— Courtesy Allen Polt —

On March 4, 1869, a rather unlikely candidate took his oath of office as the eighteenth president of the United States. The image of Ulysses S. Grant as a cigar chomping, rumpled Union general whose dogged determination helped win the Civil War and gained him two turbulent terms as commander in chief has basis in fact.

But there was much more to Grant than this familiar portrait. He was a complex product of many experiences that helped forge the man who became one of the great leaders of 19th century America.

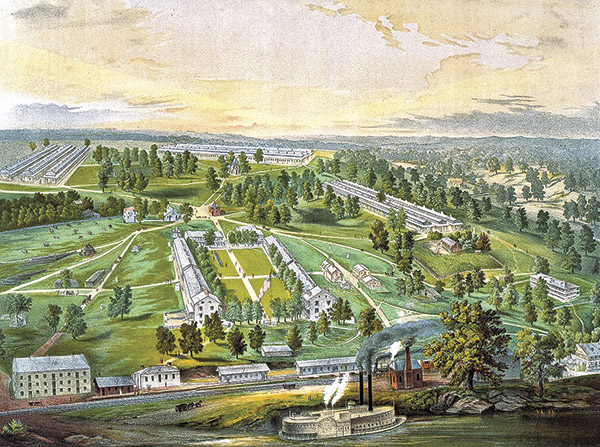

Above all Grant was a true Westerner. His introduction to the region came soon after his graduation from West Point. As a newly commissioned second lieutenant Grant reported to his first posting at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis. After nearly three quiet years with the U.S. Army 4th Infantry, his regiment received orders for Mexico, where he would earn his spurs in battle.

— All images and artwork courtesy of the Library of Congress unless otherwise noted —

Sam, as his fellow cadets knew him, abandoned his birth name Hiram Ulysses Grant (HUG) while on the storied Plain at West Point. He meant to live up to his reputation as the most proficient horseman at the United States Military Academy where it was claimed “rider and horse held together like the fabled centaur….” Now, in Mexico mounted on a barely broken mustang, Grant humbly admitted the recurring struggle to master his stubborn steed “as to which way we should go and sometimes whether we would go at all.”

Eventually the two came to terms. They reached Mexico City where Grant underwent his baptism under fire. Drawing on his gunnery training at the Academy, Grant turned artilleryman by forming a small party of his doughboys (a nickname first adopted during the Mexican-American War for American infantrymen and later popularized in World War I) to drag a mobile mountain howitzer through a series of ditches. He and his cobbled together crew of cannoneers hauled the small, but effective piece into a church’s bell tower. From this height they lobbed 12-pound shot and shell into the enemy. Grant’s innovative actions and those of some of his fellow junior officers drove the Mexicans from their defenses.

— Courtesy of The Chubachus Library of Photographic History —

During this same desperate clash, Grant discovered his future brother in law, Frederick Dent, lying unconscious, with a bullet wound in the thigh. Despite Grant’s rather spare size, he hauled Dent onto a wall where the incapacitated soldier could be seen, reached and taken to medical treatment. Then, the plucky Lt. Grant hurried back to his men to fight again. With Mexico City won, the end of the war was in sight.

In 1848, Grant triumphantly returned to St. Louis, where he married Julia Dent. The couple amused the next several years at eastern duty stations. Despite the boredom of garrison routine they enjoyed themselves.

All this changed in 1852 when the Army shipped Grant off to an unaccompanied tour at far away Fort Vancouver in what became Washington Territory. A lonely, lowly infantry officer, separated from his new family, Grant found life there tedious at best, especially given his various administrative chores.

— Courtesy NPS.gov —

One positive aspect of Grant’s early days in the West was periodic contact with some of the local American Indians. These encounters likely influenced his future views on the treatment of the Western tribes. Early on he observed: “It is really my opinin (sic), that the whole [Indian] race would be harmless and peaceable if they were not put upon by the whites.”

Other experiences did note produce such positive results. For instance, Grant’s investment in several endeavors to supplement his meager Army pay, including a mercantile effort, farming to raise crops and livestock and trying his hand at providing firewood for Columbia River steamboats, all stirred hopes of bringing his family west. He optimistically told Julia in a letter: “that if you and our little boys were here I should not want to leave here for some years to come. My fears now however are that I may be promoted to some company away from here before I am ready to go.”

Those fears proved prophetic. In August 1853, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis informed Grant of his promotion to captain. This news brought a transfer to Fort Humboldt, California. Spending less than a half-year at the remote assignment, Grant missed his family and entrepreneurial prospects in Vancouver. Charges of drinking, which began during his days on the West Coast, marred his reputation and fostered the long, often exaggerated stereotype of Grant the drunkard. Sinking to the depths, Grant took leave, briefly returned to Fort Vancouver to conclude some of his remaining business affairs, and headed back to Julia and his two young sons in St. Louis.

