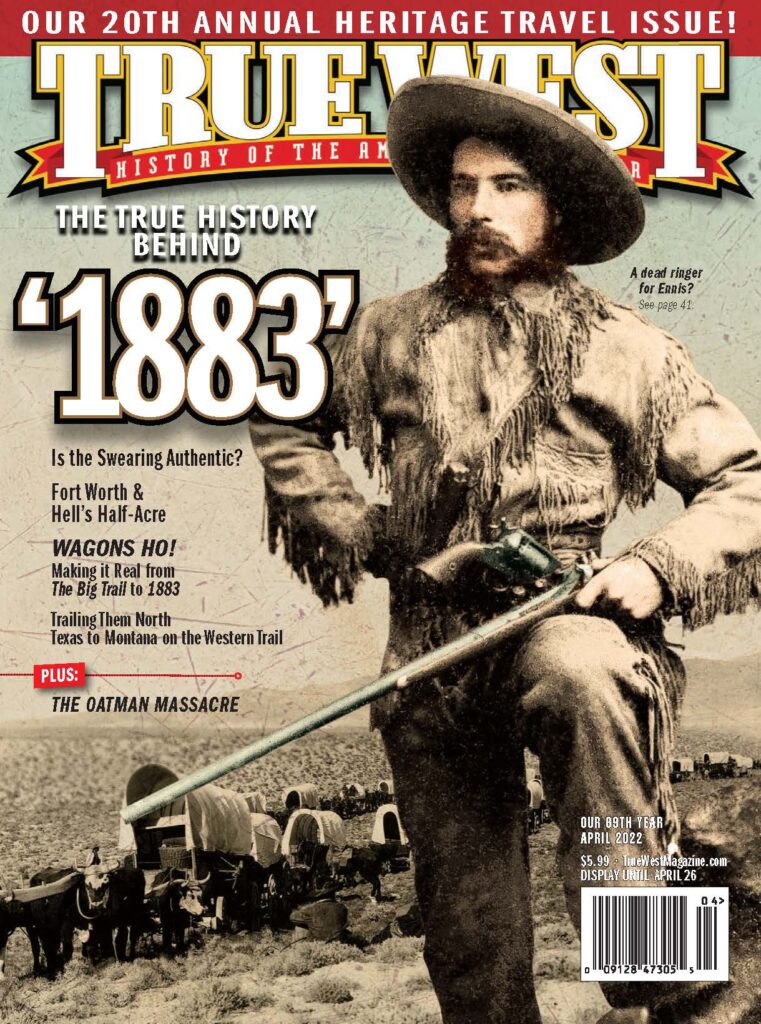

Follow the Western Cattle Trail from Bandera, Texas, to Miles City, Montana.

All Images by Johnny D. Boggs Unless Otherwise Indicated

Blame it on Babesia bigemina.

