— Courtesy Jerry L. Bryant Collection —

The night shall be filled with music, and the cares that infest the day shall fold up their tents… and…silently steal away.

Such is the case when the shimmering twilight settles upon our gulch city, and the band begins to play on the balcony of the Gem; when the hurdy-gurdy girls begin to pound their heels on the dusty floor; when the banker’s daughters begin to hit the pianos in the homes of sin and shame and shriek like distressed banshees the words of popular airs.

—Black Hills Daily Times, May 7, 1880

Only a few days after the Great Fire of September 26, 1879, Al Swearingen was one of around ninety business owners who published a petition for a system of six-inch water mains along Deadwood’s principal streets, along with fire hydrants. They vowed to pay “reasonable rates” for the water.

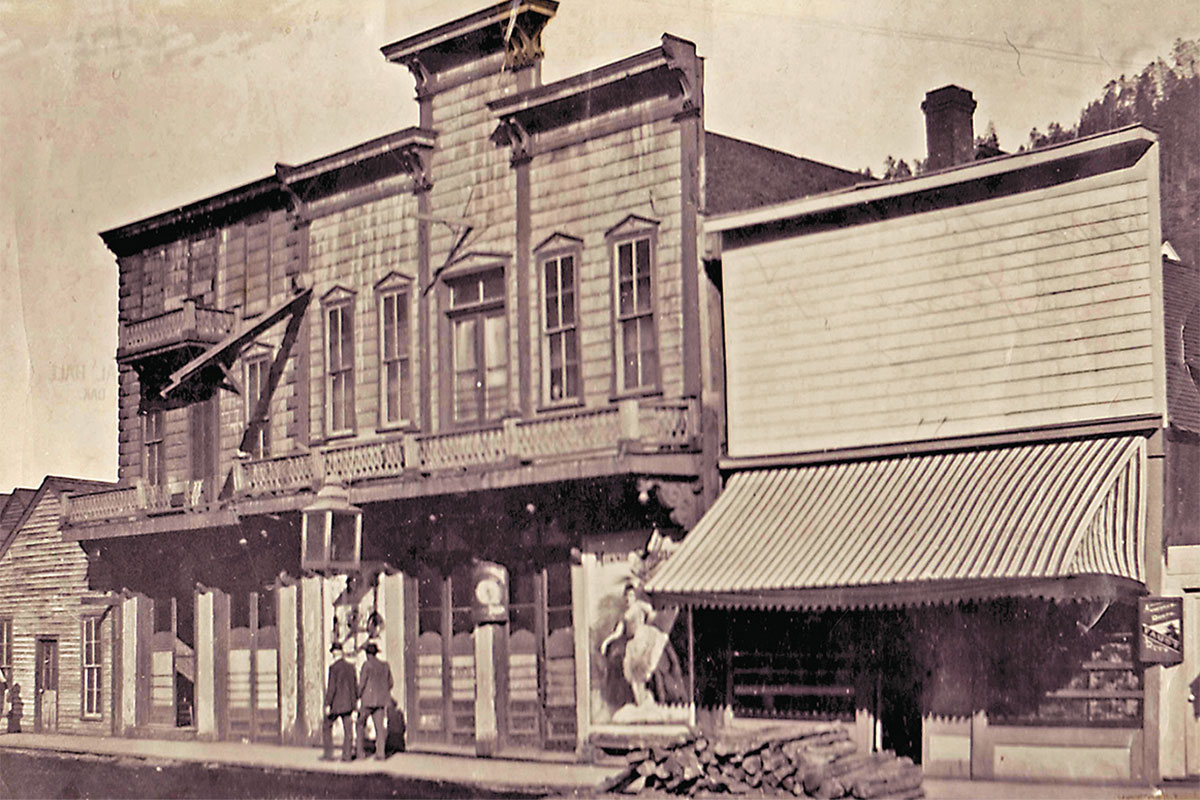

Like most downtown business owners, Swearingen also went immediately to work rebuilding a bigger and better Gem. Surely to his great delight, his neighbor and nemesis, the Bella Union, did not rebuild. By October 5, the Gem Theatre’s replacement foundation was in, and a new building began to rise on it. “Al has faith in the Black Hills and the Gem Theatre,” stated the Black Hills Daily Times.

This second Gem temporarily featured a dance-hall tent measuring thirty by seventy feet, which was open and busy on October 6. With so many freight wagons full of building supplies and new retail goods arriving, bullwhackers and muleskinners helped fill the place. Gambling tables crowded the front of the tent, while the girls and their partners danced in the back.

The dedication was held on November 27, two months after the Great Fire. By the end of December 1879, Swearingen had put true improvements into the rebuilt “New Gem,” as it was temporarily advertised.

