Since 1988, when award-winning author Richard White published his first volume of history, The Roots of Dependency: Subsistence, Environment, and Social Change among the Choctaws, Pawnees, and Navajos, the Stanford University Margaret Byrne Professor of American History has set the bar high for his peers in Western American history.

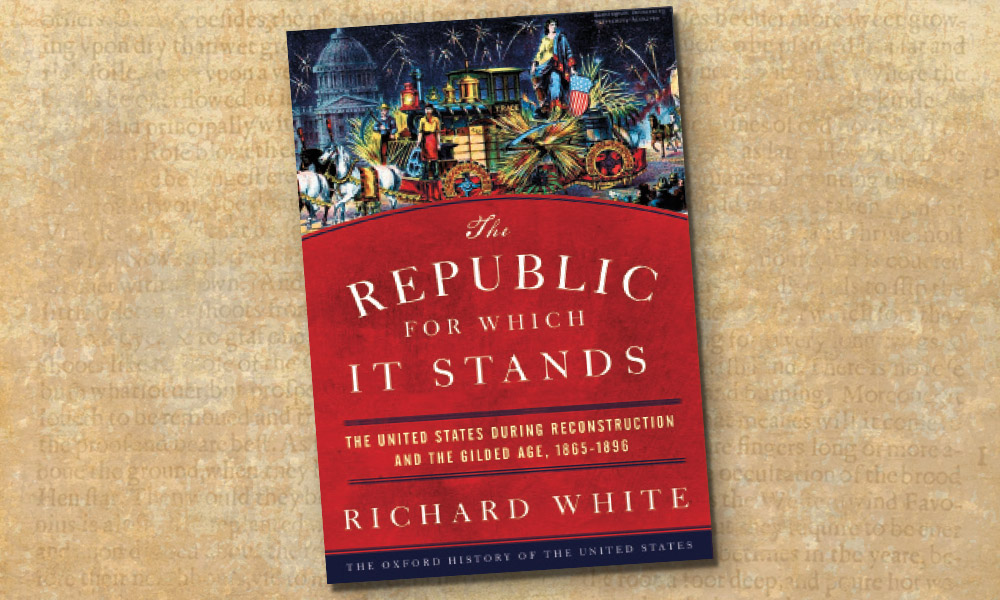

Well-known for his work, including Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America and “It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own”: A New History of the American West, White has produced a magnum opus of 19th-century American history with his latest book, The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896 (Oxford University Press, $35).

White could not have anticipated the timeliness of the release of the 941-page volume, which was published in the last quarter of 2017, in the midst of one of the most divided and rancorous eras in American political, economic, racial and ethnic history.

Readers of his insightful and extremely well-researched and well-documented prose will discover a 30-plus-year span of American history, especially the conquering, settlement and industrialization of the West that is still reverberating in American politics in 2018.

As White writes in his introduction, “The era began with the universal conviction that the Civil War was the watershed in the nation’s history and ended with the proposition that the white settlement of the West defined the national character. Changing the national story from the Civil War to the West amounted to an effort to escape the shadow of the Gilded Age’s vanished twin and evade the failure of Reconstruction.”

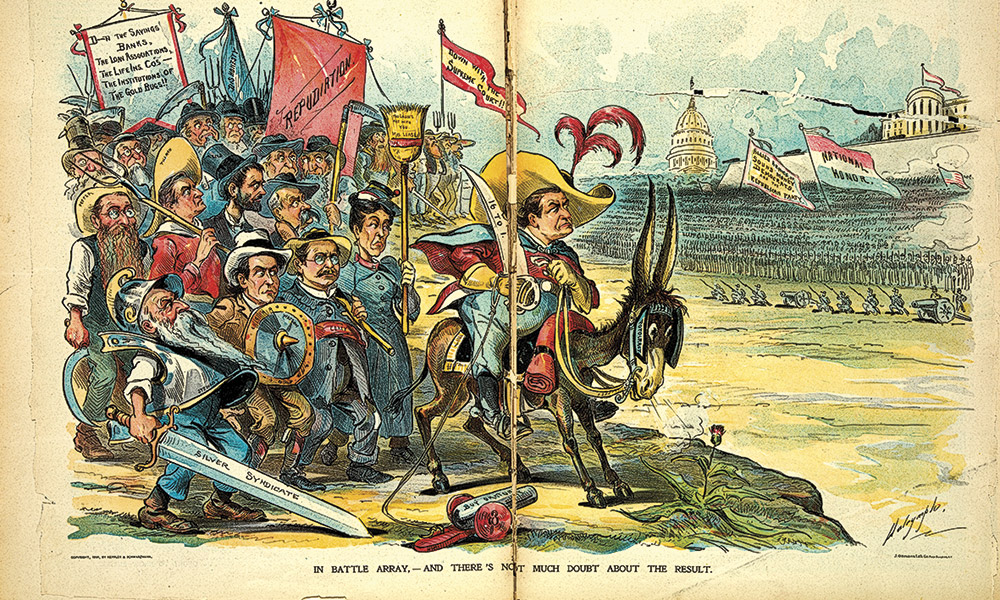

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Readers who are strictly Western history aficionados may at first flush, deem The Republic for Which It Stands too broad for their tastes, or consider it not Western enough, but I would argue that White’s synthesis of American history from 1865 to 1896, interpreted both in the process of history and the place—North, South, East and, most importantly, West—is essential to understanding the West today.

That understanding includes why the use, ownership and future of the current Western United States are inexorably tied to the historic actions of the political parties, federal government and military in the management of the land and peoples during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age. White succinctly summarizes, “In a generation, the United States had taken possession of the western part of the continent, which it had claimed but hardly controlled, and transformed it from Indian country into American states, territories, and a set of constantly shrinking Indian reservations.”

The strength of White’s massive volume is his research, including detailed footnotes (which is rarely seen in mainstream publishing, but I highly appreciate and enjoy versus having to mark the page and try to find the note in over-used and more popular endnotes) and concluding “Bibliographical Essay,” which, for many, will be nearly as important as the text and footnotes.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

White notes that his essay “describes the core scholarship that [he] consulted in writing this book, as well as some of the more influential works on the late nineteenth century.” He also states that it “represents only a fraction of the sources” used and “excludes most of the primary sources consulted. It is designed for the general reader rather than the academic.”

Academic or not, his footnotes reveal his well-thought-out conclusions, and the bibliographical essay is a valuable resource for the writer and historian diving into research of the volatile and violent—and often overlooked and misunderstood—Gilded Age in America.

—Stuart Rosebrook