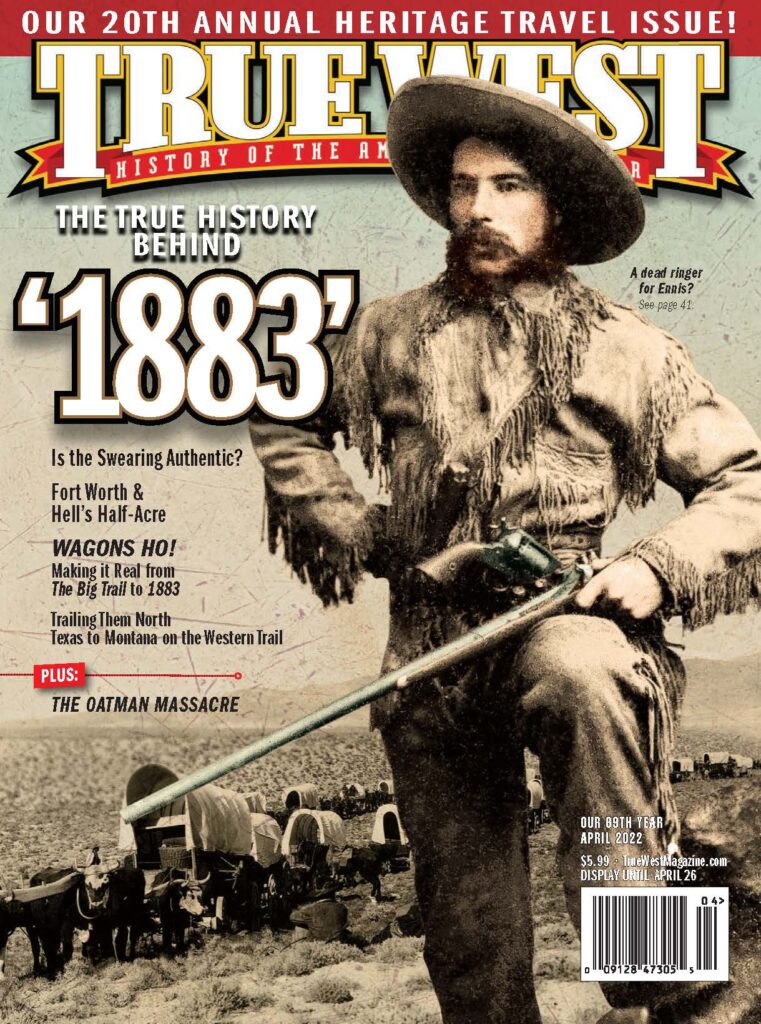

True West’s historians reveal the real history behind Taylor Sheridan’s 1883.

Hollywood producers, directors and writers have often attempted to re-create the grandiosity and pageantry of an epic period in history on the silver screen and television. From John Ford to Raoul Walsh, from Cecile B. DeMille to John Wilder, Hollywood’s most visionary mythmakers have entertained us all with big-production, as historically accurate-as-possible, sweeping ensemble Westerns. From The Iron Horse, The Big Trail, Arizona, The Searchers, Bend in the River, How the West Was Won and McCabe and Mrs. Miller to I Will Fight No More Forever, Centennial, The Sacketts, Lonesome Dove and Tombstone, producers have attempted to portray the West as realistically as possible.

Enter writer, director, producer and actor Taylor Sheridan. Until his recent success with Paramount’s award-winning series Yellowstone, the award-winning writer was best known for his critically acclaimed screenplays Sicario, Wind River (which he also directed) and Hell or High Water. With the critical and popular success of Yellowstone in the ever-expanding streaming marketplace, Sheridan realized the opportunity he had before him: to create and produce a set of series telling the incredible backstory of Yellowstone’s fictional Dutton family. Throw in the facts that Sheridan is a proud Texan, a great admirer and student of the Western genre—especially the high production value of Lonesome Dove—and you have the recipe for the creation of the Yellowstone origin story prequel, 1883—the largest and most expensive Old West television series ever produced.

