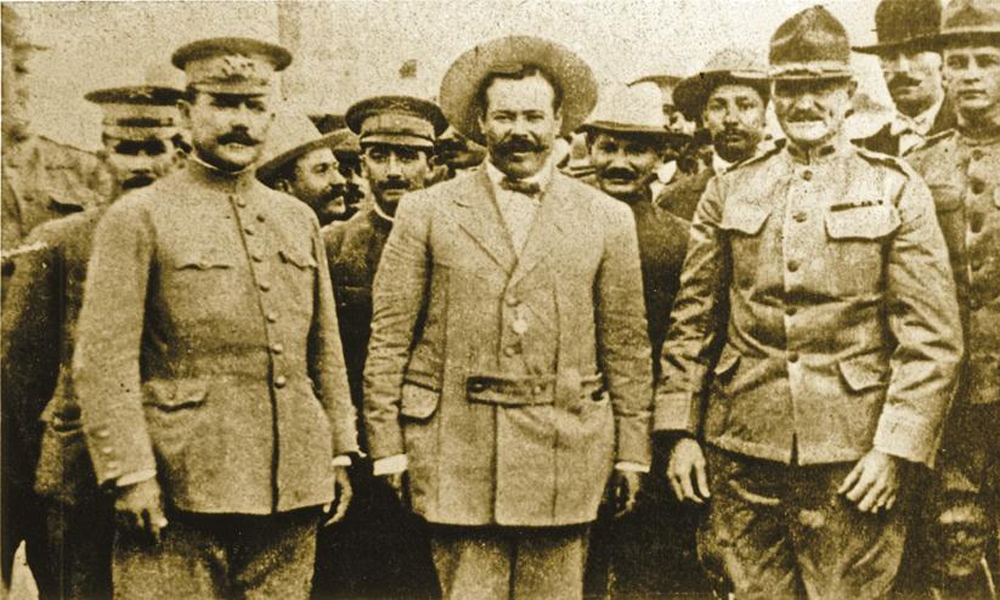

The Mexican Revolution of 1910 gave Pancho Villa the opportunity to get involved in a cause and make his countrymen forget that he was a bandit. He and his band of outlaws joined the rebels in the first year of the fighting. At the age of 22, he was appointed a captain. The dictator of Mexico at the time was Porfirio Diaz, who had ruled with an iron fist since the death of the legendary Benito Juarez, in 1872. Diaz’s slogan was “Bread and the Club.” Bread for the elite; bread for the army; bread for the bureaucrats; bread for the foreigners; and even bread for the Church—and a club for the common folk and those who chose to differ with him, was efficiently wielded by the ruthless Ruales, Diaz’s’ personal police. His rule by force made him the most efficient despot to rule in this part of the world. Haciendas were like feudal estates; and elegant monuments to the rich were everywhere as aristocracy was in full bloom!

Most of the revolutionaries fought to free Mexico from the dictator Diaz and create a democracy. At first, Villa was in the fight only for personal profit. Later, he became a True Believer in the rebel cause.

Pancho Villa idolized the rebel leader, a California-educated visionary named Francisco Madero. Unlike Villa, Madero was an aristocrat and a man of great learning. The two were very different but shared a common bond–they both loved Mexico. In the months that followed, the rebels under Villa’s brilliant leadership, won battles at Casas Grandes and Juarez. Victory for the rebels came when Diaz fled to exile in Europe. Mexico was free! Madero became president.

But the winners had little time to celebrate. The ugly head of despotism reared its head again.

On February 22nd, 1913, President Madero was murdered and a military officer named Victoriano Huerta declared himself president. Huerta’s presidency was punctuated with an orgy of drunkenness, robbery and murder. Villa, now a colonel in the army, hated Huerta and led his bravos to war against him. Villa’s army grew with each victory. He recaptured Juarez and then Chihuahua City. The capture of Juarez was a stroke of military genius. Villa captured a federale troop train, loaded his own troops into the boxcars and wired the federale commander at Juarez, claiming the engine had broken down and requested another locomotive and five more boxcars. The general, believing he was talking to one of his own officers, complied. After the new train arrived, Villa sent another telegram saying the rebels were approaching from the south, cutting the telegraph lines and,” What shall I do?” The commander wired back: “Return at once!” So, Villa’s brigade boldly rode into Juarez on a steam-driven Trojan horse in the middle of the night. By sunrise, Juarez was held by the Villistas.

Given command of the famous Division of the North, the former bandit was now one of the most powerful men in Mexico. Huerta was soon driven from power and in December, 1914, Villa’s army rode into Mexico City in triumph. This was the high point in Villa’s life. He was now a hero throughout Mexico. He was offered the presidency but modestly declined.

During the years 1913 to 1915 Pancho Villa was a real political force. He struck a deal with his friend Emiliano Zapata, the great revolutionary of southern Mexico and the two most famous guerilleros were the toast of Mexico. The difference between the two armies was great. Witnesses said that while Zapata’s humble troops begged for food in Mexico City, Villa’s went on a drunken spree, raping, pillaging.

More trouble loomed, as other political rivals, such as Venustiano Carranza and Alvaro Obregon, conspired against them. Eventually, Zapata would be treacherously murdered by those loyal to Carranza.

General Obregon’s army attacked Villa’s drunken, undisciplined troops and drove them back to Celeya, in the state of Guanajuato, where, in April, 1915, the bloodiest war in the revolution was fought. Villa’s brave Dorados charged again and again against the barbed wire and machine gun emplacements of Obregon to no avail. In the end Villa was soundly defeated and what was left of his once-proud army retreated back to his old haunts in northern Mexico. Villa was once again, just a Mexican bandito.

Bloody battles raged between the armies of Villa and Carranza over the next several months. Many of these were near the American border towns of Del Rio, Texas; and Naco, Douglas and Nogales, Arizona. Curious Americans watched the battles from the roofs of tall buildings or on the tops of railroad boxcars located just north of the border.