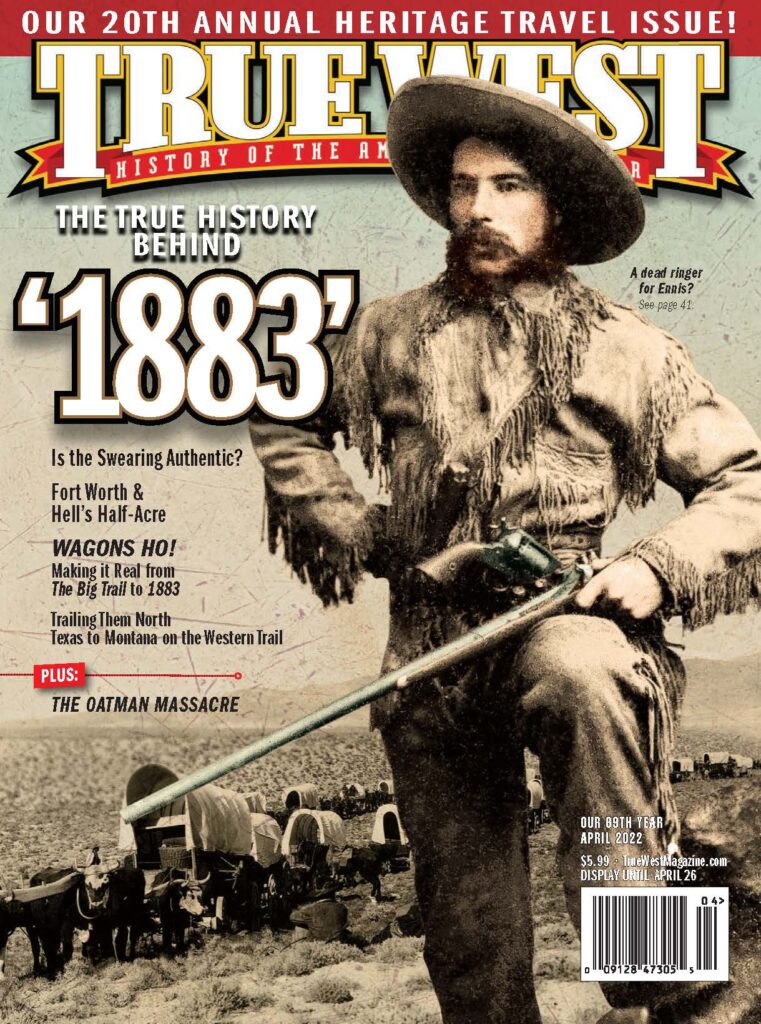

Innovative filmmaker Taylor Sheridan’s new series captures the grit and the glory of the trail.

When True West spoke to creator Taylor Sheridan in August of 2021, on the eve of principal photography, no one knew how 1883 would turn out, or how the public would respond to it. At this writing, the last few episodes have not yet aired, but the audience has spoken: 1883 had the biggest cable premier since 2015, and the numbers remain high. The Yellowstone prequel, which follows the wagon trip west by the current Duttons’ great-great grandparents, has been called the best miniseries since Lonesome Dove.

“My reaction was surprise,” says film historian C. Courtney Joyner, “because it isn’t a gun ’em down Western story, it’s a pioneer story. A wagon train story. That’s really cool because it’s an area that has not been touched in decades.”

The series has scored well with the much-desired younger-adult demographic, perhaps because the subject matter is surprisingly familiar to them. Since 1971, 65 million copies of The Oregon Trail, the computer game and school staple, have been sold. Still, that’s not television. “No one’s made the ‘wagons West’ story in a way that’s really been impactful,” notes Sheridan. True, no one’s done it in a long time. But it has been done brilliantly twice before: 1923’s The Covered Wagon and 1930’s The Big Trail have set the bar dauntingly high.