At True West, we admire Sheridan’s ability to convince the studio and investors to help finance his production—which he has attempted to make as accurate as possible with the best creative team behind the creation of every wagon, costume, saddle, firearm and prop. Always remembering it is Hollywood entertainment, not a documentary, we want to offer our readers an insightful look—through our historians—into the real history that inspired Sheridan’s remarkable and entertaining Western series. And, as we are all fans of 1883 and the genre, we are hopeful that more studio executives will have the courage to greenlight more Western series and films and rejuvenate this grand American art form.

A Snapshot of the West – and America – in 1883

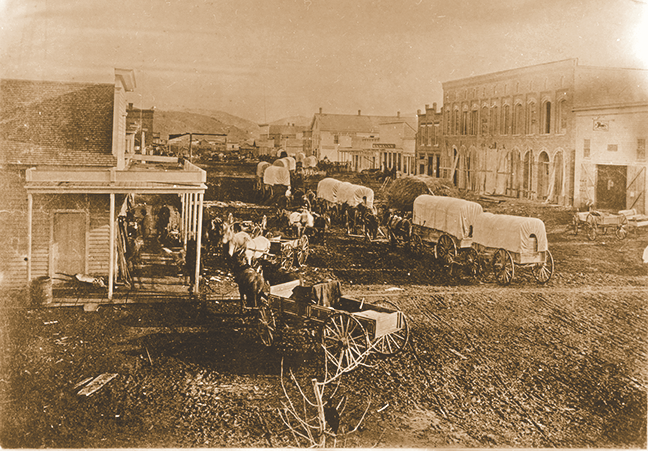

If you were an immigrant who stepped off a passenger ship in New York, New Orleans or Galveston with a train ticket to the West in 1883, this is the America you would discover:

• The population of the United States was approximately 50.2 million, Texas was 1.2 million, Montana 40,000 and Oregon 175,000.

• The President was Chester A. Arthur (R).

• There were 38 states, 10 territories and one military district, Alaska. Hawaii was not annexed as territory until 1898.

• The 1880s was the last great decade of emigrant wagon trains on the overland trails.

• The U.S. had four transcontinental railways and over 100,000 miles of railroad tracks.

• In 1880, 6,679,900 immigrants lived in the U.S.; ten years later it was 9,249,500.

• The three diseases that killed the most Americans were “diseases of the nervous systems,” tuberculosis and pneumonia.

- Fort Worth’s stockyards became a major cattle shipping point in the Lone Star State. Between 1880 and 1890, the cattle town, notoriously known for its “Hell’s Half Acre,” went from 6,663 residents to 23,076.

