In 1906, San Francisco, was one of the jewels of the American West. The California boomtown of the 1850s had grown into the ninth largest city in the United States. Both a port and a railroad town, serving as a major conduit for trade with the Orient, the city was an odd admixture of the Wild West and gentrified city life.

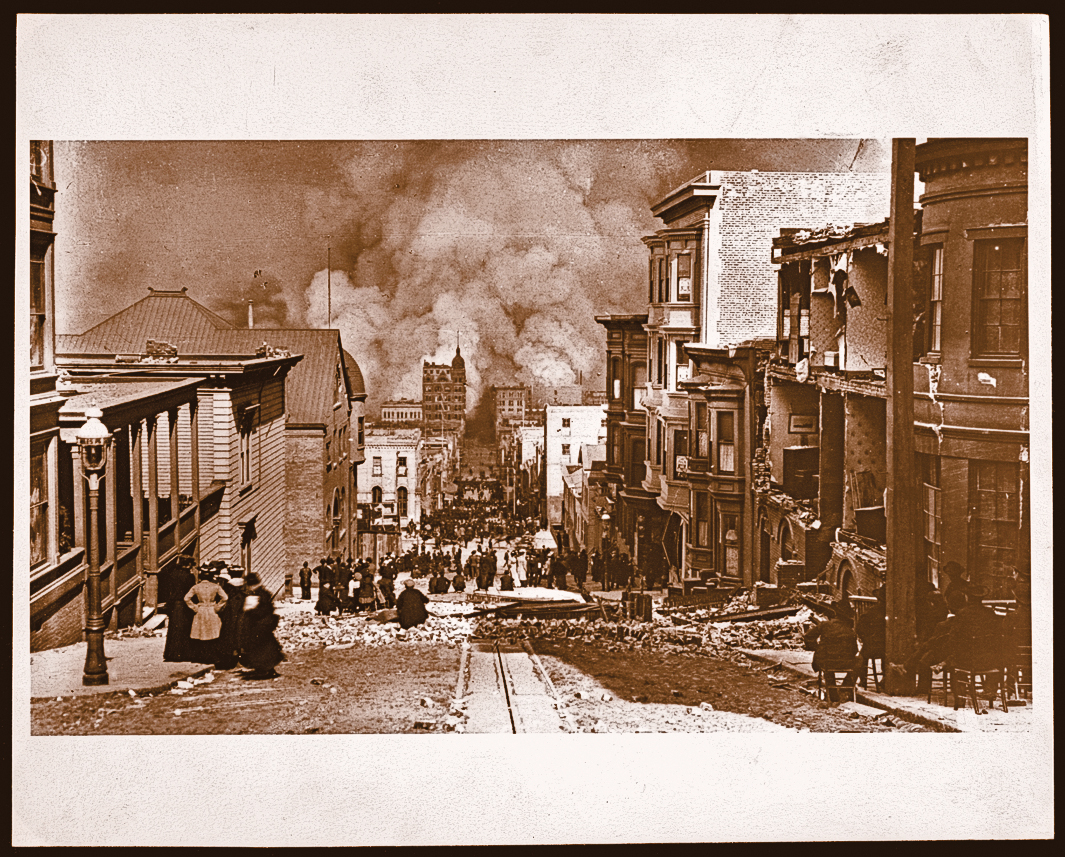

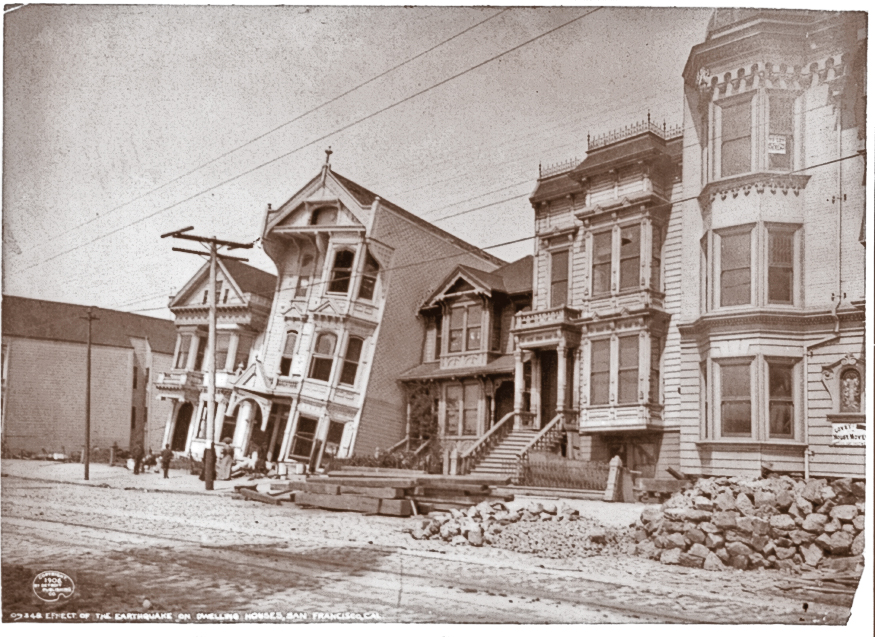

On April 18, in the predawn hours, the city by the bay bristled as bakers busily prepared the day’s treats, men delivered milk, cheeses, butter and ice, and trolley cars carried laborers to work. The illusion that the day was like any other was shattered at 5:12 that morning; an estimated 7.8 magnitude earthquake shook the mighty city for under a minute.

