Muskogee, Oklahoma’s early years as a frontier outpost were violent, dangerous and unpredictable.

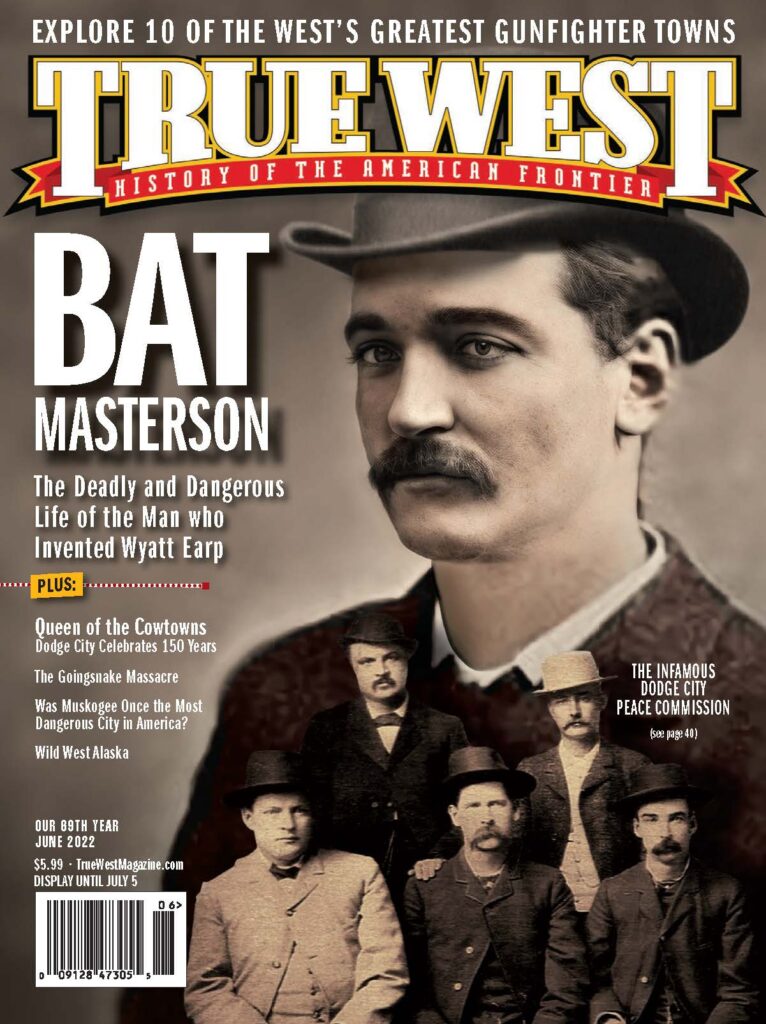

Welcome to Muskogee, the rip-roaring and most dangerous locale west of the Mississippi River. Over the years I have read about Deadwood, Dodge City, El Paso, Las Vegas, New Mexico Territory and Tombstone, Arizona Territory. These towns were wild for four or five years; Muskogee of the Indian Territory was wild for over 40 years. There were over 130 deputy U.S. marshals killed in the Indian and Oklahoma territories during the frontier era, and most were killed within a 50-mile radius of Muskogee. There were also commissioned United States Indian policemen killed in the line of duty in the same locale. Muskogee and the surrounding counties saw more murders of federal lawmen than anywhere else on the Western frontier.

