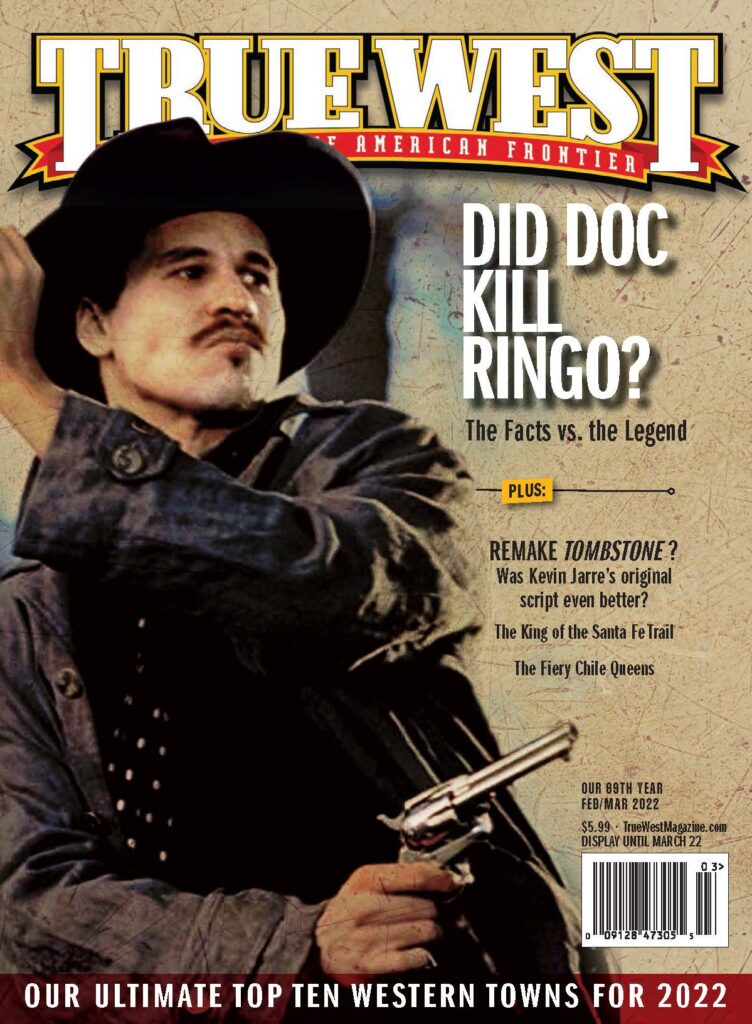

Historians, actors and film critics weigh in on Kevin Jarre’s original script—and whether it should be remade and finally get its DUE.

Everyone seems to agree that Kevin Jarre’s original script for Tombstone was brilliant. So why hasn’t someone dusted off the source material and re-filmed it the way Kevin wrote it? Is it because it’s too long for a movie, as some suggest, or is there a deeper truth about the whole shebang? We asked the participants in the 1993 film to weigh in, along with some of the best historians in the Earp field. Read on, this is very

insightful stuff.

