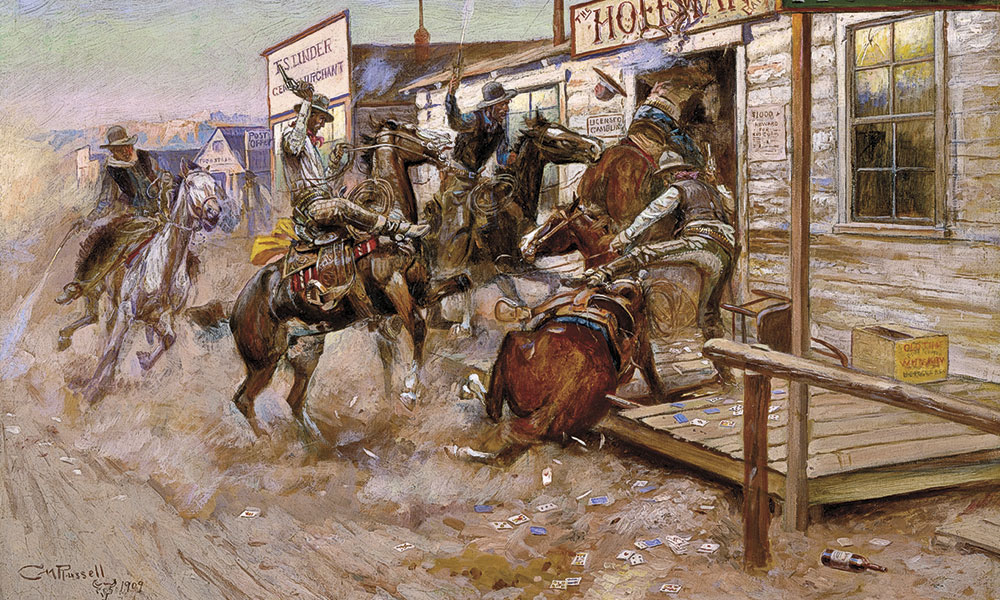

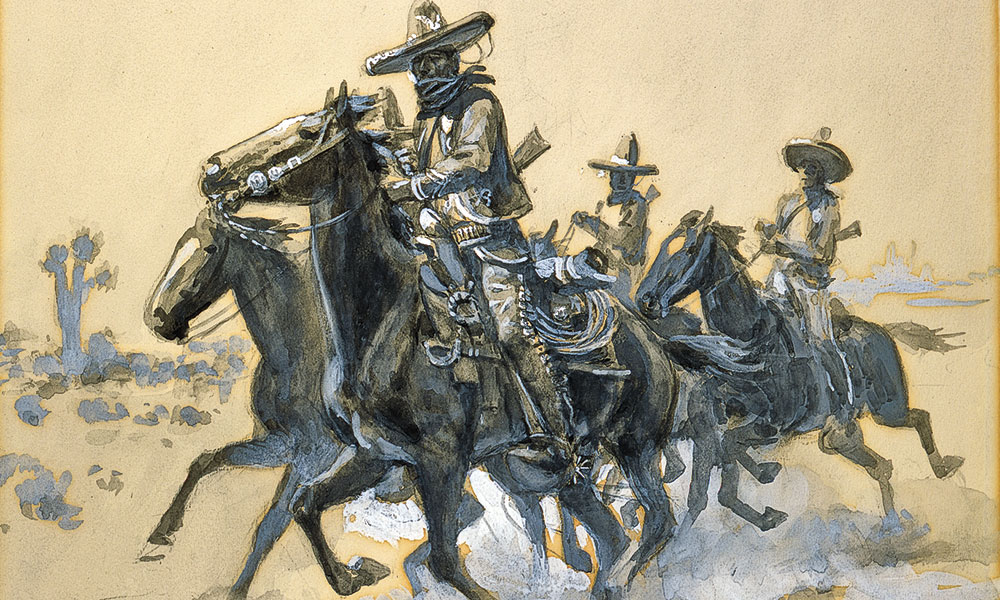

— Courtesy Stark Museum of Art, Purchase of the Nelda C. and H.J. Lutcher Stark Foundation, 2004, Orange, Texas, 31.2.3 —

Blame it on Joseph McCoy.