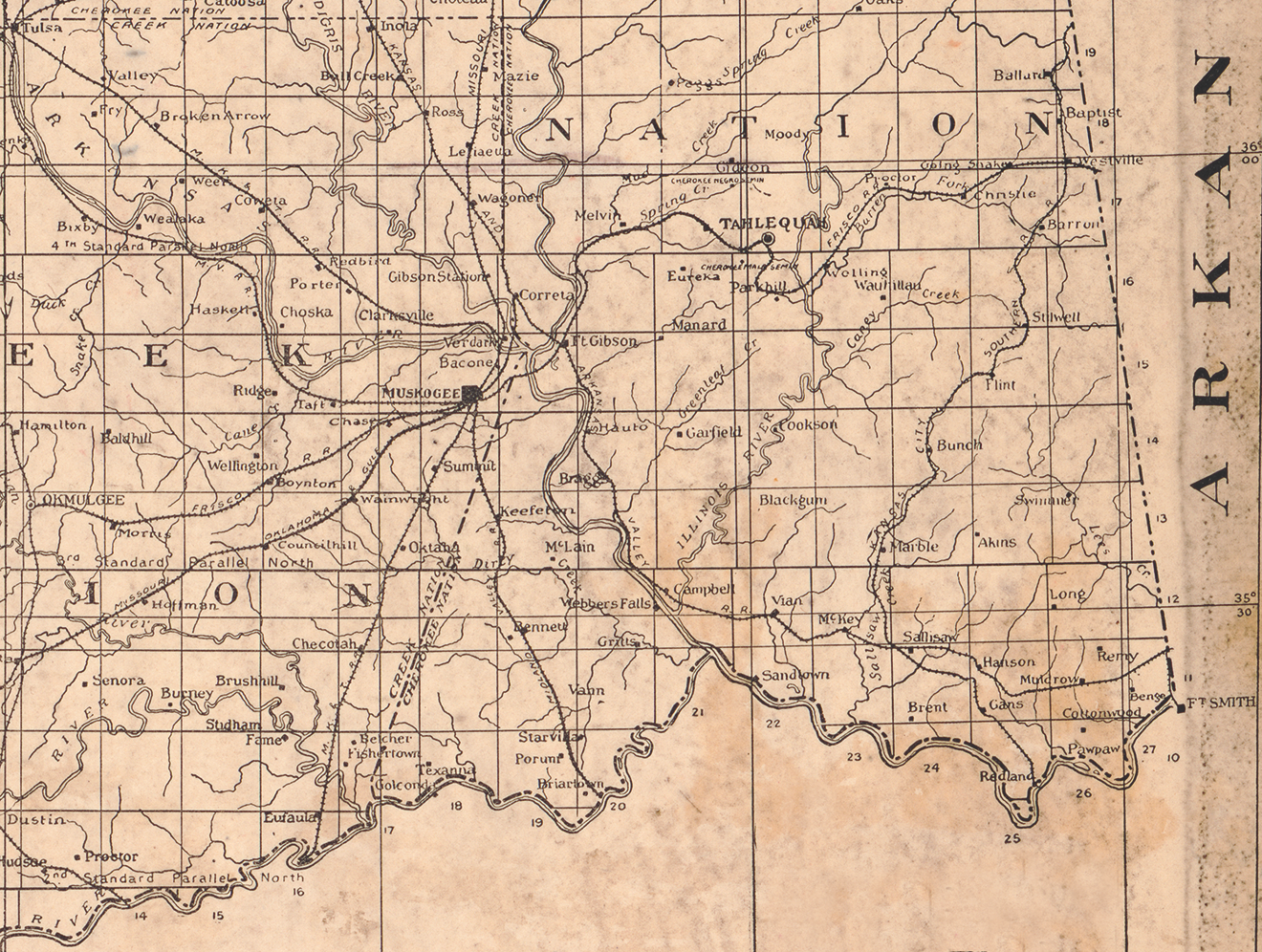

Muskogee was originally spelled Muscogee but was changed permanently as time went on. The town was situated near the locale known as “The Three Forks” of the Arkansas, Verdigris and Grand rivers, near the borders of the Cherokee and Creek Indian nations. The original inhabitants were principally former enslaved Blacks of the Cherokee and Creek nations who lived near the river bottoms. The town itself took shape in 1872 with the arrival of the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad, called “The Katy” by locals along the rail line. Muskogee was a terminus or end-of-rail town, as they were called.

A Wicked Little Town

In January 1873, Edward King, a writer for Scribner’s Magazine wrote an article on the frontier railroad. King interviewed George Reynolds, a Katy special agent in the Indian Territory. During the interview, Reynolds said: “Three men were shot about twenty feet from this same car in one night in Muskogee. Oh! This was a little hell, this was. The roughs took possession here in earnest…. There was no law here, and no means of getting any. As fast as the railroad moved on, the roughs pulled up stakes and moved with it…. It was next to impossible for a stranger to walk through one of these canvas towns without getting shot at. The graveyards were sometimes better populated than the towns next to them.”

Writer King noted with curiosity Muskogee’s cemetery, where 11 men were buried with their boots on. “Each grave,” he wrote, “is a monument to murder.”

One of the local outlaws present in Muskogee in 1872 was a mixed-blood Cherokee named Brad Collins. Collins was nearly white in appearance, a smuggler of whiskey, a desperado and a dead shot. It was said that he could throw a pistol in the air, causing it to make half a dozen turns, catch it as it fell and strike an apple at 30 paces. It was reported that other “shootists” in the Indian Territory were in awe of him.

