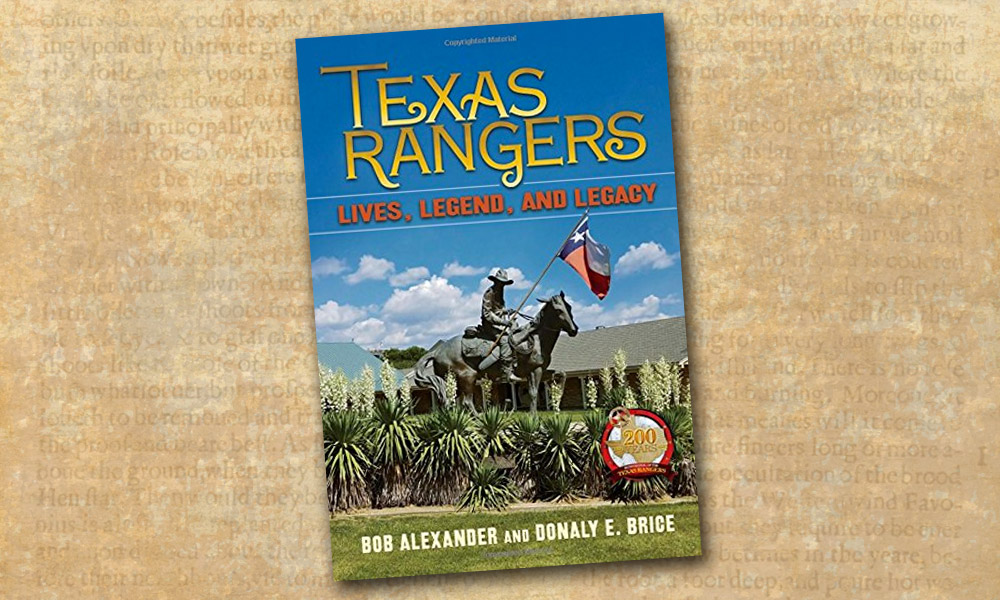

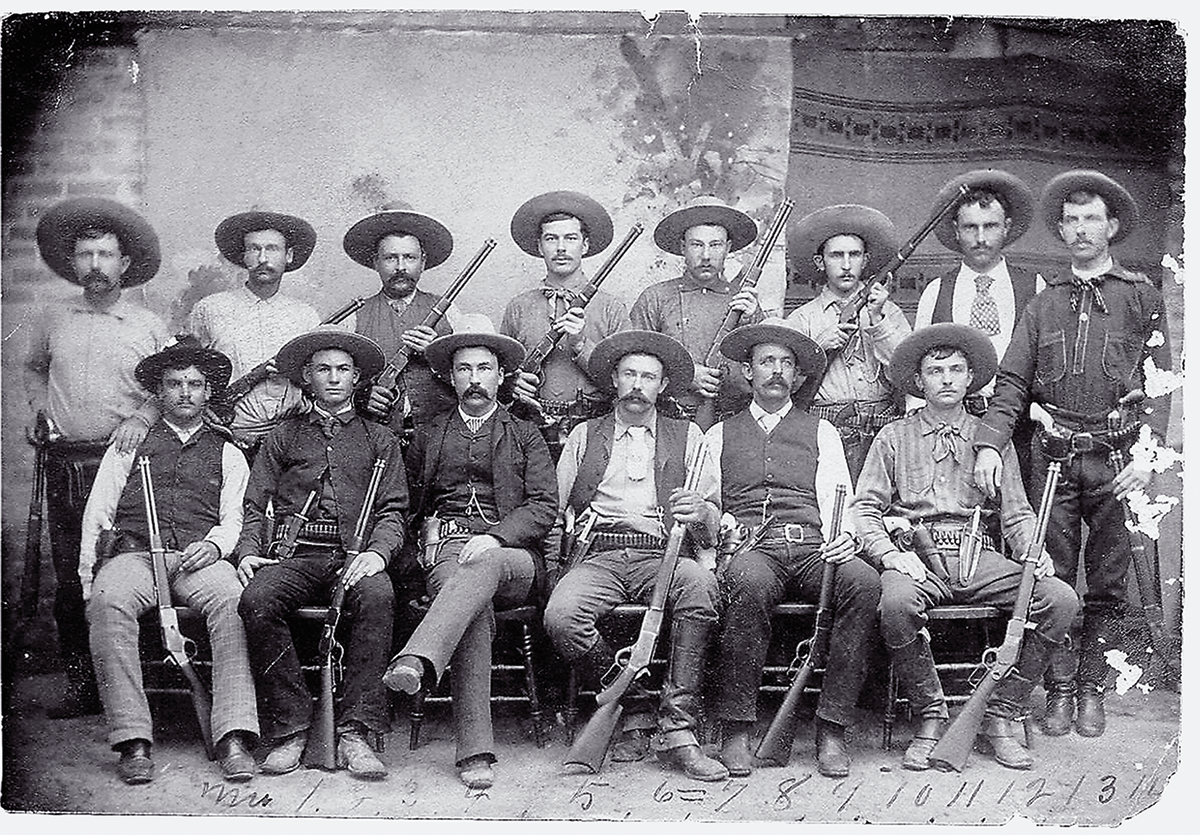

FOLLOW THE HISTORIC TRAILS OF THE LONE STAR LAWMAN THROUGH WEST TEXAS FROM SAN ANGELO TO EL PASO.

– COURTESY SAN ANGELO CVB –

“They are having a lively time in Tom Green county,” reported the March 24, 1877 Daily Fort Worth Standard. “Six murders in three months and no arrests.”

Beyond the violence in and around San Angelo, “Organized bands of stock thieves exist in such numbers, and the county is so sparsely settled, that the laws cannot be enforced…” However, help was coming: “The citizens and officers of the county have for- warded a petition to Austin to have the State send Rangers to aid the civil authorities.”

Peaceful compared to frontier times, modern San Angelo makes a great starting place for Old West history buffs hankering to saddle up and backtrail the early Texas Rangers across West Texas.