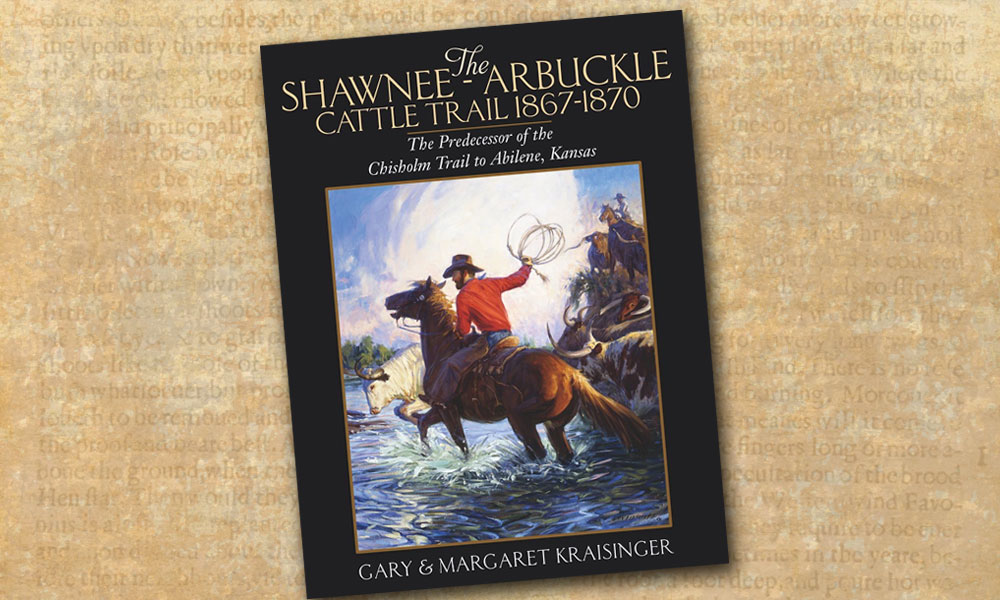

That little parasitic protozoa found a home in ticks, which found a home on Texas longhorn cattle, until the bloodsuckers jumped to new digs on domestic cattle in present-day Oklahoma, Kansas or Missouri—and pretty much brought an end to the Shawnee and Chisholm cattle trails to Sedalia, Baxter Springs, Abilene, Ellsworth, Wichita, etc.

Kansas beef and Babesia bigemina did not mix. The cattle became feverish, lost weight, turned anemic, passed blood in their urine and died. Sick of Texans, Kansans established quarantine lines that prohibited herding Texas longhorns through civilized country.

Undeterred, Texas trail bosses simply moved west of the quarantine line—until Kansas eventually banned all Texas herds in 1885—said goodbye to the Chisholm Trail and inaugurated the Western Trail.

The eastern (Chisholm) trail crossed the Red River at Spanish Fort or Red River Station in Montague County. Some Texans continued that route into Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), then turned on the Dodge City Cut-off to avoid the quarantine line and angry Kansans. But soon a new trail emerged.

Texas

Also known as the Dodge City Trail, Fort Griffin Trail and Great Western Trail, the Western Trail began in South Texas. How far south depends on who you ask/read. Feeder trails ran like fingers, and routes often depended on where the best grass could be found. But a good place to start is Bandera, which lives up to its “Cowboy Capital of the World” moniker with the Frontier Times Museum, which J. Marvin Hunter started in 1927. Hunter earned his place of honor among cowboy chroniclers by compiling and editing The Trail Drivers of Texas, a collection of trail-driving cowboy memoirs first published in 1924.

A fair number of those cowpokes had Bandera County connections, which might explain why the Dixie Dude Ranch first opened in 1937 and many others have followed.

The trail generally moved north to Kerrville (Museum of Western Art) and Junction (Kimbell County Historical Museum) before crossing the San Saba River at Pegleg Crossing east of Menard (Menardville Museum). From there, cowboys and cattle continued north, passing east of Abilene (Frontier Texas!), which took its name from the Kansas cowtown of Chisholm Trail fame.

Cowboys kept pushing those dogies north to Albany (The Old Jail Art Center), Fort Griffin (Fort Griffin State Historical Park), Seymour (Baylor County Museum) and Vernon (Red River Valley Museum). North of Vernon, longhorns, horses, chuckwagons and cowboys reached the Western’s most famous location in Texas: Doan’s Crossing on the Red River.

“The first house at Doan’s was made of pickets with a dirt roof and floor of the same material,” Corwin F. Doan recalled. “The first winter we had no door but a buffalo robe did service against the northers.”

Doan and his uncle, Jonathan Doan, set up the trading post just south of the Red in 1878—roughly four years after John T. Lytle blazed the Dodge City/Fort Griffin/Western Trail by pushing a large herd of cattle from South Texas to the Red Cloud Agency in Nebraska.

“By the late seventies,” Ida Ellen Rath wrote in The Rath Trail, “the Texas cow punchers were driving tens of thousands of longhorns over this Western trail.”

After stocking up on supplies, the cowboys crossed the Red into Indian Territory.

Oklahoma and Kansas

“We kept our eyes open and managed to keep peace by giving [Indians] a beef every day,” F.M. Polk remembered. “They would come to us fifty and one hundred at a time. Some would ride with us all day and they always asked for a cow…and, of course, we acted like we were glad to give it to them….”

Oklahomans put the trail along U.S. 183—Frederick (Pioneer Townsite Museum), Hobart (Kiowa County Historical Museum), Clinton (Washita County Museum)—or Oklahoma 34—Altus (Museum of the Western Prairie), Elk City (Old Town Museum), Woodward (Plains Indians & Pioneers Museum). Well, ramrods could pick their own paths, and better grass trumped crowded trails.