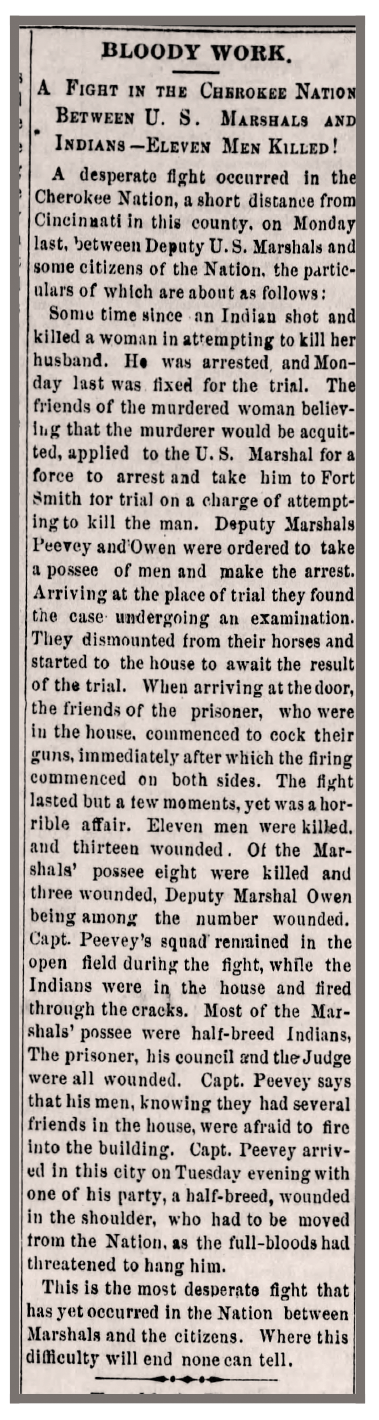

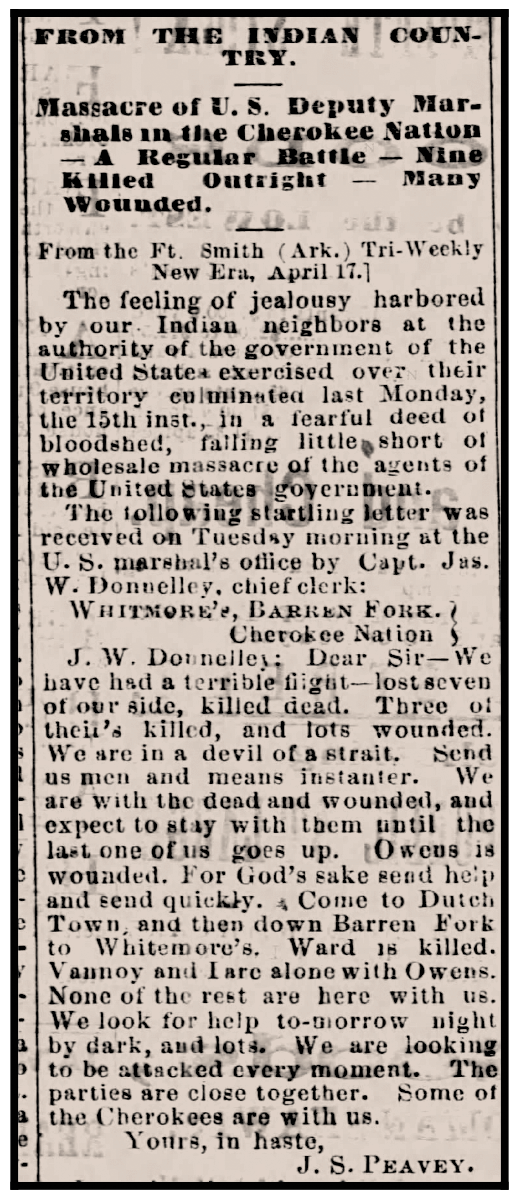

In the spring of 1872, the athletic young Collins was under bond to appear at the May term of the federal court in Fort Smith, Arkansas, for shooting at a deputy United States marshal with intent to kill. Many excused him for a previous incident in which he had killed a deputy U.S. marshal because it was a private quarrel. Collins’s gang included a dozen or more mix-blooded Cherokees.

At that time in the Indian Territory, crimes committed by Indians against Indian citizens were heard in the Cherokee or Creek Indian judicial courts. If a White man committed a crime or was the victim of a crime, the case was heard at the federal court at Fort Smith, which had jurisdiction over western Arkansas and all the Indian Territory. The court’s jurisdiction covered 75,000 square miles and was the largest federal court in the U.S. at the time.

As a frontier town and a railroad terminus town, Muskogee was unique. Other terminuses quickly settled down to become quiet, respectable communities, or faded away altogether. Muskogee alone remained rip-roaring and lawless for 20 years or more.

When the Katy Railroad reached The Three Forks in the fall of 1871, the United States agents for the Five Civilized Tribes were headquartered individually with their tribes. The Cherokee agent had his offices in Tahlequah; the Choctaw and Chickasaw agent was located at Boggy Depot; the Creek agent was located near Muskogee; and the Seminole agent was at Wewoka. On July 1, 1874, the government ordered the consolidation of these agencies, and thereafter the United States Agency for the Five Civilized Tribes was known as the Union Agency.

After two years of negotiations, the consolidated agency was finally located at Muskogee, and on or about January 1, 1876, the agent for the Five Civilized Tribes moved into a brand-new Union Agency building. The choice of Muskogee as headquarters for the land-wealthy Indian tribes was probably the decisive factor in Muskogee’s survival.

