Adventure and history await discovery across the Last Frontier State.

Courtesy Yale University

Several years ago, I was a long-term substitute teacher in the Yup’ik Alaska village of Akiak when the generator broke down. It was February and the village had no heat and no lights. I crawled into my sleeping bag wearing my coat, a little worried about hyperthermia. The forecast called for a low of minus 30.

I was drifting in and out when I heard barking. Wolves were coming in for the dogs. Lights usually kept the wolf pack from entering the village, but the easy meal the dogs made was too hard for the wolves to resist now that the village was pitch black. Suddenly a shotgun blasted, followed by another. Yup’iks were not about to lose part of their dog teams to wolves.

I got up around 6 a.m. trudging through snow to the school to get ready for my class. The air was crisp to the point of being painful. Moonlight was illuminating my breath. I heard a chopping sound. I could make out an elderly woman to my left wearing everything she could find to stay warm as she chopped firewood for heat and cooking.

My replacement flew in that afternoon, and I showed him around the village. He thought he saw a caribou skin stretched out across the side of a cabin. It looked odd to me until we got closer. It was a wolf pelt. There was a Native woman in the doorway braving the cold for a smoke. She said a hunter had brought it in from the tundra a few days earlier. Another woman had taken it into her cabin, thawed and skinned it, and then tacked it up to dry.

When we walked away, my replacement asked if I ever planned to come back to Alaska. I always come back, I said. It is as close as I can ever get to how the Old West really was.

The Yukon Beckons Adventurers

People come to Alaska to experience a past that built their national character, constructed the American DNA.

Poet Robert Service described those who went to Alaska as a “race of men who don’t fit in.” A friend living in Denali said Alaskans are the wanted and the unwanted. They were men and women who only felt comfortable living on the edge of society, moving farther and farther out until they fell off the map.

Robert Service was one of these wanderers. In 1904, he was northbound for Yukon Territory when he got off at Juneau for a few days. He wandered into a watering hole called the Missouri, today’s downtown Imperial Saloon, lingering long enough to witness a gunfight. It became the basis for his poem “The Shooting of Dan McGrew.”

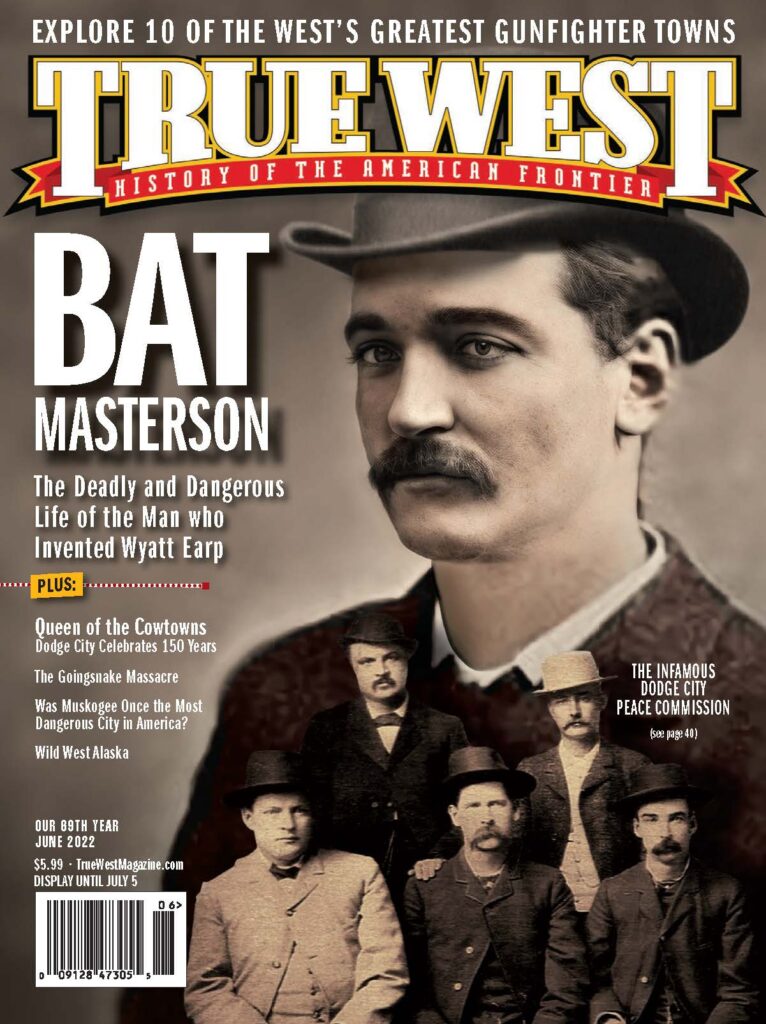

In 1897, Wyatt Earp got out of Wrangell, Alaska, after being marshal for only 10 days during the Klondike Gold Rush. The Soapy Smith gang had chased out the previous lawman, and while passing through en route to the Klondike, Earp agreed to take the job until the new marshal arrived. Once the lawman stepped off the boat, Wyatt and Josie were out of there, bound for Dawson City. The Earps would winter in Rampart, as the Yukon River was frozen over. They would make it to Nome in 1898.