—Bob Boze Bell

Not Ready for Prime Time

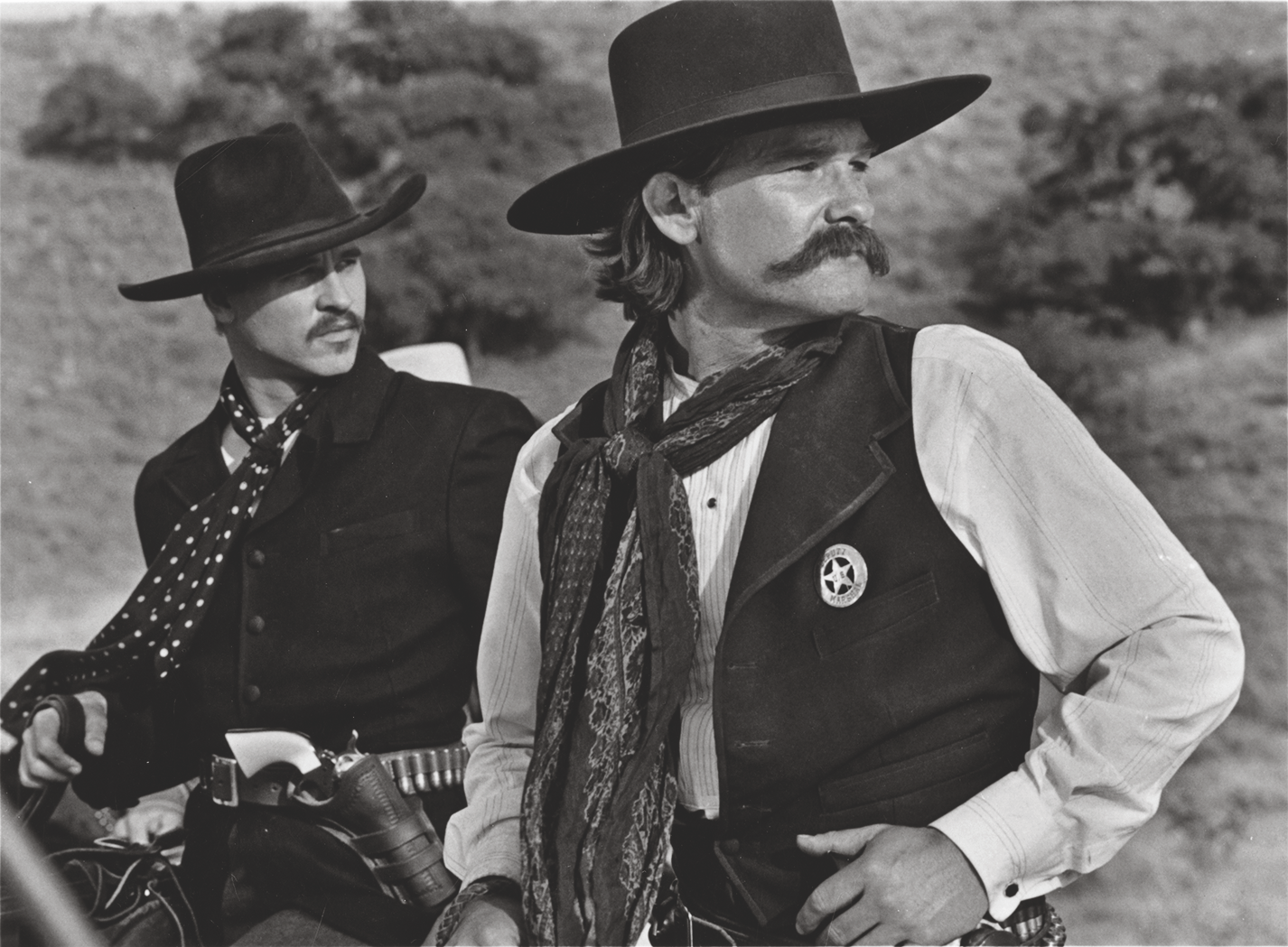

In December 1993, Buena Vista Pictures and Cinergi Productions released the classic modern Western, Tombstone, the story of Wyatt Earp and the shootout at the O.K. Corral. Written by Kevin Jarre, who, in 1989, also wrote the screenplay for the award-winning film Glory, the script was the main reason many actors wanted to be a part of this project. This was to have been Jarre’s first attempt at directing. And, with crackling dialogue, biting accuracy, and brilliant dramatization, the screenplay came closest to telling the legend of the shootout better than any other previous attempt. Rather than an action-packed shoot-’em-up, Jarre’s script focused on a character study of Wyatt, his brothers and Doc Holliday. Sadly, however, as brilliant a writer as Jarre was, his enthusiasm couldn’t offset his lack of directorial experience. He just didn’t have any, and he refused to listen to those who did. Imagine ignoring Kurt Russell, Sam Elliott, Val Kilmer and Bill Fraker when they tried to make suggestions. Many have said it was a shame that Kevin hadn’t had a few smaller productions under his belt before taking on a project of this magnitude. And a review of Jarre’s unused footage clearly supports that contention.

Most of Kevin’s scenes were master shots, visually beautiful but challenging to edit. His goal was to shoot Tombstone on “sticks,” in the style of John Ford, but he either didn’t understand the concept or didn’t know how to execute the vision. The result, wasted time, energy, money and hours of discarded footage. The only scenes Jarre shot that appear in the final release are those with Charlton Heston, and they couldn’t reshoot them after Jarre was released as Heston had already departed the set and wasn’t available.

Within mere days of start-of-production, it was apparent Kevin wasn’t able to bring his script to fruition. While it is not explicitly known precisely what prompted the studio to replace him, it was clear that the fledgling novice would not deliver what the studio expected. Some have said the studio only wanted Jarre’s script, and it was their intention all along to replace him as director; others pointed to Kevin’s micromanage-ment and lack of adherence to a schedule. Still others spoke of scene composition and coverage. Dialogue that previously leapt off the page now sounded stilted and artificial, and the actors’ performances appeared forced and pedestrian.

There were numerous rumors on the set; Jarre was drunk, or doing drugs or was out riding his horse all day, or deliberately being sabotaged. In any case, the studio had had enough, and after considering John Milius and John McTiernan, among others, Jarre was fired and replaced by action director George Cosmatos. For Kevin, a project that began with such high expectations and excitement ended in failure. Several of Jarre’s ideas were used but eventually re-filmed by Cosmatos. In the revised screenplay, parts were pared, dialogue changed, scenes blended. Some said they wouldn’t have agreed to do the film if that had been the original script.

Jarre never again achieved the brief success he had with Glory. He was a script doctor, involved with The Devil’s Own before the script was torn apart in 1997, worked on The Mummy (1999), and supposedly was an uncredited writer on John Lee Hancock’s The Alamo (2004). If he just had a bit more experience, it would have been interesting to see what he could have accomplished with his Tombstone script. However, at that time in his career, he just wasn’t prepared to take on such a massive opportunity.

—John Farkis (Author of The Making of Tombstone: Behind the Scenes of the Classic Modern Western)

A Savaged Script

Simply put, the script Kevin originally wrote was most brutally savaged in the vendetta ride scenes. In Kevin’s script, the action scenes are anchored in an explicit context. That makes those scenes dramatically meaningful and informs the audience as to who exactly is being killed by the Earp party. In the film, as released, the vendetta ride becomes a somewhat confusing montage of scenes that lacks dramatic cohesion. And, one new scene, which makes no sense whatsoever, is added for no discernable purpose. That is the scene of Wyatt’s posse lynching someone in front of the Dragoon Saloon in Tombstone.

