For a brief time in early 1862 Confederate troops occupied what would soon become the Territory of Arizona. This was part of a grand Confederate plan to occupy New Mexico and open a path to California that would make the South an ocean to ocean power.

The so-called “Westernmost Battle of the Civil War” was fought on April 16th 1862 when Union cavalry, traveling east from California clashed with a small force of Confederate soldiers at Picacho Peak on the Gila Trail some 45 miles north of Tucson.

This rugged 3,374-foot peak, a tilted remnant of ancient lava flows, was also a stage station for the storied Butterfield-Overland Stage Line and marked the halfway point between Tucson and the Gila River. The peak has long served as a landmark for Indians, Spanish explorers, mountain men, emigrants and American soldiers traveling along the Gila Trail. Springs located on the slopes of the mountains made it an important stop for thirsty travelers.

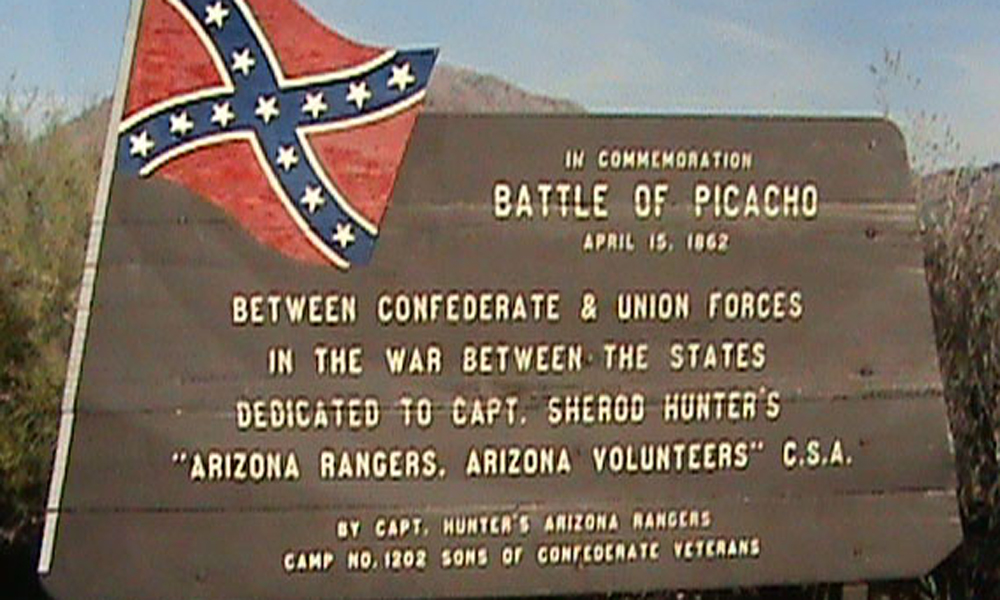

The Confederate occupation of Arizona began a few weeks earlier when Captain Sherod Hunter and his “Arizona Rangers,” numbering some fifty to a hundred men rode into Tucson on February 28th, 1862 and raised the Stars and Bars. Two weeks earlier, on February 14th, the Confederate Territory of Arizona had been officially created.

The Arizona Rangers and Lt. Swilling were originally organized in the Pinos Altos area in today’s western New Mexico as the “Arizona Guard” to fight the raiding Apache but were mustered into the Confederate Army after Colonel John Baylor and his 300-man Texas Brigade advanced into New Mexico in July, 1861,

On March 3rd, 1862, Lt. Jack Swilling led Hunter and his Arizona Rangers north from Tucson to the Pima Indian villages at Sacaton. Swilling had come to the area in 1858 working as a teamster on the wagon road from El Paso to Yuma and was well-familiar with the lay of the land.

Hunter launched a brilliant guerilla-style hit and run campaign capturing and destroying food, supplies and hay that was being stored for Union General James Carleton’s 2,300-man California Column. So effective were his raids the Union spies estimated he had a force of 800 men.