The town of Muskogee was in the Muskogee District of the Creek Nation. Most of the Creek Lighthorse policemen for the Muskogee District were African Americans. The Blacks were former slaves or descended from former slaves of the Creek Indians, and they were known as Creek Freedmen or Indian Freedmen. There was bad blood between the Creek Freedmen and the Cherokee mixed-bloods. In Muskogee, on Christmas Day 1878, serious trouble broke out when some Black Creek Lighthorsemen disarmed John and Dick Vann, two young Cherokees from a prominent family. A lawless Texan passing through town attempted to put the Black officers in their place. He led the Cherokees in the gunfight that eventually cost the life of one of the Lighthorsemen and wounded three other Black officers.

In August 1879 another bloody gunfight took place in Muskogee: John Vann was killed and the Creek Lighthorse captain was wounded. Creek Chief Coachman decided to place a Lighthorse officer on guard in Muskogee proper. He ordered Richard Berryhill, the reliable and efficient captain of the Eufaula District, to undertake the work. But Berryhill protested that the assignment “Seems to me to be a severe one. If the town of Muscogee was really an Indian town I would not wait a moment, but as it is there are but few Indians there. I am more than willing to serve my people but the way things are I don’t see how I am to risk my life for non-citizens.”

Muskogee was principally a “cow town” during its early years. The town was part of the Shawnee Cattle Trail which went along the route that had been known as the Texas Road. Muskogee also had Katy Railroad cattle pens for shipping, which meant that cattle and cattlemen were big business in the community. Cattle theft was always a problem in the frontier Muskogee area for lawmen, both Indian and federal.

