The young warriors of the Penateka Comanche tribe, several hundreds of them, lined up on one side of their camping ground along the San Saba River in Texas, opposite the women and children on the other. In the center of this array, the three head chiefs, Buffalo Hump, Santa Anna and Old Owl, sat on buffalo robes.

John O. Meusebach rode down both sides of those assembled who watched the six-foot-two redhead, with reddish-blond beard, a newcomer they had nicknamed Sol Colorado (“Red Sun”). Then he and his aides emptied their firearms into the air. Some historians believe this act exhibited foolhardiness; others state the gesture showed confidence in the Penatekas.

Consistently exhibiting nerves of steel in dangerous situations, Meusebach took exception to rumors spread by his adversaries: “The childish idea that I fled or absconded in fear of the excited emigrants, is simply ridiculous,” adding, “I never fled before anything or any danger that I can recollect.”

Germans Colonize Texas

Three years prior to the peace council, Meusebach was not even on this continent. His predecessor had led a German emigration company, the Adelsverein, on a mission to colonize Texas. Organized on April 20, 1842, the company guaranteed each adult male 160 acres of land and every family 320 acres. The largest ethnic group emigrating from Europe, Germans would comprise five percent of Texas’s population by 1850.

Six years earlier, on June 24, the company purchased the colonization contract for land between the Llano and Colorado Rivers, a parcel known as the Fisher-Miller grant. The region was home to the Penatekas who hunted on the Balcones Escarpment and camped in the winter along the San Saba River. Texas stipulated that the Germans had to settle and survey the land by the fall of 1847. This proved difficult, as the government could not assure military assistance, leading surveyors to refuse to enter the region in fear of being attacked by the Penatekas.

The company leader, Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels, resigned in light of these difficulties. Baron O. von Meusebach of Potsdam was appointed his successor. Arriving in the Republic of Texas that summer of 1845, the baron dropped his title of nobility and adopted the first name John. Under his administration as general commissioner of the emigration company, between May 1845—seven months before Texas gained admission into the United States—and July 20, 1847, a total of 5,257 German emigrants settled in Texas. But at first, Meusebach thought German settlement might not happen at all.

Stranded on the Gulf

Hundreds of German emigrants were stranded on the Gulf Coast in Indianola and Lavaca as the emigration company struggled to provide transportation to the promised land. The United States was at war with Mexico.

During the winter of 1845 and spring of 1846, U.S. Army Gen. Zachary Taylor’s soldiers, equipment and provisions were shipped to Lavaca and moved by land from there to Mexico. The U.S. government easily outbid the emigration company’s offers to freight wagon owners. With the company unable to contract for transportation and lacking the funds to buy their own wagons and teams, emigrants could not depart from the unhealthy conditions of their coastal camps. An extraordinarily wet winter at the coast brought sickness to Lavaca and Indianola. Almost 850 people died.

During the spring of 1846, Meusebach again tried to secure provisions and transportation for the stranded emigrants. He was followed everywhere he went—Galveston, Houston, New Braunfels—by creditors of the company and by emigrants. In one of the strangest incidents, a teamster, brandishing a pistol, confronted the administrator, demanding payment for services rendered. Meusebach suggested they settle the issue in a match of target shooting. Meusebach’s first shot hit the bull’s eye. At breakfast the next morning, the teamster extended the credit. Meusebach could talk down one man or a crowd of angry men, like the emigrants he subdued in New Braunfels on New Year’s Eve.

A Fiery Start

Meusebach must have gotten his new year’s wish. In January 1847, twenty men and three wagons set out from Fredericksburg to the Fisher-Miller grant. Meusebach followed them three days later.

Challenges began from the start. The party’s best hunter was severely wounded on the first day and sent back to Fredericksburg. While building a campfire, the emigrants ignited a prairie fire that burned for 36 hours, destroying all forage for the horses for many miles.

In mid-February, Meusebach and his crew came across western bands of Comanches. Rather than war cries, Meusebach received an agreement to meet for a peace council, at the next full moon, at the lower San Saba River.

Meusebach used the interim, seven days, to explore an old Spanish fort. To lighten the load of a pack mule, the crew drank from the wine supply. Sympathy for the poor mule increased until the travelers emptied the last bottle.

On February 18, the men reached the ruins of Presidio de San Saba, established by Spanish authorities in 1750 near present-day Menard. Carved on the portals of the main entrance were names of previous visitors, including that of famed Alamo defender Jim Bowie.