The Gem Theatre is Reborn

— Courtesy Jerry L. Bryant Collection —

The theater/saloon portion measured eighty by ninety feet, with thirty-foot ceilings and generous floor space without view-blocking support poles. Nineteen private boxes hung from the truss-style roof on “strong iron rods…thus obviating the necessity of posts throughout the lower floor.” Among the second-floor boxes were a “wine room and a bar.” Also on the second floor was the Gem’s own “water plug,” or fire hydrant, its “keys” (water-line opening and hose-connecting tools) in the fire department’s keeping. The structure’s interior was “finished and furnished in A No. 1 style.”

Standing on Main Street facing the Gem, you would see the first-floor entrance doors sheltered by the second-story band balcony.

Entering the building, you would immediately find yourself in the saloon with a bar, gambling games like faro and poker, and drinkers’ tables and chairs. Moving past the saloon brought you into the theater filled with rows of chairs and the occasional round table. Hanging above each side of the audience seating was a row of private rooms or boxes with doors and curtained windows, where a man could take his whiskey, cigar, and “lady” of his choice for a little privacy during the show or at any other time. Space beyond the stage was occupied completely by the stage sets and scenery.

The Cancan and Red Cloud

In January, Swearingen made a radical change in the format of the Gem’s entertainment when he introduced an act titled “The Pleasures of Paris.” This was the first time that a Deadwood audience could witness a scandalous Parisian dance, which Swearingen advertised as “the original Can Can as produced in Philadelphia at Fox’s American Theater.”

Swearingen advertised that the cancan was a “smash hit” with the miners and bullwhackers of Deadwood.

In only two weeks, Swearingen changed the bill entirely with all new performers, but the cancan was in such demand that it could not stay away. In February, the top of the Gem’s bill was “Hell, or Seven Dizzy Blondes” (“to wake up the young bloods and some of the old heads”), but the cancan still was the crowd pleaser.

For most of 1880 the Gem’s entertainment had been steady and for the most part spectacular, at least by mining camp standards, but in August 1880, Swearingen decided to go above and beyond his norm. In an article titled “Ho! Tenderfoot,” he informed the public that he would bring in a large group of Oglala performers.

Sioux Perform at the Gem

— Courtesy Deadwood History, Inc., Adams Museum Collection, Deadwood, S.D. —

The list of famous Native Americans who would appear at the Gem began with Chief Red Cloud and his wife, Lone Wolf, and read like a roll call for a bona fide Sioux war party. Two of the Oglala who had visited the Gem Theatre earlier in the year, Johnnie-Come-Lately and Woman’s Dress, were there, along with sixteen other warriors.

As the group came into town for the three days of performances, they whooped and hollered, charging up and down Main Street on their war ponies. Twelve-year-old Estelline Bennett and her younger brother Robbie heard the sound from their home and raced along Gold Street to the head of the wooden stairs down steep Lee Street, where they watched the Gem’s band bang and thump its way up Main Street followed by Red Cloud and his band of warriors. “Their brilliant eagle feathers dipped and swayed as they rode. They were armed with bow and arrows and let out blood-curdling screams,” Estelline later wrote.