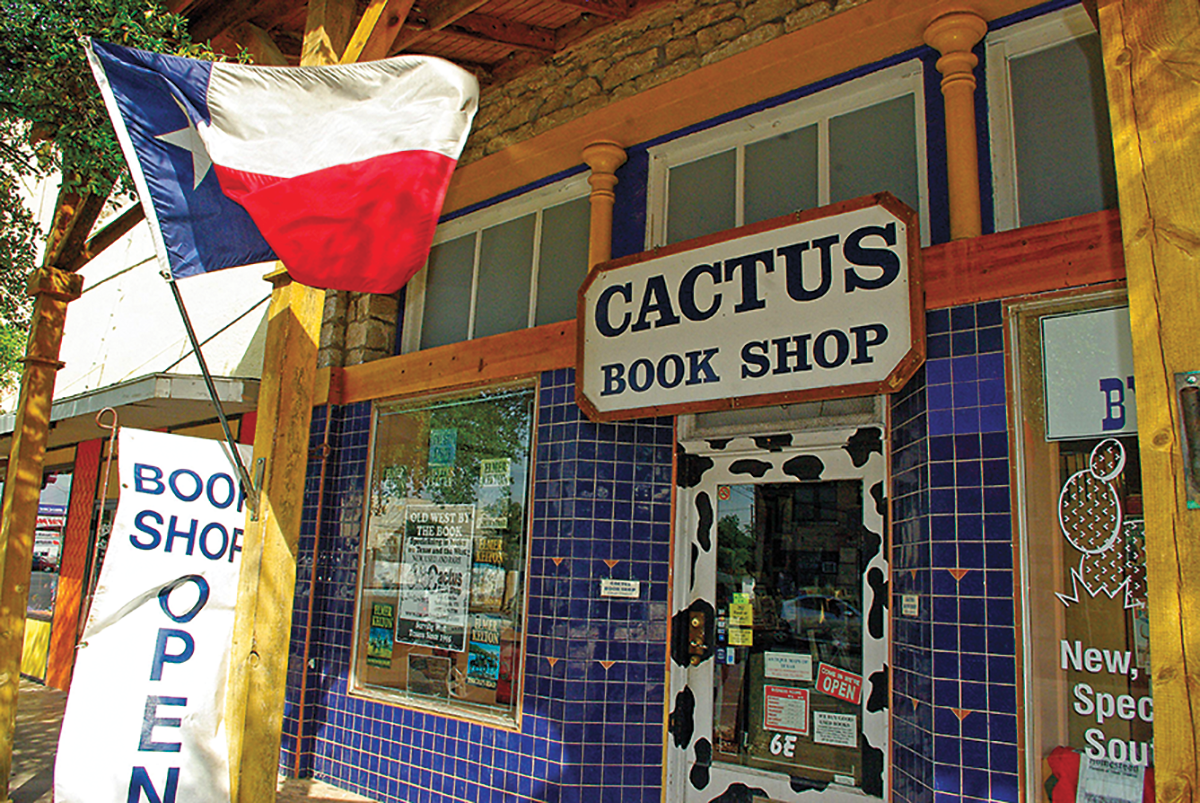

Old Fort Concho, now a National Historic Site, is one of the West’s best-preserved frontier forts. Downtown, col- orful murals depict the city’s history, and in the lobby of the public library is a life-sized statue of the late Western writer Elmer Kelton. Several of his best-selling novels fea- tured the Rangers.

From San Angelo, head west on U.S. 67, which goes all the way to Presidio. But there are some historic places to visit before you get there.