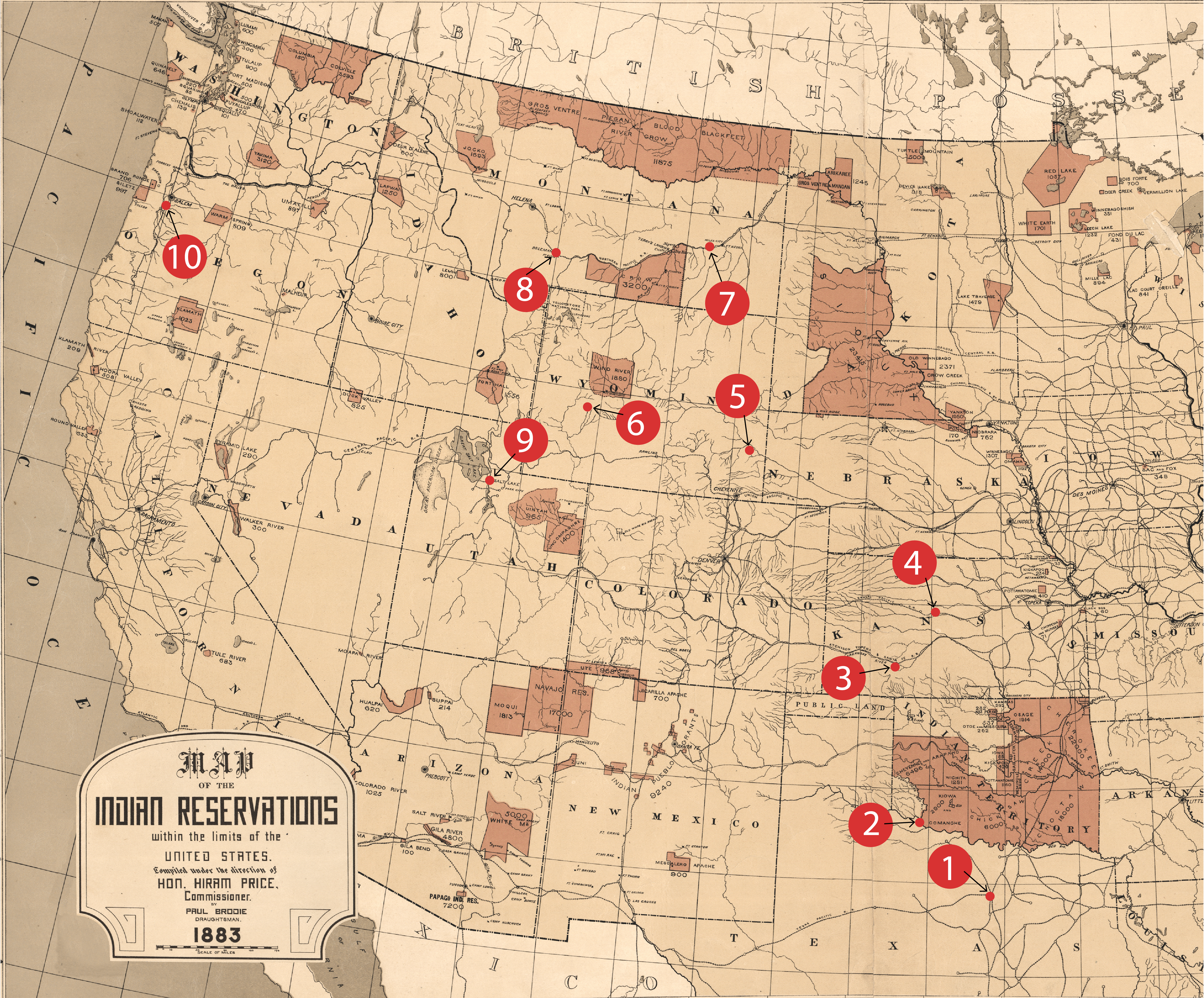

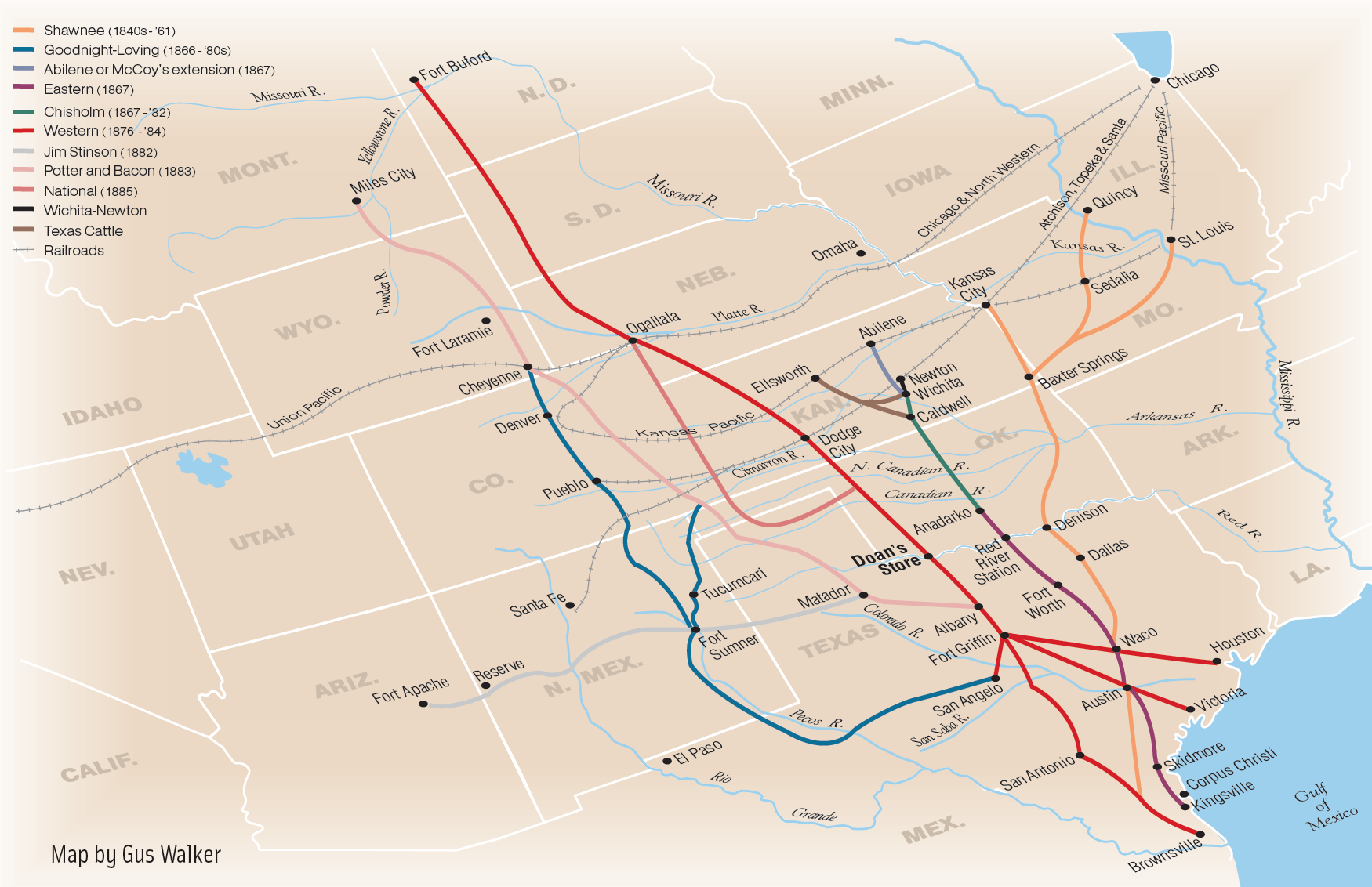

- Doan’s Crossing was founded by Jonathan Doan in 1878. For the next decade, a majority of Texas ranchers shifted from the Chisholm to the Western Trail, which headed north from Bandera and the Hill Country to Doan’s Crossing of the Red River. More than seven million head of cattle crossed the Red at the river’s ford, which was approximately 100 miles west of the Chisholm’s Red River Crossing.

Doan’s Store, Texas, c. 1880 - Dodge City was transformed from a dusty outpost of buffalo hiders to the “Wickedest Little City in America” after Kansas lawmakers moved the quarantine line for the tick-carrying Texas cattle so far west that Texas cattlemen were forced in 1876 to shift their drives to the Western Trail to Dodge City.