The quake created far more devastation and loss of life than San Francisco’s 6.9 magnitude earthquake of 1989. The 1906 quake set off a series of disasters that eventually killed between 3,000 and 6,000 people, made roughly one quarter of a million people homeless, destroyed approximately 25,000 buildings and leveled almost 80 percent of the city.

“The air was filled with falling stones. People around me were crushed to death on all sides,” earthquake survivor G.A. Raymond wrote. “All around the huge buildings were shaking and waving. Every moment there were reports like 100 cannon going off at one time. Then streams of fire would shoot out, and other reports followed. I asked a man next to me what happened. Before he could answer a thousand bricks fell on him and he was killed…. I thought the end of the world had come.”

Those at home tossed about like a ship at sea as beds bounced around bedrooms, taking the terrified occupants on a wild bucking bronco ride. Electrical lines broke, cracked water lines spewed precious water and miles of natural gas lines ruptured, igniting cataclysmic fires with their flammable vapors.

In town to perform Carmen, the great operatic tenor Enrico Caruso found his hotel ceiling collapsing, raining down a “great shower” of falling plaster. His brave and loyal valet escorted him safely outside the St. Francis Hotel and then went back inside to retrieve Caruso’s luggage. The sounds of the crashing building and people screaming haunted Caruso’s nights for the rest of his days.

Caruso and his valet wound up in Union Square, among other survivors, all fearful that a building would collapse upon them. “…all the city seems to be on fire,” Caruso recalled. “All the day I wander about, and tell my valet we must try to get away, but the soldiers will not let us pass.”

The coalescing of multiple fires into a holocaust obliterated most of the city after the devastating earthquake. The city’s head firefighter, Dennis T. Sullivan, was mortally injured in the quake, leaving his firefighters without a leader to coordinate emergency response. Many first responders, injured by collapsing walls of buildings, could not respond to the stockpiles of explosives at the California Powder Works that required immediate attention.

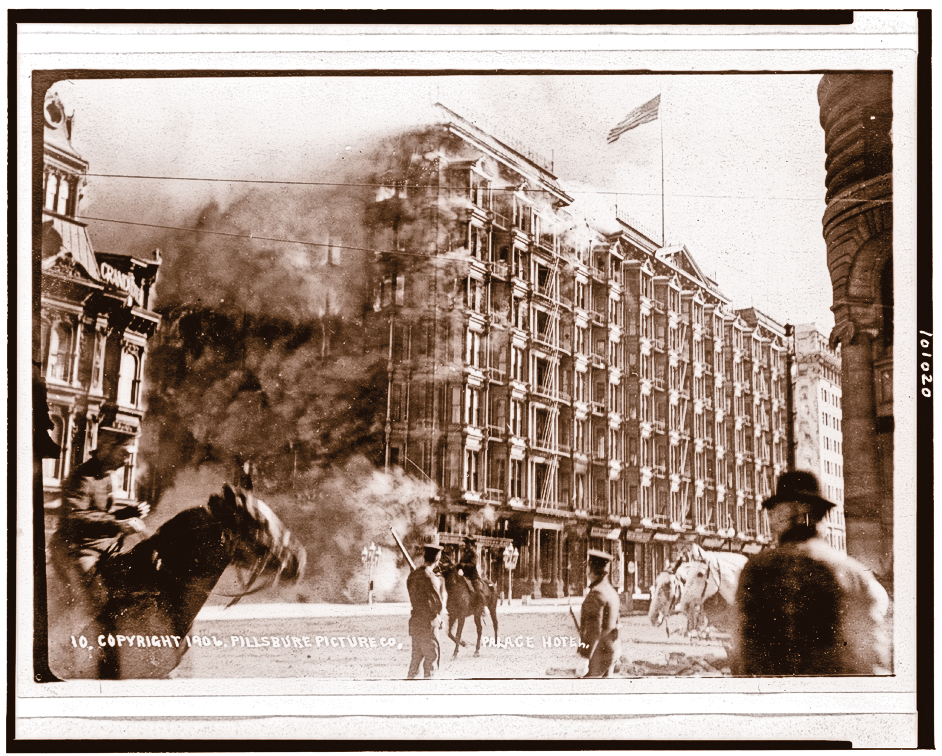

In desperation, the authorities decided to dynamite buildings in the path of the fire. This experiment added to the city’s woes, essentially splintering buildings into kindling and making “them better food for the flames than if the buildings were allowed to stand,” Deputy Fire Commissioner Hugh Bonner recalled.

