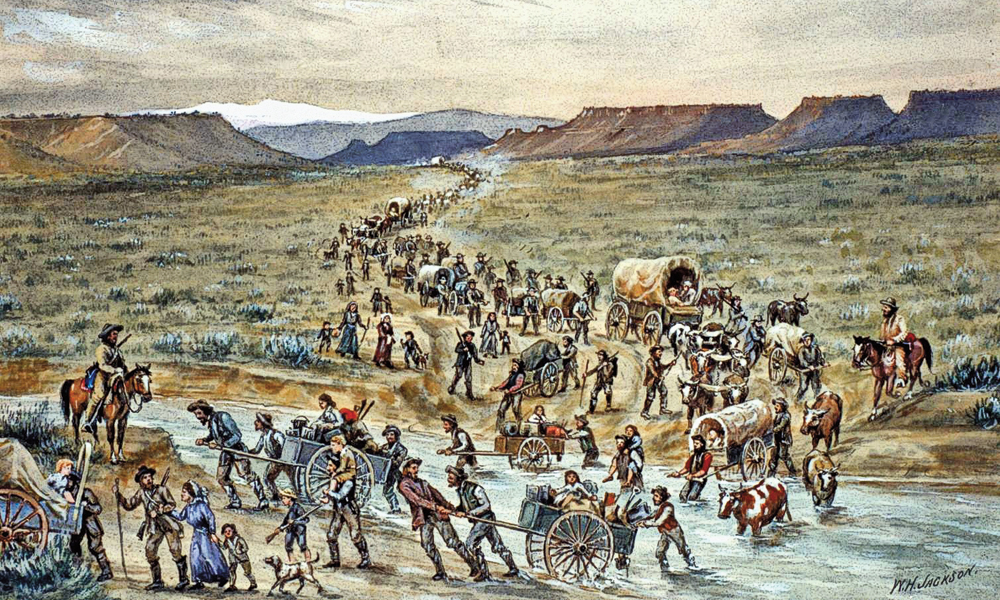

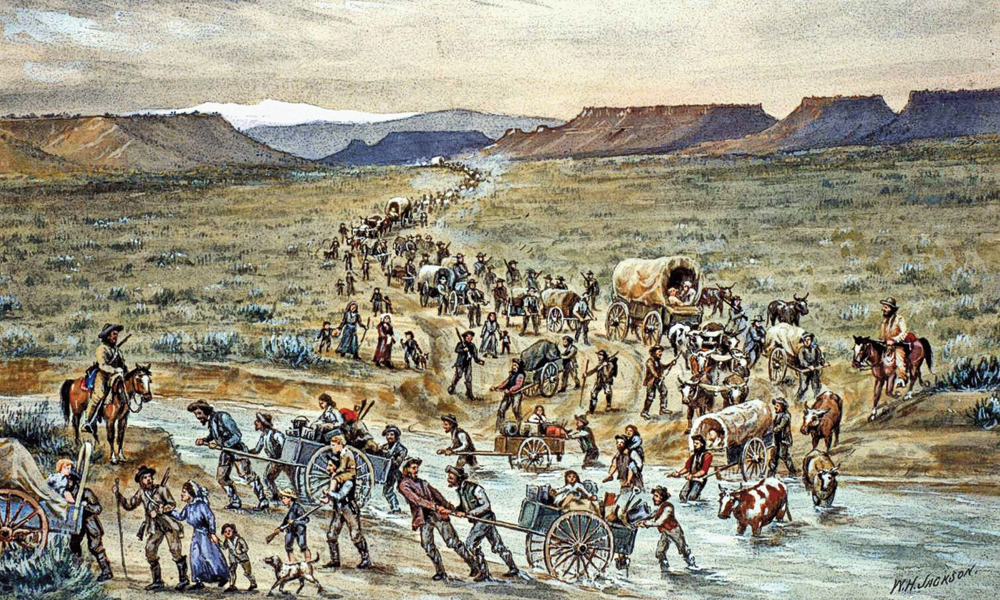

When the Mormons, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, abandoned Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1846, they made a pledge to gather all members to their new Zion. The journey took them to the Missouri River that first year, and on to Great Salt Lake City, which they founded in 1847. Over the next few years church members traveled in overland wagon trains to new homes at the base of the Wasatch Mountain range.