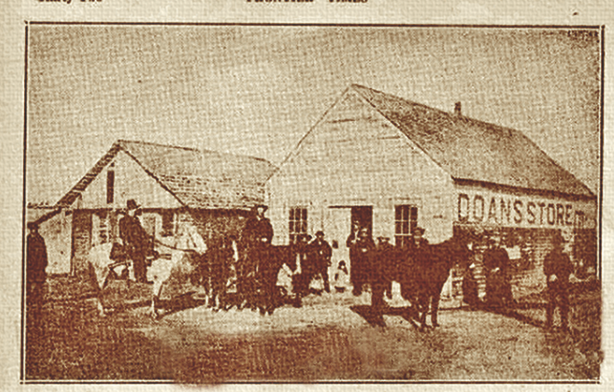

Abilene, Kansas, c. 1878 - Abilene became Kansas’s first “queen” of the cowtowns when the first Texas herds arrived in 1867 at the frontier village on the Smoky Hill River. Four years later, after more than 440,000 beeves were shipped out of the former stage stop, Texas drovers shifted their herds to new railheads in Newton, Ellsworth and Wichita.

- Fort Laramie on the Laramie River in east-central Wyoming was still a key frontier Army post and supply center for westbound and eastbound wagon trains, freighters and travelers in the early 1880s. In 1890, the fort

was closed and decommissioned. - South Pass remained the most important crossing of the Continental Divide of the Rocky Mountains in southwestern Wyoming for travelers on the Oregon Trail in 1883.

