The tragedy at Goingsnake left 11 men dead—and a lot of questions.

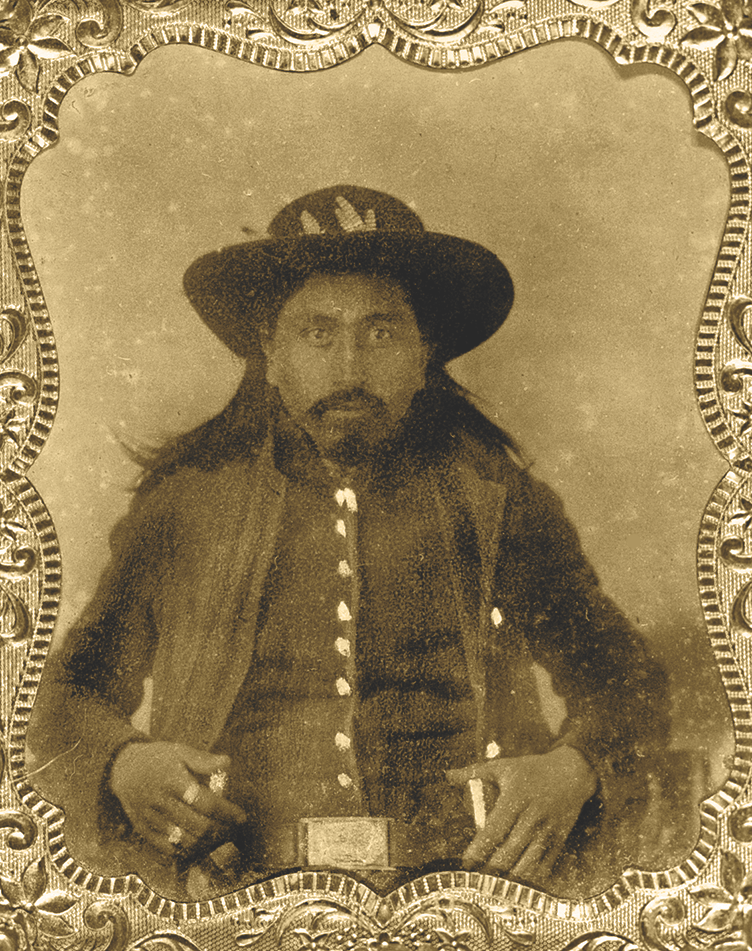

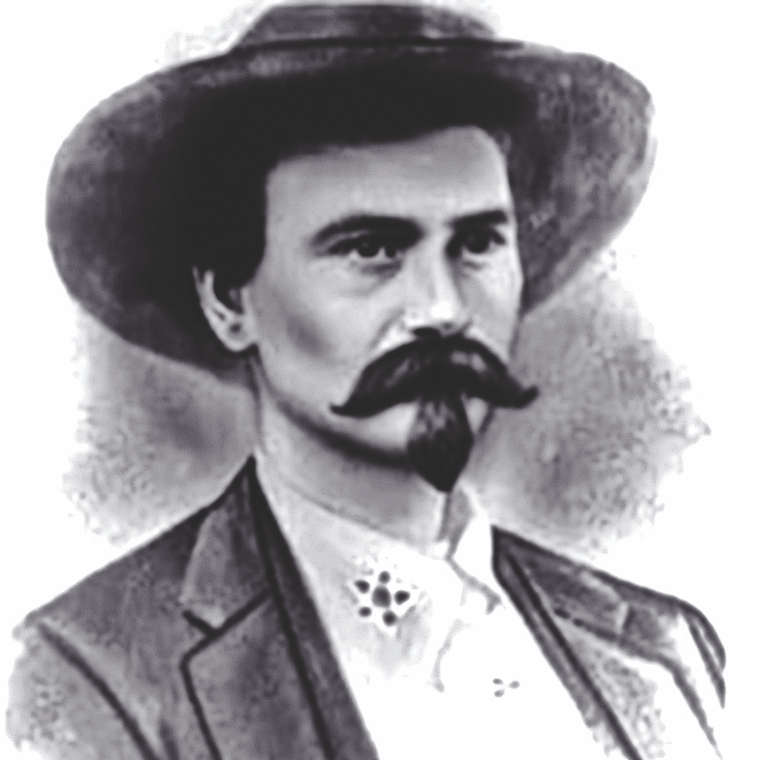

Ezekiel Proctor was a Cherokee and proud of it.

