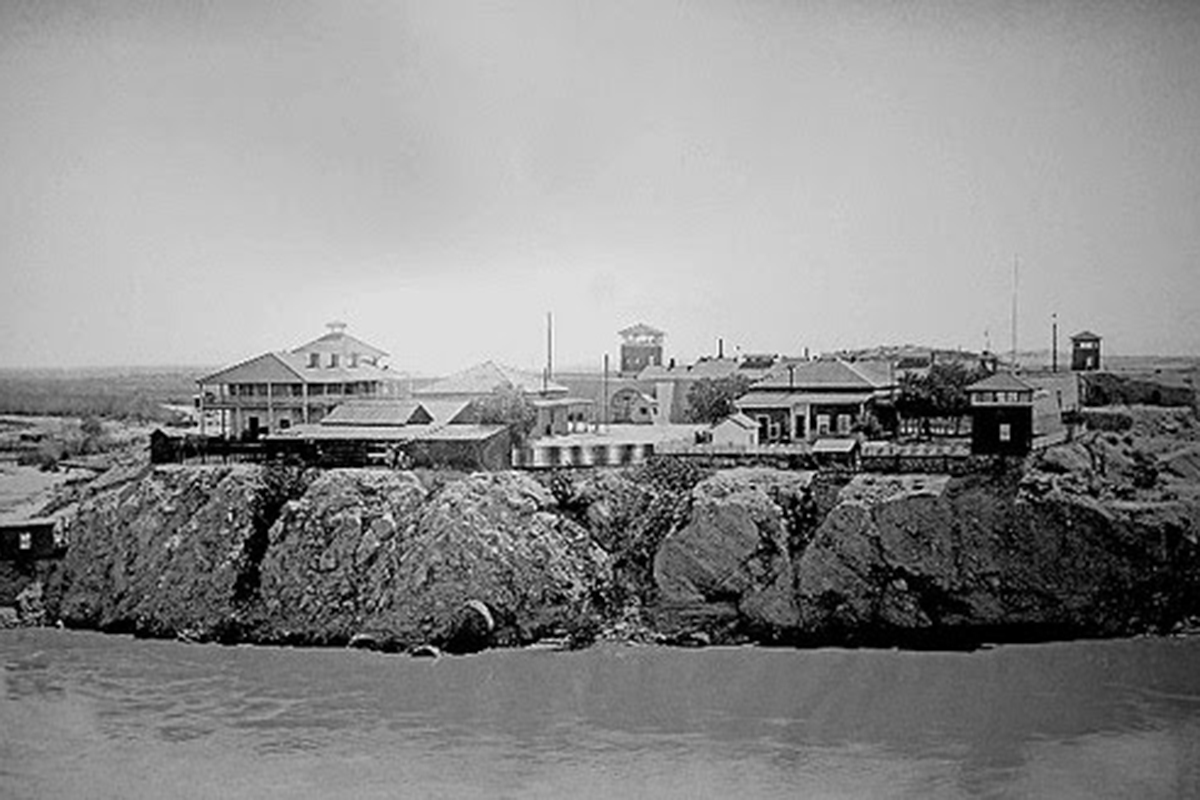

With Santa Anna out of the picture and a defined U.S.-Mexico border, American settlers in Arizona began asking for territorial status as early as 1856. One name unsuccessfully promoted for the region was Gadsonia.

After Gadsden died in 1858, several hundreds of his slaves were sold to other masters. Southern interests turned toward Cuba, resulting in a failed attempt to force Spain to sell the territory for $100 million or lose it in a war. The southern transcontinental railroad route to the Pacific Ocean was not completed until the 1880s, well after the northern route was running.

— True West Archives —

In the end, was the Gadsden Purchase of 33 cents per acre a bargain? Ask Tucson, a town occupied at that time by native tribes, descendants of Spanish explorers and Mexicans, which entered the nation as the largest Arizona city within the boundary. The U.S. had won big. Two-fifths of what was then Mexico is territory now comprising most of Arizona, New Mexico, California, Colorado, Utah and Nevada.

Greg Bailey is a journalist, playwright and former attorney based in St. Louis, Missouri. His work has been published in The Economist, American Heritage and Time.