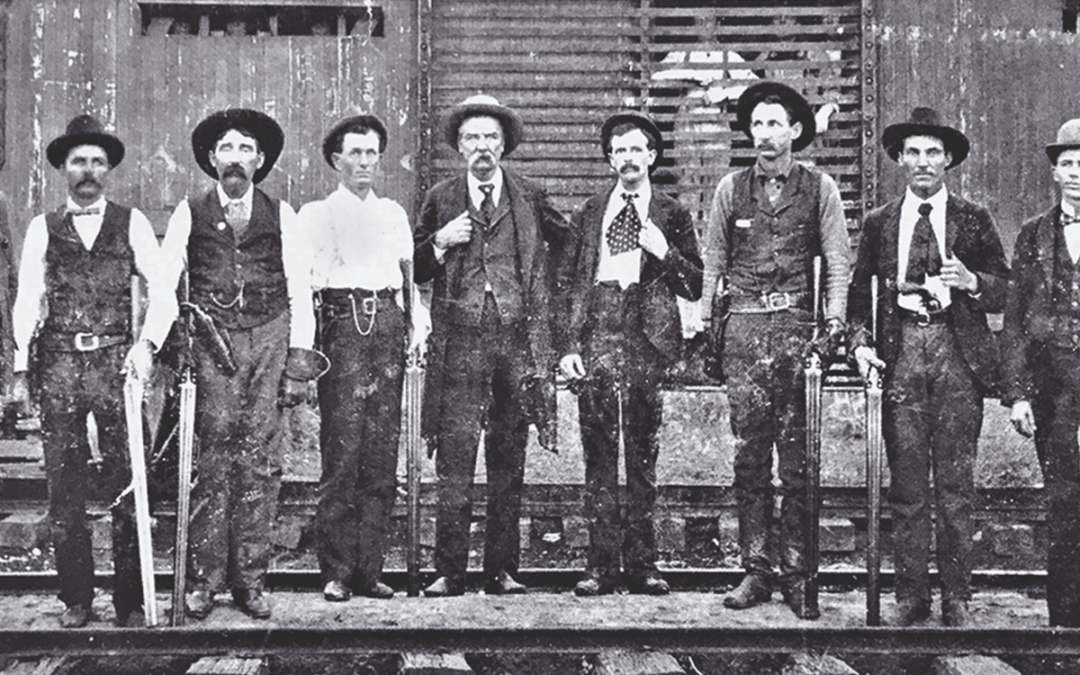

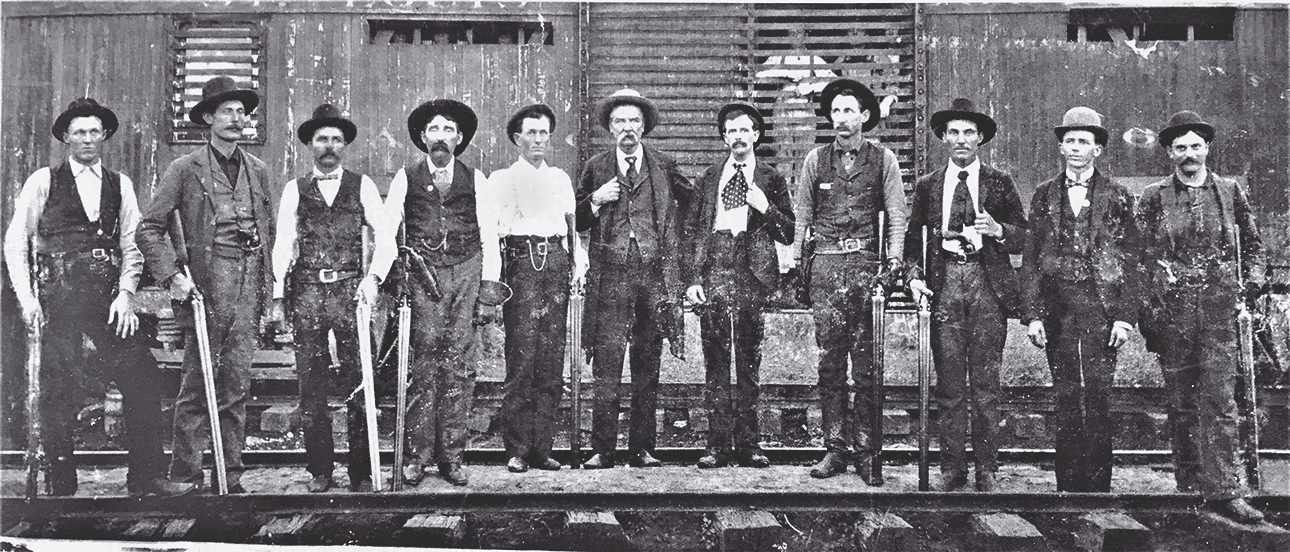

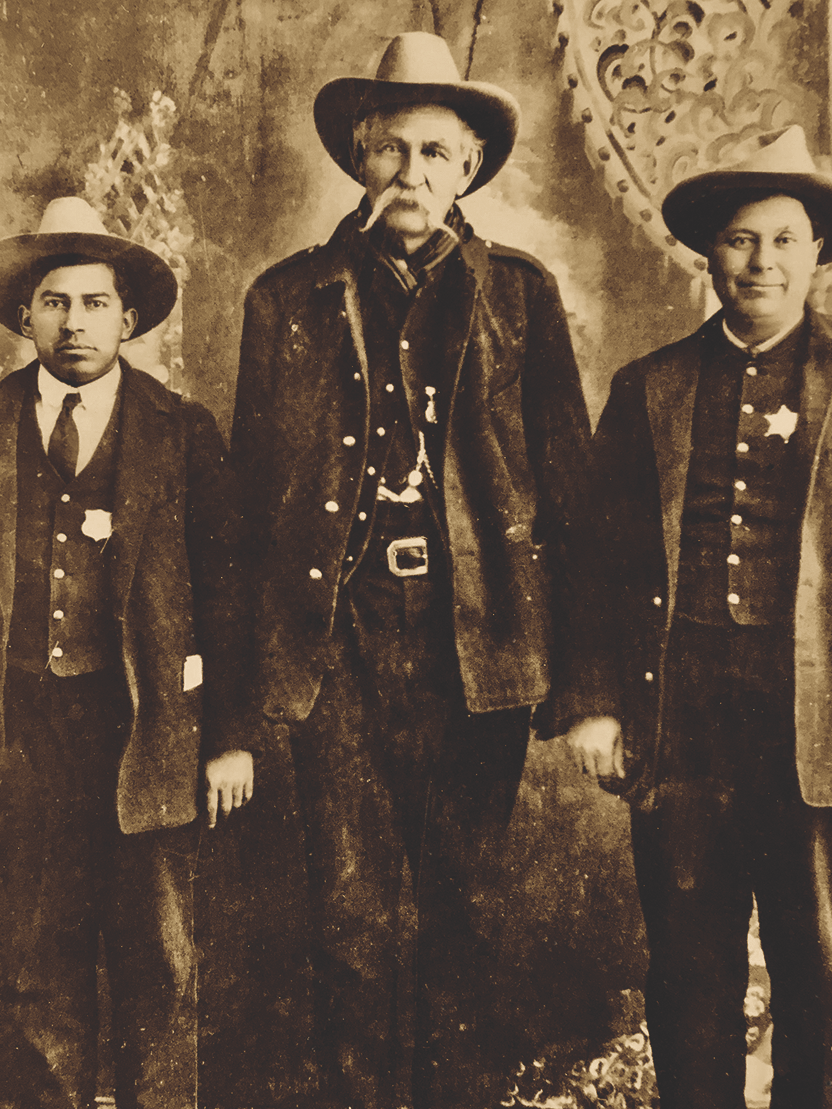

In February of 1880, Col. John Q. Tufts, United States agent for the Union Agency at Muskogee, I.T., organized a unit of Indian police to operate throughout the Five Civilized Nations. Agent Tuft’s organization of Indian policemen consisted of 30 members, one-third of whom were Cherokees. Their duties were to preserve order, arrest thieves and violators of U.S. law, suppress the whiskey traffic and execute the orders of the Indian agent. They were stationed at different points within the jurisdiction of the Union Agency and were on duty wherever found.

Deadly Streets of Muskogee

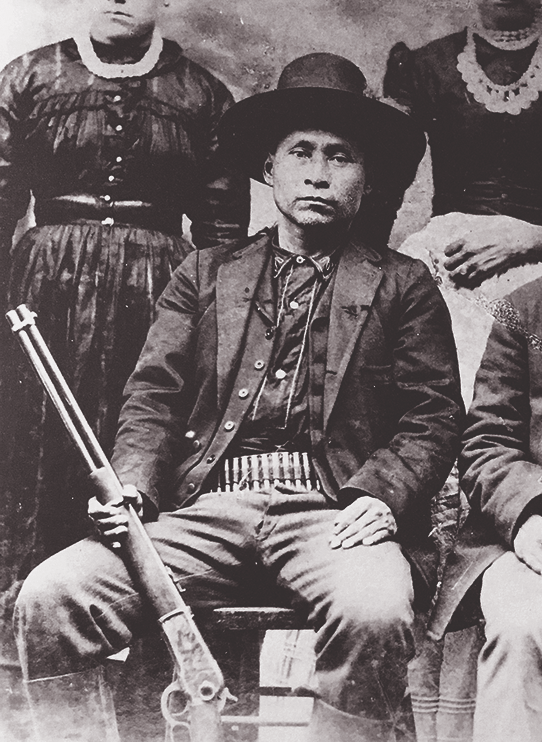

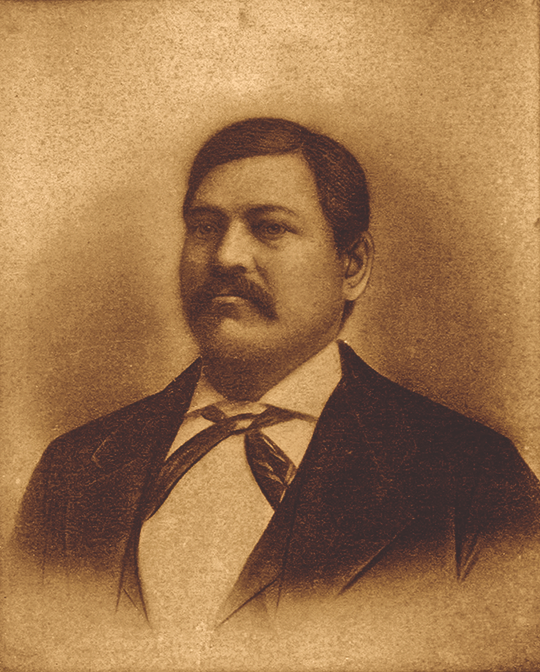

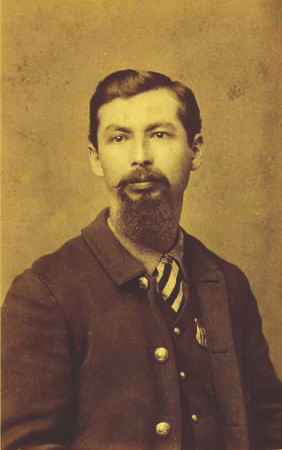

The first chief of the Union Agency police, and most famous Indian policeman in the history of the Indian Territory, was Capt. Sam Sixkiller. He was assisted by his brother Henry Sixkiller on the U.S.I.P. as it was known in the territory. Muskogee itself was the foremost responsibility of Captain Sixkiller since the Union Agency was headquartered there. Sixkiller also held a commission as a deputy U.S. marshal and a special agent for the Missouri Pacific Railroad, which had recently built a line through the territory. Sixkiller’s problem centered around bootleggers, cattle thieves, murderers, rapists, timber thieves, White intruders, train robbers, card sharks and prostitutes following the railroad towns.

Sixkiller was outstanding in his law enforcement work but was killed while off duty in Muskogee on Christmas Eve of 1886. Two Cherokee desperados caught the unarmed Sixkiller on the streets of Muskogee and filled him with pistol and shotgun fire until he fell dead. Sixkiller’s successor as captain of the Union Agency police, William Fields, lasted only three months before he was shot to death.