By August 1854, Grant again was in St. Louis, having resigned his commission to try and make his mark in the civilian world. For the next four years, his labors to provide for his little family by running a 60-acre farm and selling cordwood, resulted in nothing but hardship. By 1858 he set out on another money-making scheme, spending nearly a year in real estate transactions. Regrettably he sometimes failed to collect rents, and regularly showed up late for work.

With his finances in ruins, Grant returned to his home in Galena, Illinois, near the Mississippi River, which would play a key role in his future as a Union general. His fortunes remained uncertain, at least until May of 1860 when he accepted an $800-a-year clerkship in his hard-driving father’s leather business. Settling the family in to a modest house, Grant finally made ends meet.

The real turning point, however, came not from eking out a living with his father. Instead Grant’s return to the military brought the success he had long sought. On June 17, 1861, Grant became the commanding colonel of the 21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry regiment. Less than two months later, his West Point training and subsequent martial knowledge brought a commission as a brigadier general of Union volunteers, a promotion that was requested by President Abraham Lincoln.

Grant eventually gained a much-deserved reputation for leadership fighting in the so-called Western Theater, although some military men—both North and South engaged in operations from Texas to California—might have taken offense at this designation. Grant’s fame grew as he delivered results, although these were often costly in both blood and national treasure as well as taking a personal toll as he led the Federal Army to victory.

Undaunted by the strain of command, Grant persevered and was elevated to General of the Army with a four star rank in July 1866. He led the military during a challenging era for the drawn-down, post-war Army with its dual-role of Reconstruction enforcer and Western protectorate of Manifest Destiny. Dealing with problems along the border with Mexico was complicated by the presence of the European-backed puppet Emperor Maximilian I, lawless elements, expansion of the railroads, Reconstruction in Texas and throughout the South, and the major issue of the American Indians (many groups resisting the course of frontier expansion).

All of these challenges of leadership were made even greater when President Andrew Johnson appointed Grant Secretary of War in August 1867. As head of the war department, Grant turned to his one-time Civil War subordinates, William T. Sherman and Philip H. Sheridan, to play major parts in the West. However, he resigned from Johnson’s administration when the U.S. Senate reinstated radical Republican Edwin Stanton as Secretary of War in January 1868. Grant’s short-tenure in Johnson’s cabinet—which swirled with controversy and impeachment proceedings—as well as his standing up to the ill-fated successor to Lincoln—made him a hero and legitimate presidential candidate for the Republican Party in 1868.

In March of 1869 it was against this backdrop that Grant took the oath of office to become president. While his administration weathered considerable scandal, in many respects, as Ron Chernow argues in his new biography, Grant, this former general turned commander in chief should be considered the second most important president of the 19th century after Lincoln. Grant’s presidential tenure (1869-1877) saw the massive growth of railroads in the West, the encouragement of homesteading, which led to phenomenal increases in agricultural production, support of mining operations (including the fateful Black Hills Expedition in quest of precious minerals as one means of pulling the nation out of a devastating depression), and his well-meaning, but controversial “peace policy” to resolve white interactions with the native peoples of the West. All of this demonstrated a desire to bind the nation together and deal fairly with the diverse population in Gilded Age America. In this, Grant genuinely attempted to take up Lincoln’s mantle.

— Courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collection —

Nevertheless, Grant was not a plaster saint nor was he perfect. Indeed, as previously alluded to, both the nation’s Indian policy and the dispatch of George Armstrong Custer to the Black Hills during his presidency had calamitous outcomes. While Custer’s defeat by Sitting Bull and others brought a tragic end to the one-time dashing Union cavalry officer, Grant’s own death proved a sad tale as well.

Cancer sapped Grant’s strength and eventually took his life, but not before he penciled his memoirs to ensure his beloved wife Julia and heirs were not left in financial ruin. In great part he undertook this excruciating labor at the urging of another man of the West, Mark Twain, who agreed to publish Grant’s memoirs. Grant would not live to see the success of his compelling narrative, perhaps the best ever written by a former president. But arguably it all began as a green lieutenant who headed West as a bit player in the march of Manifest Destiny.

John Langellier’s first published article was based on his 1969 senior high school thesis: The Camp Grant Affair: Milestone in American Indian Policy?, which began his decades of interest in the American West.

https://truewestmagazine.com/the-end-of-the-west/