If Kevin’s script had been followed, the finished film would have been bigger because more members of the Cowboy gang would have been clearly identified and delineated. And, if Kevin’s script had been shot, the film, as a whole, would have made more sense. Action scenes, without proper previous character development, become meaningless.

Also, if Kevin’s script had been followed, the scenes with Hugh O’Brian would not have been cut. Having O’Brian in the film would have made explicit how Tombstone fits into the larger sweep of previous Earp films and TV shows. In fact, originally, Kevin wanted Burt Lancaster to play Marshal Fred White. If that had panned out, Tombstone would have been a sort of culmination of Earp films. For instance, Harry Carey Jr. portrays Fred White. In the history of Earp films, Harry Carey Sr. played the Doc Holliday character in Law and Order (1932), the very first Earp movie. Then, 25 years later, in 1957, Olive Carey, Harry Carey Jr’s. mother, and the widow of Harry Carey Sr., portrayed the mother of Billy Clanton in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. Both Harry Sr. and his wife, Olive, actually knew the real Wyatt Earp. So there was a lot going on with the casting of Tombstone that was completely missed by film critics.

—Jeff Morey (Historical consultant for Tombstone)

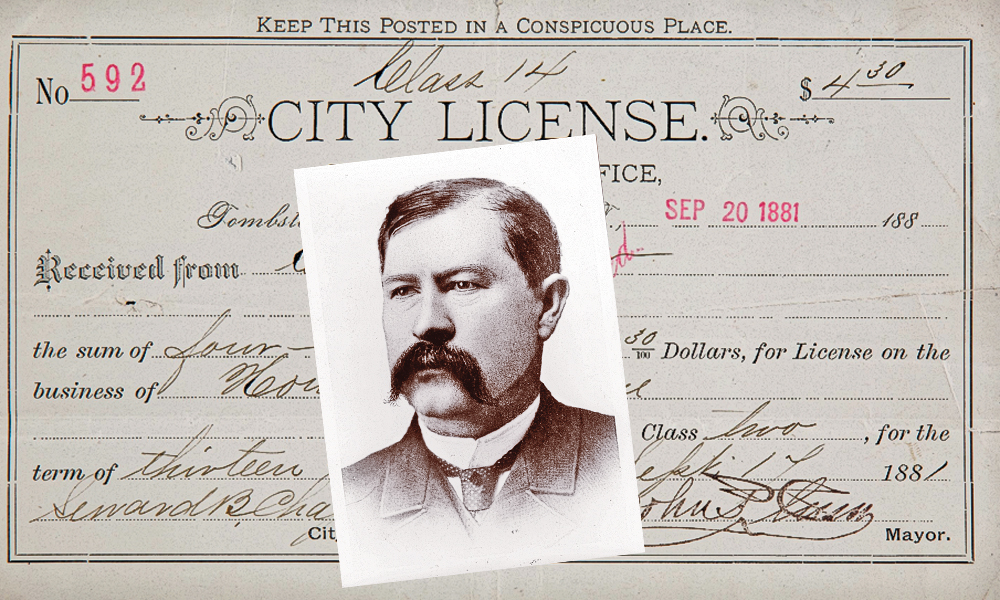

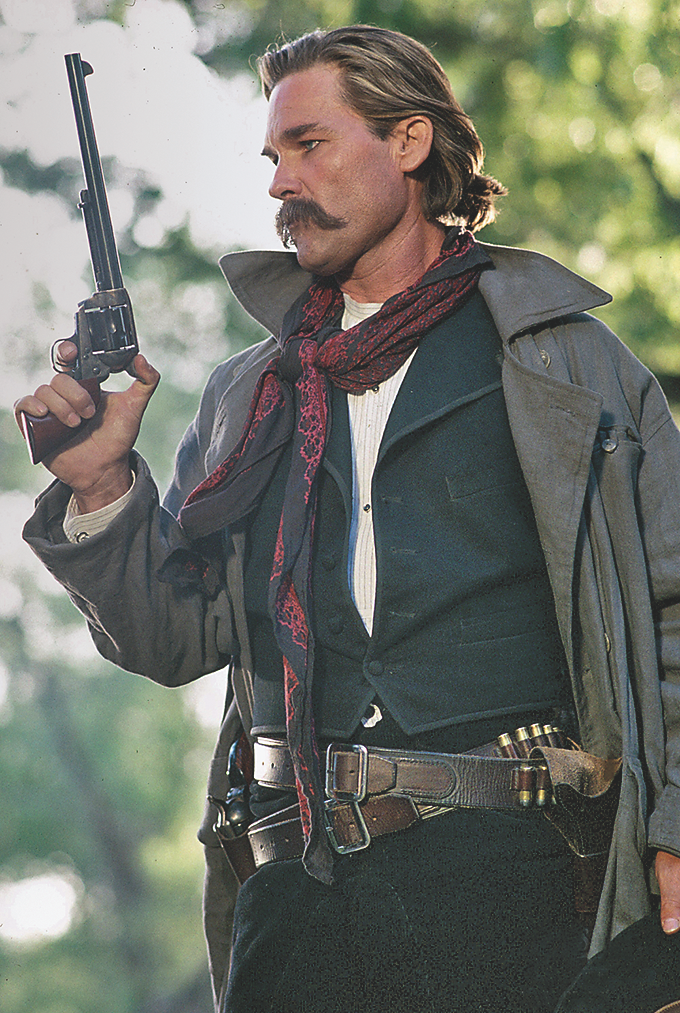

Wyatt Earp.

