“Uncle Dick” Wootton helped build a nation with his Santa Fe Trail toll road.

Well past midnight, everyone in the wagon train was snoring. First night on guard duty, teenager Dick Wootton spotted a stealthily approaching shadow in the chest-high grass. Convinced Indians were about to attack, he propped the large-bore rifle against his shoulder, sighted down the barrel and pulled the trigger. The shadow dropped. Heart pounding, he knew tonight would be memorable since he single-handedly had saved the entire Bent/St. Vrain wagon train from certain death. Except it wasn’t a sneaking Indian. The lead mule, Jake, had wandered off and was simply returning to camp. Wootton never did live that down.

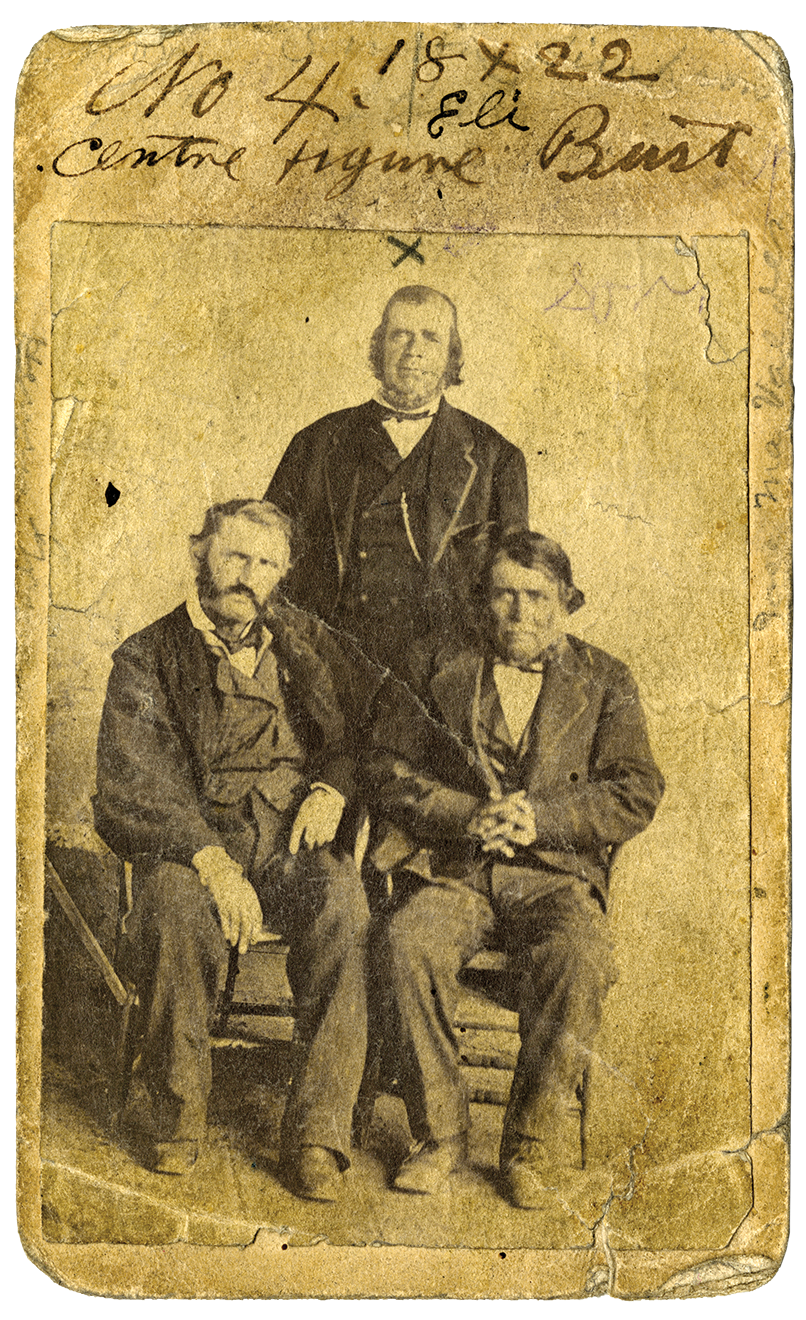

In 1836, he began a lifetime as a frontiersman, adventurer, trapper, guide and businessman. Always seeking adventure, “Uncle Dick” Wootton is best known as the tamer of Raton Pass. Wootton fought and traded with Indians, trapped and scouted the Western half of the country. He led wagon trains, herded buffalo, cattle and sheep, farmed and ranched and ran a stage stop in Trinidad, Colorado. He also constructed and operated a toll road across the mountains from Trinidad to Willow Springs (now Raton), New Mexico.