Either way, the herds eventually hit Fort Supply (Fort Supply Historic Site) before striking Kansas and, for a while, no quarantines.

The trail’s early destination was Dodge City (Boot Hill Museum), the last of the great Kansas cowtowns. “Those of long experience in the West do not need to be told that the depraved of both sexes flocked to this ‘wild and woolly’ frontier settlement,” the New York Times wrote of Dodge City in 1889. “Twenty years ago there was a class of vicious people west of the Mississippi River, whose mission it seemed to be to settle in every new town if for only a few days or hours. There were, apparently, as many women as men in the villainous tribe which swooped down upon Dodge as soon as its name became known among the great Western trails.”

The trail continued into Nebraska past present-day Crawford (Fort Robinson History Center) to the Union Pacific Railroad at Ogallala (Boot Hill Cemetery), where more cowboy debauchery awaited the young Texans.

“The sharpers and gamblers who have reached Ogalalla [sic] from various points are always ready to accommodate the cow-boys in their search for ‘amusement,’ and they are fortunate if they do not leave a considerable of their wages with the Spanish Monte and Faro dealers,” an American Agriculturist correspondent observed in 1879.

Pointing ’em north

But the Western Trail wasn’t finished. Many drivers herded beef north into Deadwood (Adams Museum) and the Black Hills of present-day South Dakota. Another branch turned northeast from Ogallala bound for grazing land and ranches in Wyoming and Montana. The later trail went through present-day Rusk, Wyoming (Stagecoach Museum), and finally ended at Miles City, Montana (Range Riders Museum).

“If the importance of a cattle trail is to be measured by the number of animals passing over it on their way to market,” Henry Sinclair Drago wrote in Great American Cattle Trails, “then the Western Trail was second only to the Chisholm as the greatest of all American cattle trails.”

How’s that for anti-Western Trail bias! Estimates of cattle on the Chisholm Trail run around 5 million. And the Western? That’s 6 million to 7 million. Drago should have checked Paul I. Wellman’s The Trampling Herd. Wellman wrote:

“More has been written of the Chisholm trail than any of the other routes, but the Western trail and Doan’s Crossing in their day eclipsed that famous cattle highway.”

And all because of Babesia bigemina.

A Wide Spot in the Road

FORT PHANTOM HILL

Among Texas frontier forts, Fort Phantom Hill—aka “Post on the Clear Fork of the Brazos”—in present-day Jones County, Texas, is often overlooked. Established by five companies of the Fifth U.S. Infantry in November 1851, the fort quickly became known for hardships. Summers were brutally hot. Blue northers could turn the area into a freezing hell. And the water tasted awful. The post was abandoned in 1854, then became a station for the Overland Mail Company in 1858 before secession and Civil War stopped that route.

After the war, the buildings were used as a Fort Griffin subpost. The place still wasn’t inviting. A correspondent described the country in 1872: “Eight miles from Phantom Hill we came to a water hole, after which we had a dry road, dry and thirsty as an old soaker with money and credit all gone. For twenty-five miles we had no water. The country is hilly, yes, even mountainous, not very picturesque, nor inviting, the vegetation mezquit and Spanish dagger.”

Since 1972, the fort has been preserved on 38 acres northeast of Abilene on Farm-to-Market Road 600. The grounds are open daily dawn until dusk for self-guided tours. Admission is free. FortPhantom.org

Good Eats and Sleeps

Good Grub: O.S.T. Restaurant, Bandera, TX; Beehive Restaurant, Abilene/Albany, TX; White Dog Hill, Clinton, OK; Casey’s Cowtown Club, Dodge City, KS; Open Range Grill, Ogallala, NE; Sugar Shack, Deadwood, SD; Mint Bar, Sheridan, WY; Montana Bar, Miles City, MT

Good Lodging: Y.O. Ranch Hotel & Conference Center, Kerrville, TX; Historic Heritage Hotel, Dighton, KS; Bullock Hotel, Deadwood, SD; Sheridan Inn, Sheridan, WY; Horton House Bed and Breakfast, Miles City, MT