What Could Have Been

Kevin Jarre’s original script is stunning and haunting. Had that film been made, it would stand out as perhaps the greatest of the genre. It would also have been very, very long. Would it have captured the imagination in the way that the actual film did? I can only guess, but I somehow doubt it. The current version of Tombstone is a film people can watch over and over, repeatedly enjoying it. Not many films can make that claim.

—Casey Tefertiller (Author of Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend)

Anyone in Hollywood Listening?

If Kevin Jarre had been able to film his own script, it would have made Scorsese’s The Irishman looks like a trailer. It’s a great script—I think somewhere I called it “the great unpublished Wyatt Earp novel”—but we’re not talking feature film, we’re talking miniseries. Kevin just had too much to say. Some of the deleted scenes that were re-inserted on the DVD give us an idea of how much richer the story would have been. For example, as Doc leaves Kate to ride with Wyatt on his vendetta, he echoes Frankie Lane’s song to ask her “Have you no kind word to say while I ride away?” Perhaps the best example is the scene someone sent me on VHS where Billy Clanton swipes Wyatt’s horse and Kurt Russell rides out to the Cowboy camp to retrieve it. We actually get to see what it is the Cowboys do: rebranding stolen Mexican cattle. Particularly interesting is that in real life, Wyatt went out to the camp without a gun.

Tombstone is pretty good as it is, but Jarre’s script is so much more layered and expansive. Come to think of it, it really would make an excellent miniseries.Anyone in Hollywood listening?

—Allen Barra (Author of Inventing Wyatt Earp: His Life and Many Legends)

A Misguided Vision

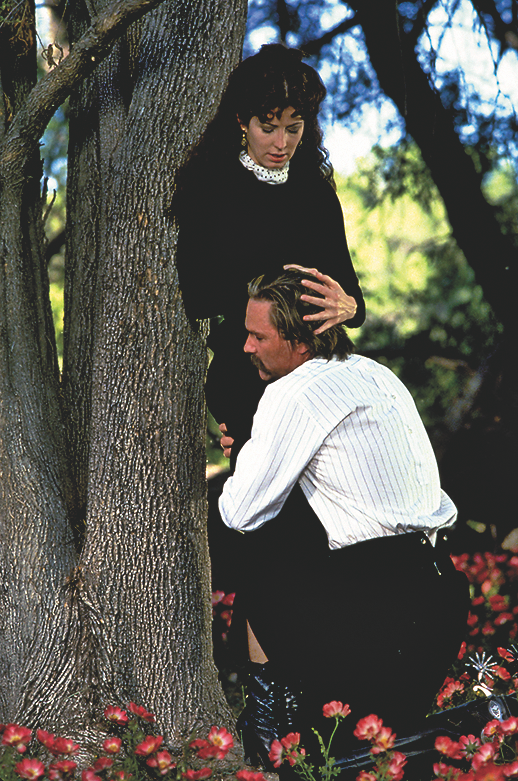

While Kevin’s pre-production period was one of the more thorough and detailed of productions I have worked on (selection of wardrobe, boots, hats, weapons), I was surprised at his shot selection choices and his sense of composition. During the first few days of shooting (if not the actual first day of shooting—memories get confused) Kevin lined up a shot with Wyatt and Josephine when they “meet cute” before their challenging horse race through the woods and down a steep drop.

The way it was staged Josephine towered a full foot and a half over Wyatt’s head. In no one’s book is this a proper composition that would show two equally strong personalities meeting privately for the first time. We all saw this as a problem. I asked Bill Fraker (the director of photography and associate producer) if I was wrong and he agreed and said he would talk to Kevin. He did. Kevin would not change the composition. I asked Terry Leonard to have a word as well (both men were highly respected in their fields and as directors as well). Again Kevin argued to keep his composition.

I will not speak for Kurt Russell, but I felt that he was not happy at “looking up” to Josephine at such an awkward angle—so I too talked to Kevin. He told me that he intended to do such novel compositions throughout the film and that his style would not be MTV music video—but John Ford.

I knew we were in trouble but hoped that as time progressed Kevin would pay attention to Billy Fraker and come to an understanding of how the composition of a shot tells the same story as the dialogue does, if not more.

That never happened in spite of the efforts of many people to convince him. While Kevin was still directing and after the change of directors, Cinergi was accused of taking a classic American Western and turning it into a music video Western. That was meant as a slam, but if you look at the final cut of the movie, while there is some MTV-style cutting, in the end it all works together. If Kevin had stayed on, there would have been mighty battles in the cutting room after his first cut.

Andy Vajna at Cinergi, I am almost certain but have no documentary evidence, had final cut rights to the movie. He and his partner at the time at Carolco—Mario Kassar—successfully cut a teaser/trailer of First Blood after an initial viewing proved less than welcome with Sylvester Stallone. That teaser went over HUGE at Cannes, and the picture was cut using the style that was created in that editing room.