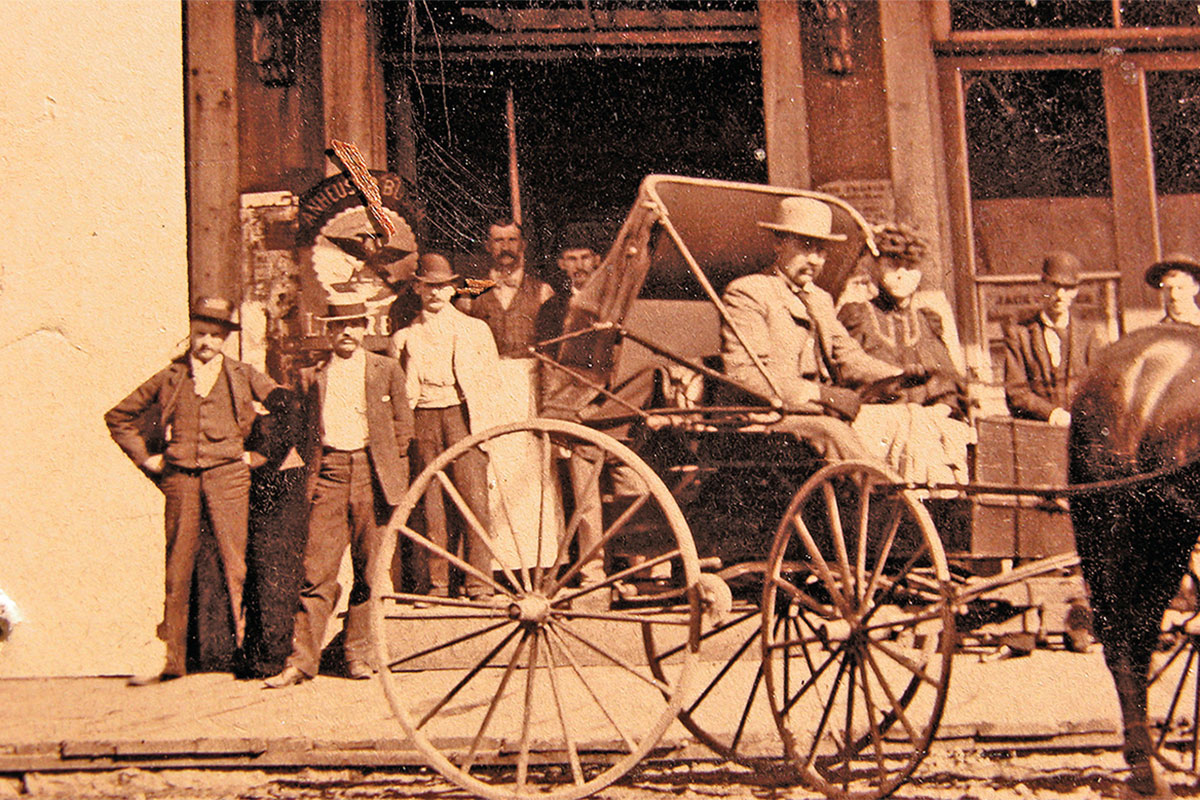

Red Cloud had actually come to Deadwood to address the grand jury in the same trial that had brought Woman’s Dress to Deadwood earlier in the year. On his arrival, his small band set up camp at the Mammoth Corral in Fountain City.

The following day, Red Cloud’s speech to the grand jury was followed by the Times with much interest. The newspaper gave a blow-by-blow description that mentioned that Red Cloud, born about 68 years ago, was becoming deaf enough that he appeared to yell his testimony to the court. But this did not mean that he was in any way disrespectful; on the contrary, he addressed them as though he were speaking “to the Great White Father in Washington.”

When Red Cloud was not performing at the Gem or testifying at the grand jury, he hired a buggy and the African American Civil War veteran Samuel Fields (or General Fields, as he was often called on Main Street and in the newspapers) to show him around the town. Fields had earned no small amount of notice as an eloquent orator, skilled equestrian and natural leader. Indeed, a few years earlier, in Denver, Fields had launched an independent campaign to run for Congress. Escorted by his interpreters, Red Cloud saw the sights and enjoyed his fair share of lemonade and soda water, but the escorts would not allow him to “take fire water.”

As for the good folks of Deadwood, the show that the Indians put on was a hit and considered educational. With the wars between the Lakota and the white trespassers still fresh in the minds of most adults, probably more than a few felt the hair on the back of their necks rise as they watched the event. Band member Joe Gandolfo beat the “tom tom” as Red Cloud and his band, in full regalia, performed several dance ceremonies, including love dances, war dances and scalp dances. The Gem was packed upstairs and down, and the music was described as “not only splendid but loud. It made the whole lower end of the city shake.”

Deadwoodites loved the show and claimed Red Cloud really loved it. In a brief but telling article, the Times informed Red Cloud’s public that he was “so infatuated with show business that he was considering touring the eastern cities and Europe.” Through a translator, he supposedly let it be known that he was looking for a “wide-awake” manager.

The Gem Faces Competition

It is worth noting that in 1882 a new enterprise began on Lee Street—a saloon and music hall on the former site of the Theatre Comique. Proprietors were Tom Miller and former Gem employee Dan Doherty. The latter started various saloons in Deadwood and elsewhere but never stayed around to make a success of them. (He would die in 1886 from complications of two gunshot wounds at the age of 29.) While Swearingen’s good variety acts held their own against the new competition, he seemed by now to have given up on matinees for Deadwood’s honorable matrons.

Besides that competition for the Gem, the amateur Deadwood Dramatic Society began using Kiemer Hall to present legitimate theater plays, so—of course—the Gem’s brass band greeted the opening act by playing loudly from the Gem’s balcony across Main Street. The Gem band was scolded for making the “exquisite” opening production of the popular hit Fanchon and the Cricket hard to hear. Undaunted, the Deadwood Dramatic company of twelve amateurs and some visiting professionals mounted their October production based on a Victor Hugo story about Notre Dame Cathedral’s hunchbacked, deaf bell-ringer and his protective love for the gypsy dancer Esmeralda.