- Miles City, strategically located in the late 1870s at the confluence of the Tongue and Yellowstone rivers, was a frontier outpost for soldiers and traders and became a key Northern Pacific railhead in 1881-82 for Texas cattlemen who drove their herds over 1,500 miles up the Western Trail to Montana’s rich, open-range grasslands.

- Bozeman was incorporated in 1883, nearly two decades after John M. Bozeman founded it as the terminus of his self-named offshoot of the Oregon Trail west of Fort Laramie to Virginia City and the goldfields of Montana.

Bozeman, Montana Territory, c. 1880s - Salt Lake City was the capital of the Utah Territory and a key crossroads and supply center for Nevada-, California- and Oregon-bound emigrants since the Salt Lake Cutoff was created in 1850.

- Willamette Valley in western Oregon had been the primary destination for Oregon Trail emigrant settlers since 1841.

The End of an Era

by Johnny D. Boggs

Texans drove their last great herds north in the 1880s.

Kansans had been complaining about Texas longhorns since the first herds hit Abilene in 1867, but the trail-driving heyday kept booming, peaking in the 1880s.

Almost 350,000 Texas cattle reached Kansas in 1880.

Sure, Kansas established quarantine laws to prevent the spread of a tick-spread disease from coming up the Chisholm Trail. But there was still a market in Dodge City (1875-85) and Caldwell (1880-85).

Texas cowboys could follow the Chisholm Trail into present-day Oklahoma (then Indian Territory) and take the Dodge City cutoff to the Western Trail, aka “the old Fort Griffin and Fort Dodge trail.” As quarantine lines moved west, cattlemen recommended sticking to the Western Trail completely.

But ranches in Colorado, Wyoming, Montana and Dakota Territory also needed beef—to feed a growing population and to stock ranches. Texans herded cattle into Nebraska, Dakota Territory, Colorado, Wyoming and Montana.

Sure, railroads were crisscrossing much of the West by the 1880s. But Texas ranchers understood that outfitting a trail drive (say a cook, a horse wrangler, a trail boss and 10-12 cowboys) came a lot cheaper than paying the shipping prices railroads charged.

By 1882, packing houses were paying more than $7 per hundredweight for cattle, up more than $3 from 1880. The cattle business became a “gold brick,” Wyoming cattleman John Clay recalled. Foreign investors, mostly from Great Britain, began pumping money into American livestock companies.

Courtesy NYPL Digital Library

But things were changing.

In late November 1883, the Cherokee Strip Live Stock Association in Indian Territory posted notice to “drovers of Texas and Arkansas cattle, that a trail used in the summers of the years 1881 and 1882, by what are known as through cattle drovers, has been fenced by the members of this Association, and is included in pastures now stocked with domestic cattle, which renders it extremely dangerous to have this trail used by through Texas cattle.”

In 1885, the Kansas Legislature made the entire state off limits to Texas cattle.

That didn’t stop cattle from reaching Colorado, Wyoming and Montana. The Goodnight-Loving Trail, called the Goodnight Trail in the 1880s, was becoming popular for shipping cattle through West Texas and New Mexico Territory. But in 1886, even the Northern New Mexico Association was fed up with Texas cattle eating New Mexico grass on the way north. (Besides, New Mexicans had never cared much for the Lone Star State anyway after Texans launched invasions in 1841 and 1862.)

By the mid-1880s, Texas cattlemen lobbied for a national cattle trail, effectively “a permanent outlet to the northwest,” according to the Texas Live Stock Journal. A proposed trail, six miles wide, 1,500 miles long, did not please many non-cattlemen.

“They talk and talk and talk,” a correspondent covering a cattlemen’s gathering in St. Louis complained in The [New York] Sun in 1885, “and get reporters to interview them so that they can bore the public with their narrow views about the disposition that should be made of the public domain, as though it were of the slightest importance what a few hundred men—many of them not citizen—who have unlawfully seized the public lands, think should be done with the domain.”