Revenge motif was a best seller for Carolco. A wronged person sets out to right that wrong and is willing to die in the attempt. Many of Carolco’s films featured an armed hero/star with a weapon in a posture of combat against a background of red. In Tombstone it was the burning building on the main street with the four armed heroes in black marching into history.

I think Andy would have gotten intimately involved in the editing had Kevin completed the film, and I would bet that his version would have been significantly different from the one Kevin had in mind. This is hindsight on my part and conjecture, but I knew both men and I know that Andy would have won.

—Bob Misiorowski (Tombstone producer, shared credit with Sean Daniel and Jim Jacks)

The Greatest Western?

If one disregards the over-the-top bloodbath scenes in its first five minutes and its final 15 minutes, Tombstone may well be the finest Western ever filmed. Its sets, costumes, casting, acting and especially the extraordinary screenplay by Kevin Jarre, place it far beyond any other motion picture about the Old West. When it first appeared in 1993, some critics pooh-poohed the sets and the clothing. Western sets were supposed to look like ghost towns, and male actors were supposed to wear batwing chaps, huge Stetson hats and buscadero holsters. But critics and viewers alike soon understood the truth: mining towns like Tombstone were then new; batwing chaps, huge Stetson hats and buscadero holsters did not exist in the Old West; and people in that era wore clothing exactly like that seen in Tombstone.

Much of that authenticity came from the expertise of its technical consultant, Jeff Morey. His input also contributed to the fact that the script, though fictionalized, nonetheless provided a reasonably accurate account—at least by Hollywood screenwriter standards—of Wyatt Earp’s war against the Cowboys. Yes, there are wild fabrications, such as the killing of John Ringo by Doc Holliday, but also a realistic reimagining of the Earp women as former prostitutes—which modern research has confirmed. One of the most impressive features of the film is Jarre’s carefully crafted dialogue—the actors employ colorful 1880s slang with an easy abandon. Those who have not seen Tombstone are in for a real treat.

—John Boessenecker (Author of Ride the Devil’s Herd: Wyatt Earp’s Epic Battle Against the West’s Biggest Outlaw Gang)

Lost Possibilities

In terms of Kevin Jarre’s Tombstone script, that original treatment has been about as mythologized as the original events themselves. “It was Shakespearean!” “The most historically accurate telling of the Tombstone tale!” “A lost masterpiece!”

Hold your horses, folks. It was a great script, and it was the reason that many of the actors signed on to the project. Kevin Jarre had a vision, and here it was embedded. But it was Hollywood, not history. It was modern popular culture, not The Bard. Things were lost when Kevin was fired and Kurt Russell took over—including scenes that added flavor and continuity to the story. Certain characters were not as developed as they would have been if the original script had been maintained. But the truth is this: the Jarre treatment was not producible, not within the confines of a two-hour movie. Not within a somewhat reasonable studio budget. That’s the hard reality. But the legend is more interesting, fraught with lost possibilities and a masterpiece unmanned. So let the horses run.

—Mark Boardman (Features Editor of True West and editor of The Tombstone Epitaph)