The choking black smoke turned day into night. Police, unable to rescue screaming people trapped in burning buildings, shot them before the flames could incinerate the hapless victims. A few property owners set fire to their own homes in the correct assumption that insurance companies would pay off on fire damage, but not on earthquake damage.

The inferno burned itself out in roughly four days, leaving a smoldering blackened shell of one of America’s proud cities. After the flames abated, the test of humanity continued. More than half of the city’s 400,000 residents were homeless. These refugees needed food, water, shelter and medical services. Adding to their woes, the destroyed Agnews insane asylum left terrorized mental patients roaming the countryside.

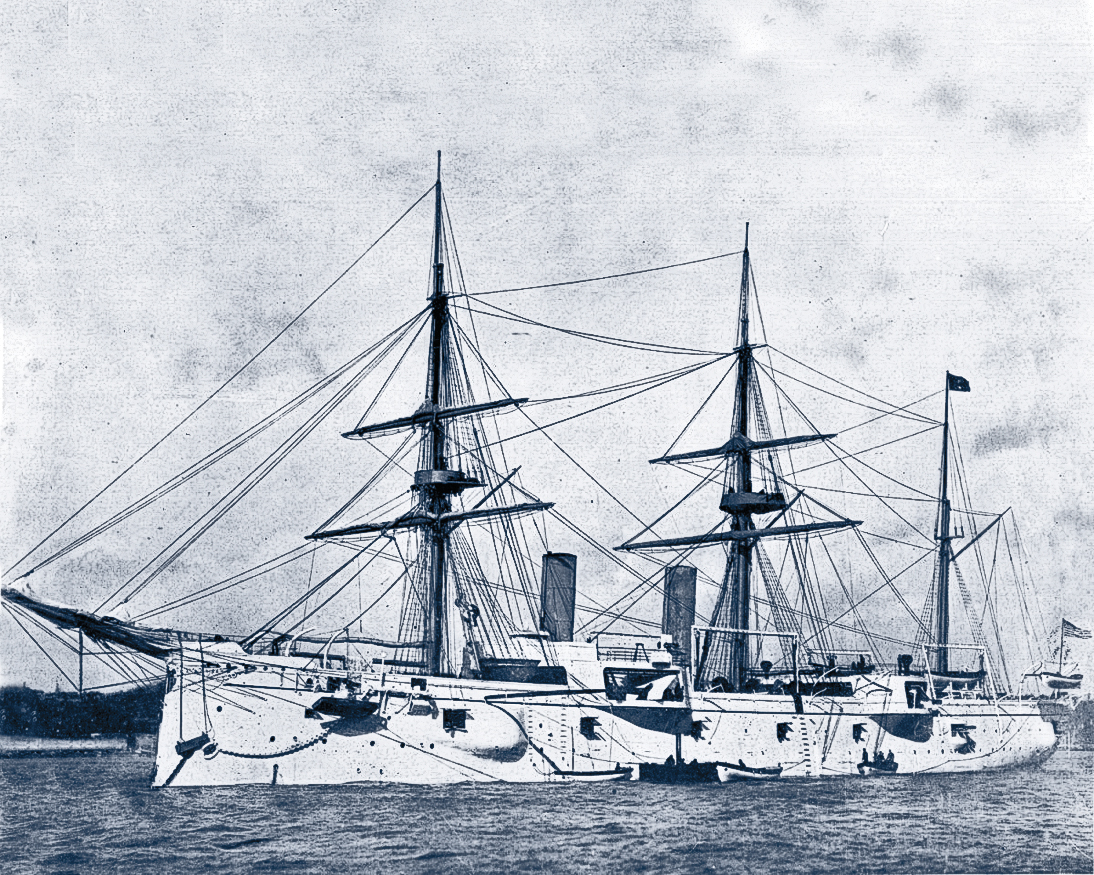

The U.S. military entered the scene. Troops established a telegraph system between the city and Fort Mason. Navy ships, such as the USS Preble and USS Chicago, provided doctors for the refugees. To discourage looting in the area, soldiers were ordered to “shoot-to-kill.” The Army constructed more than 5,500 relief houses, which accommodated a fraction of the refugees. Thousands of tents sprung up.

Relief efforts continued for several years while the city was rebuilt. In current monetary values, losses exceeded six billion dollars. The Golden Gate City rose from the ashes, but many of its residents moved to the relative safety of the Los Angeles area.

The San Andreas Fault had impressed its deadly potential onto the American psyche.

Terry A. Del Bene is a former Bureau of Land Management archaeologist and the author of Donner Party Cookbook and the novel ’Dem Bon’z.