Talks continued, however, and in March 1886 the Secretary of the Interior designated a strip two miles wide along the eastern Colorado border for the trail. But that was rescinded in June 1887.

What caused the sudden turnaround?

Mother Nature pretty much ended any further discussion.

Cattle prices dropped in 1885, then a severe drought struck in the spring and summer of 1886. The hard winter that followed in 1886-87 became known as “The Big Die-Up.” Some 25 percent of cattle on Colorado’s Front Range perished. Montana estimated cattle losses at 362,000—more than half in the territory. Wyoming lost an estimated 15 percent of its herds—roughly 225,000 cattle.

In 1887, The Denver Republican reported that 70,000 cattle left Texas that year but had been turned back because there was no market. “The national cattle trail is abandoned,” the newspaper reported. “Never again in the history of the United States will great herds of Texas cattle be driven northward through Colorado to Wyoming and Montana.”

A National Cattle Trail “might have been established years ago,” a Pennsylvania cattleman told the New-York Tribune early in 1887, “but was neglected until the country got too thickly settled.”

Railroads had lowered shipping rates, the open-range era of the cattle industry was ending and the great trail drives became part of Western history.

Johnny D. Boggs survived working on cattle drives in Arizona and New Mexico.

Mother of Exiles

by Candy Moulton

Immigration to the West in 1883 transformed the country.

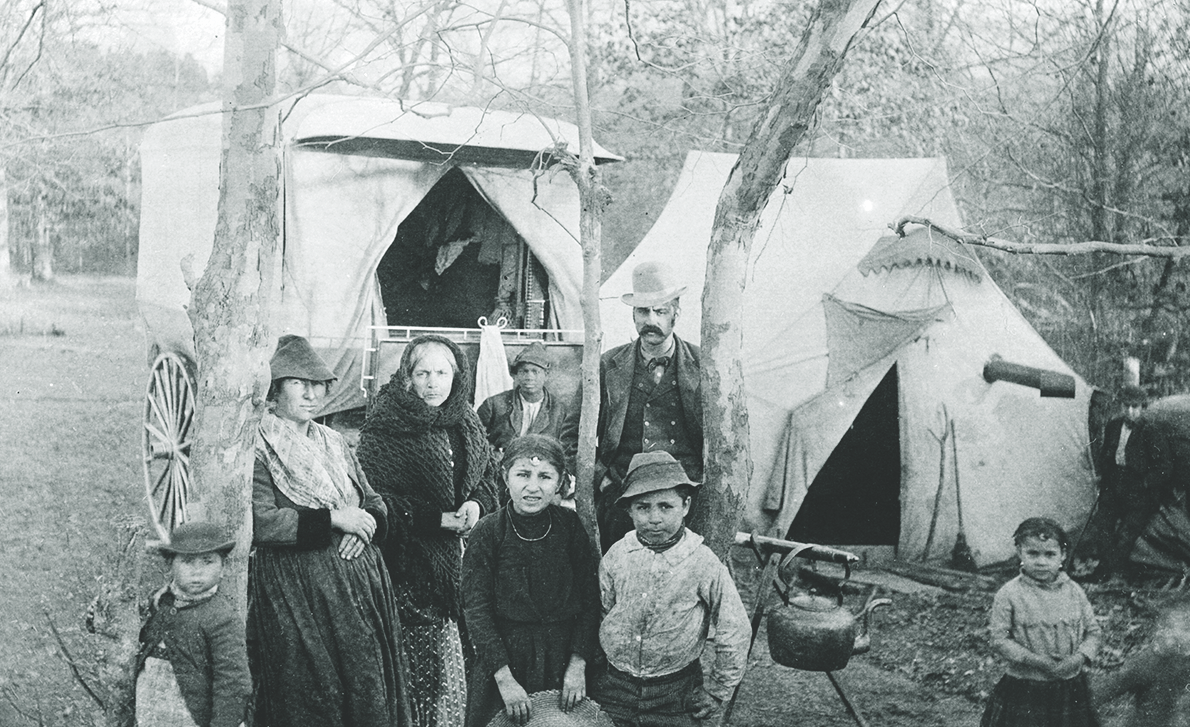

When 1883 writer Taylor Sheridan put a group of German immigrants on a wagon train heading toward Oregon, he drew from the historical record of immigration to America. During the 1880s around 1.5 million Germans came to the United States and the largest number of them arrived in 1882, when about a quarter of a million left their homeland for a new opportunity.