As had been the case almost from the inception of the church by Joseph Smith, missionaries also took the word of their church to other areas, notably to England and Scandinavia. By the early 1850s church converts in England began booking passage on ships that brought them to St. Louis, Missouri, for journeys up the Mississippi and Missouri River to jumping-off locations to travel westward by wagon.

Many of these travelers used provisions of a Mormon program instituted in 1849 when the church allocated $5,000 to create the Perpetual Emigration Fund (PEF). The goal was to pay for the transportation costs for the converts to help them reach Utah. Once there, they would repay what had been expended in their behalf, so the fund would continue into perpetuity.

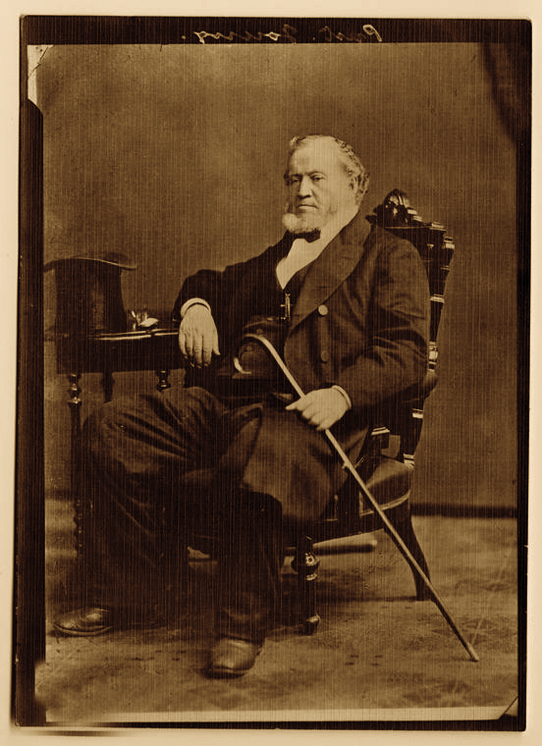

By 1855, however, the church and its PEF were struggling financially, which might have led to church President Brigham Young to resurrect what he called an “old plan—to make hand-carts, and let the emigration foot it, and draw upon [the handcarts] the necessary supplies, having a cow or two for every ten. They can come just as quick, if not quicker, and much cheaper—can start earlier and escape the prevailing sickness which annually lays so many of our brethren in the dust. A great majority of them walk now, even with the teams which are provided.”

Young decided that most immigrants from England and Scandinavia could travel under their own power, pushing and pulling small two-wheeled carts to carry their meager possessions—just 15 to 17 pounds of goods per person.

With deep faith, unyielding determination, little money, and not much information that would indicate how hard a journey by handcart would be, the converts set out. In the late spring of 1856 they departed from Liverpool on a series of ships that brought them to Boston and New York (and later to Philadelphia), where they boarded trains for the first leg of their journey across America.

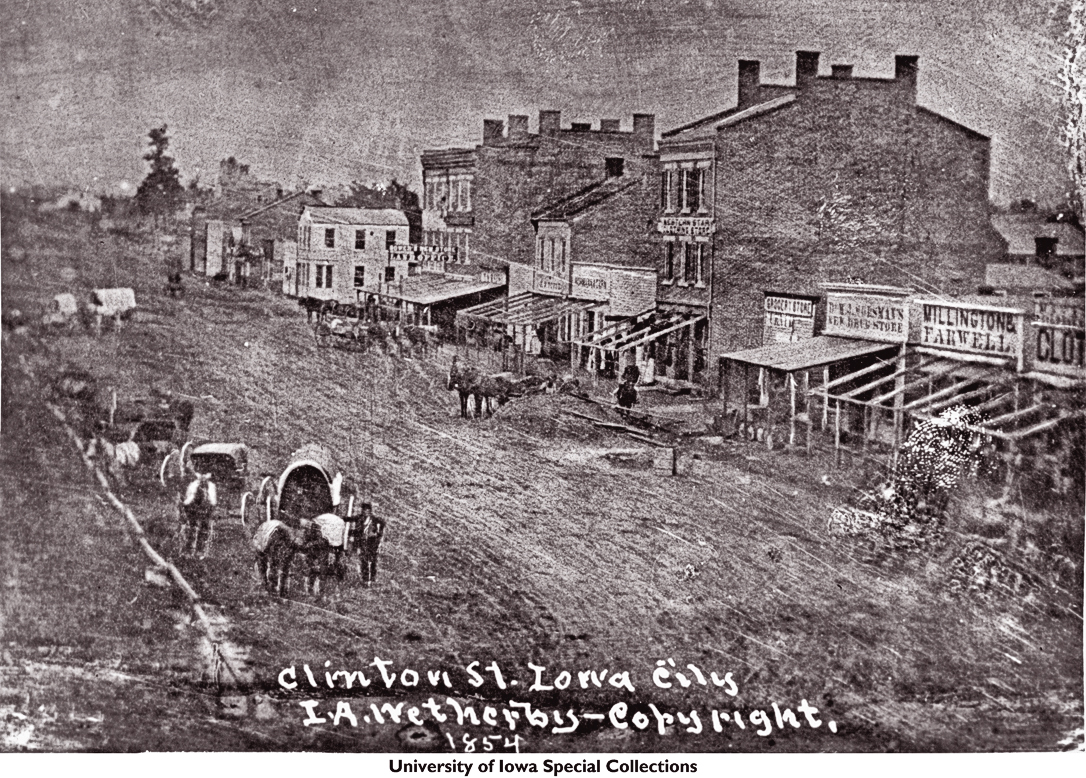

The Trail Begins in Iowa City

Handcart travel would start at Iowa City, Iowa, where a base camp was established. Mormon leaders arranged for the construction of the carts, expecting to have plenty built and ready for use when the first companies arrived.

These Mormons now faced several weeks of grueling travel pushing and pulling what later Danish handcart Capt. John A. Ahmanson called “tohjulede Menneskepiner.” Although this has been translated as “two-wheeled man-tormentors” by some, or “two-wheeled human sorrows” by others, historian Will Bagley says it “might be bettered rendered as ‘two-wheeled torture devices.’”

The migration began on June 9, 1856, when Capt. Edmund Ellsworth and 274 people pushing and pulling 55 handcarts departed camp at Iowa City. Two days later Capt. Daniel D. McArthur’s company of 220 people rolled more than 40 handcarts away from Iowa City.

The third handcart company, led by Capt. Edward Bunker, would follow on June 28. Two additional companies led by James Willie and Edward Martin journeyed west that year, starting out so late that they would face severe trials in Wyoming when winter weather caught them still on the trail. Another five companies would eventually follow the trail, the final one making the trip in 1860.

The first major stopping point for the companies was beside the Missouri River in Florence, Nebraska. This location, Winter Quarters, had been the wintering place for the Mormon pioneers who camped and built small cabins here in the winter of 1846-’47. They were not prepared, however, and many became ill and died. They are buried in a cemetery in the city, and across the street today is a Mormon Trail Center where you can learn about the early migration of this religious group and find directions to other Mormon sites in the community.

Leaving Florence the route heads west to Fremont, Nebraska, and then extends along the Platte River the breadth of Nebraska. Follow U.S. 30 to stay closest to the route. As you drive imagine making every mile step-by-step pushing and pulling a small cart containing everything you own plus possibly one or more of your children, or an elderly, ill or injured friend or relative.

The handcart companies followed a well-established trail. The travel was difficult as they lacked adequate food supplies, wore out their shoes and faced unpredictable weather. They had deaths in each company, from disease and accidents. When crossing Nebraska, they often encountered tremendous herds of buffalo. The big animals were difficult for the Mormons to hunt. The buffalo herds sometimes swept up cattle that were part of the handcart company, but they certainly left behind one important commodity: buffalo chips that could be gathered during the day and used for campfires at night.

On to Wyoming

The second major provisioning point along the trail was at Fort Laramie, where the companies usually obtained at least a few supplies, and depending on the year and time of travel, they may have rested for a day or two. The Willie and Martin companies were very late starting out in 1856 and neither lingered very long at Fort Laramie, maybe only a few hours—which is what you will need at minimum today to fully explore this frontier fort.