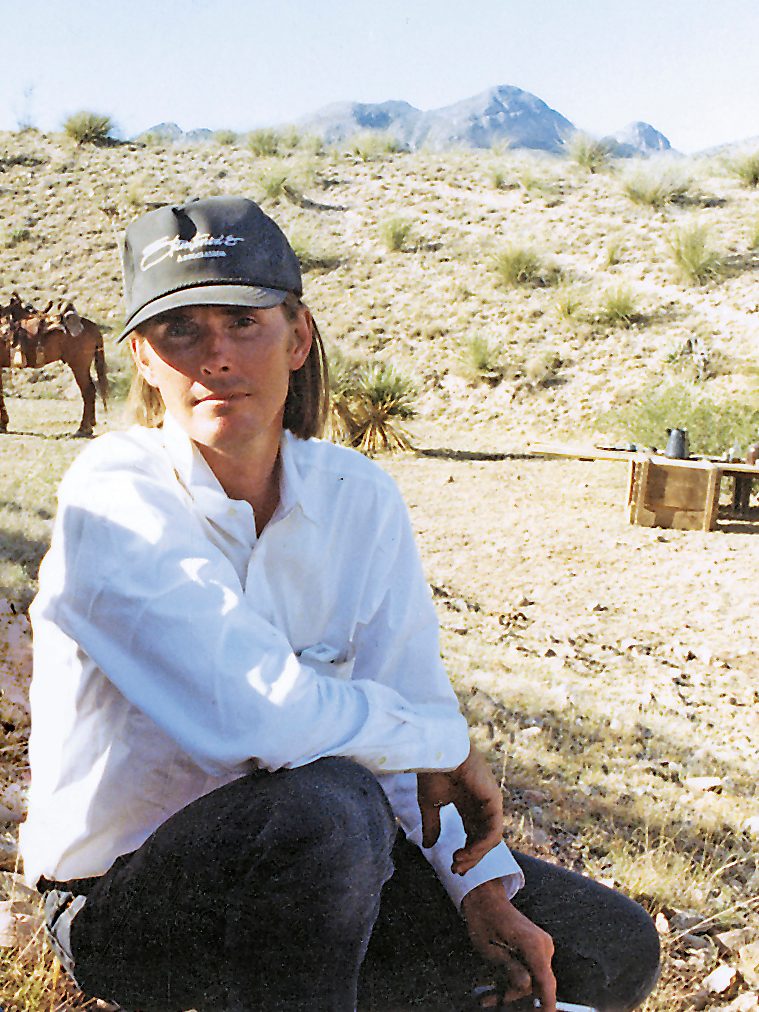

Kevin Jarre

The Man who Created Tombstone

By Henry C. Parke

Born in Detroit in 1954, Kevin Jarre had a tumultuous youth, which predestined him for a cinematic career. The son of gorgeous 1960s starlet Laura Devon, he lived first in Wyoming with his “Hemingwayesque” biological father, Cleland Boyd Clark, a rancher and fashion photographer. After moving to Hollywood with his mother, he was soon playing bit parts in Flipper, alongside series star (and now Kevin’s stepfather) Brian Kelly. By 1967, Devon had shed Kelly and wed French film composer Maurice Jarre, who’d won Oscars for Lawrence of Arabia and Dr. Zhivago. Maurice adopted Kevin.

As a teenager in England, where Maurice was scoring Ryan’s Daughter, Kevin befriended the film’s director, David Lean, who scoffed at the lad’s plans for an acting career, encouraging him instead to write and direct, and to skip film school. “He said I could learn all that in six months.”

Jarre was writing spec scripts, “living on dog food at the time,” when he got his break: He was hired to write Rambo. A spec script became The Tracker, an HBO Western starring Kris Kristofferson. He says he was a “Civil War freak…ever since I got some toy soldiers when I was a kid,” and that a friend’s comment that Jarre resembled Robert Gould Shaw, the white Harvard grad who led the all-black Massachusetts 54th in the Civil War, led to research, and the film Glory, which won three Oscars.

Then came Tombstone: Jarre’s brilliant retelling of the O.K. Corral gunfight became not merely a classic but the career zenith of virtually everyone associated with the film. It was to have been his directorial debut, but sadly, unable to direct at a pace to match the film’s shooting schedule, he was replaced. He followed with the I.R.A. thriller, The Devil’s Own, and shared story credit in the 1999 hit, The Mummy. Though, tragically, Jarre died of heart failure at the age of 56, the legacy he left, with Glory and Tombstone, is more than sufficient to guarantee him film immortality.

