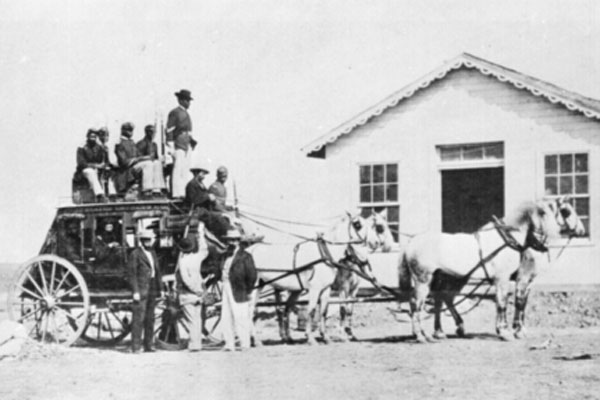

Stagecoach travelers were far more likely to perish from accidents, bad water or what passed for food at the stage stops than an outlaw’s bullets. This was not the case for guards and drivers of the famous Deadwood stage, even the supposedly invincible Monitor armored coach.

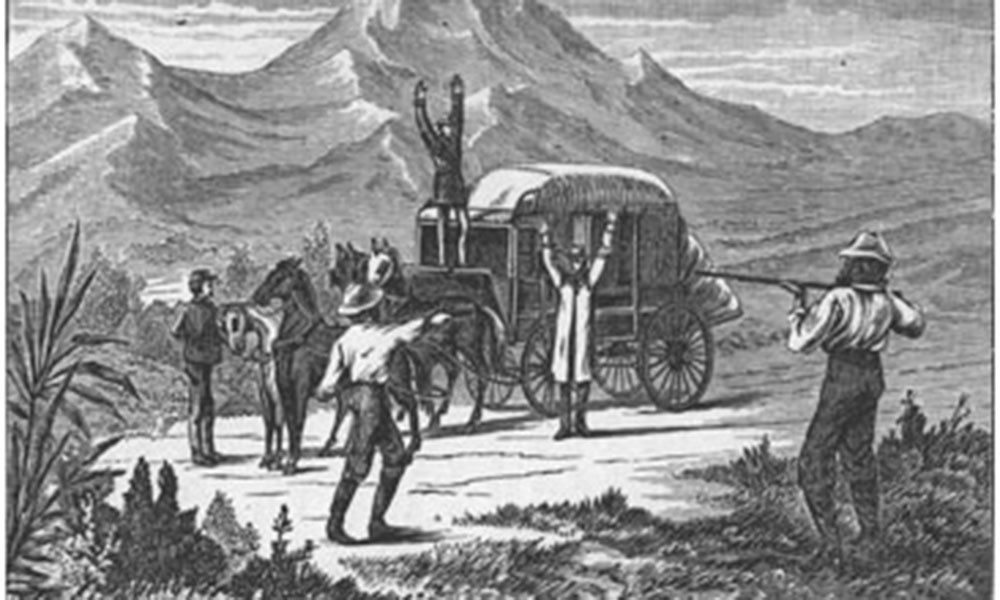

On September 26, 1878, the Monitor rumbled into a well-planned ambush set at the Canyon Springs Station, where stages paused for under 10 minutes as tired horses were swung out and replaced with fresh livestock. Charles Carey and his gang of robbers had taken over the station and were holding the stock attendant, William Miner, prisoner in the grain room of the stable. The robbers cleared loopholes in the stable walls by removing chinking from the logs, preparing a devastating field of fire.

That day, Gene Barnett was driving the Monitor, which also carried guards Gale Hill, Eugene Smith and Scott “Quick Shot” Davis. Passenger Hugh Campbell didn’t realize that his ticket included a dance with the devil.

When the Monitor pulled up to the station, Hill got down to chock the wheels with blocks to keep the stagecoach from rolling. He called out to Miner, but rifle fire was his response. Flying lead whistled all around.

Hill, wounded in one arm, returned fire until he was hit in the chest, the bullet piercing his left lung. Before passing out from blood loss, he managed to wound two or three of the robbers.

Inside the armored coach, Campbell and Smith were wounded. Davis lived up to his nickname and returned a storm of lead in kind. He dragged the wounded Campbell to get cover behind a tree, but Campbell was killed in the process.

Robbers took the driver as prisoner, using him as a shield and making it impossible for Davis to continue his fusillade. Davis abandoned the fight, leaving the robbers to contend with the “breakproof” safe, which they cracked within two hours. The robbers took their loot and tied up the survivors. Miner eventually freed himself and walked to the next station to spread the alarm.

By all rights, Hill should have been dead, but he made it to the hospital in Deadwood and survived. The bullet lodged in Hill’s arm worked itself out in roughly two years, but the lung injuries never fully mended. He took a job as a deputy sheriff and married in 1882. The wounds took many years off his life, but miraculously he had lived to tell the tale.

How to Stop blood loss

When Gale Hill was shot during the robbery, he was left without treatment for hours. That he did not bleed to death from his grievous gunshot wounds was a miracle.

The documents are silent on the matter, but William Miner likely bound Gale’s wounds before leaving for help. Tight bandages would apply pressure to the wounds. If Miner cleaned out debris or any foreign objects from the wounds, he would have accomplished about all he could to reduce Hill’s bleeding.

Hours later, Hill was likely put into a wagon, which pummeled its occupants as it rattled down unimproved roads leading to the next station. Such jarring could have killed an injured passenger by opening the wounds.

Once he got in front of the doctor, Hill may have received a transfusion, a medical practice since the late 17th century. The doctor would have closed up the wounds with sutchering or perhaps cauterizing. He left the bullet or fragments in Hill’s arm. The shot to his chest either passed through Hill or was removed in surgery.

The bulk of the credit for Hill’s survival goes to his iron constitution and will to live, which are both among the most important survival tools.

By Illustrator Andy Thomas

I painted the moment when Gale Hill was frantically returning fire at the robbers ensconced in the stable.

He had been shot in the arm while he was chocking the wheels to keep the Monitor stagecoach from rolling. Hill would be hit by gunfire again…and put out of the fight.

Terry A. Del Bene is a former Bureau of Land Management archaeologist and the author of Donner Party Cookbook and the novel ’Dem Bon’z.