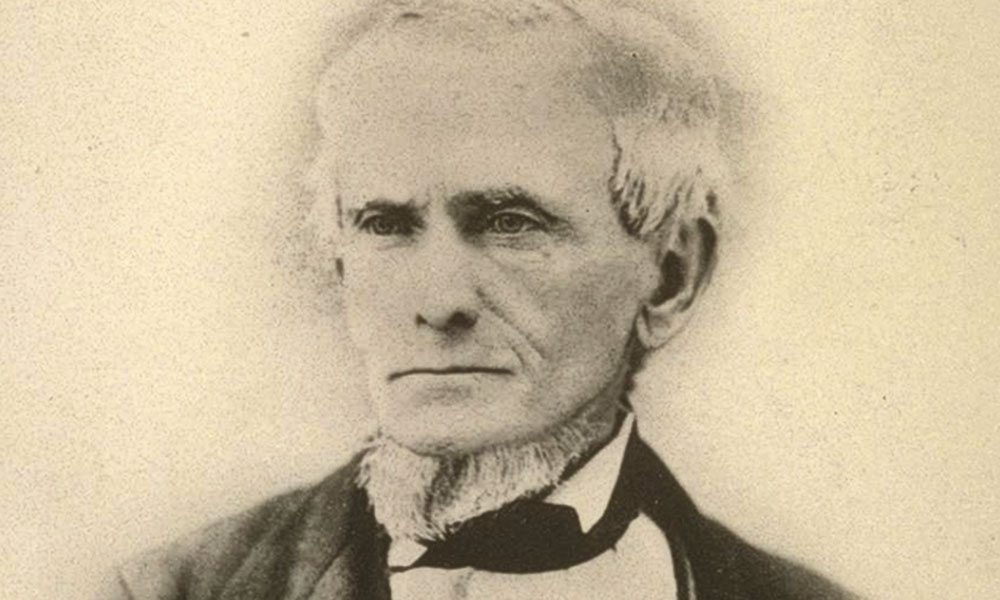

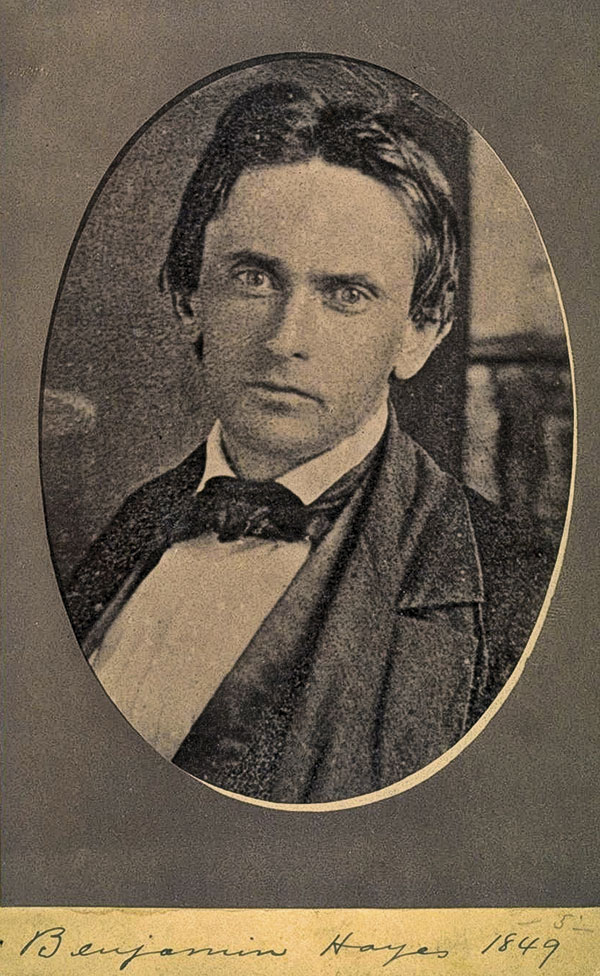

— All photos of Benjamin Hayes courtesy UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library —

Benjamin Hayes was neither an Argonaut nor an adventurer. Born in Baltimore, Maryland, of Irish ancestry, the lean, bookish 35 year old moved to California in 1850 with hopes that the dry climate would improve his wife Emily Martha Chauncey’s bronchitis. She arrived by steamboat in late 1851. By then, Hayes had launched a career as Los Angeles county attorney.

The town’s lawlessness, violence and slave auctions appalled Hayes. “The law,” he argued, “protects all members of the community equally, whether American or not, and punishes the criminal with equal penalties according to the offense, no matter his country, his color, or his race.”

He never wavered in this conviction, even after an attempted assassination in November 1851. The pistol ball fired by an unidentified assailant fortunately only grazed Hayes’s cheek.

His devotion to the Catholic faith and fluency in Spanish gave him special entrée to the Spanish-speaking Californio majority. He saw them as freeholders, not a conquered people. Their innate hospitality, family ties and rural simplicity endeared him.

In 1852, he won a landslide election as the first judge of the Southern District of California— a position he held until his reelection defeat in 1863.

Over those 12 years, the judge rode circuit through the countryside. Armed with a shotgun and bowie knife, he stayed at Californio ranchos, vaquero camps and American Indian rancherias. He recorded natural calamities, ranching histories, the plight of mission Indians and vignettes of the many people he knew or met.

In 1866, the widowed Hayes married Adelaida Serrano, daughter of an established Californio family in Old Town San Diego. That same year, he was elected San Diego County’s district attorney.

He represented Californio families in court when claimants, empowered by the Land Act of 1851, tried to take their property. The law revoked the U.S.’s promise to honor existing Spanish and Mexican land grants ratified at the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

— True West Archives —

His most publicized trial involved slave Bridget “Biddy” Mason, a future Los Angeles entrepreneur and philanthropist. When Robert Mays Smith attempted to take Biddy and another slave Hannah Embers to Texas, a slave state, attorneys filed a writ to free the women. In 1856, Judge Hayes upheld it. He was branded an abolitionist for a verdict he called a “clear constitutional right!”

Shortly afterwards, his son fell from a carriage onto Los Angeles’s main plaza. Three-year-old Chauncey’s rescuer was Hannah Embers. To Hayes’s Catholic mind, this was a sign that the Almighty agreed with his decision.

Hayes sold his collection to Hubert Howe Bancroft in 1874. Inside Hayes’s “heap of old adobe ruins,” what Bancroft discovered staggered him: roughly 60 scrapbooks “stowed in trunks, cupboards, and standing on book-shelves.” Hayes, Bancroft recalled, “gave me his heart with it….”

A judge who believed the law was the touchstone of frontier order and a scholar who amassed an extraordinary body of early California history, Hayes, who died on August 4, 1877, at age 62, was a man who accepted everyone, in a society fractured by racial and ethnic divisions.

Victor A. Walsh is a retired historian from California State Parks. His articles have appeared in American History, California History, Journal of the West and The Christian Science Monitor, among other publications.