The next day, the crew searched for a lost silver mine the Spaniards had supposedly worked near the fort. To resolve the insufficient funding for colonization, Meusebach hoped to find the silver, but alas, found none.

A Lasting Goodwill

Having just emptied his firearms in a show of goodwill upon his arrival at the Penateka camp, Meusebach was ready for the peace council.

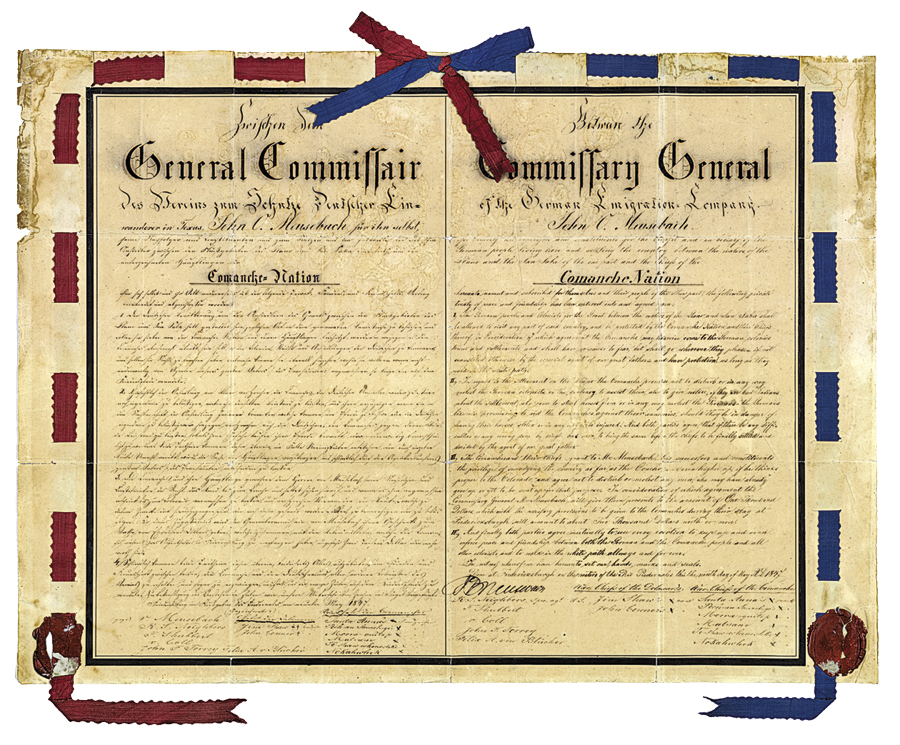

Negotiations took place on March 1-2. Months later, on May 9, the Germans and the Penatekas signed a treaty in Fredericksburg. The Penatekas collected $3,000 worth of presents.

The treaty allowed both Meusebach’s settlers and the Penatekas unfettered access to the territory. It also promised mutual reports of wrongdoing and provided for a survey of land in the area with a payment of at least $1,000 to the Penatekas. The treaty opened more than three million acres of land to settlement.

Despite minor infringements, including Comanche raids into Mexico that violated the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, overall, the Penatekas and the German settlers upheld the peace treaty. Years later, in 1858, former Texas Ranger Jack Hays told Meusebach how astonished he was that the Penatekas were honoring the treaty. Hays said that he “was never molested nor lost any animals during his travel within the limits of the colony, but as soon as he passed the line he had losses.”

The Penatekas even helped German settlers when a cholera epidemic in Fredericksburg took the lives of three of every five settlers. Santa Anna and his men rode into town with bear meat and herbs to nourish settlers who were trying to regain their health. Santa Anna, unfortunately, contracted the illness and died. By late December 1849, he was one of the roughly 300 Penatekas killed in the epidemic.

In August 1859, the U.S. Army moved the band north of the Red River to Indian Territory. By 1875, the entire Comanche tribe had been reduced to 1,597 members. Some Penatekas may have been among the survivors. At Fredericksburg’s annual Founders Day, Comanches occasionally join in, demonstrating that some of them have not forgotten their German allies.

Perhaps one of the reasons the peace treaty was upheld in 1847 was because of Meusebach’s attitude toward the Penatekas. During negotiations, he said to them, “My brother speaks of a barrier between the red men and the palefaces. I do not disdain my red brethren because their skin is darker, and I do not think more of the white people because their complexion is lighter.”

Tim Dasso is a freelance writer in central Texas, where he observes Texas historical sites and researches historical events. He is writing a historical fiction based on events that occurred in Texas’s early years.