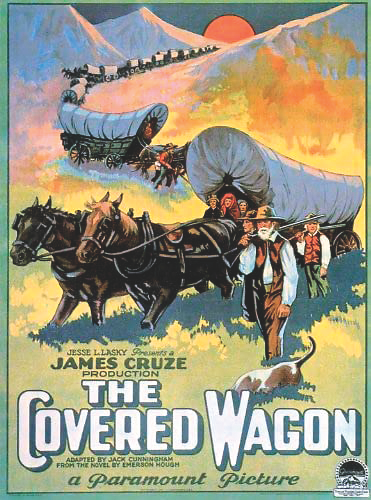

Both films are epics—with casts and crews in the thousands, beautiful locations and wonderful directors—James Cruze and Raoul Walsh, respectively. Visually enthralling—Covered Wagon was filmed by D.W. Griffith’s cameraman Karl Brown, and Big Trail was shot in a 70mm format—they are thrilling to watch even today.

Of course, beyond the enormous budgets, those filmmakers had an advantage over Taylor Sheridan. Says Joyner, “The filmmakers were in a time when these were actual events. The breaking of the West was only 60 years before they made the movie. They had Civil War veterans in those movies.” In fact, the nearly 100 prairie schooners in Covered Wagon were genuine relics of the wagon trains, many driven by owners who had made the trip as children.

It’s worth noting a scene that occurs five minutes into Covered Wagon. As the pioneers wait impatiently to begin their trek, admiring a plow, the scene dissolves to a title: “Far out on the westward trail stands another plow that bravely started for Oregon.” It’s being examined by several Indians. One says, in a title card, “this monster weapon will bury the buffalo—uproot the forest—and level the mountain. The Pale Face who comes with this evil medicine must be slain—or the Red Man perishes!” There is no parallel in any other film on the subject.

Ironically, while Wagon was a hit, the equally magnificent Trail was a bomb: only two theaters in America could run the wide-screen format, so few saw it, and its star, young John Wayne, was blamed, and sentenced to nine years at Republic Pictures.

