— True West Archives —

In 1864, an irascible 51-year-old Nicholas Earp proclaimed himself a wagonmaster and offered to lead a group of Iowa emigrants to California. Sarah Jane Rousseau kept a diary throughout the seven-month trek, and she has left us glimpses of the father who raised the famous Fighting Earps.

It’s not a pretty picture. Mrs. Rousseau describes Nicholas Earp as a man whose reaction to backtalk was volcanic: “It made him awful mad and he was for killing. He used very profane language and he could hardly be appeased.”

Disagreement was an insult and would set off an hour-long tirade with threats to abandon the emigrants in the wilderness for their opposition. There was discussion of the role “too much liquor” played in his temper.

On November 24, Mrs. Rousseau gave us a direct observation of Nicholas Earp, the father.

“This evening Mr. Earp had another rippet with his son Warren [for] fighting [with] Jimmy Hatten. And then Mr. Earp raged about all the children, using very profane language and swearing that if the children’s parents did not whip them as he did or correct their children, he would whip every last one of them himself. He shows every day what kind of man he really is. He is such an uncouth and foul-mouthed person I think we made a terrible mistake engaging him and furnishing him horses and provisions to lead this wagon train west.”

This is not the strict but ethical paterfamilias played by Gene Hackman in 1994’s Wyatt Earp. Nicholas Earp beat his sons. He cowed and terrified his wife and daughters. He always had some dispute going with their neighbors. He repeatedly packed up his family and moved on, to escape unpaid debts.

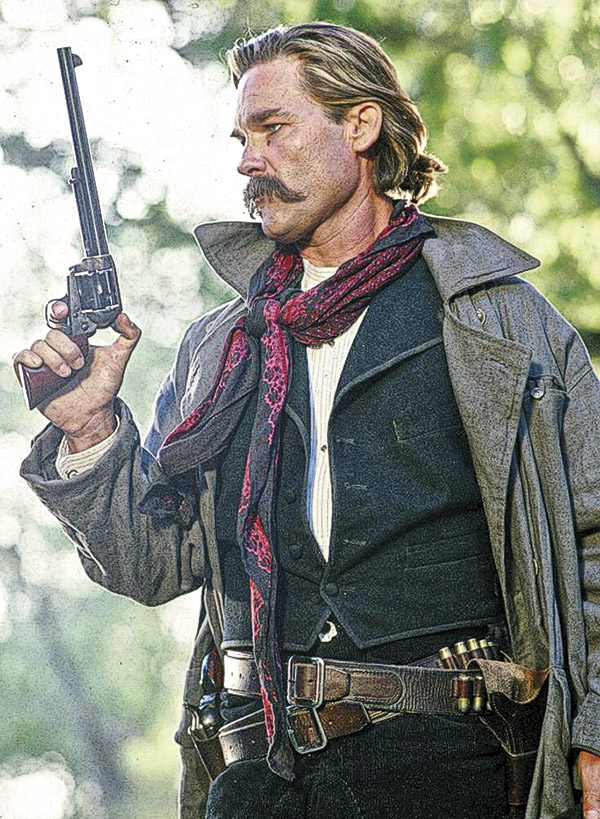

There are two common responses to household violence. Many follow in the abuser’s footsteps, inflicting the same treatment on another generation. Others become protectors of the weak, using their own hard-won strength to stand up to bullies. Unlike Wyatt Earp, 1993’s Tombstone does not directly address the Earp Brothers’ childhood, but in Kurt Russell’s portrayal of Wyatt Earp, I see a moving portrait of someone who is trying to be a better man than his father.

— Courtesy Buena Vista Pictures —

In the opening scene at the Tucson depot, Wyatt sees a stable hand hitting a panicky horse in the face with a coil of rope. Wyatt approaches, snatches the rope away and, in one smooth move, hits the stable hand in the face with it. “Hurts, don’t it,” he says calmly.

Lesson learned and taught: Do not do unto others what you would not have done to you.

Wyatt’s time with Mattie Blaylock was swept under the fictional rug for nearly a century, but Tombstone gives us a good sense of that relationship, and it is in his scenes with Dana Wheeler-Nicholson’s Mattie that Russell’s performance is most touching.

Living with an addict is no picnic, but as Tombstone opens, Wyatt is doing his best. Doc Holliday, knowing what a mismatch Mattie and Wyatt are, needles him a little about the obvious attraction of Dana Delany’s Josephine Marcus.

“Do you consider yourself a married man?” Doc asks him archly.

The answer is yes: “People change, Doc. They grow up.”

An adult man should be good to women: faithful and kind.

That much is in the screenplay, but the most revealing scene is when Wyatt’s brothers Morgan and Virgil are going home to bed with their ladies, but Wyatt has to go to work. As Mattie, Wheeler-Nicholson gives us a breath-stopping moment of inexplicably hostile impatience and annoyance. Russell’s Wyatt tries to mollify her, and she brushes his effort off, and we see his helplessness to make her happy. He doesn’t know what she wants from him, and we can’t imagine how he could please her either.

It takes the two actors only 45 seconds to show us that the relationship is doomed, but the screenplay takes its time and shows us Wyatt’s determination not to yield his self-control. Wyatt meets Josie out riding. He is wary, but her open flirtation is increasingly fascinating. Josie’s breezy enjoyment of life is exhilarating and sexy, but when Wyatt brings that energy home to Mattie, she is too doped on laudanum to respond. He’s left staring at the ceiling, lying next to a broken woman who depends on him.

It’s all there, wordlessly, expressed on Russell’s face. The apple from the tree of knowledge is heavy in Wyatt’s hand. He can’t fix Mattie; Josie wants him to make a move. But the price of happiness is the callous abandonment of a woman who has no one else in the world to take care of her. It is a heartbreaking performance.

Toward the end, the film circles back to the Tucson train depot. The assassination of Morgan breaks Wyatt’s heart. Russell shows us the Wyatt who has spent a lifetime protecting his younger brother Morgan, a boy who has grown up to be a sunny and friendly man because of that protection. Russell does not give us anger. He gives us Wyatt’s howl of guilt: It’s my fault. I brought him here. I didn’t protect him.

In the scene that follows, Wyatt is shattered. Nearly mute with grief, he has no plans except to get out of Tombstone on March 20, 1882, and take his brother’s body home to their parents for burial in California. But when he learns that there are men waiting at the depot, intending to ambush his now-crippled brother Virgil, Wyatt’s grief is transmuted into murderous rage.

And in that moment of volcanic anger and unrestrained violence, Russell shows us the face of Wyatt’s father: a man who was for killing and could not be appeased.

Author of acclaimed novels Doc (Random House, 2011) and Epitaph (Ecco/HarperCollins, 2015), Mary Doria Russell holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology; she taught head and neck anatomy at the Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine.