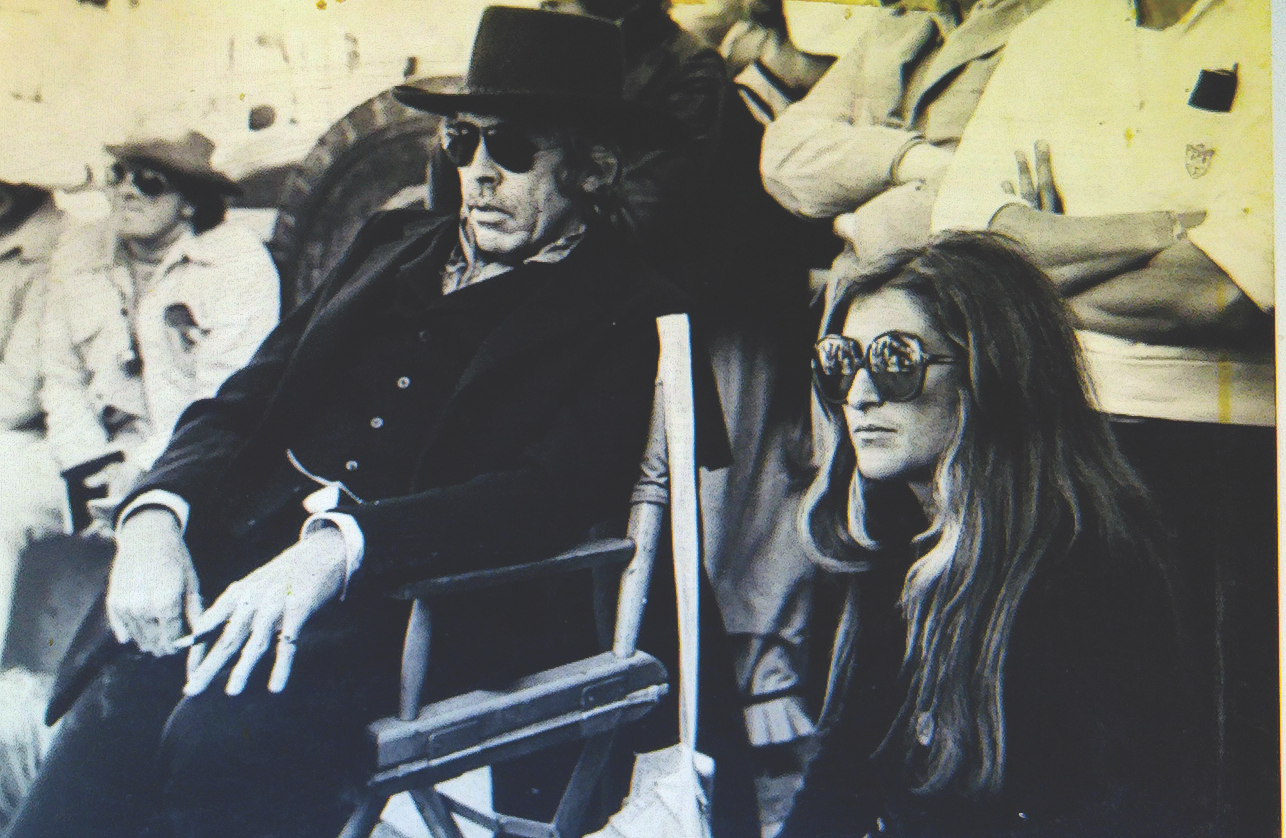

Sam Peckinpah’s Girl Friday, and Saturday, and Sunday, and…

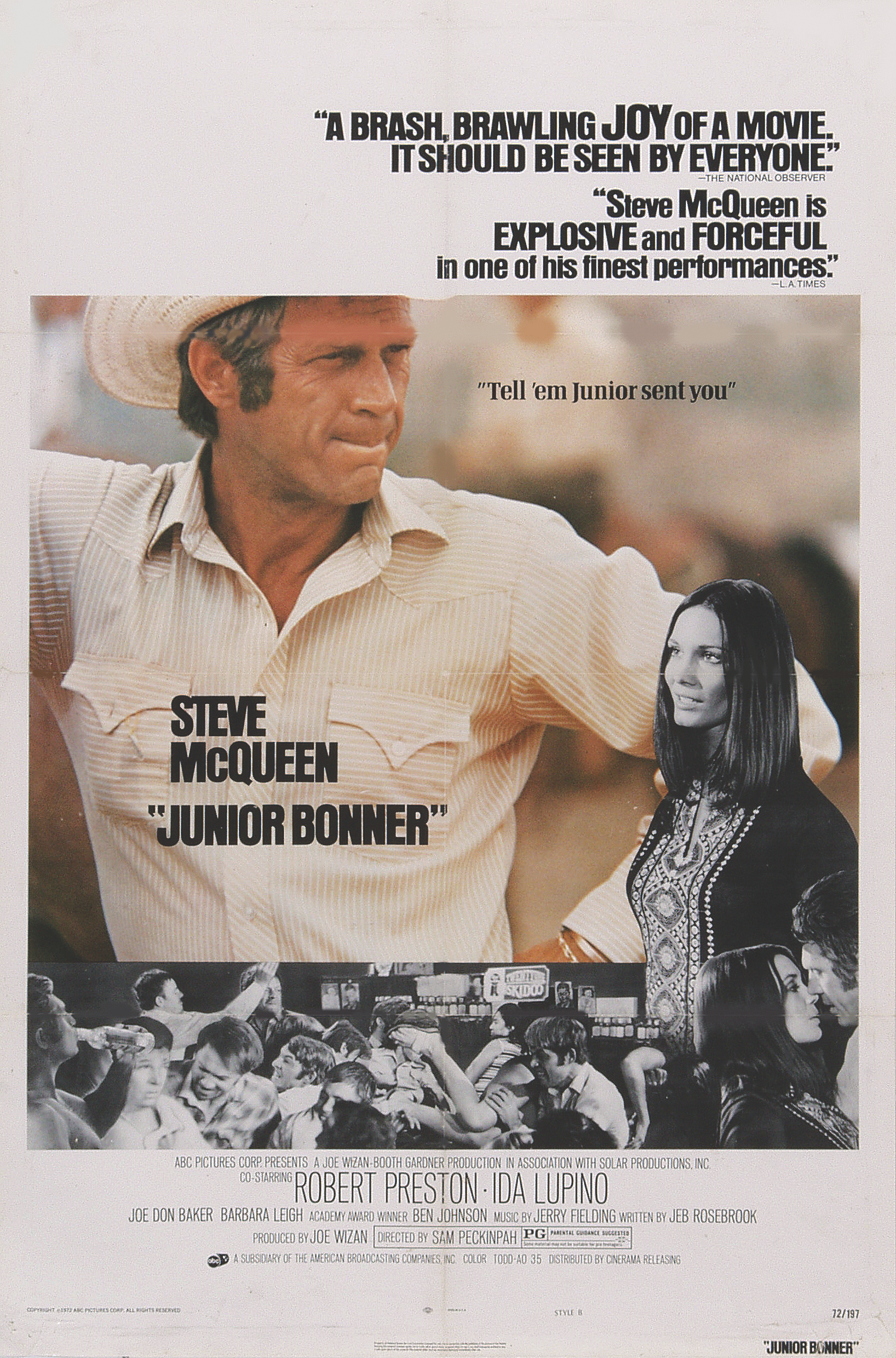

Courtesy ABC Pictures

Film is the most collaborative of arts: no one makes a movie alone. So, how important might an assistant be to an auteur like Sam Peckinpah? A woman who was constantly by his side for eight movies in seven years? According to Mark Kermode, film critic for the BBC, “It wouldn’t be completely fanciful to say she was the co-director. She was allowing the director to direct.”

Sam made Straw Dogs, Junior Bonner, The Getaway, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, The Killer Elite, Cross of Iron, and began Convoy with Katherine “Katy” Haber, MBE, by his side, and as his “demons”—alcohol and drugs and paranoia—became more pronounced, her job of holding things together became ever more demanding.

It was certainly an unexpected life for the daughter of Czechoslovakian Jews who had fled to England when Hitler’s troops marched into Prague in 1939. It was always planned that Katy would follow her dermatologist father into medicine. But when his depression led him to suicide, she says, “I decided that I would not have my mother pay an inordinate amount of money to get me through university. I decided to go into the film business.”

In the late ’60s she’d worked as assistant producer to Ronald J. Kahn on theater and film productions, including Prudence and the Pill and Girly. Peckinpah was in England in 1971 to make Straw Dogs. Producer Sir James Swann called her. “‘Sam’s been through three or four different assistants, and all of them wanted to have lunch breaks and have their hair done. They couldn’t take his odd curriculum.’ So I went to see him, and he said, ‘Can you type?’ I said, yes. He threw me the script, and I started typing.” Of course, it was the rape scene. “Nothing prepared me for working with Sam Peckinpah—nothing.”

She began on Straw Dogs as a secretary, and by the end of the shoot, she was dialogue director, and so much more. That wasn’t the only way their relationship changed. “There was no romanticism about it; it wasn’t idyllic. But if romance means intimately involved, yes.” And then, the film was in the can, and it was over. “He said, ‘Thank you so much for everything that you did. Next time I come to England, we will work together.’” Then he was rushing off to Prescott, Arizona, to direct leading man Steve McQueen in the rodeo film Junior Bonner. They had to shoot key scenes during the actual World’s Oldest Rodeo and Frontier Days Parade in June and July 1971. “Two days after he left, I got a call, saying, ‘Get your fucking ass over here! We’ve got another movie to make! I can’t do it without you.’”

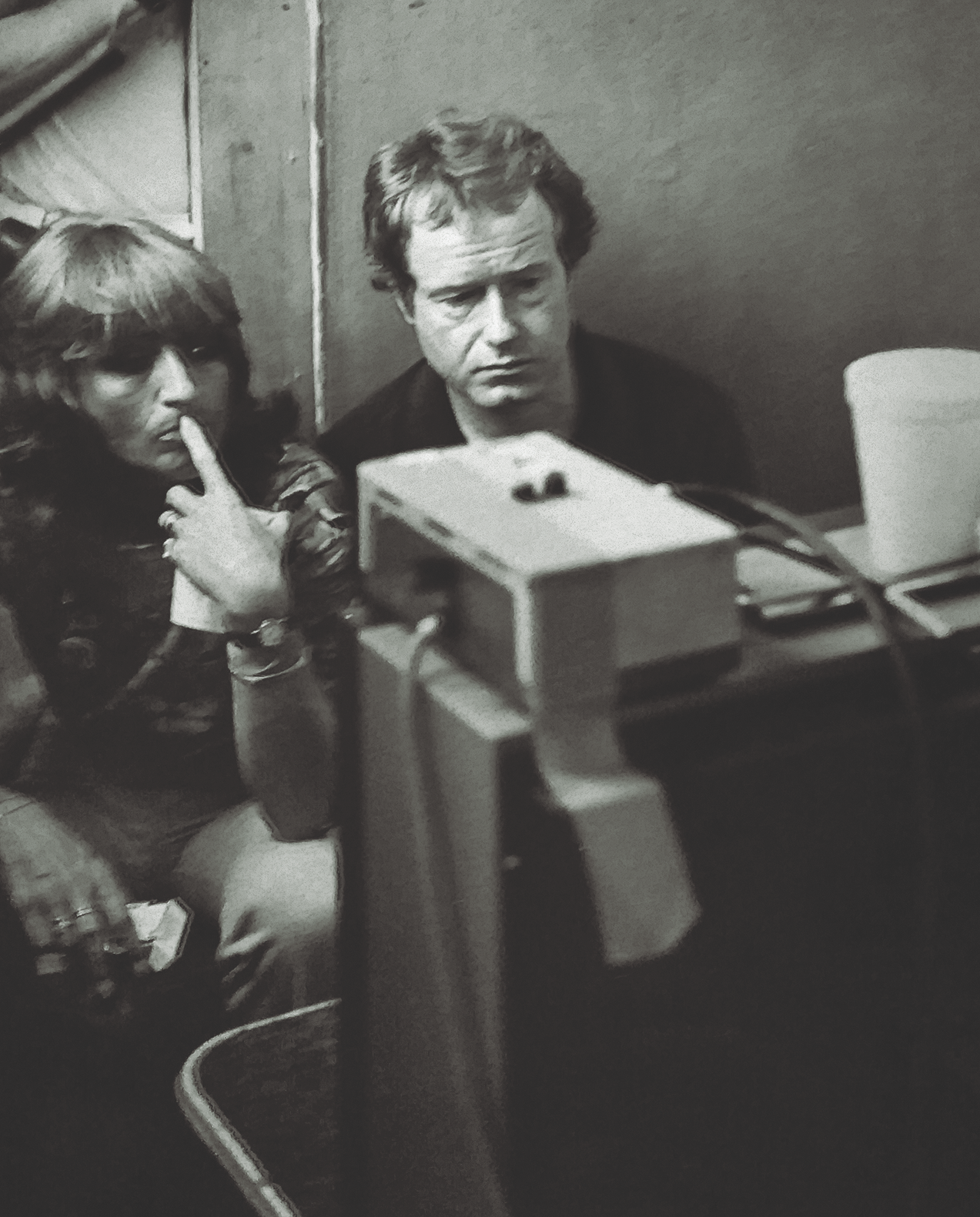

“Wherever Sam went, I was next to him, earphones on, script in front of me. Sam wasn’t concentrating on the actual prose of the film. I was able to tell him when they missed a line. He was not one for ad-libbing.”

She would run interference to protect the crew. “Sam would work all day, work all night, and then sleep at funny times. And if he had a thought, he would say, ‘Call the crew!’ And I would say, ‘I can’t find them,’ so that they could get a good night’s sleep.”

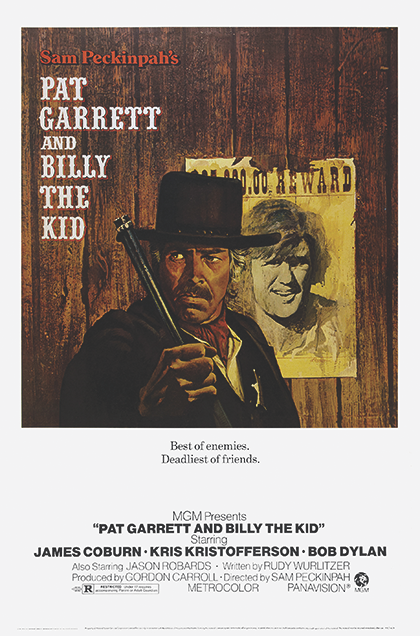

Toward the end of the shooting of The Getaway (1972) in El Paso, Texas, Sam crossed the border into Juarez and got married to his girlfriend Joie, so Katy was summarily fired and she returned home. She was immediately hired to work with Sam Fuller. When that project collapsed, as did Peckinpah’s marriage, he called Katy back, this time to Durango, Mexico, where he was two weeks into production on Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.

Often, she was protecting Sam from his producers. While he was editing Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), “[Producer] Jim Aubrey was cutting it in another editing room, taking out all the lyrical, prophetic and emotional sides to it. He just wanted it to be a bam-bam-thank-you-ma’am action film. When Sam finished editing, I would hide the film in the fridge.” Decades later, when they decided to release the director’s cut, Katy was able to provide it.

Sadly, when Peckinpah made the transition from liquor to cocaine, his paranoia increased to an intolerable degree. “He was very, very emphatic about knowing where I was at every second of the day, down to even bugging my room on Convoy.” That was the end: she quit. They never spoke again.

Katy went on to a long career in cinema in Hollywood, including as a producer of the sci-fi classic Blade Runner. Her dedication and service to underprivileged and underserved communities in Los Angeles, including the creation of the Compton Cricket team in 1995, was recognized by H.M. Queen Elizabeth II, who awarded Katy the MBE in 2012. She also helped start and served on the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, Los Angeles, for 23 years.

And she still has a couple of film projects in the works. She’s planning a miniseries about her family and the Holocaust. And there’s a novel she wants to film. “It’s called My Pardner. It’s Max Evans’s coming-of-age story about a kid who goes cross-country with a cattle rustler. I made a promise that I would get that movie made. Hopefully I can fulfill that promise.”

Sam Peckinpah died over 35 years ago. “He loved me, but loved to hate me, and hated to love me. I loved him and hated it. It was one of the most compatible-incompatible relationships, but it lasted seven years and eight films. So something must have worked.”

BLU‑RAY REVIEW

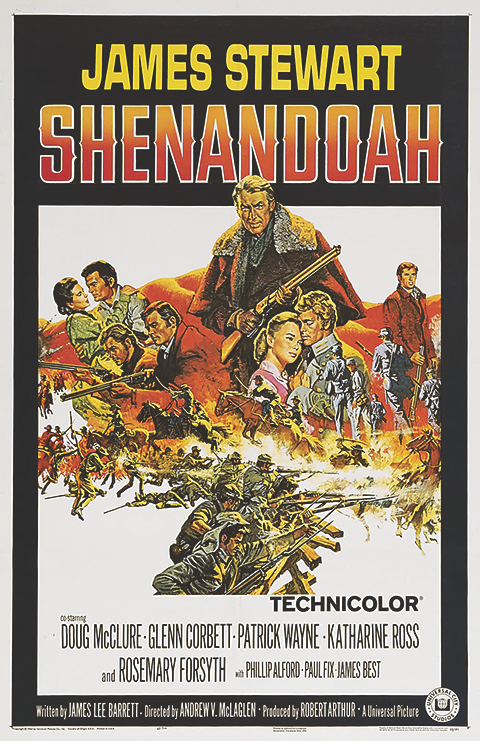

Shenandoah

(KINO LORBER—Blu-Ray $24.95) In June 1965, 11 months into the Vietnam War, former Army Air Corps Col. James Stewart starred in Shenandoah as a father determined to keep his seven sons out of the Civil War. The least-strident of the antiwar tragedy-Westerns, it was written by James Lee Barrett and directed by Andrew McLaglen with enough humanity and humor to make the story-cheats forgivable. A fine showcase for Doug McClure, Glenn Corbett and Patrick Wayne, it introduces Katharine Ross and Rosemary Forsyth. It’s among cinematographer William Clothier’s finest work. In 1966, his stepson, Marine Corps 2nd Lt. Ron McLean, having died in Vietnam, Air Force reservist Stewart, during his active duty, flew a bombing run against Vietcong targets.

Henry C. Parke, Western Films Editor for True West, is a screenwriter, and blogs at HenrysWesternRoundup.blogspot.com. His book of interviews, Indians and Cowboys, will be published later this year.