The tall, lanky prospector brushed back his thick, matted, unkempt hair and looked out across a jumble of high mesa hills, scanning the rough terrain on the east side of the San Pedro River. Somewhere out there, he was convinced, lay the vast riches he had long sought.

The region he searched was virtually uninhabitable except for the soldiers who had recently established a military post at the foot of the Huachuca Mountains. There were also a few roving bands of bronco Chiricahua Apache who had stubbornly refused to take up residence on the San Carlos reservation. They were the reason for the lack of population in the fertile mineral-rich valley.

It was a well-known fact this area, some sixty miles southeast of Tucson, was rich in minerals. Several bold men had died trying to wrest the riches from those rugged hills, something that added to the mystic of the San Pedro Valley. The first was Frederic Brunchow, a Russian-German mineralogist who set up operations on the east side of the San Pedro River in 1858. He and several of his men met an untimely death at the hands of his Mexican employees, who robbed and pillaged the place before heading for Sonora. Others, including Arizona’s first U.S. Marshal Milton Duffield would take up residence in the adobe cabin in hopes of getting rich. He was shot-gunned to death in 1874 during a mining dispute by a man said to have been hired to kill him.

It was into this hostile land that Ed Schieffelin ventured in the spring of 1877.

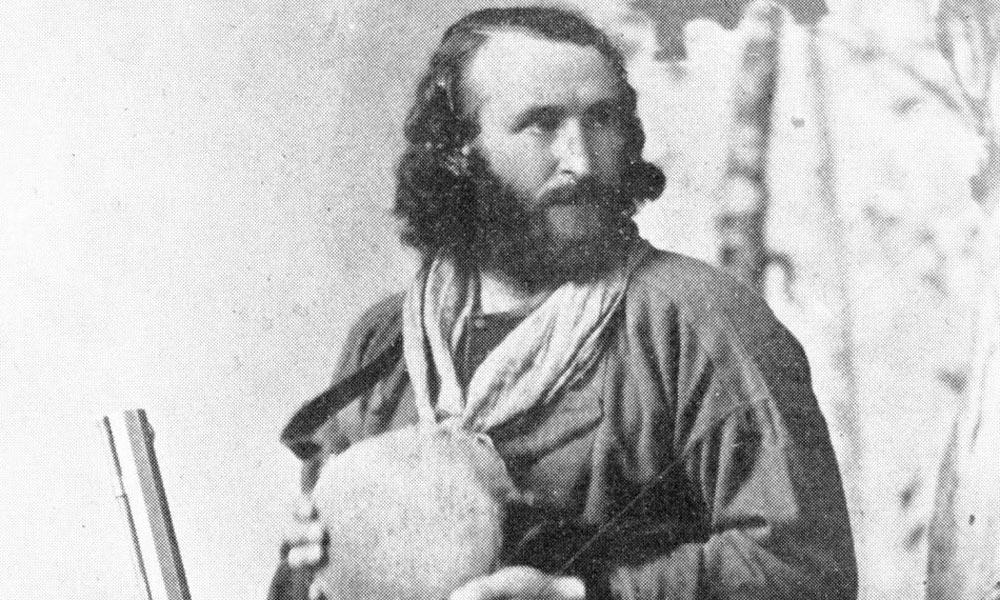

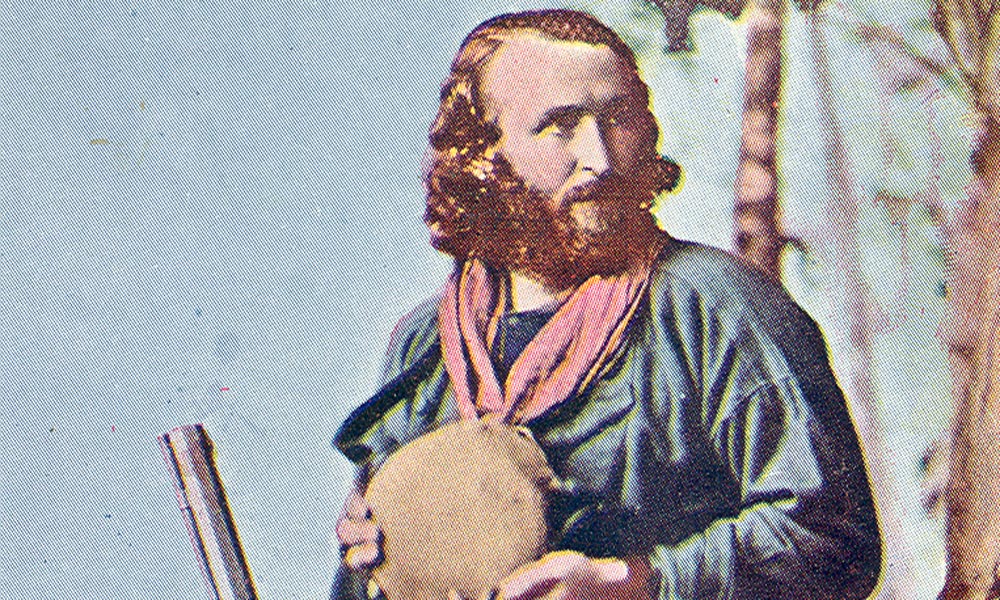

Shieffelin was not yet thirty years old, but looked well past forty. The hard toil and harsh desert sun had taken its toll on the incurable prospector. His long, dark hair hung well past his shoulders and his full beard was a tangle of knots. Tall and lean, the thick-chested and broad shouldered man had taken up prospecting in Oregon with his father before reaching his teens. That was all the education he was to receive. Before he was seventeen Ed was on his own, wading waist-deep in the chilly mountain streams, eking out a meager living off the placer gold he panned.

