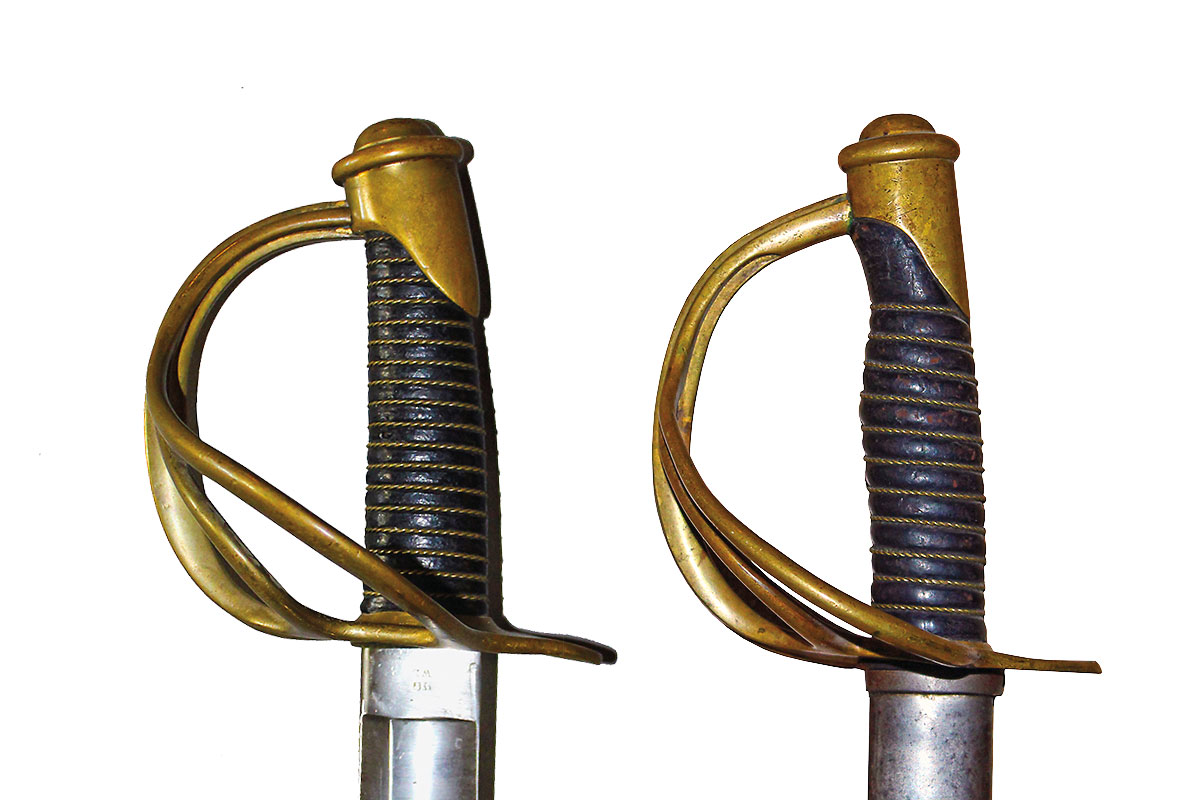

— Courtesy John H. Thillmann Collection —

The U.S. Cavalry’s first official-issue saber—the Model 1833, although graceful and handsome, was disliked by the troops. Considered altogether too light, difficult to thrust properly, and prone to breakage of the blade, U.S. Ordnance wanted a more substantial saber. While considering a replacement, the U.S. Ordnance Department felt that the Ames Sword Co., which produced the ’33 Dragoon saber, was incapable of turning out a suitable substitute, so they turned to England, France and Germany for swords.

An order of about 1,400 various European cavalry sabers was purchased in 1839 as part of a field trial. Deciding on an 1839 Prussian-made blade, an order was placed with the Solingen, Germany, firm of Schnitzler and Kirschbaum (S&K) on August 28, 1840, for 4,155 swords for different branches of the Army. Included were 2,000 of an 1822 French-patterned saber for the cavalry, at the price of $3 per blade. Officially dubbed the “Cavalry sabre-Model of 1840,” they first arrived in the U.S. in October 1841.

— All Photos Courtesy Phil Spangenberger Collection Unless Otherwise Noted —

By 1844, however, Ames had shown that they were now capable of producing a better quality weapon than they previously had, so a contract for another 2,000 Model 1840 sabers was given to that Springfield, Massachusetts, firm. Although quantities were still insufficient for the War Department’s needs for the Mexican War, a second contract for an additional 1,000 sabers was given to S&K in 1847. Nonetheless, Ames eventually supplied 23,700 of the ’40-model saber to the U.S. government between 1845 and 1858.

This was the saber that clanked along the sides of U.S. horse soldiers as they patrolled our Western frontier from 1839 through the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), throughout the 1850s and throughout the Civil War. A welcomed addition to the dragoons’ arsenal was the handsome ’40-model saber. Its only drawback was its excessive weight, earning it the nickname of “Old Wrist-Breaker.” These heavy sabers saw the soldiers through many tight encounters with the Plains Indians when their guns were emptied.

One such encounter in 1850 saw a Sergeant Holbrook and 10 men of the 1st Dragoons, along with famed scout Kit Carson and several Mexican guides, trailing a band of nine Apache cattle thieves. Catching up to them near Santa Fe—a relentless 30-mile pursuit—Holbrook ordered his troopers to charge, killing five of the raiders. Dragoon Capt. William Grier recalled the skirmish as “a very handsome affair,” and reported “two of the Indians were killed with the saber…the contest having become so close.”

Another incident, during the opening months of the Civil War, saw Confederate Col. Earl Van Dorn (later a Confederate general), who admired what he termed “the clank, clash and glitter of steel,” as his Company A, 1st Confederate Cavalry, made up of Texans and former U.S. Regulars, pursued a band of Lipan Apache raiders. Still wearing the blue uniforms of the antebellum Army and armed with Sharps carbines and sabers, they were ambushed by the Indians during a torrential rain. With only a handful of their drenched carbines capable of firing, they quickly drew their sabers and slashed their way to safety, losing only three men, while their sabers had killed 10 of the Lipans and left several others badly wounded.

With the Civil War over and the improvement of repeating firearms, use of the saber was in decline and became largely symbolic, used mostly for ceremonial purposes with isolated actions in the Indian campaigns of the late 1860s. The heavy 1840 model—having been produced during the war by a number of American and European firms including W.R. Horstmann & Sons, P.S. Justice, Gebruder Grah, C.R. Kirschbaum and others—was officially replaced by the Model 1860 “Light Cavalry Saber.” Regardless, the Model 1840 Cavalry Saber had served its dragoon masters faithfully for decades, and has gone down in history as a devastating edged weapon, affectionately called Old Wrist-Breaker.