From Fort Laramie the route follows the North Platte River to Casper (take U.S. 26 and I-25). Points of interest along the way include “Rock in the Glen” in Glenrock, Ayers Natural Bridge and the Reshaw Bridge in Evansville. In Casper visit Fort Casper and the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center, which has a theater show that focuses on one of the families that traveled with Martin’s company in 1856, and became stranded west of Casper by harsh storms.

Our route follows them out of Casper on county roads, which in many places overlay or directly parallel the Mormon Pioneer Trail (get route information at the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center). You can also take Wyoming State Highway 220 west to Independence Rock and Devils Gate. If you stick closer to the handcart trail by following county roads, you will see Avenue of Rocks, and pass the historic site at Horse Creek where the Martin Company finally encountered rescue wagons (this was also a later Pony Express station site). You will connect to Highway 220 just east of Independence Rock.

Follow the highway on west to the Handcart Ranch. Here you can visit an interpretive center in the old Sun Ranch home, and visit a replica of Seminoe’s Fort, which the Martin Company used for brief refuge before they moved to a small cove, now called Martin’s Cove, west of the Devils Gate. They would remain here for several days. Well over a hundred people in both the Willie and Martin companies died between the crossing of the North Platte at Casper and this area along the Sweetwater River.

From the Handcart Ranch, where you can push and pull your own handcart along the trail for a few miles, travel to Muddy Gap and then turn north on U.S. 287. A new visitors’ center is now open at Sixth Crossing, beside the Sweetwater River. This center focuses on the difficulties of Willie’s company and follows the journey of my own children’s ancestors: Sarah and Thomas Moulton, who left England in May 1856 with their eight children. The youngest was Charles Moulton, born on the ship after they sailed from England. He is my children’s great-great grandfather. (I married into the Moulton clan a few decades ago.)

Trail use is heavy in this area from Mormon groups who come to experience the landscape and route for themselves, but it is accessible to all, mainly crossing Bureau of Land Management land.

South Pass beckons, and the route turns west along Wyoming State Highway 28, going over the pass and toward the Green River. Remain on Highway 28 when you drive through Farson, Wyoming (don’t blink or you’ll miss it). After crossing the Green River, take U.S. 189 and I-80 to Fort Bridger, another critical provisioning point for the handcart companies, which was established by Jim Bridger in 1842, but was under the control of the Mormon Church at the time of the handcart migration. From Fort Bridger continue following the trail route on I-80 west to Salt Lake City.

Over the Wasatch Mountains to Zion

The first and second handcart companies traveled very closely together all across the plains, and arrived in Great Salt Lake City together on September 26, 1856. President Brigham Young and H. C. Kimball “escorted by the minute men and a company of Lancers,” and followed by general citizens who walked or took horse-drawn vehicles, met them as they neared the city. The Nauvoo Brass Band and Capt. Ballo’s band heralded the handcart travelers’ arrival. Charles M. Treseder described the first carts rolling into the city: “folks came running from every quarter to get a glimpse of the long-looked-for hand-carts.”

Treseder later wrote: “I shall never forget the feeling that ran through my whole system as I caught the first sight of them. The first hand-cart was drawn by a man and his wife, they had a little flag on it, on which were the words: ‘Our President—may the unity of the Saints ever show the wisdom of his counsels.’”

Bunker’s third company arrived in Great Salt Lake City at 6 p.m. on October 2 to almost no fanfare. The fourth and fifth companies would not straggle in until weeks later. The Willie Company reached Salt Lake on November 9, while Martin’s Company, of which 135 to 170 people died, did not arrive until November 30. Everyone in those last two companies of 1856 suffered terribly from the difficulties they had faced: lack of food and proper clothing, freezing weather, deep snows.

Despite the disastrous crossings of Willie and Martin—the worst single disasters encountered by any overland travelers—the church continued supporting the handcart scheme. From 1857 until 1860 another five companies of people from the British Isles and the Scandinavian countries trudged the trail with their two-wheeled carts. More would die, but the majority safely reached Utah.

Candy Moulton traveled with the Mormon Trail Sesquicentennial Wagon Train in 1997, pushing and pulling a handcart for part of the journey. She is working on a book about the handcart migration.