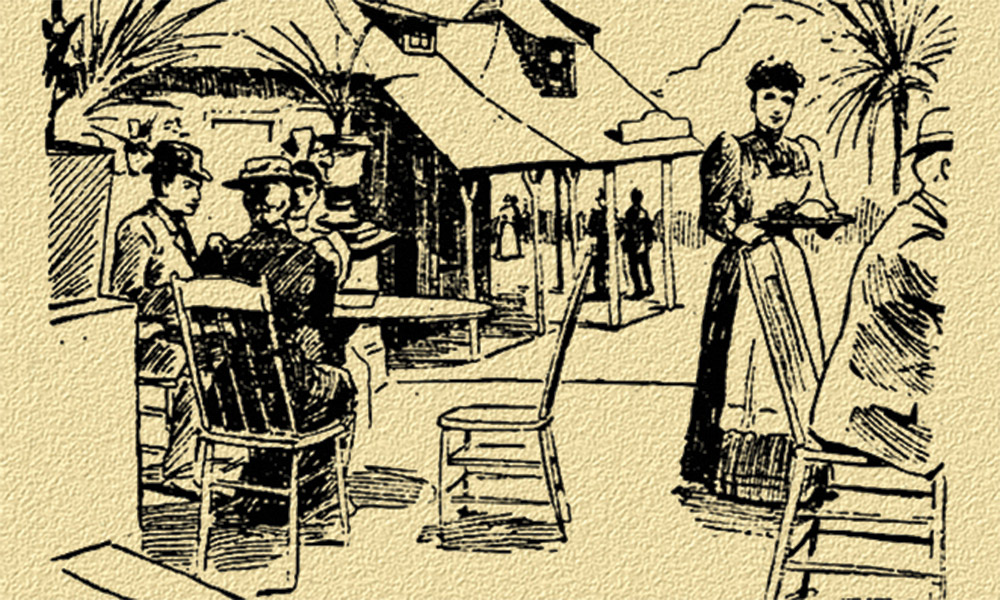

— Published in San Francisco Chronicle, February 28, 1894 —

Fairs gave states and counties the opportunity to show off their best. At both local and international fairs, food helped attendees learn other cultures.

M.H. De Young, the owner of the San Francisco Chronicle, conceived of the California Midwinter International Exposition a.k.a. Midwinter Fair. Construction began in 1893, at Golden Gate Park, where 200 acres were cleared for roughly 100 buildings. The fair opened in January 1894 and ran until July 4.

Paying from 35 cents to 50 cents per meal, fairgoers could eat at various restaurants, including the Scientific Kitchen or the Forty-Niners camp. The latter served “…immortal flapjacks upon which California based its prosperity…. After looking at the food of the ancients, one need be told no more that the Argonauts were hardy people; the flapjacks show it,” the Chronicle reported.

International delights included French food at the Louvre restaurant, German dishes from Heidelberg Castle and buttermilk from Flemish Dairy. Buttermilk may not have been a favorite with the public because the merchant experienced cash flow problems. In April, the sheriff levied tolls on the “visitor who thirsts for a glass of buttermilk.”

Many Midwinter Fair attendees turned a visit into a family outing by bringing lunch baskets. They arrived around 10 a.m. and stayed until the first chill of the air hit. They popped in and out of exhibits, and returned to their picnics to eat dainty sandwiches and drink cold tea.

The Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition opened in Omaha, Nebraska, in June 1898. Among its manufactured goods exhibits was Miss Nellie Dot Ranche’s practical cookery class, which offered demonstrations at least once a week.

After paying 50 cents to enter, folks had the chance to eat at a dozen restaurants, two dozen lunch counters and various tea gardens and ice cream stands. Tea, coffee and pie cost five cents, while sandwiches cost 10 cents. One could also buy a box lunch featuring two sandwiches, two pieces of cake, a pickle, pie and an orange.

Those who hungered for roast beef sandwiches headed to the State of Maine log cabin bean house, where the meat was roasted over red-hot coals. Roast beef sandwiches were so popular that concessionaires had to take out ads to hire meat carvers.

Harriet MacMurphy, an expo “kitchener,” noted strange food products, including a “brownish yellow powder” that piqued her curiosity. She learned it was chile powder, popular in Mexican dishes.

The model kitchen exhibit used the chile powder to make “chila con carni [sic], tamales, tortillas and other strangely named dishes…,” MacMurphy added.

Created by the Gebhardt Chili Powder company in San Antonio, Texas, the chile powder contained peppers, garlic, onion, oregano and other spices.

Try your fair hand at this 1898 Chile con Carne recipe.

Chile Con Carne

2 tbsp. lard or bacon fat

2 lbs. beef, cubed

1 tsp. salt

2 qts. water

1-2 tbsp. chile powder

1 c. tomatoes, chopped, optional

1 onion, diced, optional

1 c. potatoes, diced, optional

Heat the fat in a large stock pot over medium high heat. Add the beef and salt, and cook until brown. Add the water and chile powder. Reduce heat to simmer and cover. Cook for about two hours or until meat is tender. If using, add the tomatoes, onions and/or potatoes when you add the water.

Recipe adapted from Sunday World-Herald in Omaha, Nebraska, October 2, 1898

Sherry Monahan has penned The Cowboy’s Cookbook, Mrs. Earp: Wives & Lovers of the Earp Brothers; California Vines, Wines & Pioneers; Taste of Tombstone and The Wicked West. She has appeared on Fox News, History Channel and AHC.