Where did the wagon train party fall short?

Back when I was in high school, a group of us loved to go winter camping out in the middle of nowhere. It was calm and peaceful and beautiful. One of the guys was Karl—and maybe it’s better that I didn’t know his background, for Karl’s direct ancestors were named Donner. Yes, that Donner.

The group that got stuck in the Sierra Nevada in the winter of 1846-47. They ran out of food, so they turned to cannibalism. Of 87 folks in the Donner Party, 41 died. It may be the most infamous wagon train disaster in American pioneer history.

We know of some of the issues that led to the debacle. The party got started a bit late and then was slow on the trail. They took a cutoff that was supposed to save time and mileage—but it had never really been tested and ended up costing the group weeks. They went into the mountains well after experts recommended and got caught in terrible snowstorms that prevented any movement. And it stopped relief efforts for weeks.

Some years after those high school camping trips, I ran into Karl again. He was a human resources consultant, and one of his presentations was “Modern Lessons of the Donner Party.” It was—and is—a fascinating look at the incident through today’s business lens.

Among the issues Karl raised:

1. Lack of strong leadership

Karl’s direct ancestor, George Donner, was one of the oldest members of the train at age 60. He was solid, careful, popular, but not terribly dynamic. And when things began to go wrong, George wasn’t forceful enough to keep people in line.

The other de facto leader was James Reed. He was strong, assertive, outgoing—and disliked by most of the travelers. In October 1846, he killed a teamster on the trail, probably in self-defense, and Reed was banished from the party. (He later led relief efforts).

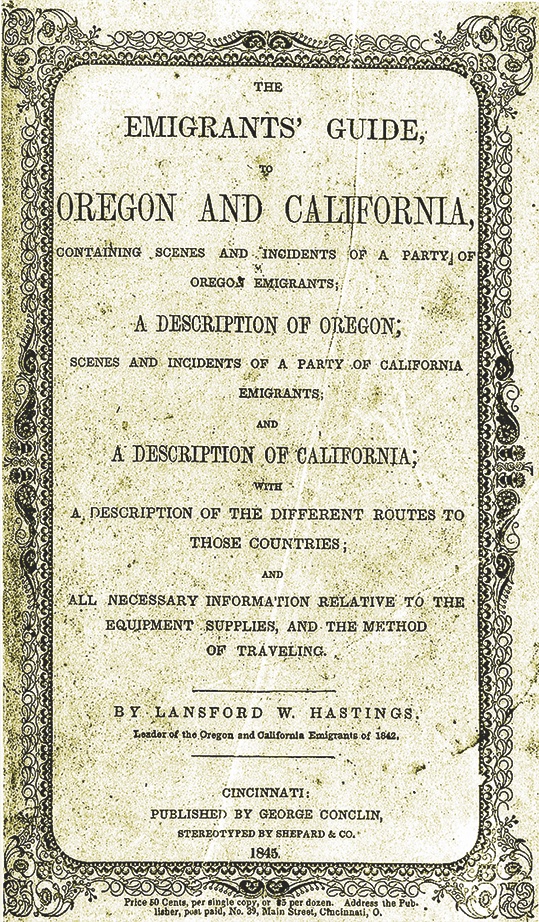

If the strengths of each man had been combined in one person, that might have created the leader the group needed. However, Donner and Reed agreed on one point: to take the Hastings Cutoff, the alleged shortcut to the mountains. They both ignored warnings from several sources that claimed it was untried. That decision, by itself, probably resulted in the terrible situation.

2. Conflict resolution and team-building and poorly handled diversity

Even before the Donner Party hit the mountains, there was division in the ranks. Socio-economic status, ethnicity, etc., drove people apart. A fair amount of it was based on blood: families stuck together, sometimes isolating themselves from others. Things only got worse when the heavy snows hit in the high country. By that time, it was too late to resolve conflicts or build teams. It was every family for itself. A joint effort at survival might have spared lives.

3. Poor interpersonal communication skills

Some folks were too loud and abrasive when it came to expressing their feelings—James Reed being a perfect example. Others just kept quiet, and let issues build up to a breaking point (including dissent about the Hastings Cutoff). They didn’t know how to talk to one another, so frequently they didn’t talk to one another at all. And there was nobody to mediate, to bring the various sides together (another aspect of conflict resolution).

Karl had other points and a few slides, but that hits some of the high points. The bottom line: the group called the Donner Party was unable to work together toward a common goal. Dozens died. Others suffered from frostbite, PTSD and more for the rest of their lives. Worst of all, they were tagged as cannibals, a designation nobody wanted.

In case you wondered, when Karl got hungry on the winter camping expeditions, he went for a candy bar. Whew…