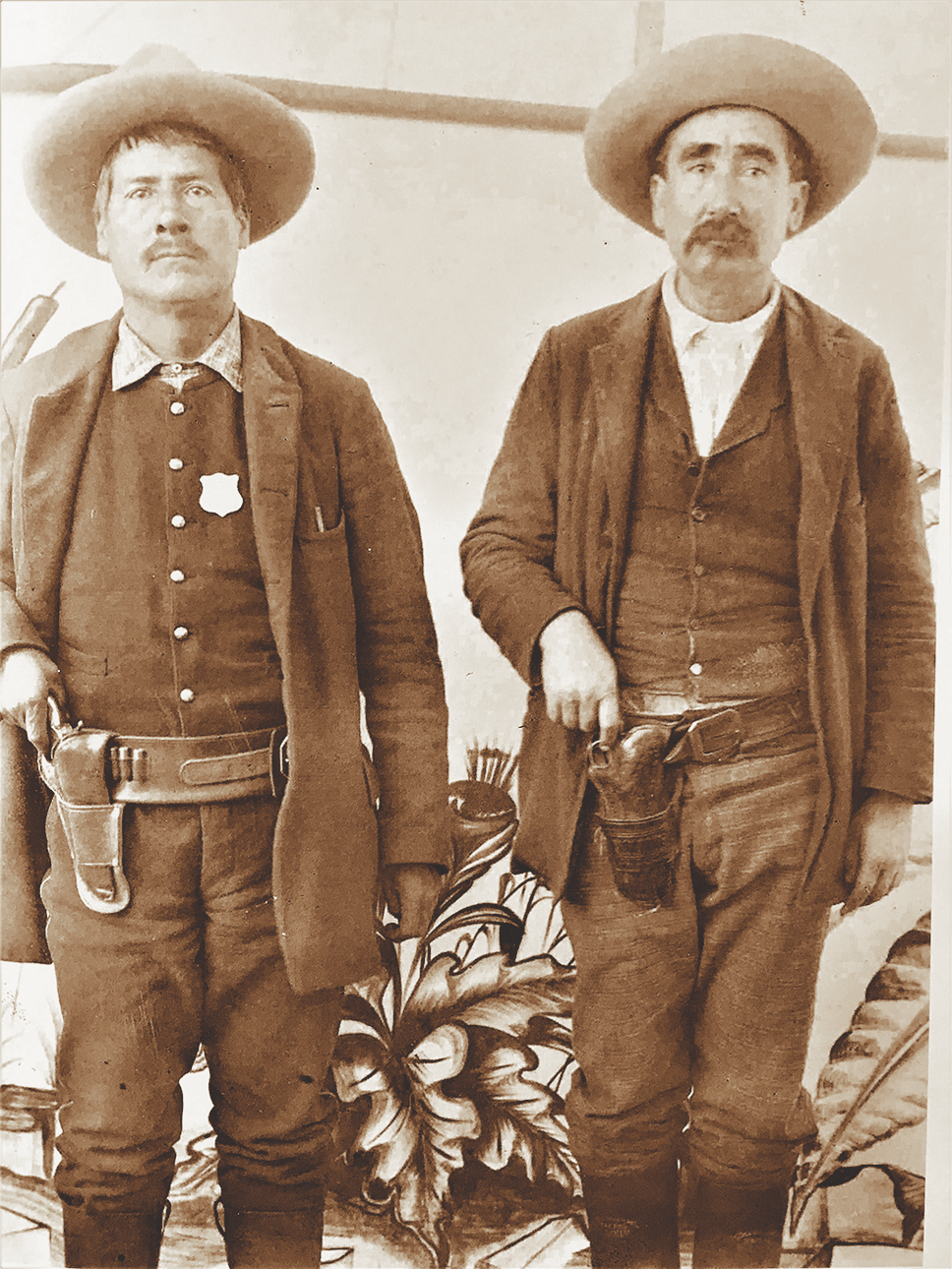

In 1888, Bud Kell, a Cherokee who was a well-known and noted deputy U.S. marshal for the Fort Smith federal court and a sergeant in the United States Indian Police at Union Agency, was made Muskogee’s first city marshal. Kell was hired by the business community of Muskogee.

In 1889 the Fort Smith court’s jurisdictional land area was broken up. Muskogee was selected as the first court in Indian Territory. They only had jurisdiction over minor crimes; major crimes were referred to Fort Smith. Most of the law enforcement for the Muskogee area was done by deputy U.S. marshals assigned to the Fort Smith federal court. In July of 1893, a deputy U.S. marshal named Sherman Russell from the Fort Smith court was killed at Muskogee while trying to deliver an arrest warrant. The fugitive was never apprehended.

By 1897 the federal court at Muskogee had full coverage for the Northern Federal District for Indian Territory. The U.S. marshal for the court was Leo E. Bennett. One of the deputies assigned to the court that year was the legendary Black Fort Smith Deputy U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves, who earlier had worked for the federal court at Paris, Texas. The town of Muskogee was incorporated in March of 1898, and at the same time its first municipal police department was formed.

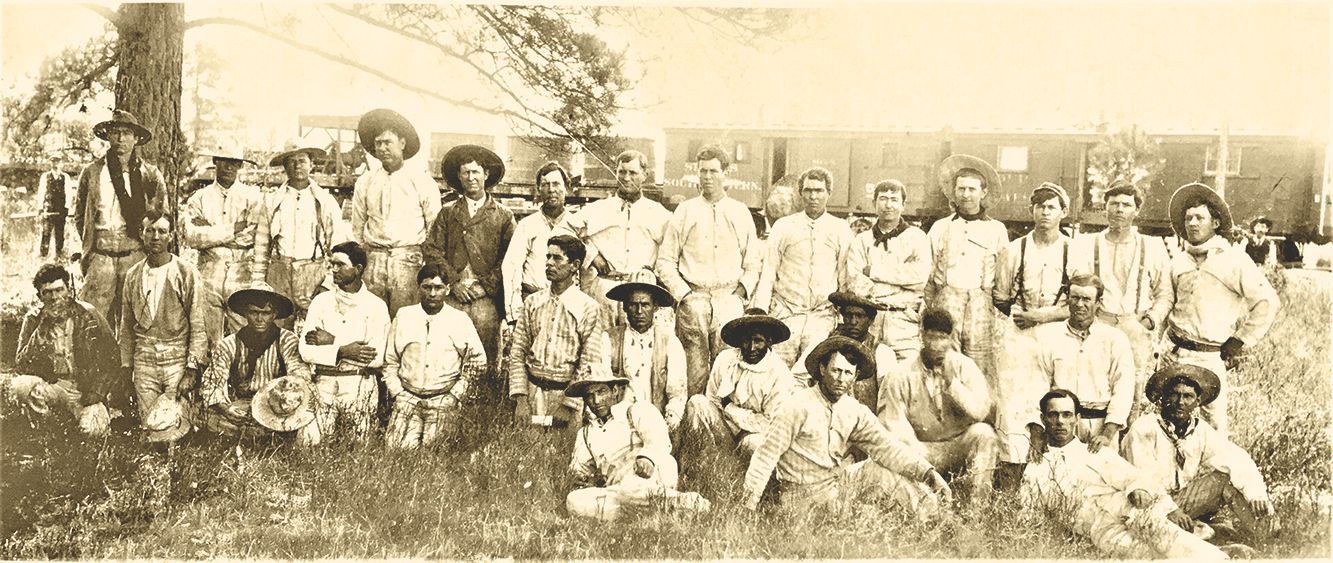

In 1902, the two deputy U.S. marshals assigned to Muskogee were Bass Reeves and a White man named David Adams. For the most part Adams served as Reeves’s posse. Although Muskogee had a municipal police department because it was part of the Indian Territory, most of the work fell on the U.S. marshals’ office for criminal activity in and around Muskogee. In May 1902, Reeves and Adams went to the nearby town of Braggs in the Cherokee Nation and arrested 24 men for being involved in a race war. They arrested 15 White men and nine Black men without any resistance and brought the prisoners to the federal jail in Muskogee.

The biggest gunfight in Muskogee took place the same year as statehood in 1907. A group of Black anarchists called the United Socialist Club led by preacher William Wright took over a large two-story house in Muskogee and said they didn’t have to pay rent. On March 26, 1907, two city policemen, John Colfield and Guy Fisher, were dispatched to serve eviction warrants. The policemen were attacked; Fisher was wounded in the shoulder and Colfield was shot in the chest. Chief Deputy U.S. Marshal Bud Ledbetter, along with a large group of lawmen, both city and federal, arrived at the house. During the intense gunfight Ledbetter was identified as killing two of the anarchists, and Bass Reeves killed one and wounded another. Paul Smith, a Black city officer, killed one of the desperadoes and in doing so saved Bud Ledbetter’s life during the gunfight. Another Black city officer involved was R.C. Cotton. Of the socialist group in the gunfight, five were killed and seven were arrested.

As a frontier town Muskogee was well integrated with no segregated housing between Blacks, Whites and Indians. Everyone shopped downtown at stores and businesses owned by various ethnic groups. There were two Black business districts in Muskogee that were popular with all the residents of the town. Muskogee became the federal headquarters for the Dawes Commission which broke up Indian lands held in common and parceled out allotments to Indians and Indian Freedmen before Oklahoma statehood in November of 1907.

Muskogee was a wild frontier town for many years with legendary lawmen like Bass Reeves, Bud Ledbetter, Bud Kell and Sam Sixkiller to keep the peace. We have heard about Tombstone, Deadwood, Dodge City and El Paso, but we have to add Muskogee of the Indian Territory to the list of Western frontier towns of note. Muskogee was the cow town, end-of-rail town, wild West town that was too tough to die.

Art T. Burton, a retired college history professor, is the biographer of lawman Bass Reeves and outlaw Cherokee Bill. Burton’s research has shed light on frontier individuals who have received little press. He has appeared in many television documentaries on the Western frontier and the Old West.

Editor’s Note: True West’s Executive Editor Bob Boze Bell will be the keynote speaker for the 2022 Bass Reeves Western History Conference in Muskogee, Oklahoma, July 21, 22 and 23.