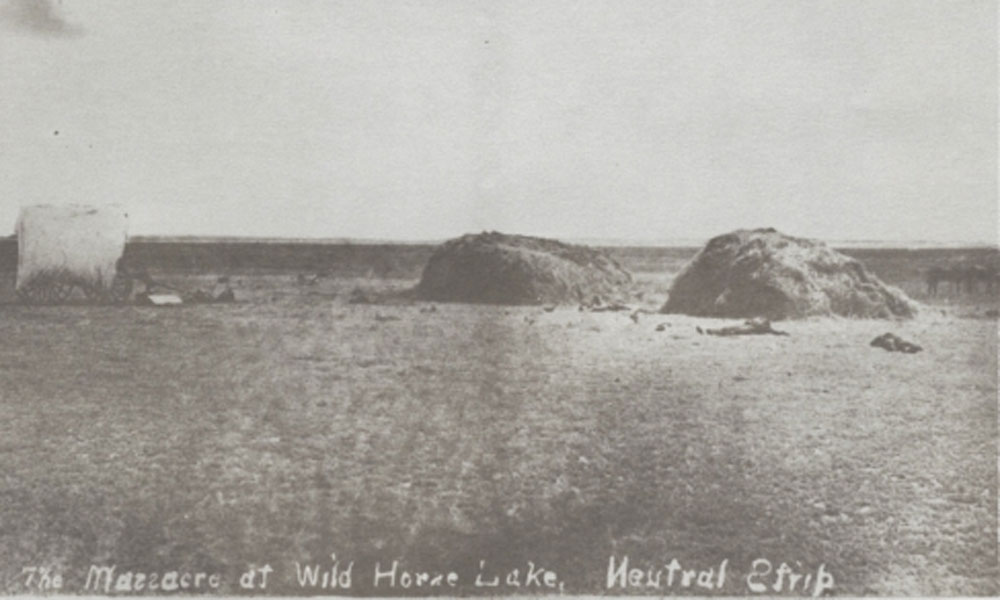

— All Wounded Knee album images courtesy Cowan’s Auctions, June 9, 2017 —

A profit-making enterprise that ended up documenting history may make one’s stomach queasy—especially when a complete picture of how that happened is explored. An album of Wounded Knee photographs was both shocking in its hammer price ($22,000 at Cowan’s Auctions, on June 9, $15,000 higher than its pre-sale estimate) and in the mere fact that such photographs exist at all.

Born in Germany in 1861, George Trager moved to Chadron, Nebraska, in the fall of 1889. He first photographed Pine Ridge Agency in March 1890, capturing a scene of the beef issue. On December 30, when he heard word of the fighting, Trager obtained permission to photograph the site from Gen. Nelson Miles, who was passing through Chadron on his way to Pine Ridge. Arriving there with soldiers and civilians sent to bury the dead, Trager became one of five photographers who captured the events surrounding Wounded Knee.

Trager stood out above the others; he took the only photographs that preserved the bloody bodies strewn on the wintry ground, which historians might appreciate for documenting the abject horror of the massacre, while they detest the fact that the photographer often posed those dead bodies.

To add insult to grave injury, Trager mass marketed these gory photographs. Newspapers publicized the sale, reporting, “…there are a number of beauties among them, and are just the thing to send to your friends back east.”

Not all in the press saw these as beauties. Carl Smith, correspondent for Nebraska’s Omaha World-Herald, commented on the awfulness he saw: “Children just of an age to play tag in a city, and young men and old gray-haired women and warriors” had been killed. He also included Trager in his reporting, capturing the moment when a “wandering photographer propped the old man up, and as he lay there defenseless his portrait was taken.”

To the extent that we know Trager only saw money in these dead American Indians is evident in that he sometimes defaced their humanity by printing his copyright label on the faces or bodies of the dead Lakotas, and he capitalized on each image by printing on the reverse side advertisements for other views he had taken that could be purchased.

That Trager would rearrange the dead, like when he flipped the body of Medicine Man, who had died face down, to present a more gruesome position for the corpse, gives power to why Indians believed photographs stole souls. Trager’s images implied the power of being authentic documents yet hid the photographer’s manipulations.

Even worse, these photographs remind us of the press’s role in inciting this tragedy. On November 29, 1890, Agent James McLaughlin had warned Commissioner T.J. Morgan of this danger: “I deplore the widespread reports appearing in the newspapers, which are greatly and criminally exaggerated…. For they have caused an unnecessary alarm among settlers in the vicinity, who have fled from their homes panic-stricken to places of supposed safety on false rumors that the Indians had broken out….”

Exactly a month later, the 7th Cavalry opened fire on the Lakota camp at Pine Ridge in South Dakota, killing at least 150 men, women and children. Only after it was too late did Morgan report newspapers had helped cause the war: “The sudden appearance of military upon their reservation gave rise to the wildest rumors among the Indians of danger and disaster…corroborated by exaggerated accounts in the newspapers” that “frightened many Indians away from their agencies into the badlands and largely intensified whatever spirit of opposition to the Government existed.”

Newspapers certainly deserved the blame historians have given them for their role in this tragedy. Circulation drives made the last two decades of the 19th century a frenzy for journalists. Newspaper circulation had increased almost six-fold between 1870 and 1900, and the nation’s total population jumped from 11 million to 20 million between 1880 and 1900, reported George R. Kolbenschlag, in his book Newspaper Correspondents and the Sioux Indian Disturbances of 1890-1891.

Yet the journalists themselves exhibited the yin and yang of how the nation viewed Indians. Some were profit-hungry and desensitized to the plight of the Lakotas, like Trager. Others criticized press cohorts, as Gilbert Bailey told Inter-Ocean readers: “There are now at Pine Ridge a host of newspaper correspondents each eager for a scoop, and for lack of reports of bloody combats they explore the teepees of the enemy, stand him up against his wagon, and photograph him with the usual injunctions to ‘look this way, please,’ and ‘smile now.’”

Nobody smiles today when they hear the words “Wounded Knee.”