PHOTO COURTESY SAN ANGELO CVB –

West to Fort Stockton and Pecos

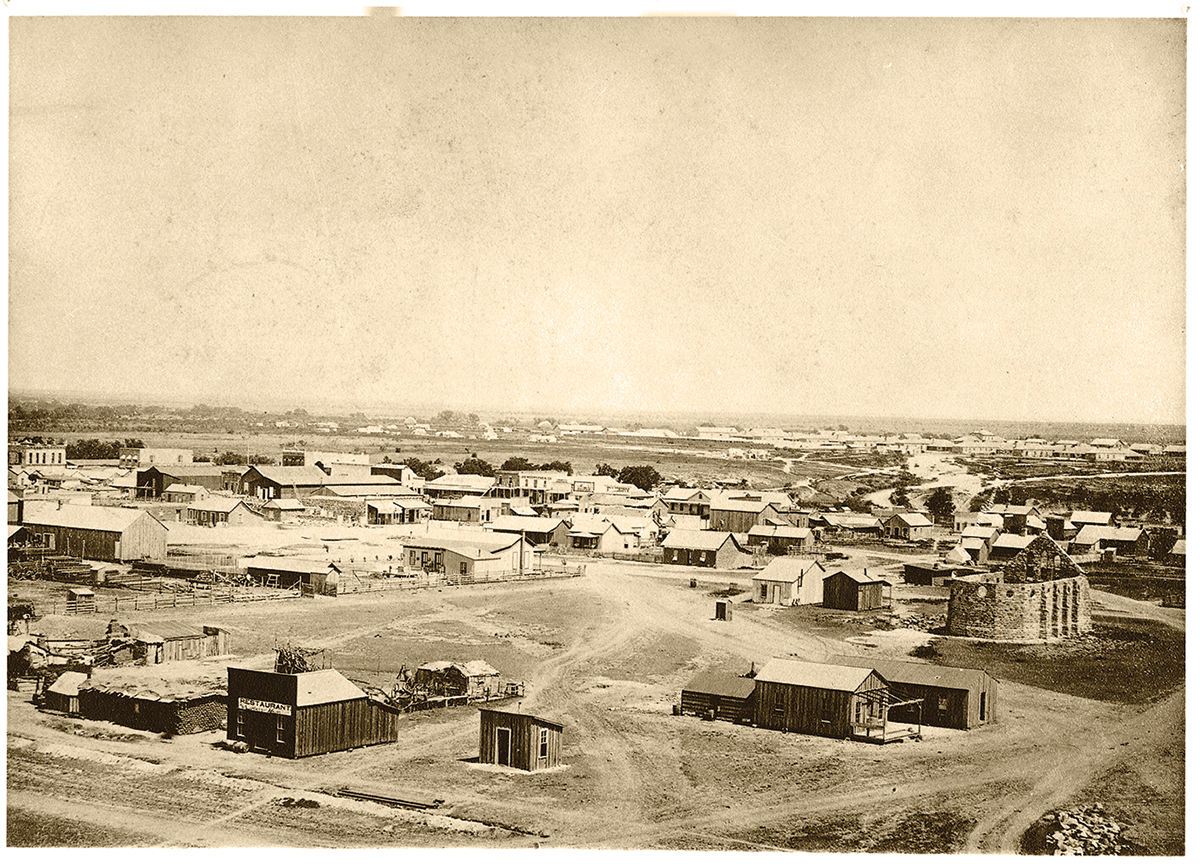

One hundred sixty-five miles southwest of San Angelo on U.S. 67 is Fort Stockton, named for the old military post standing near the once prolific Comanche Springs. The Army chose the spot because it was a watering hole along the Great Comanche War Trail.

Hostile Indians were long gone by 1894, but law and order remained a work in progress. Someone shotgunned lame duck Sheriff A.J. Royal on November 21. No arrests were made in the killing, and there were even dark rumors that a ranger might have had a hand in it. The assassination took place inside the 1883-vintage Pecos County courthouse, 400 S. Nelson Street. The desk where Royal sat when he was killed is at the Annie Riggs Museum, 301 S. Main Street. A museum dedicated to the history of the military post is in Barracks No. 1, Old Fort Stockton.

After you’ve tamed Fort Stockton, the next stop on your Ranger-channeling journey is Pecos, 54 miles away via U.S. 285. Just west of the river that gave the railroad and ranching town its name, Pecos claims to have staged the West’s first rodeo. While that’s debatable, so far as is known, no one has ever been killed over it. During the 1880s and ’90s, however, Pecos denizens had no trouble finding other reasons to shoot. Take former Ranger George Alexander Frazer and Jim “Deacon” Miller, a devout Methodist who neither smoked nor drank but ignored the sixth commandment, the one about not killing.

Frazer had served as Reeves County sheriff with Miller as his deputy, but they had a falling out. On April 12, 1894, six months after losing a reelection bid, Frazer confronted Miller in Pecos. Accurately calling him out as a cow thief and murderer, Frazer shot Miller in the arm and then put several bullets in his chest. Or so he thought. Unknown to Frazer, the Deacon wore metal body armor. Though badly bruised, he recovered.

More than two years later, on September 13, 1896, Miller found Frazer in a Toyah saloon and permanently settled the score with his double-barreled shotgun. A jury acquitted him, but his luck played out in 1909, when a lynch mob in Ada, Oklahoma, adjudicated him without possibility of appeal.

Since 1962, the former Orient Hotel and Number 11 Saloon at 120 E. Dot Stafford Street has been home to the West of the Pecos Museum. Bullet holes from a gunfight in the saloon are still visible.

Southwest to Alpine

Alpine, 67 miles farther west on U.S. 67, began as a stop on the Southern Pacific. Given the vastness of the Trans-Pecos, which covers 31,479 square miles and is larger than any one of 10 U.S. states, the railroad made the mountain-circled town particularly important for the Rangers.