By the docks and down the street from Juneau’s Imperial Saloon, the Red Dog Saloon has the legendary “Wyatt Earp pistol” mounted on the wall. While the Smith & Wesson No. 3 has attracted notoriety for a century, Earp and Josie were a 1,000 miles away in Nome. Nearby, the Alaskan Hotel was opened during the gold rush. The owners tied the front door keys to a balloon, releasing it into the air declaring the Alaskan would never close. It never did, but locals believe it is haunted by those who failed to earn passage home.

Over the bridge to the town of Douglas, one can walk the ruins of the Treadwell Mines, once the richest gold mine in the world. Take the state ferry LeConte to the town of Tenakee Springs. The actual hot springs is next to the wharf. Gold rush miners wintered here for years with their “winter wives,” prostitutes who cohabitated with miners in winter, keeping house for a cut of their gold.

Or take the ferry north to Glacier Bay. Besides lodges, there are campgrounds within the park. Here John Muir did studies in 1879 on glaciers while crying out for the preservation of Alaska. Army Lt. Charles Erskine Scott Wood discovered Glacier Bay in 1877 after being chased here by a rare Glacier bear. He had been guiding the Charles Taylor Expedition to the 18,008-foot Mount St. Elias, then believed to be the highest peak on the continent.

Taylor finally gave up returning to Sitka. His Tlingit porters scattered when they saw the Glacier bear, no relation to Canada’s creamy white Kermode “ghost bear.” Wood played medicine man for the Huna Tlingits before returning to Sitka with the chief’s daughter. Two years later, he was in Montana standing next to Gen. O.O. Howard recording Chief Joseph’s immortal words, “From where the Sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

National Park Service employees spot the rare Glacier bears now and then around the famed bay. There is also one mounted in the lobby of the Sitka airport.

Continuing north, Haines is the home to the 4,000-acre Fort William Seward. The last of 11 forts built in Alaska during the Gold Rush, Fort William Seward, with its 85 wood frame structures, also served as a deterrent during the border dispute with Canada that was not resolved until 1903. Haines is also the starting point for the Dalton Trail. The trail served as a freighting route to the Klondike in 1899. Constructed by Jack Dalton, along with a series of trading posts, it was a toll road, enforced by Dalton’s six-shooters.

Jewel of Frontier Alaska

The gem of Western lore, though, is Skagway.

A young Jack London landed in Skagway in 1897. He found Skagway to be made up of muddy streets lined with tents and shacks. Gunfire filled the air. Prostitutes conducted business in public view. North West Mounted Police Superintendent Samuel Steel called Skagway “little better than a hell on earth.”

London and others found refuge inside the Red Onion Saloon, still in operation today. It had been a brothel as well back then. A patron would choose one of 10 dolls behind the bar. When he went upstairs with one of girls, the bartender would lay the doll down to show that the girl it represented was occupied.

An epic land like Alaska needed an epic outlaw. Skagway’s Jefferson “Soapy” Smith filled the bill. A con man from Colorado, Smith with his gunmen controlled a number of Skagway’s saloons as well as in Wrangell. They robbed would-be millionaires along the Dead Horse Trail leading to the Klondike.

Smith made the con game an art form. He opened a visitor’s bureau handing out free maps with campsites marked. His men then waited at the marked campsites to rob them.

His best scam was the Dominion Telegraph, which amounted to an office with a copper wire running from it to a tree a mile out of town. For five dollars, people arriving could send word home they had made it. There was always a reply: A fake message telling the sender things were bad back at home asking for money to be wired immediately to help out, which they usually did from the fake telegraph office.