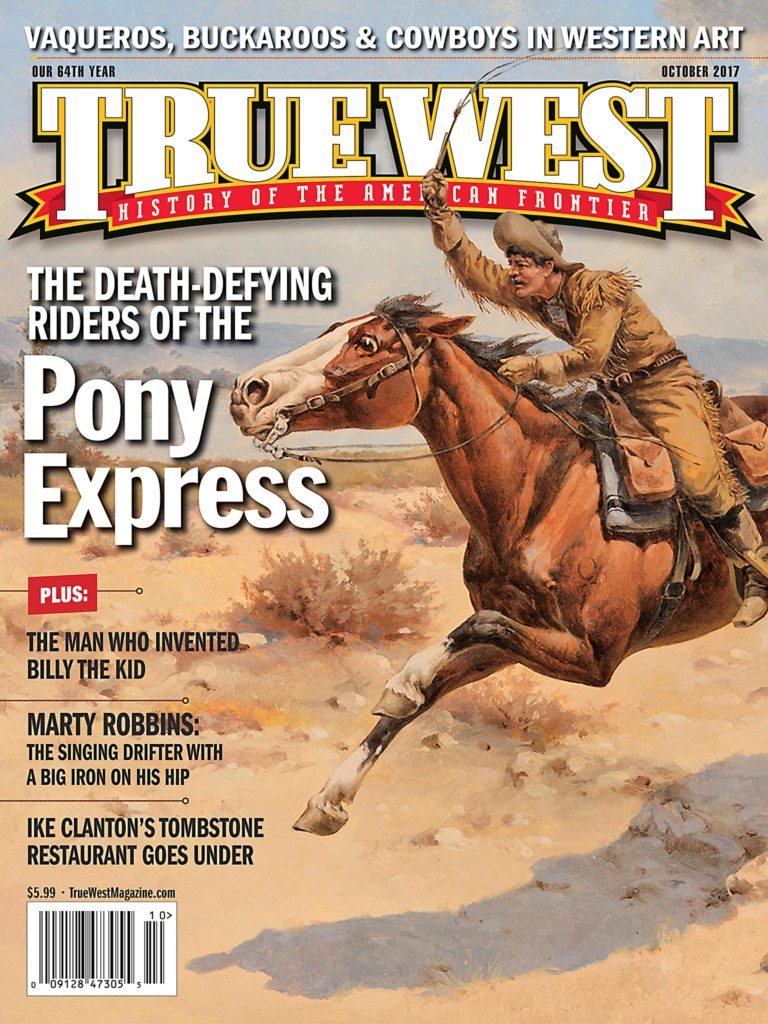

The entrepreneur turned Abilene, Kansas, into a cowtown, which made the Chisholm Trail synonymous with cowboys and the Wild West. Which led to cowboy, vaquero and buckaroo art—all vibrant today on the 150th anniversary of the Chisholm Trail.

Yet McCoy also wrote a book, Historic Sketches of the Cattle Trade of the West and Southwest, published in 1874, which played a part in art, too.

“There are not many images of drovers and drives from the early days of the Chisholm Trail,” says B. Byron Price, director of the University of Oklahoma’s Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West. “Some of the first illustrate McCoy’s Historic Sketches of the Cattle Trade.”

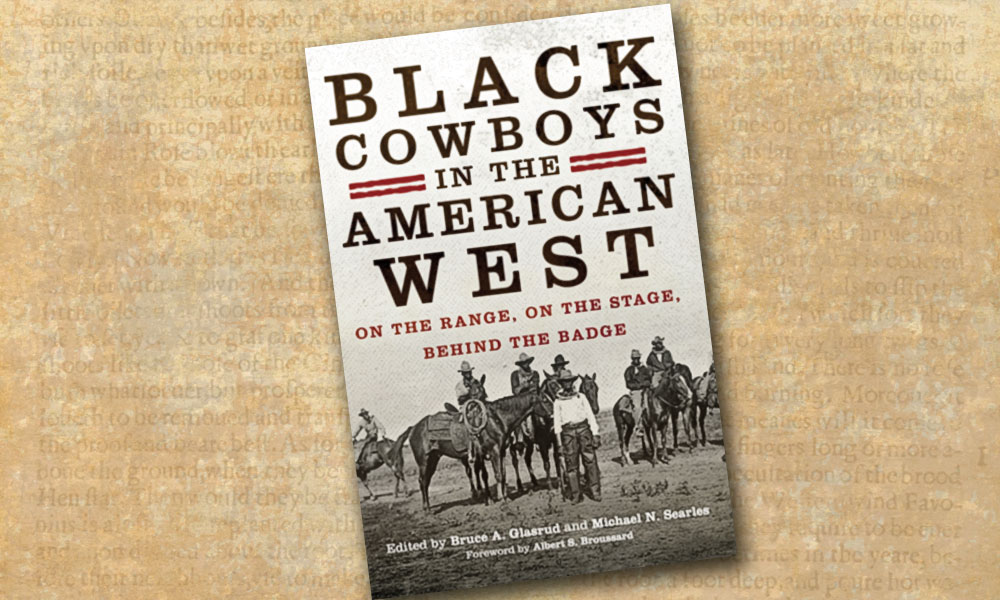

Sure, Missouri-born Charles M. Russell (1864-1926), among the greatest Western artists, was a Westerner and a Montana cowboy. But many Western artists—including New Yorker Frederic Remington (1861-1909)—were not Westerners, and few were cowboys. None that we know trailed cattle from Texas to Kansas between 1867 and 1886.