Truth in Black and White

By Michael Biehn

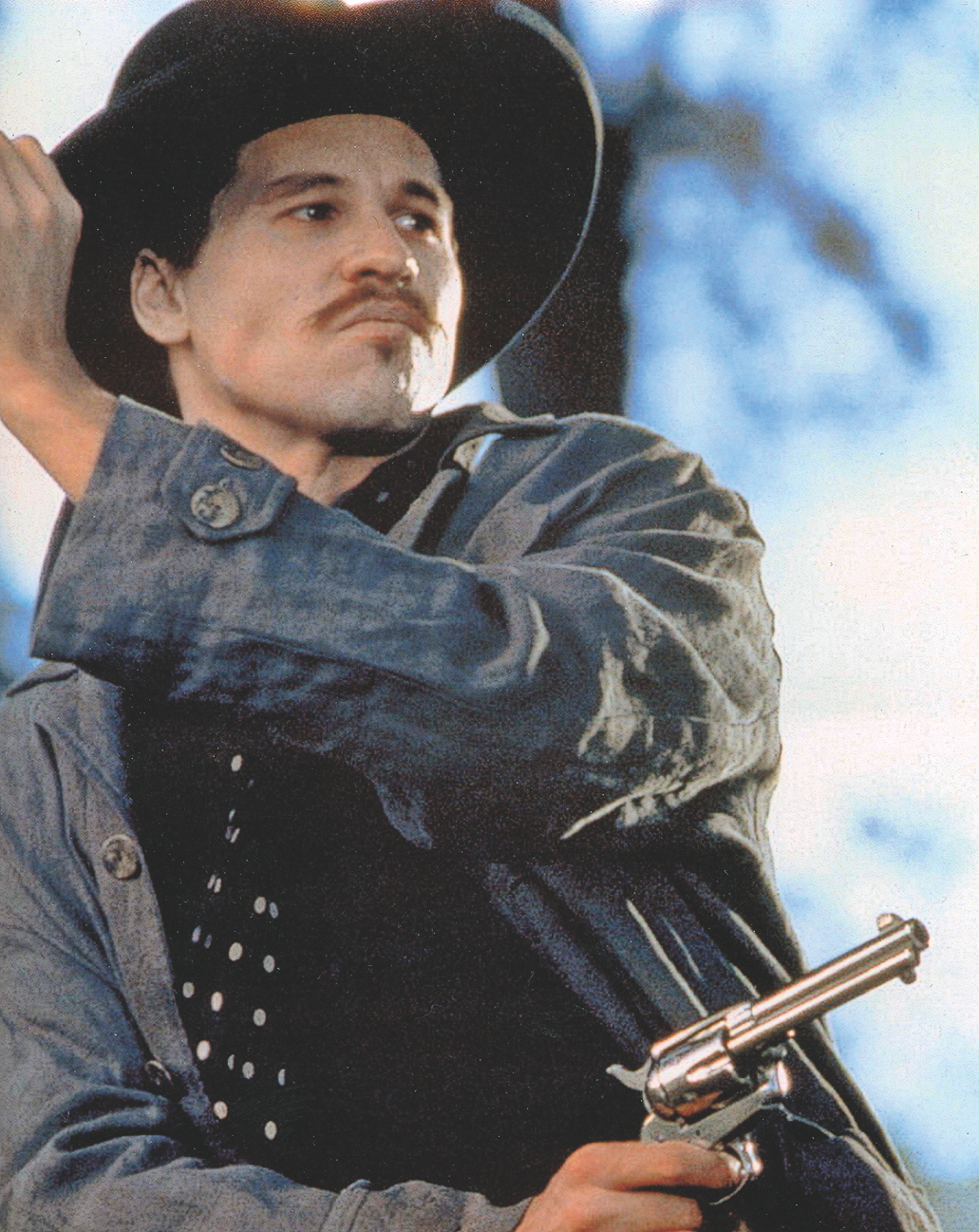

The multitalented actor who played Johnny Ringo in Tombstone reflects on Kevin Jarre’s script and the film’s production.

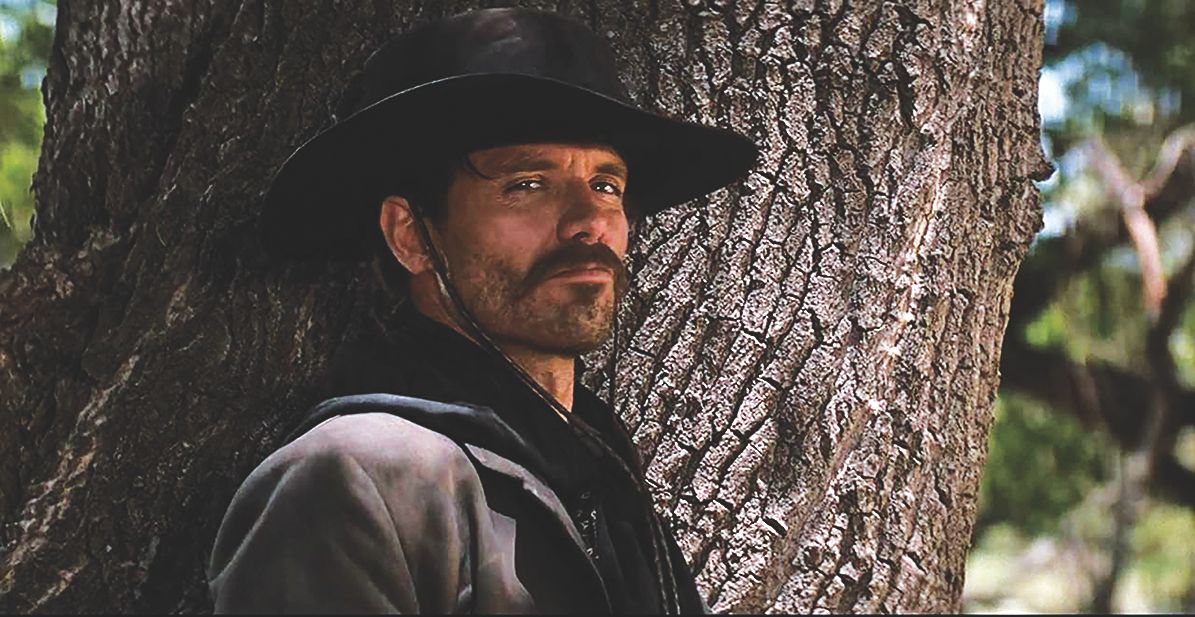

About two years ago my wife and I decided we would spend more time in Arizona. We selected a home in historic Bisbee, drawn by its small-town, artisanal character. Bisbee also lies within close proximity of Tombstone, setting of the 1993 movie in which I played Johnny Ringo.

I’d agreed to play Ringo, and I tried to envision the case he would make for himself, to grasp his reason for being. I didn’t approach him as a “bad guy” per se; actors don’t play bad guys; they play characters in situations. It helped, too, how much the other characters built up Johnny as the fearsome antagonist: “The deadliest pistoleer since Wild Bill,” Doc calls him in their first scene. And near the end, on the night of the final showdown, Doc and Wyatt wax eloquent on what makes a man like Johnny tick: “Got a great empty hole right through the middle of him and no matter what he does he can’t ever fill it…he wants revenge.” “For what?” “For being born.” After a buildup like that, I didn’t have to do a whole lot more than just show up.

That was why I objected to a scene in the screenplay following Johnny’s “I want your blood!” drunken howl. Curly Bill whisks Johnny off to a ranch house, clearly intent on raping the woman inside, and leers “See, Johnny, there is a God.”

Overkill, I protested. Johnny’s villainous persona is already established by now; if shooting a Catholic priest at a wedding hadn’t accomplished that, it’s hard to imagine what would. And I felt demonstrating Johnny’s knowledge of the Bible and Latin prior to shooting the priest suggested a backstory involving the church that gave him grounds for his actions.

That “See, Johnny, there is a God” line didn’t survive to the final film; we never shot it. All movies undergo screenplay modifications prior to and during production as well as through editing, this was just one of many cuts. In fact, the story-behind-the-story of Tombstone is just how severely the screenplay was “modified” when screenwriter Kevin Jarre was dismissed as director weeks into production. Whole sequences went on the chopping block during the hectic weekend following Kevin’s departure, when the fate of the production hung in the balance.