Born Richens Lacy Wootton on May 6, 1816, in Virginia, he was seven when the family moved to Kentucky. At age 17, Richens moved in with an uncle on a Mississippi cotton plantation. But he needed more excitement. Within two years he moved to Independence, Missouri, and signed on as a wagon man. For years he hauled freight for the firm of William and Charles Bent and Ceran St. Vrain, crossing the Great Plains via the Santa Fe Trail. On that first trip, men mistook his name as Richard, so he became Dick. He acquired “Uncle” years later in Denver when he tapped two barrels of his Taos Lightning for appreciative miners.

Raton Pass

Through the years, he successfully achieved many firsts, including opening a hotel, restaurant and dry goods at a Colorado gold camp, in what is now Denver. But he’d harbored a desire grander than that. His many trips from Pueblo, Colorado, south into Fort Union and Santa Fe, New Mexico, had proven that a better, faster, safer road was vital to traffic on the Santa Fe Trail. This route was a commerce highway opened by merchant William Becknell who correctly foresaw profits being made in transporting American goods across prairies to appreciative customers in Mexico’s frontier. He used heavy Murphy freight wagons, and within a short time the Santa Fe trade ballooned into a million-dollar-a-year business.

The first official Santa Fe Trail route was surveyed in 1825 by U.S. military patrols, so by the time Wootton took that initial freight wagon train across in 1836, the trail was well-used. Travel had blossomed once Spain, which would not trade with the U.S., lost ownership of Mexico in 1821. Trade increased further in 1848 when the Southwest came under American rule after the Mexican War. Travel and trade from Franklin, Missouri, to Santa Fe exploded. In May 1849, the first stagecoach line began monthly service between Independence, Missouri, and Santa Fe.

Building the Pass Wouldn’t be Easy

The 7,834-foot Raton Pass, named for imposing Raton Peak, was considered an obstacle to avoid at almost any cost. Most Santa Fe Trail traders chose the shorter, more level and faster Cimarron Route, despite the threat of Indian and Texian attacks. However, the severe lack of water on that route turned many travelers to The Pass. Since 1821, when Becknell hauled the first wagon destined for Santa Fe over The Pass, the difficulty remained legendary.

Susan Magoffin, traveling with her Army husband and one of the first women to traverse The Pass, wrote in 1846: “Worse and worse the road! They are taking the mules from the carriage this p.m. and half a dozen men, by bodily exertions, are lowering them down the clifting hills. And it takes a dozen men to steady a wagon with all its wheels locked… We came to camp about half an hour after dusk, having accomplished the great travel of six or eight hundred yards during the day.”

Getting through the mountains was critical. During the Civil War, Raton Pass proved to be an important link between the Southwest and the Union, especially from 1861-62. Fear of Confederate raiders from Texas and increased Indian hostilities had forced a virtual abandonment of the exposed Cimarron Cutoff. It was through The Pass, shielded by the Rocky Mountains, that freighters continued to supply food and munitions to the isolated Union troops in New Mexico.

Taming the trail, which began as an Indian route, was no small feat. Wootton wrote in his memoir, “The hills are broken, rock-bound and ragged. Some are brown and bare; others are covered with a thick growth of shrub oak, piñon and mesquite, while there are still others crowned with groves of always verdant pine.” Narrow, wooded valleys were sprinkled throughout. It was almost impossible for anything but saddle horses and pack animals to travel the route at any time, and impassable for wagon trains or stagecoaches in winter.

