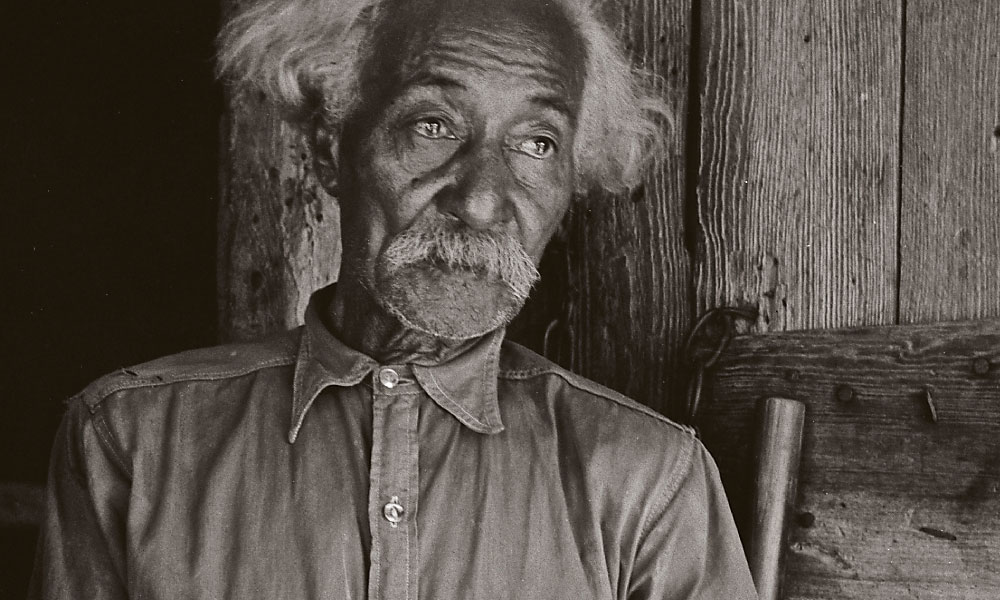

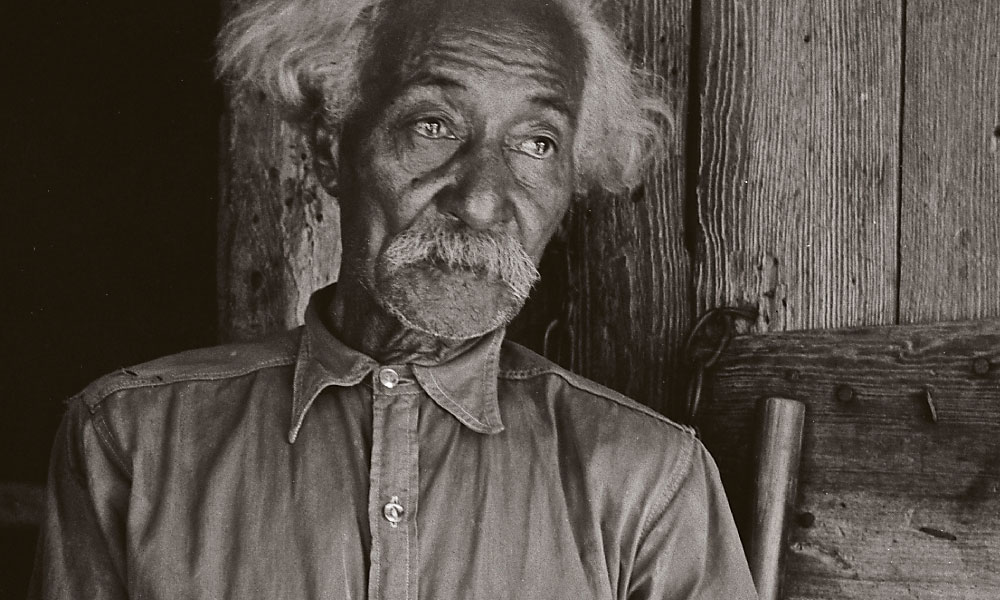

– Dorothea Lange/Courtesy Library of Congress –

He was standing there, as was his horse, Warrior, but both were invisible between the flashes. Shrieking winds cut the rolling grasslands into rivulets of swirling vegetation while crackling lightning snapped like great bullwhips of fire across the horizon. A lone lanky figure stalked the nervous herd from a nearby hilltop.