“Zeke” had walked the Trail of Tears from Georgia to the Indian Territory when he was a seven-year-old boy in 1838. He clung to the Cherokee language, culture and customs. He dealt with White folks, but he didn’t have much use for them.

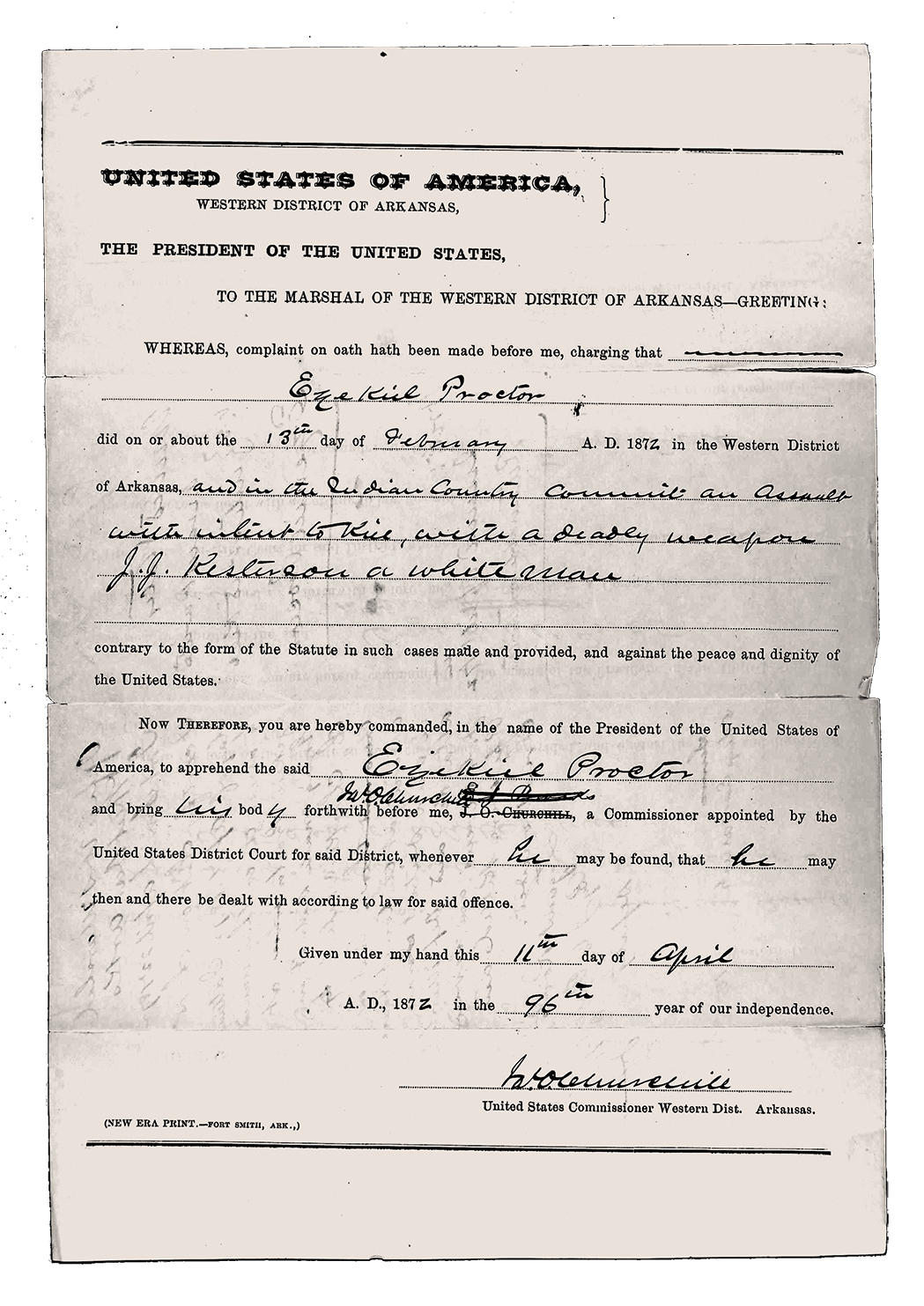

In 1872, the prosperous farmer and local lawman had a beef with one specific White man: his former brother-in-law, Jim Kesterson. Stories circulated of bad blood between them, a situation made worse when Kesterson abandoned Proctor’s sister and kids for another woman.

Proctor confronted Kesterson at the Hildebrand Mill, just west of Siloam Springs, Arkansas. He pulled a gun and opened up, but Kesterson’s new woman, Polly Beck, got in the way and was killed.

The shooting would bring Proctor into another confrontation: with the U.S. Marshals Service.

A Shocking Statistic

Formed in 1789 to enforce federal law, the U.S. Marshals Service suffered its first casualty five years later.

Between then and 1872, 11 other officers would die in the line of duty.

But the Indian Territory was bad ground for the U.S. marshals. Officially, between 1872 and Oklahoma statehood in 1907, a shocking 93 officers were killed there. Shocking because, to date, the U.S. Marshals Service has lost a total of 287 officers nationwide, meaning that nearly one-third of those killed lost their lives in the Indian Territory. The statistic is unmatched by any other place or any other period for line-of-duty deaths in American history.

The reasons for the disparity in the Indian Territory vary. Too few officers (200 or fewer) to patrol too large an area (more than 70,000 square miles). Many Indians didn’t think highly of the authorities representing the White government. And hard cases of all races found the region fertile ground for illegal enterprises, which fostered an ongoing struggle to control land and power.

Serving as a deputy U.S. marshal in the Indian Territory proved to be a tough and dangerous job, as well as a thankless one. The pay was miserable; based on fees and expenses, a deputy could expect to make between $400 and $800 a year. The pay often arrived late, sometimes months after it was due. Many of the deputy U.S. marshals took on second jobs, in local law enforcement, with the Indian police or as railroad detectives. More than a few padded their expense and travel reports to get extra money. Some, including Bob, Grat and Emmett Dalton, turned to crime, either on the side or full-time.

Why would anybody take on such a job? U.S. Marshals Service historian David Turk says some men didn’t want to be farmers or cowboys or merchants. “It was a job for the adventurous,” he says.

But too often, the adventure turned tragic. That’s what happened with Proctor and the Tragedy at Goingsnake.

Who Decides if Proctor Dies?

A lot of folks wanted to make Proctor pay after he killed Polly. Her kinfolk wanted Proctor dead—in spite of the fact that he was related to the Becks. The Cherokees wanted to try him since Polly had been a member of the tribe. The U.S., pressured by the Becks, wanted him to pay with his life, since his intended victim, Jim Kesterson, was White. Those kinds of jurisdictional conflicts were common during the Indian Territory era. This particular conflict turned bad.

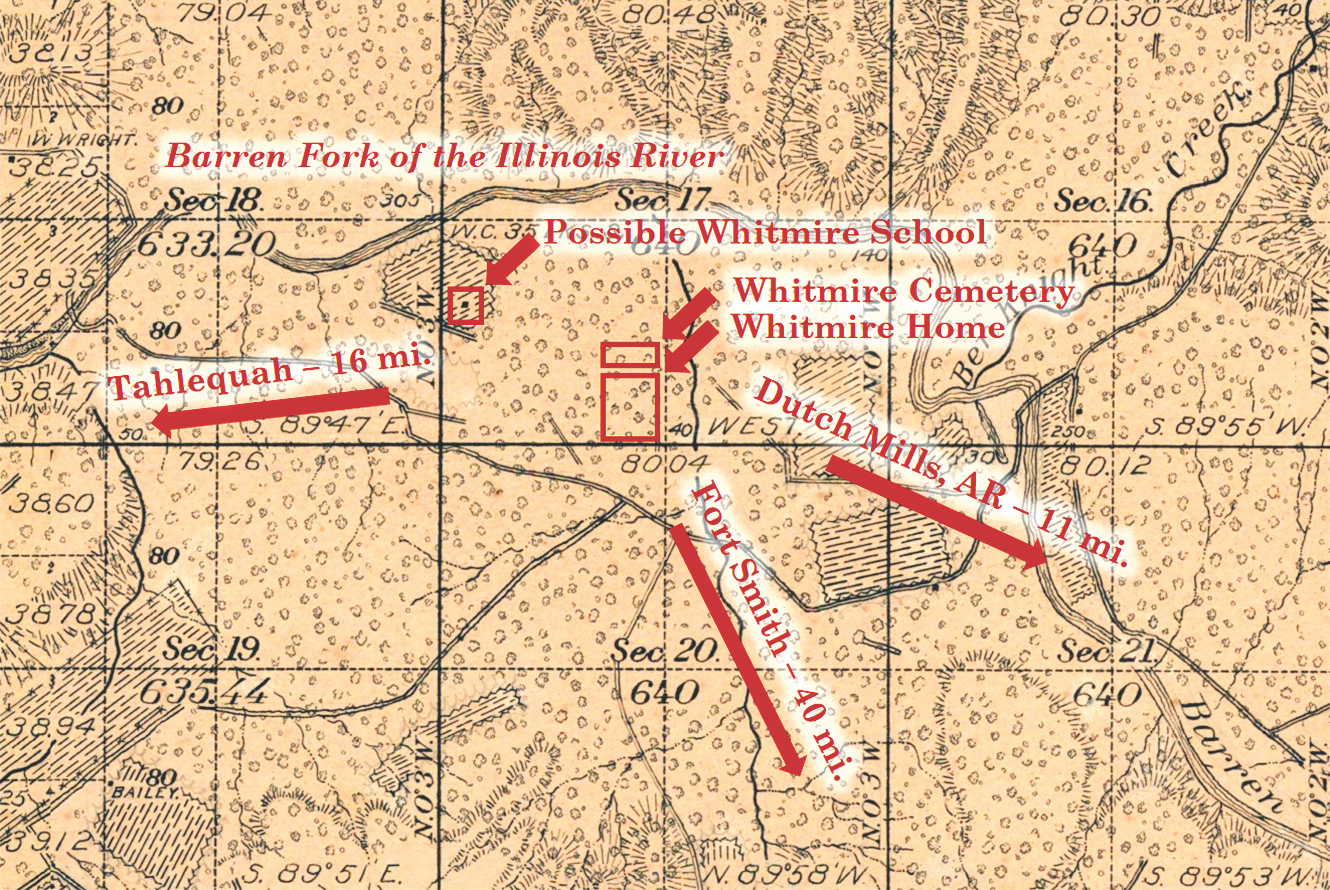

Proctor surrendered to the sheriff and asked for an immediate trial in the Cherokee courts. It was scheduled for April 15, 1872, in a house near present-day Christie, Oklahoma. But on the day of the trial, the proceedings were moved to a schoolhouse located in the Goingsnake District, which would give the upcoming incident its name.

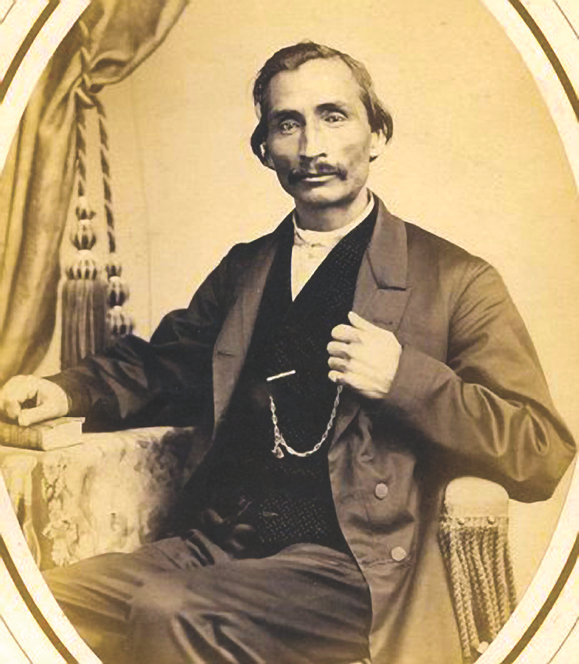

Polly’s kin were upset by the court arrangements. Too many of the locals were related to Proctor, including Cherokee Chief Lewis Downing. The Becks thought the only way to get justice, if they had to settle for that, was to have Proctor tried at the federal district court in Fort Smith, Arkansas. The U.S. authorities agreed. Deputy U.S. Marshals Jacob Owens and Joseph Peavey were assigned to retrieve Proctor.

But they made a bad decision. Knowing they might face some opposition, the officers put together a heavily armed posse of 15 men—featuring five members of the Beck clan who likely had blood, not arrest, on their minds.

The people attending Proctor’s trial were also armed; some say that included the judge, the attorneys and the defendant.

The two groups met when the posse approached the schoolhouse while the court was in session.

A Remarkable Force

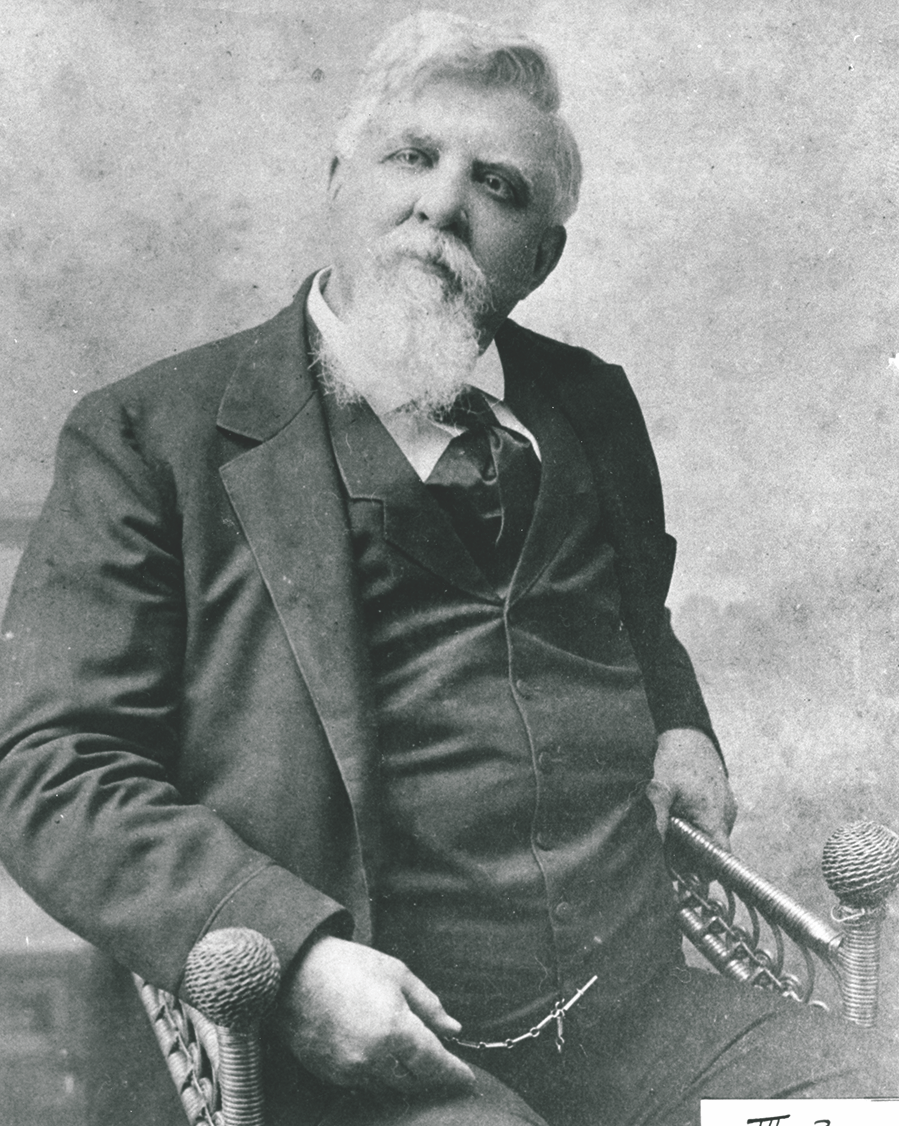

The Indian Territory Marshals were remarkable for their time and place. Even before Isaac C. Parker took virtual control of justice in the region as federal judge for the Western District of Arkansas in 1875, people of color wore the badge.

Blacks, Indians, mixed races—color didn’t matter that much when hiring the federal lawmen. Historian Art Burton, who has written extensively on Black and Indian territorial lawmen, estimates that upwards of 50 men of color served the U.S. Marshals Service in the region during the Old West period. Records aren’t clear; race wasn’t noted on enlistment or other employment documents.

During his 21 years on the bench, Judge Parker encouraged that hiring practice. Many of the Blacks and Indians had grown up in the territory. They knew the geography, the culture, the language and the people, giving them an on-the-job advantage, especially since the job was primarily “in the field.” Most of the time, officers delivered legal notices and documents, investigated crimes, rounded up witnesses and transported them to court, and, of course, arrested suspects. They rarely had to deal with train or bank robbers.

Anecdotal evidence indicates the marshals frequently focused on the selling or manufacture of liquor (illegal in the territory), timber poaching, Whites settling on Indian lands, rustling and counterfeiting.

All of which makes the attempted arrest of Proctor a bit out of the ordinary. The result was even more strange.

An Arrest Gone Wrong

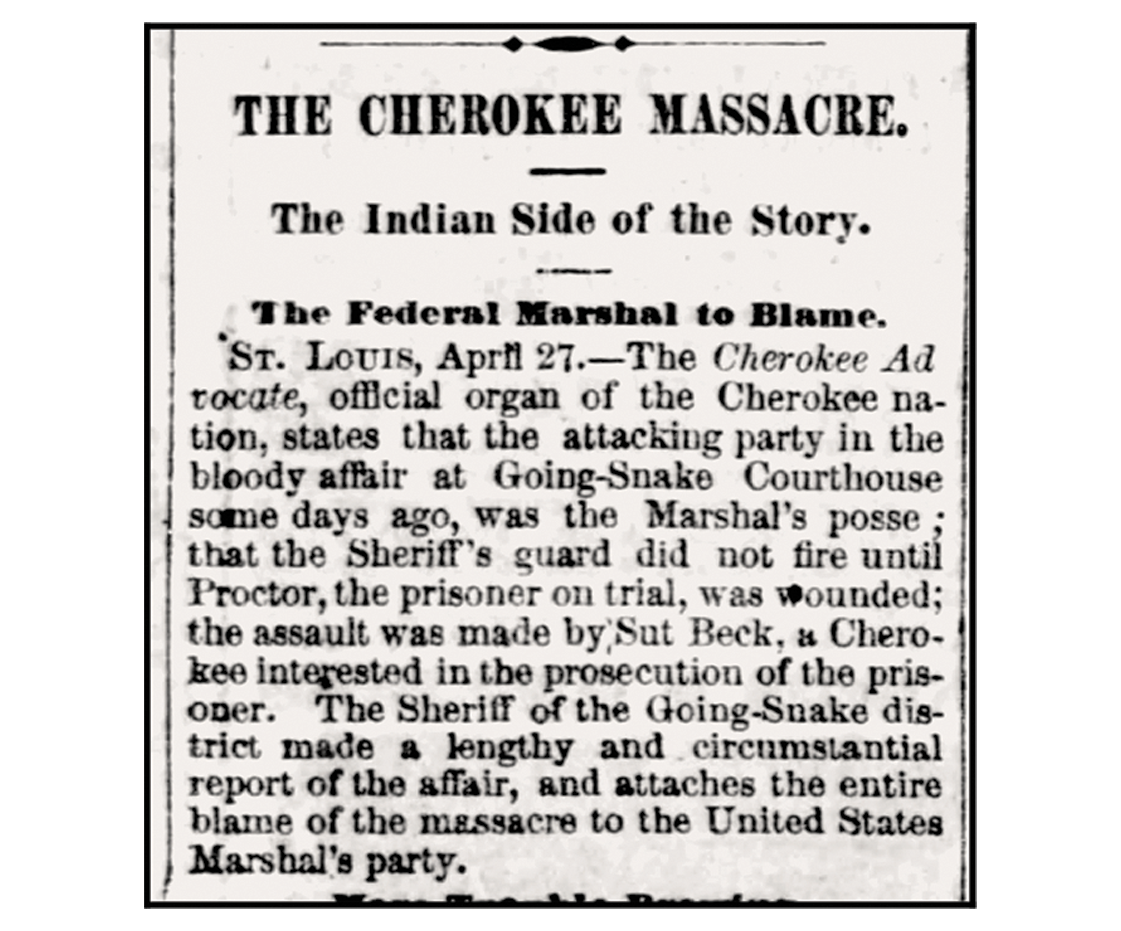

In many Old West gunfights, history is unclear on who fired the first shot, and little is known about the incident at the schoolhouse in Goingsnake.

When the posse rode up, court participants and attendees—about 15 people—heard them and gathered at the door and windows. Another 30 folks, mostly Proctor supporters, gathered outside. It’s believed that posseman White Sut Beck tried to push inside the building to take a shot at the defendant. Proctor’s brother Johnson pushed the barrel down just as the shotgun fired. Then the fight became general. Proctor reportedly fired away with a Spencer carbine. After a few minutes, when the smoke cleared, nine men were dead; two more died the next day.

The posse survivors made a hasty retreat eastward, followed closely by Proctor partisans.

Among those killed: eight members of the Marshals Service, including Deputy U.S. Marshal Owens, the largest single loss of life in the agency’s history. Three on the other side ended up dead, among them Proctor’s brother and his attorney.

Eleven more people were wounded, including Judge Blackhaw Sixkiller and Proctor.

Word of the disaster spread quickly.

The Marshals Service collected another posse to arrest the men who had killed their agents. The Cherokee court—attended by most of those wanted for taking part in the gunfight—reconvened the next day at a nearby house.

After a quick hearing and deliberation, the jury acquitted Proctor in the shooting of Polly.

Proctor headed to the hinterlands of the Indian Territory—reportedly accompanied by 50 heavily armed Cherokees.

Others from the erstwhile court also went into hiding until things had cooled off.

Federal authorities asked Chief Downing to turn over Proctor and the others for the marshals incident, but he refused, saying that the tribe would handle the matter. The tribe wanted to prosecute the surviving members of the posse, but federal officials were reluctant to hand them over. Finally, about 18 months after the tragedy, the two sides reached an agreement: charges against Proctor were dropped in exchange for the dropping of charges against the posse.

Nobody was tried for crimes committed during the Tragedy at Goingsnake.

Injustice Reigns Here

Many members of the Marshals Service died in the Indian Territory. For them, justice was hard to come by.

During Judge Parker’s time on the bench, when 79 men were hanged for the capital offenses of murder or rape, only five were executed for killing marshals. A sixth, Crawford “Cherokee Bill” Goldsby, was convicted of killing a deputy U.S. marshal during an escape attempt, but he was hanged for another murder.

In case after case, killers went free—either they were never captured or juries acquitted them of their crimes. In other cases, assailants got off with light sentences. Notorious robber Henry Starr killed Deputy U.S. Marshal Floyd Wilson during an attempted arrest in December 1892. Starr finished the lawman off with a point-blank, coup de grace shot to the chest. After a number of appeals and reversals, the killer pled guilty to manslaughter and served five years in prison.