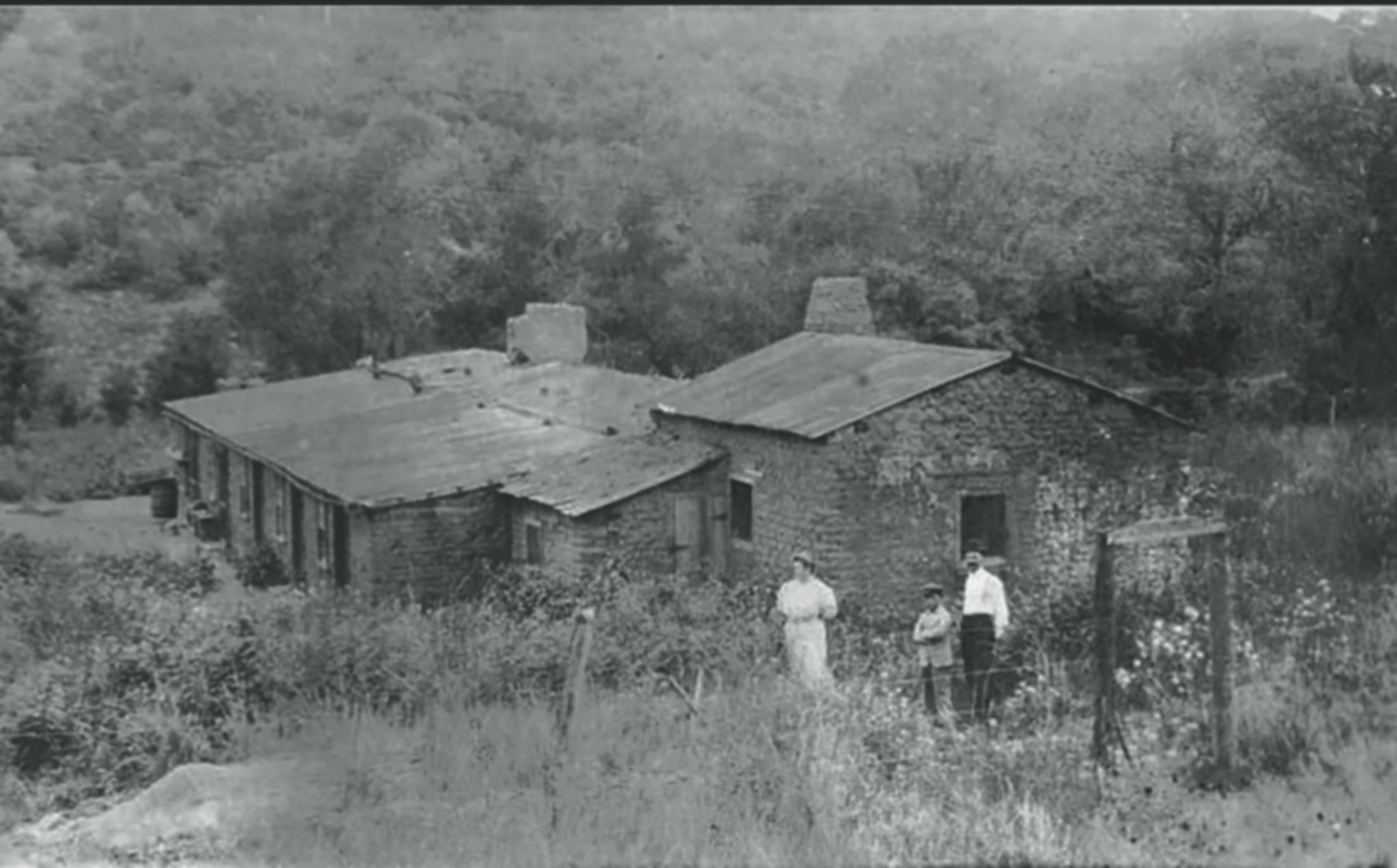

Following his dream of building a useful road, in 1865 Wootton received charters from both New Mexico and Colorado territories to build one. In spring 1866, he moved his family to Raton Pass and chose a site for his house—the bottom of the steepest part on the Colorado side.

