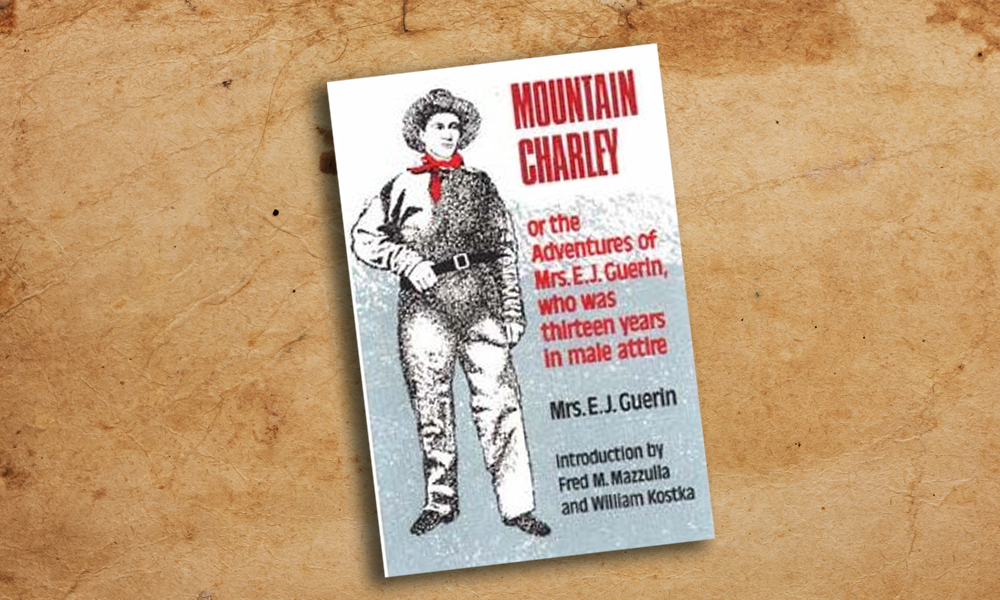

Ever wondered how hard it was to be a woman in the Old West? Just ask Mountain Charley. Or should we say, Elsa Jane, a teenaged widow with two children in the 1840s. “I knew how great are the prejudices to be overcome by any young woman who seeks to earn an honest livelihood by her own exertions,” she’d later say. So she housed her children with the Sisters of Charity and dressed as a man.

Ever wondered how hard it was to be a woman in the Old West? Just ask Mountain Charley. Or should we say, Elsa Jane, a teenaged widow with two children in the 1840s. “I knew how great are the prejudices to be overcome by any young woman who seeks to earn an honest livelihood by her own exertions,” she’d later say. So she housed her children with the Sisters of Charity and dressed as a man.

“I buried my sex in my heart and roughened the surface so that the grave would not be discovered—as men on the plains cache some treasure and build a fire over the spot so that the charred embers may hide the secret,” she noted in a memoir written in 1861.

Over the course of the next 14 years, she was a cabin boy on a steamer, a brakeman on the Illinois Central Railroad, a saloon owner in the California gold fields, a trader for the American Fur Company, and when Colorado had its own gold rush, the owner of a Denver tavern called Mountain Boy’s Saloon.

Not only was she supporting her kids, she was learning how much easier life was as a man: “I began to rather like the freedom of my new character. I could go where I chose, do many things, which while innocent in themselves, were debarred by propriety from association with the female sex. The change from the cumbersome, unhealthy attire of women to the more convenient, healthy habiliments of a man, was in itself almost sufficient to compensate for its unwomanly character.”

Later in life she married H.L. Guerin, who had worked for her as a bartender. They sold the saloon in 1860 and moved to St. Joseph, Missouri, where she wrote her autobiography, notes Gayle Shirley in her “Remarkable Colorado Women”, published in 2002.

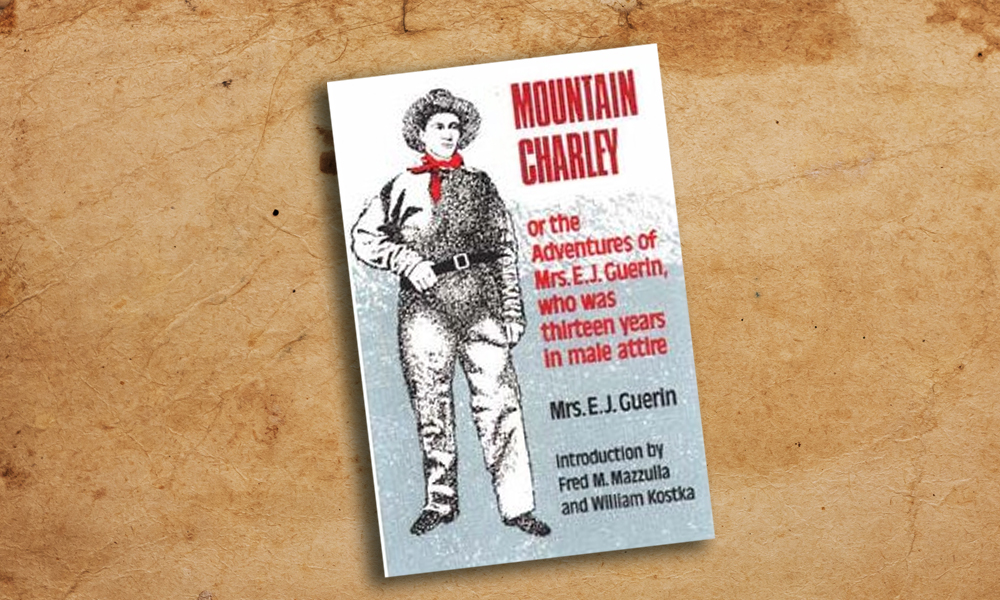

Was Elsa Jane real? Two historians who reprinted her book in 1968 sure think so.

No photograph is know to exist of her/him. And she wouldn’t be the only woman who found men’s garb a ticket to freedom. But her strong words give us added insight into that life.