On March 10th Hunter cleverly lured a small Union force led by Captain William McCleave into a trap and captured eleven Yanks at Ami White’s flour mill at Sacaton. Hunter and his men had arrived earlier, taken White prisoner then Hunter posed as the mill owner until he got the drop on the unsuspecting Captain McCleave. The officer furious at being duped offered to fist fight the entire Rebel force to regain his freedom. The Rebs had to admire his spunk but saw no reason to take him up on the challenge.

Twenty days after the capture of McCleave and his men at Sacaton there was a skirmish further down the Gila about twelve miles east of the old Stanwix Stage Station where one union soldier was wounded.

Afterwards, Hunter and his Rangers returned to Tucson. He left Sgt. Henry Holms and nine solders to set up a camp near the old Butterfield Stage Station in Picacho Pass as pickets.

The storied old mountain man, Paulino Weaver, serving as a Union scout, warned the Yanks that Confederates were camped in the pass.

Meanwhile, the Union Army continued to lumber its way up the Gila Trail towards Tucson and on April 16th, 1862, an advance unit led by twenty-six-year-old Irish-born Lt. James Barrett and a dozen men along with their scout John Jones, rode into the pass catching the Rebs by surprise, capturing three, including Sergeant Holmes.

Seven more Rebs were holed up in the thick brush nearby. Jones advised Barrett to dismount and go into the brush on foot and root them out but Barrett ignored the advice and rode in. A volley of furious gunfire greeted them. The Rebels who’d taken a defensive position in the brush opened fire killing Barrett, two enlisted men and wounding three more.

During the Battle at Picacho Peak, fourteen Yanks and ten Rebels were engaged. This battle was not on the scale of Shiloh, Sharpsburg or Gettysburg but to combatants, a firefight is a firefight.

The number of Confederate troops killed or wounded, if any, is unknown. Captain Hunter didn’t mention any casualties when he filed his report and there is no report from a reliable source the Confederates lost any men.

In 1892 the graves of Union Privates George Johnson and Bill Leonard were located and reburied at the Presidio in San Francisco but Lt. Barrett’s grave was never found.

Neither Hunter nor Lt. Jim Tevis, who rode up to Picacho after the fight to get details, reported any killed or wounded. Both were always honest in their reports and didn’t try to hide anything so it’s likely none were wounded or killed. They reported the three men taken prisoner and that’s all.

There was no surviving muster roll and the names of only 67 of Hunter’s Rangers are known. About half were Texans and the rest from New Mexico.

The Union scout John W. Jones was sent into Tucson to gather information. Hunter was suspicious of the spy but after making him swear an allegiance to the Confederacy Jones was released. He was supposed to not go back down the Gila Trail but he headed south towards Mexico then cut across the Camino Del Diablo and returned to Yuma and gave the Union command the size of the Confederates force. California newspapers had been claiming there were thousands of Rebels in Tucson preparing to invade their state.

The California Union force was advancing so slow across the desert old Paulino Weaver got fed up and quit at Sacaton saying, “If you fellers can’t find the road to Tucson from here you can all go to hell.”

Following the incident at Ami White’s mill at Sacaton, Lieutenant Swilling was picked escort Captain McCleave and the rest of the Union POW’s to New Mexico. On the journey he and McCleave spent many an evening around the campfire becoming friends and its likely Jack talked about the possibility of finding gold in the rugged central mountains north of the Gila River that he’d previously explored.

When the group reached New Mexico, Swilling learned that General Sibley’s Confederate Army had been defeated at Glorieta Pass, east of Santa Fe and was in full retreat down the Rio Grande back to Texas. The Confederate dream of capturing the Far West was over. By this time Jack had already decided to desert the Confederate Army.

“I don’t want the blood of white men on my hands,” he told Captain McCleave saying he’d joined the Arizona Guards to fight the Apache, not his fellow-white men. Also, he resented the treatment of the New Mexican citizens by the Confederates who had looted and plundered their way up the Rio Grande. He released McCleave and the others and headed back to Pinos Altos. His days as a Confederate officer were now behind him.