In mid-1890, Company D Ranger Capt. Frank Jones made Alpine his headquarters. From there, with their horses loaded on a stock car, rangers could travel by train as far as possible and continue to the latest trouble spot the more traditional way. (Today Amtrak serves Alpine.)

You can immerse yourself in the region’s rich history at the Museum of the Big Bend. Founded in 1925, the museum is on the Sul Ross State University campus.

– JEROD FOSTER, COURTESY PECOS CVB/FRAZER PHOTO COURTESY

TRUE WEST ARCHIVES –

Alpine is the closest community of any size to history-rich Big Bend, a vast expanse where old-time Rangers did much business. One of them, Everett Ewing Townsend, became enthralled with the rugged mountains and canyons along the big bend of the Rio Grande. Later, as a state legislator and then a private citizen, he played an important role in promoting development of Big Bend National Park. The longtime lawman is buried in Alpine’s Elm Grove Cemetery.

– COURTESY BIG BEND MUSEUM –

Fort Davis, Marfa and Presidio

From Alpine, travel 24 miles on S.H. 118 to the mile-high town of Fort Davis, named after the Army post that guarded the Trans- Pecos from 1854 to 1891. The Rangers had a camp nearby from which they chased hostile Indians and outlaws. That site is privately owned, but you can immerse yourself in the area’s history at the Fort Davis National Historic Site. Another Ranger-related site is the Overland Trail Museum, located in the former home of colorful barber and justice of the peace Nick Mersfelder. The pipe- smoking German came to Fort Davis as a ranger in 1881 and never left.

It’s only 21 miles from Fort Davis to Marfa, where you can pay your respects to one of the better-known chroniclers of Ranger history, James B. Gillett. Beyond his contributions to the peace and dignity of the state as a Ranger, he wrote a classic, Six Years With the Texas Rangers. He’s buried in Marfa Cemetery, 210 W. San Antonio Street (U.S. 90). Also check out the Marfa and Presidio County Museum, 110 W. San Antonio Street, and the old (1886) Presidio County Jail, 310 Highland Street.

From Marfa, head down to the old border town of Presidio. On the way, check out the once-thriving silver mining town of Shafter, 40 miles south on U.S. 67.

Ranger John Gravis and a deputy sheriff were policing Shafter the night of August 4, 1890, when some drunk miners started shooting up the town. As the two officers approached, the pistol-packing partyers opened up on the two lawmen. Gravis fell dead; the deputy took a bullet but lived.

The mine closed in 1942. In addition to the ghost town’s ruins, check out the small museum at the Shafter Cemetery.

In 1848, San Antonio businessmen commissioned former Ranger captain Jack Hays to find a trade route to Chihuahua City, Mexico. Joined by a company of Rangers, Hays led the expedition to the Big Bend.

– COURTESY TEXAS RANGER MUSEUM & HALL OF FAME, WACO, TEXAS –

Wide Spot in the Road

The El Paso killing of John Wesley Hardin, a Methodist preacher’s son who became the Old West’s most prolific gunslinger, did not directly involve the Rangers, but none of the lawmen grieved his passing.

Released in 1894 after serving time for former ranger Charles Webb’s murder in 1874, Hardin drifted west to El Paso. He had studied law in stir, but time behind bars had not broken him of boozing, gambling or a mean disposition. On August 19, 1895, in the Acme Saloon, Constable John Selman ended Hardin’s career with three .45 slugs.

A historical marker at 227 E. San Antonio Avenue stands at the site of the old saloon. The outlaw is buried in the city’s historic Concordia Cemetery, 3700 E. Yandell Dr. At least four former Rangers eternally stand guard over Hardin at the cemetery: Capt. Pat Dolan, Ernest St. Leon (who died August 31, 1898, in a line-of-duty shooting downriver from El Paso at Socorro), Carl Kirchner and Robert Jefferson Carr.