Wootton hired engineers and surveyors. As most local men thought the work too hard, he employed a tribe of Utes under Chief Conniach. The Indians, using hard physical labor, improved 27 miles of the toughest part of the road. “I had undertaken no light task, I can assure you,” Wootton wrote. “There were hillsides to cut down, rocks to blast and remove, bridges to build by the score. I built the road, however, and made it a good one, too.”

Taking a Toll

Needing some way to pay for the construction and, of course, to make a profit, Wootton established it as a toll road. He charged $1.50 for one wagon, 25 cents per horseman, five cents per head of livestock. There were two exemptions to the toll. Indians passed through for free because Wootton knew they wouldn’t understand why they should pay to pass through their own area, and, after all, the Utes had helped build the road. Lawmen chasing fugitives were also exempt. A time or two Wootton even helped authorities by reporting who had passed through.

Travel on Wootton’s toll road increased in November 1867 when gold was discovered in New Mexico’s Moreno Valley and a daily Barlow and Sanderson stage route was established. Although Wootton kept no accounts of the receipts from his road, his partner George C. McBride did. Between April 1, 1869, and April 1, 1870, McBride recorded receiving $9,196.64 ($185,952 in today’s dollars).

As stagecoaches began to rumble through the pass, Wootton quickly converted the house into a hotel, restaurant and bar. “You couldn’t run a stage station without a bar,” he wrote, “so I had one.” Many evenings were spent around the fireplace with Wootton telling stories of his wilder days and stage passengers relating their latest scary traveling tales. The hotel became so popular, people from Trinidad and El Morro held dances there every week.

One of the ranches next to Wootton’s belonged to Scottish immigrants—the Smith brothers, William, Hugh and John, who went by the monikers Poke, Hoke and Joke. Wootton, the Smiths and neighboring ranchers rounded up their herds into Tin Pan Canyon, then sorted them out to brand them. One of Poke’s sons often acted as designated driver for Wootton when he wanted to go into Trinidad and have a “gay ol’ time.” The Smith teenager would wait outside the saloon with a buggy and then haul an inebriated Uncle Dick home safely.

And Then the Railroad Came

In 1878, progress came knocking at his door. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad offered to buy Wootton’s toll road right-of-way through Raton Pass.

Uncle Dick realized he was no longer the spry man he’d been. “The railroad took the place of the stage line,” he reminisced. “And since that time, I have lived in a different atmosphere from that in which I formerly lived. I almost feel I am no longer on the frontier and that there is no frontier to go to.”

Reluctantly, he agreed to sell his toll road and move to Trinidad. Initially, the railroad offered him $50,000 ($1.3 million in today’s dollars), but he turned down the deal, asking instead for only $1, unrestricted train travel for his wife and him, and grocery money for his wife’s lifetime. They agreed on $25 per month for Maria Pauline Lujan Wootton, 40 years his junior. After Uncle Dick’s death in 1893 at age 77, Maria continued receiving the agreed-upon benefits. In 1925 the Santa Fe Railroad doubled the payments and in 1930 increased them to $75. After Mrs. Wootton’s death in 1935, an invalid daughter received $25 a month during her lifetime.

It wasn’t until 1980 that the two-story ranch house at the base of The Pass was torn down. Over his lifetime, Dick Wootton married at least four times and sired 20 children. He outlived all but one wife and three children. He is buried in Trinidad, Colorado.

Navigating the Pass

Today, the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway rolls over Wootton’s pass. Interstate 25 often parallels the train route. An early Raton Pass road built for autos and parts of the original SFT can be traveled by heading up Moulton Avenue in Raton. The street makes a sharp left, then bends right and starts up a switchback road to the top of the mesa. The road is barricaded about halfway with no access to the private property on the other side. The pavement is in poor repair and because there are no guard rails, the drive should not be attempted lightly. Photos of Model Ts with gravity gas tanks backing up The Pass are on display at the Raton Museum.

New Mexico native Melody Groves loves the area where she grew up. Exploring ghost towns and riding horses sparked her Wild West imagination. Winner of numerous writing awards, she writes Western fiction and nonfiction.