But all created memorable art.

— Courtesy Legacy Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona —

Rufus F. Zogbaum (1849-1925), W.A. Rogers (1854-1931), Charles Schreyvogel (1861-1912), Frank Tenney Johnson (1874-1939) and Maynard Dixon (1875-1946) followed Russell’s and Remington’s trails. Sculptors Walter Winans (1852-1920), Hermon A. MacNeil (1866-1947) and Solon Borglum (1868-1922) garnered international acclaim. As Western fiction became popular, illustrators Frank Schoonover (1877-1972), W.H.D. Koerner (1878-1938), Alan Tupper True (1881-1955), N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945), Harvey Dunn (1884-1952) and A.R. Mitchell (1889-1977), among others put their own touches on cowboy art.

“Many early Texas artists who were known for their Western scenes tried to capture a way of life that they saw was quickly dwindling,” says Mary E. Burke, director of the Sid Richardson Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, which is following its successful “Hide & Horn on the Chisholm Trail” exhibit with “Frederic Remington: Altered States.” “Like Charles Russell, they wanted to capture this way of existence before it was gone forever,” Burke says.

Take, for example, Harold D. Bugbee (1900-1963), who “fashioned himself as the South Plains version of Charles M. Russell,” Burke says. “He grew up on a ranch in the Texas Panhandle and developed his artistic skills through sketching the many facets of ranch life, which resulted in paintings of the American West later in his career.”

— Courtesy Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, 1961.201 —

Or Frank Reaugh (1860-1945): “Based in Dallas, Reaugh often traveled west with various cattle outfits, sketching and painting scenes of the remaining open range,” Burke says. “Later, Reaugh would take his students on annual sketching trips to West Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.”

Before there were Texas cowboys, of course, there were the vaqueros of Mexico.

“The only artist that specialized in Mexican and California vaqueros was Edward Borein [1872-1945], who spent a good bit of time in Mexico and made one sure enough drive in the early 1900s from William Randolph Hearst’s Bavicora Ranch into souther New Mexico,” Price of the Russell Center says.

Russell, who painted Vaqueros of Old California in 1923, also wrote about vaqueros, those “cow people” who “were generally strong on pretty, usin’ plenty of hoss jewelry, silver-mounted spurs, bits, an’ conchas…”

— Courtesy Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming, USA, Gift from Private Collection, 75.72 —

Vaquero was corrupted into Buckaroo, and buckaroos continue that tradition today, primarily in Nevada’s Great Basin. Buckaroo artists, like Carl F. Hammond of Burns, Oregon, preserve that image.

The West and Western art even fascinated Dwight D. Eisenhower, who grew up in Abilene and later collected works by cowboy artist Olaf Weighorst (1899-1988). The Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum and Boyhood Home’s exhibit “Chisholm Trail and the Cowtown that Raised a President” runs through May 2018.

Cowboys, vaqueros and buckaroos keep capturing the imagination of artists today—from traditional scenes by Jack Sorenson and Curtis Fort to contemporary cowboys by Tim Cox and Bruce Greene to contemporary art by Billy Schenck and Michael Swearngin.

— Courtesy Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, Museum purchase, 1955.164 —

Art museums on the Chisholm Trail haven’t forgotten their heritage, either.

“It’s an important part of the history of this area,” says Teresa Veazey, public relations manager of the Witchita Kansas Art Museum, about the museum’s “Heritage of the West” exhibit. “Museum patron M.C. Naftzger deemed Western art important enough to develop a collection at WAM that includes artists such as Russell and Remington.”

— Courtesy Schenck Southwest, Santa Fe, New Mexico —

Today’s artists and art lovers keep that history alive.

“The drama, uncertainty and excitement of the trail drives, and the struggles, friendships and conflicts of the people who traveled them, are authentic,” Burke says, “and they do continue to capture our imagination.”

Johnny D. Boggs has researched Chisholm Trail cattle drives often—including for his novels The Lonesome Chisholm Trail, Summer of the Star and Return to Red River—and has two fractured ribs to prove it.