Kurt Russell talked in these pages (True West, October 2006) about what he and the producers faced in determining what would remain of the screenplay, a dilemma made even more difficult by the decision to not use any of Kevin’s footage. Kurt talked about how much he had to pull down from Wyatt’s scenes to give the other characters breathing space. The Cowboy roles also underwent severe cuts; Powers Booth and I lost meaty scenes and fifth credited Robert Burke (Frank McLaury) barely has any lines or screen time in the movie.

I had long believed that after Kevin’s departure, Tombstone lost the depth of his original vision; that the shadings and nuances of the primary figures had been stripped away and what remained were the familiar, stereotypical caricatures of the standard Western. I’m sure my identification with Ringo and my bonding with the actors playing other Cowboys put blinders on me and rendered my memories myopic. I’d come to believe that Kevin’s almost fanatical desire for historical accuracy in matters like wardrobe and weaponry meant that his screenplay was similarly accurate in depicting the fullness of its characters.

I’d come to believe that with such certainty that I recently did something I’ve never done before—dug up a copy of the version of Tombstone I first read 30 years ago. I don’t watch my old movies—the “willing suspension of disbelief” just isn’t there for me—let alone reread the screenplays. But filled with what I’d been reading and fired by the conviction that Kevin had tried to tell a truer story than all the previous versions by far, I began reading.

There was a comforting old familiarity in the screenplay’s opening lines, Robert Mitchum’s voice intoning the opening monologue. Mitchum had been cast as Old Man Clanton in the first scene, but injury kept him from filming, so he narrated instead, and the Old Man went to an early grave as Curly Bill took his best lines. I was fortunate to get the screenplay early, and the caliber of the cast that came together would be among the best of any film of the decade, I would argue, a testament to the screenplay’s quality. “Godfather of Westerns,” it’s been called.

My first thought after putting the screenplay down after rereading it, however, was “What just happened?”

This wasn’t what I remembered at all. That subtlety and nuance, that balanced presentation of the characters I’d persuaded myself was the bedrock of Kevin’s screenplay, never existed. Kevin went all in showering the Cowboys in villainy at every turn while exalting Wyatt into an avenging angel Frontier Dirty Harry.

The Wyatt lionizing reaches a high-water mark in a scene near the end during the vendetta ride. Wyatt stumbles upon a wagon train filled with fellow Illini, who hail him without knowing anything about him, a sequence that ends with a nod to a classic Western with a little boy calling after him something akin to “Come home, Wyatt, come home.” Cue the music. That sequence never got shot, as was true of much of the screenplay’s last third, which included subplots drawing out the vendetta ride into a meandering marathon.

I thought when I got to page 90 that I must be nearing the end and gasped when I saw there were still 40 more pages!

In his True West interview, Kurt Russell said he often urged Kevin to cut 20 pages, and I’m sure he was referring to this material since much of it went with Kevin. Wyatt lost some nice moments—he had plenty—and Johnny lost a rousing version of a “St. Crispin’s Day” oration taking command of the Cowboys in the aftermath of Curly Bill’s demise “ … This is my time, children. This is where I get woolly.”

One significant discovery for me was how much fuller the women’s roles had been; I hadn’t appreciated just how severely they’d been emptied out with the screenplay cuts. Josie (Dana Delany) was an integral player in Tombstone history as well as in the screenplay. She was first engaged to Sheriff Behan before fixing her eyes on Wyatt, and the ensuing romantic triangle contributed to the tensions that resulted in the gunfight.

With Kevin’s departure, Josie’s screen time was so scaled back that any reference to her involvement with Behan disappeared, and her relationship with Wyatt amounts to little more than a chance encounter on horseback. A tense scene with Josie and Mattie Earp vanished, along with just about any other presence of the Earp wives. In the screenplay, Big Nose Kate’s repartee was every bit the match for Doc Holliday’s wisecracks, but in the movie she’s little more than an adorning onlooker.

Without question the biggest eye-opening takeaway for me in the screenplay is just how strenuously Kevin pushes the “depraved” label on the Cowboys. My illusions about “nuance” and “shadings” got put to rest right from the start with this now-deleted definition of Cowboy—“an insult implying deviant sexuality.”

From there follows a palpable homoerotic undercurrent amongst the cowpokes, almost as though they were a crew of “gay caballeros” and Curly Bill’s frequent protective arm around the shoulder of “Sister Boy” Breakenridge (Jason Priestly) suggests they may have strayed off to Brokeback Mountain a time or two. This “sexual depravity” element feels like a dead horse the screenplay insists on flogging, one of several the film didn’t need or use.

Clearly, then, no one has a monopoly when it comes to myth-making and truth-bending; there’s a veritable glory hole of it surrounding tales of Tombstone. I didn’t realize how in my “misremembering,” I’d mythologized Kevin Jarre’s screenplay into something he never intended it to be. Kevin very much followed the Liberty Valance dictum that “when legend becomes fact, print the legend.” The movie that emerged after his departure is a boiled-down version of what was always in the screenplay and not some compromised artistic vision. The irony is in no way lost on me that for months now I’ve been advocating for a greater embrace of “the truth about Tombstone” while at the same time remaining so oblivious to the truth about something I should have known all along. Wouldn’t be the first time.