Of course, some of the killers were captured but never made it to Fort Smith alive.

Why the leniency?

Many jurors had little love for lawmen (they also disliked outlaws), and that may have played a part. In some cases, the killings occurred in such remote locations, with little evidence and no witnesses, that the jury could not be convinced to hand down a heavy penalty.

For the dead lawman, his loved ones would not receive a pension or insurance money. The government generally didn’t pay for a funeral. And all too often, the family received no justice for the loss of a man who died while protecting the community at large.

A Cherokee Hero

Proctor still had a mark left to make in the Indian Territory. He continued to serve as a local lawman. In 1877, his peers elected him to serve as Cherokee senator from the Goingsnake District. To many of his people, he was a hero.

What’s most surprising, perhaps, was that in 1891, Proctor was hired as a deputy U.S. marshal, a post he held until around the turn of the 20th century.

He died of pneumonia in his own bed in February 1907; he was 76. His body was buried in a family plot, not far from where he had accidentally shot and killed Polly, and just a few miles away from the site of the Tragedy at Goingsnake.

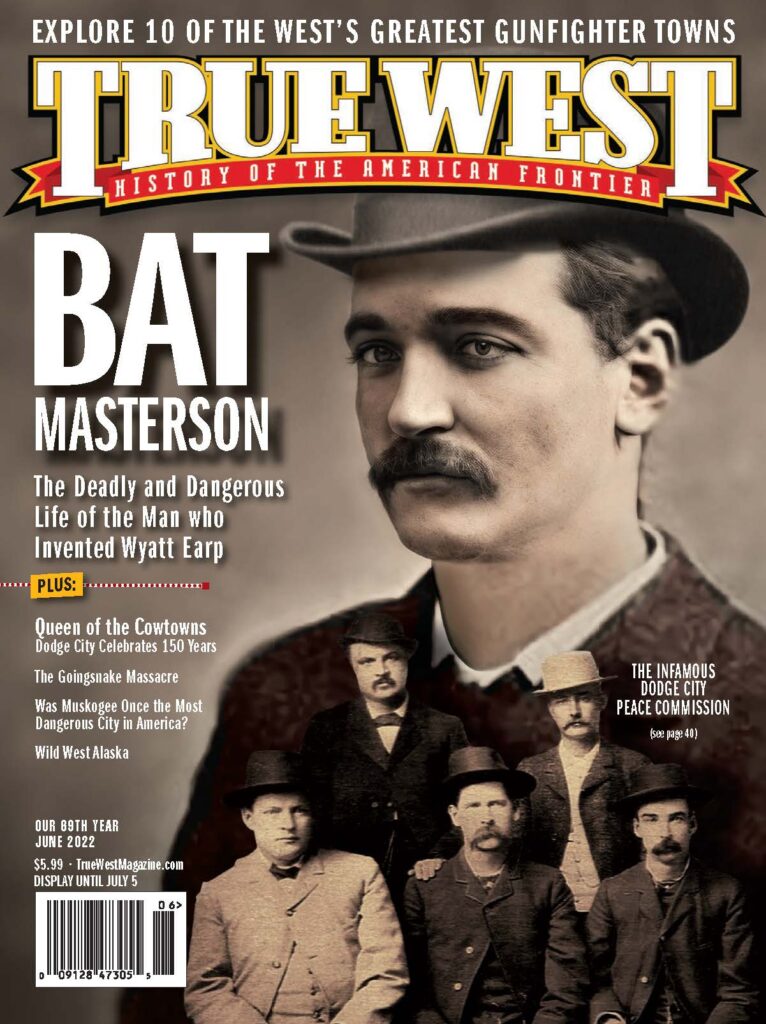

Mark Boardman is the editor of The Tombstone Epitaph and Features Editor of True West. David Kennedy is curator of Collections and Exhibits at the U.S. Marshals Museum.