Rain-soaked, hair smeared with mud and sagebrush, renowned mustanger Bob Lemmons used the herd’s fear of an approaching storm to drive the leaderless mares and colts into a down-range holding pen, with neither horse nor cowboy hurt in the roundup.

In the pre-Civil War days sometime around 1847, Lemmons was born into slavery in Lockport, Caldwell County, Texas. On the eve of the Civil War, the 1860 census recorded the town’s pop-ulation as 2,871 and a separate slave population of 1,610.

His given name is known only to his deceased mother because while still a youth, Bob took a variant of the last name of his employer, Duncan Lammons. At age 17, after being liberated from slaveholder John English at the end of the Civil War, Bob was hired to work Lammons’s ranch property along the Rio Grande at Eagle Pass.

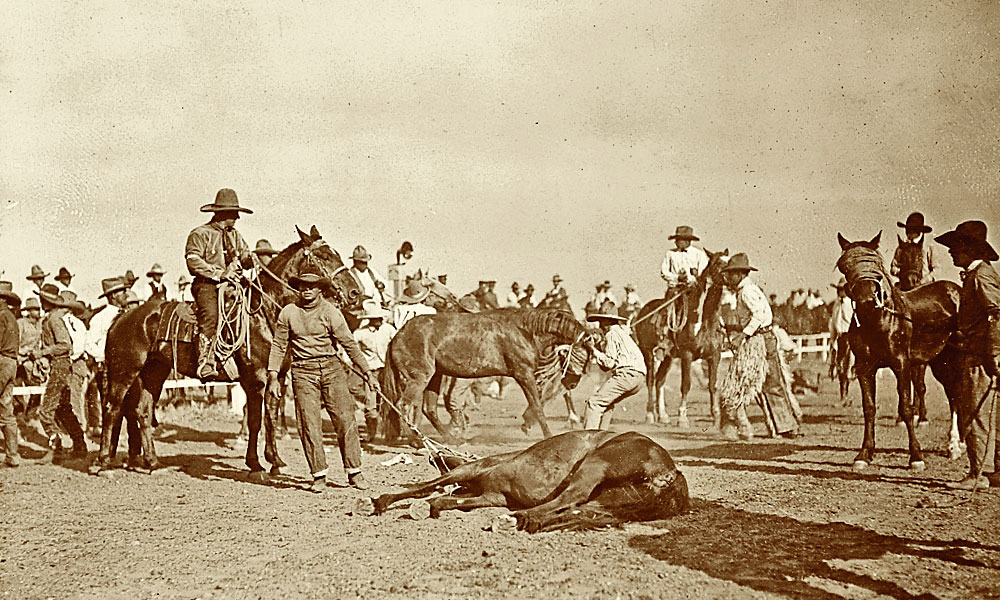

Lemmons mustanged in Dimmit County in southwest Texas, tough country along the Rio Grande nicknamed the Wild Horse Desert. The young cowboy learned the techniques of “brush ranching” and mustanging in the barely inhabited county that was overrun with feral horses. These horses were in high demand as cowboy mounts for roundups during the cattle drives of the 1870s and 1880s.

Lemmons quickly become a legendary mustanger by perfecting a unique method for collecting entire herds of wild mustangs. Working alone, Lemmons would silently infiltrate the mustang herd, ride with them day and night, and then abrogate the herd hierarchy by subduing the lead stallion. Once in control of the herd’s direction, he’d lead the mustangs to a nearby pen.

“I grew up with the mustangs…I acted like I was a mustang…made them think I was one of them,” Lemmons explained. Lemmons’s gritty gathering of wild mustangs provided the means to buy his own 1,200-acre ranch. He learned to read and write and married Barbarita Rosales, with whom he had eight children. He later used his considerable stock of horses and cattle to assist his neighbors financially through the nation’s Great Depression.

“Lemmons showed how skin color was less important in the West, “says Dr. Mike Searles, professor of history at Georgia Regents University, who has extensively interviewed contemporary black cowboys. “Cowboys judge one another by their skills,” he said, and many of the respected ranch hands in Texas were of African and Mexican descendant.

With long white hair, wistful eyes and great gnarled hands that had held the reins of nearly a century of frontier cowboy life and rugged isolation, Bob Lemmons died on December 23, 1947.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Tom Augherton recommends Black Cowboy, Wild Horses by Julius Lester, with illustrations by Jerry Pinkney, to share with young cowhands, and for all ages, J. Frank Dobie’s The Mustangs.