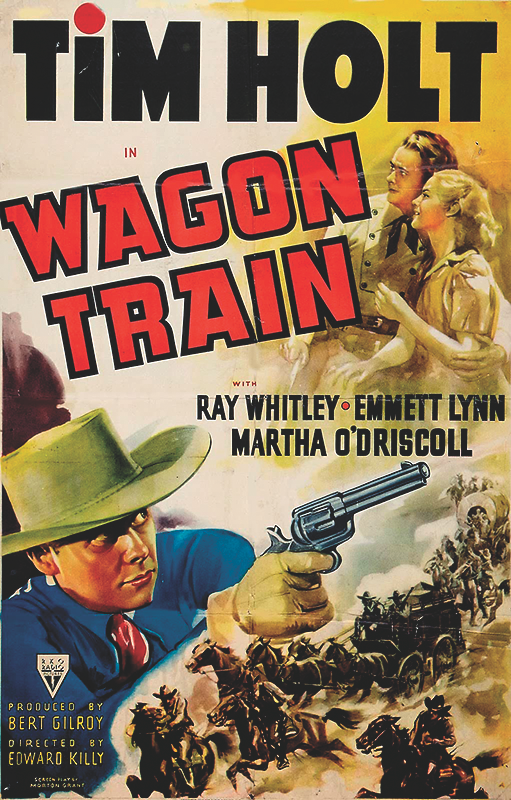

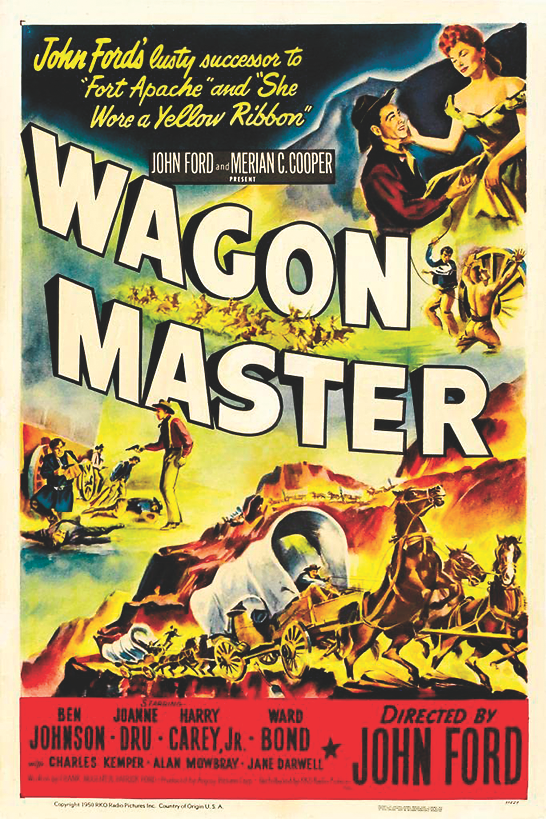

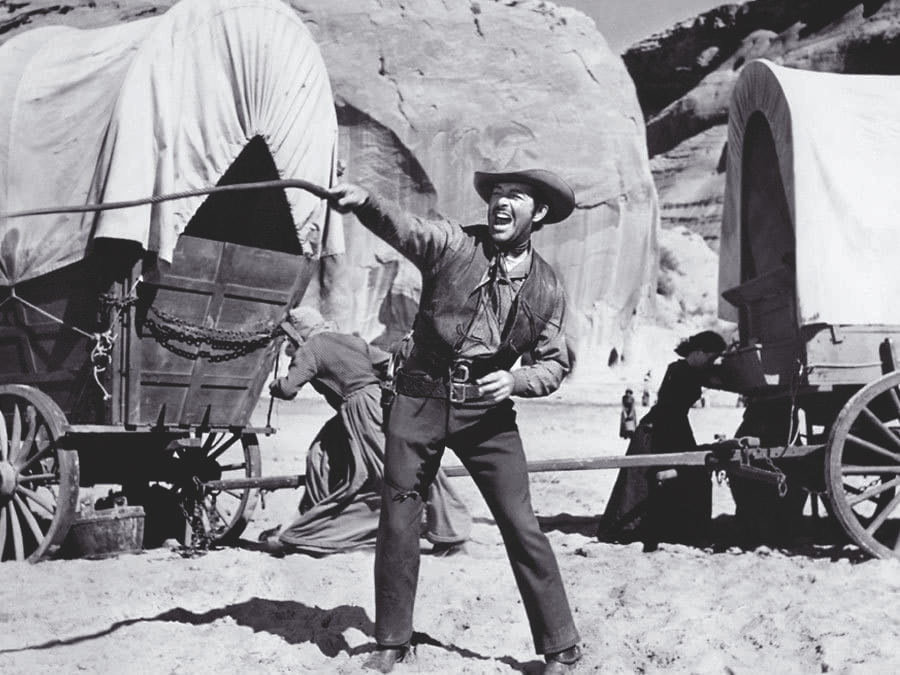

But 20 years later, the story of the wagon trains returned with John Ford’s small but excellent Wagon Master, starring Ben Johnson and Harry Carey Jr. as horse-traders reluctantly roped into leading a Mormon group to their promised land. Its third lead, Ward Bond, who’d been unbilled in Big Trail, would become a star as Major Adams on the tremendously popular series, Wagon Train.

A year later, Westward the Women, written by Frank Capra and directed by William Wellman, became the best and toughest of the later wagons West films. Robert Taylor’s wagon master leading a caravan of women has much in common with 1883’s Sam Elliot doing the same for a group of ill-prepared German immigrants. Both men are as hard and mean as it takes to get the job done and willing to kill pioneers who don’t follow their rules.

The other wagons West films all have their virtues. Disney’s Westward Ho, The Wagons features an Indian attack, directed dynamically by Yakima Canutt, which was much-improved when Walt let him reshoot it, allowing Indians and settlers to actually get hurt. Andrew McLaglen’s The Way West, though ruined by the studio cutting 20 minutes from the opening, has great sequences, including the rope-lowering of wagons from cliffs to the valley hundreds of feet below, although it can’t compete with The Big Trail’s enormity: ten wagons lowered at once, with children being handed down on ropes in the same shot.

As Sheridan explains, telling these stories well begins with knowledge—of the history and of filmmaking. “You go back to John Ford, Ben Johnson. Everyone knew a lot more back then and knew how to film it. Now you’ve got people trying to make Westerns who have never seen a horse in person. Whenever I write anything, I have to factor in first and foremost, is it achievable? I operate from that standpoint.” And, yes, with 1883, Taylor Sheridan has achieved something wonderful.

Henry Parke is a screenwriter, author and True West’s Film and television editor.