As surely as the Gem’s activities and reputation had ripened during the last few years, Deadwood’s “nice” crowd had stopped attending its matinees. They had elsewhere to look for decent stage performances. Nevertheless, Swearingen kept on booking variety acts, offered gambling and girls, and likely sold just as much liquor as ever.

Deceived into Signing On

— Courtesy Deadwood History, Inc., Adams Museum Collection, Deadwood, S.D. —

Swearingen regularly had “girls” working for him in what could be called, at the very best, indentured servitude.

By 1884, the Gem was well known among the West’s demimonde, from which most of the staff and male clientele hailed. But Swearingen wanted fresh, young girls around the place, and he didn’t care how badly he deceived them into signing on.

He often went in person to interview the applicants (likely on his trips for hiring new variety acts), but sometimes he handled it by advertising in midwestern farm-town newspapers. He misrepresented the Gem as a fine hotel and restaurant, with maid and server jobs available to proper young ladies. Swearingen didn’t always go in person to escort them west; at least once, Calamity Jane donned a dress and did the honors.

When the women arrived in Deadwood, they learned that they owed Swearingen considerable money for their one-way stagecoach tickets and various travel expenses. Swearingen also supplied new clothing, stylish high-heeled boots, and ornaments—things that impoverished girls with older sisters may never have owned before—and money was due for these supplies.

They, and usually their families, had no money for a return trip; the “application process” had made sure Swearingen learned about the family’s financial situation. Even if they stayed only briefly, the young women would be socially ruined and unable to marry back home, so they were stuck. It was the classic pimp’s maneuver.

Worse yet, the new girl’s purity would be briefly preserved while she worked as a “waiter girl” or a dance partner for hire, becoming known to the patrons. But if Swearingen followed the pattern of other 19th-century brothels, her first assignation would be auctioned off to the highest bidder after the men had a chance to look her over. All that money went to the madam or pimp who “managed” her.

Even though the Black Hills Times long had benefited from Swearingen’s constant advertisements, the day came when the newspaper could no longer ignore how this personification of evil did his hiring. In September 1884, it published a major exposé.

End of the Gem

— Courtesy Deadwood History, Inc., Adams Museum Collection, Deadwood, S.D. —

The Gem closed in 1897 and stood empty for two years. On December 19, 1899, its owner of record was one Joseph Swift of Wilmington, Delaware. The firm of Riley & Carr had taken a lease, put a new false front on the Gem, and were furnishing and repartitioning the interior, with yet another grand opening due soon.

Mr. Riley had worked in the building overnight but had left shortly before 5 a.m. Thus the scene was set for the Gem Theatre’s final act, which opened at approximately 5:15 a.m. on a windless night. Nighttime workers and people on the streets said that flames seemed to burst from several interior locations simultaneously. Those who had passed by only ten minutes previously had seen no sign of fire.

In true Deadwood fashion, the alarm was sounded in the wrong fire station, that of the Third Ward, while the Second Ward station was only two doors from the theater. After this confusion was somewhat settled, fire teams were unable to locate their hydrant wrenches or the hose nozzles—the tools for opening the indoor water hookups added in 1879 when the Gem was rebuilt following the Great Fire.

To add more chaos, someone stepped out in the street and began shooting into the air to signal firemen where to come, even though flames were pushing high into the night sky. At that very moment, the Homestake fire company from Lead and the South Deadwood fire company both arrived. Their water nozzles and wrenches also turned out to be missing.

Somehow, despite all this, the firefighters were able to contain the blaze to just the Gem and its adjoining structures, which were allowed to burn themselves out. By evening, the Gem’s sole remains comprised scorched ground and bits of stone foundation. The den of iniquity that had risen from the ashes once was finally destroyed.

Editor’s Note:

“Deadwood’s Al Swearingen” is an excerpt from Deadwood’s Al Swearingen: Manifest Evil in the Gem Theatre by Jerry L. Bryant and Barbara Fifer published by Farcountry Press. Thanks to Farcountry Press’s Zachary Basinger, the Jerry L. Bryant collection, Deadwood History, Inc.’s Adams Museum Collection, and Swearingen relative and family archivist Bob Harrison for images.

The late Jerry L. Bryant was a historian with a passion for solving the riddles of Deadwood’s past and preserving the Black Hills’ historic sites and stories. He was honored by the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences for his work on the HBO series Deadwood. The late Barbara Fifer co-edited the Montana Historical Society’s journal, Montana: The Magazine of Western History, and authored innumerable magazine articles and books, including Deadwood Saints and Sinners.