Smith’s stealing and killing caused returning prospectors to avoid Skagway, reducing business for others in town. A citizens’ meeting was held, and engineer Frank Reid and Jesse Murphy agreed to do the deed. On July 8, 1898, at 9:15 p.m., Smith, Murphy and Reid shot it out on the Juneau Wharf. Reid wounded the con man Smith, and Murphy finished Smith off with a shot in the heart. Before he was killed, Smith got Reid in the groin. Soapy died instantly from Murphy’s fatal shot, while Reid died days later in intense pain.

Both are buried in the Skagway cemetery along with prospectors and ladies of the evening.

Others who walked Skagway’s wooden boardwalks include madams Honora Ornstein, known as Diamond Lil Davenport, and Mattie Silks; Sid Grauman, who later opened his Chinese Theatre in Los Angeles with Klondike gold; Wilson Mizner, who opened L.A.’s Brown Derby; Augustus Mack, who founded Mack Trucks; and Wild West showman/gunman Charlie Meadows.

Capt. Jack Crawford, the Poet Scout of the West, who rode with Col. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok, went through Skagway to the Klondike Gold Rush sporting a white goatee, long hair and a buckskin shirt and ended up selling everything from ice cream to hay out of his store in Dawson called The Wigwam. The Klondike reminded him so much of the Old West he wrote his old friend Buffalo Bill about coming north to participate in all the fun.

Nearly all of Skagway’s gold rush buildings are still standing, including the Red Onion and Soapy’s saloon along with the impressive Arctic Brotherhood Hall constructed from 8,800 pieces of driftwood, all part of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park.

The Earps made it to Juneau but turned around and returned to San Francisco after Josie had a miscarriage. But Wyatt decided to make another go for Alaska, this time on the derelict freighter S.S. Brixom. Sadie boasted that Wyatt helped put down a mutiny before changing ships at Dutch Harbor. At Saint Michael, they took a riverboat bound for the Klondike, but became iced in until sourdough legend Al Mayo rescued them and had them stay over the winter. At Mayo’s, they met Tex Rickard, future Madison Square Gardens owner; noted bootlegger Charlie Hoxie; and soon-to-be novelist Rex Beach.

Spring found the Earps back at Saint Michael with Wyatt managing a canteen selling cigars and beer until Hoxie’s and Rickard’s letters enticed them to the Nome Gold Rush. The Saint Michael cabin the Earps lived in is still in use as a residence today. In Nome, Wyatt partnered with Hoxie to open the only two-story Dexter Saloon in Alaska. Earp and Rickard staged boxing matches when the long winter hit, along with drinking contests and food drives. Earp was on the watch committee keeping an eye out for claim jumpers and was arrested once for interfering with a local law officer.

Legend has it the Earps left Nome (and Alaska) in 1900 with $85,000 when Earp sold out his piece of the Dexter. It was Wyatt’s most successful venture—ever.

Stepping Back in Time

Echoes of the Old West can be found along the Chena River in downtown Fairbanks, where low-roof log cabins dating back to its gold rush line the banks. Cordova, though, holds a real gem from the Old West. Besides the massive rosewood bar inside The Alaskan, there’s the Red Dragon. On a hill overlooking downtown in ornate Edwardian style, the landmark was built as a place where alcoholics and drug addicts could dry out. Local historians claim mountain man Yellowstone Kelly was once a tenant. He had come north with the Harriman expedition in 1899. Today, the Red Dragon serves much the same purpose. You’d be advised to knock first before entering.

A chain of roadhouses where a traveler could get warm, have a meal and a night’s sleep while his dogs and horses were tended to used to dot Alaska’s arctic trails. Some are still standing. Rika’s Roadhouse at Delta Junction is now a museum and restaurant. Admission is free. Built in 1904 and operated by Rika Wallen until her death in 1969, it is a prime example of what an Alaskan roadhouse was all about.

Other historical roadhouses still in operation are Copper Center Inn in Copper Center, Gakona Roadhouse in Gakona, Talkeetna Roadhouse in Takeetna, Sheep Mountain Roadhouse in Sutton and Eureka Roadhouse in Glennallen, known for its pies and 25-cent cup of coffee.

A thousand miles to the west on the raw, windswept Unalaska Island, prospectors going to Nome by ship attended dances held in the three-story North American Commercial Building. In 1890 these dances were hosted by one of the few women living in Unalaska, Mollie Stanley-Brown, the daughter of assassinated President James A. Garfield.

Mike Coppock was born and raised in Western Oklahoma, and after graduating from Phillips University in Enid, has lived off and on in Alaska since 1985. In Alaska he has taught history in an Alaska Bush community, worked as an editor of two Alaskan newspapers and was a flight specialist for the FAA. He is currently a historical interpreter at Denali National Park.