GOOD EATS & SLEEPS

Grub:

- Miss Hattie’s Restaurant, San Angelo

- Mi Casita, Fort Stockton

- Reata Restaurant, Alpine

- Fort Davis Drug Store, Fort Davis

- The Bean Café, Presidio

- Hotel El Capitan, Van Horn

- L & J Café, El Paso

Lodging:

- Holland Hotel, Alpine

- Limpia Hotel, Fort Davis

- Hotel Paisano, Marfa

- Hotel El Capitan, Van Horn

- Hotel Paso Del Norte, El Paso

El Paso

Your Ranger-related history tour ends in El Paso, where more rangers or former rangers died violently than anywhere else. El Paso has numerous museums, but for an overview of the city’s history, start with the El Paso Museum of History, 510 N. Santa Fe Street.

The Rangers’ first trouble in El Paso came in 1877 during the Salt War, a legal dispute over salt deposits east of El Paso. Before it ended, a dozen people, including two Rangers, were dead. A historical marker in the old down-river town of San Elizario summarizes the war. Nearby is the Los Portales Museum and Visitors Center, 1521 San Elizario Road, and Old El Paso County Jail Museum, 1551 Main Street.

– COURTESY NPS.GOV –

Ranger Sgt. Charles Fusselman and former Ranger George Herold joined a local rancher on April 17, 1890, in search of rustlers who had butchered one of the cattleman’s calves and stolen some horses. With Fusselman riding ahead, they easily cut the rustler’s trail, which led into the Franklin Mountains.

That afternoon, Fusselman found the outlaws’ hastily vacated camp. As the sergeant looked around, a rifle bullet from the rocky ridge above zinged past his head. Yelling a warning, Fusselman began firing at the ambushers. An instant later, the Ranger lay dead. Realizing the outlaws had the high ground and good cover, Herold and the rancher hurried back to El Paso for help.

A larger posse rode to the canyon and recovered Fusselman’s body and most of the stolen horses, but the outlaws escaped. Ten years later, after Rangers finally caught up with him, triggerman Geronimo Parra hanged for the murder. A historical marker telling how Fusselman Canyon got its name stands off Woodrow Bean Transmountain Road (S.H. 375), 2.5 miles west of U.S. 54.

– FORT LEATON COURTESY LIBRARY OF CONGRESS/JOHN COFFEE HAYS PHOTO COURTESY LIBRARY OF CONGRESS –

On April 6, 1894, Ranger Joe McKidrict heard a pistol shot followed by a police whistle coming from the red-light district. Running to Miss Tillie’s Parlor, he found former Ranger Baz Outlaw drunk and waving a pistol. When the Ranger asked his former colleague to surrender his weapon, Outlaw shot and killed him. Outlaw also got off a round that barely missed Constable John Selman. At that, the constable mortally wounded Outlaw. Still, Outlaw got off two more shots, wounding Selman. The constable recovered; Outlaw did not. Miss Tillie’s Parlor stood at 307 South Mesa Street. Outlaw’s grave is in El Paso’s Evergreen Cemetery, 4301 Alameda Avenue.

Captain Jones, four Rangers, and a deputy sheriff headed downriver on June 29, 1893, for Pirate’s Island, an international no-man’s land caused years before, when the Rio Grande changed course. The rangers carried arrest warrants for two brothers, well-known cattle thieves. They also hoped to locate another brother, a prison escapee.

Finding only the wanted men’s blind father at home, the rangers pulled back and made camp. The next morning, they spotted two suspicious horsemen and gave chase, riding straight into an ambush. When the intense firefight ended, the 36-year-old captain was dead. Substantially outnumbered, the Rangers withdrew, leaving Jones’s body behind for the time being.

A historical marker summarizing the fight stands at 8461 Alameda Avenue in Ysleta. Jones’s grave has been lost, his remains believed to have been swept away by the Rio Grande.