Before he reached twenty, Ed had been in most of the West’s gold camps. He’d never worked at any other occupation other than to earn a grubstake to continue prospecting. He once wrote that at one time he held a job for a year and a half but quit, saying he was “no better off than I was prospecting and not half so well-satisfied.”

Like most confirmed prospectors who turn their backs on society he’d become more of a recluse, coming out of the wilderness just long enough to earn enough money and then return, alone, in search of the prospector’s elusive dream.

At the age of twenty-four Ed had nothing to show for his years of toil but a few dollars which he promptly spent to outfit himself for a venture into the rugged wilds of Arizona. He arrived in early 1877, prospecting around the Grand Canyon for a spell before heading for the unexplored mountains of southeast Arizona.

He learned that a troop of cavalry was headed to the San Pedro River Valley to campaign against the Apache, Victorio and his warriors so he decided to hitch a ride. When they reached the Huachuca Mountains on the west side of the river he decided to strike out on his own. The soldiers joshed the scruffy prospector who seemed to them a comic, ne’er-do-well saying the only thing he would find in the Apache-infested hills would be his own tombstone.

The story of rags-to-riches prospector Ed Schieffelin and his Lucky Cuss Mine is one of Arizona’s greatest success stories.

Schieffelin was determined to find more than his tombstone. He enlisted his brother Al, an assayer named Richard Gird and the three set headquarters in the old Brunchow cabin overlooking the San Pedro River.

Each day Ed combed the nearby mountains and each time the results were the same, the ore was too low-grade to be profitable. Then one day he brought in some ore specimens from an area a few miles northeast of the cabin. Gird assayed them and with a big grin said, “Ed, you are a lucky cuss.”

He named the mine the Lucky Cuss and it went on to become one of Arizona’s richest silver mines. The Lucky Cuss claim filed on March 15th, 1878, yielded fifteen hundred dollars silver a ton and twelve to fifteen hundred dollars in gold to the ton.

The trio later staked out several other claims in the area and soon a town grew up around the mines. In honor of the soldier’s grim warning, Schieffelin named the town Tombstone.