Oregon saw the arrival of the first Volga Germans in 1881, people who had first settled on the Great Plains in central Kansas. Those German migrants left Kansas and found their way to California where they boarded a steamship to travel from San Francisco to Portland. The following year most of them left the Portland area and traveled to Eastern Washington in search of an area where farmland was more plentiful. Some remained in Oregon, founding the village of Blooming.

Germans traveled overland from Nebraska to the Pendleton, Oregon, area in 1882, and while some remained in the Pendleton area, several families kept traveling west to Portland and a new town they established in Albina. A decade later more Germans migrated from the Midwest and Great Plains settling the town of Canby, Oregon.

Immigration by Eastern Europeans to America was not a new phenomenon. Indeed, Germans had been coming to America since the 1600s, with larger numbers arriving in the 1700s as they settled in Pennsylvania and other eastern areas. While living in Pennsylvania, German craftsmen built the first Conestoga wagons. Although these large wagons were never popular with overland travelers due to their massive size, they did see widespread use hauling freight, particularly along the Santa Fe Trail after its establishment in 1821.

One of the better-known Germans who had influence in the American West was John Jacob Astor, who came from his village in Waldorf in 1784 and made a reputation—and a fortune—in the American fur trade. His name remains attached to the area since Astoria, Oregon, was named for him.

The first large colony of Germans to settle in Texas arrived in 1844 and formed the community of New Braunfels. During the 1850s, the first period of peak immigration from Germany to America, nearly a million immigrants made the journey and settled in locations from Pennsylvania to Texas to the Dakotas, Nebraska, Missouri and Colorado.

Like other European immigrants, the Germans and Russian-Germans left their homeland to start over in America in search of better opportunity, religious freedom and to escape political insecurity in their home countries. They brought with them a strong work ethic, the desire to live close to people from their homeland, and foods and beliefs unique to their culture. One other item they brought hidden in their imported bags of winter wheat was a weed that became ubiquitous to the Great Plains and a symbol of the West made popular in later-day films and music: Russian thistle—which we all recognize as tumbling tumbleweeds.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints began sending missionaries to Europe in the late 1830s and during the subsequent two decades encouraged and aided converts to the religion to relocate to the church headquarters in Salt Lake City, eventually spreading throughout Utah and surrounding states. This immigration was heaviest in the 1850s with thousands traveling by ship, train and wagon train from 1850 to 1856. That year the LDS Church launched a new migration method when it began using handcarts for the travelers who literally pushed and pulled their belongings across the plains using small two-wheeled carts that were human-powered. In all around 3,000 Mormon converts from England, Scotland, Ireland and the Scandinavian countries traveled using handcarts.

Swedes began immigrating in the 1860s, with most of them first settling in Illinois before they moved west into the Dakotas and Nebraska. They spread south across Kansas and into Texas and also pushed farther west, finding that their woodworking skills were a great advantage as they built and worked in tie-camps throughout Wyoming after the 1870s and well into the final years of the 19th century.

While some Swedish settlements, particularly in Kansas and Texas, were organized and involved numerous families, the Swedish and Norwegian settlement of the Dakotas was more individualized. Even so, hundreds of Scandinavians found land, built new homes and established themselves in the West, particularly in the period after the 1880s, when the Indian tribes of the region they settled had been forced onto reservations.

Many other nationalities came to the West during the period of 1883 and later, arriving from Ireland, Italy, Belgium, Scotland, the Bohemian region and other countries. All had a similar goal: a better life for themselves and their families.

Immigration to the United States in the 1880s

• In 1880: 6,679,942 immigrants arrived in the U.S.

- 5,751,823 from Europe

- 107,630 from Asia

- 717,285 from Northern America, including Canada

- 90,073 from Latin America, including Mexico

- 6,859 from Oceania

- 2,204 from Africa

• In 1882, 250,000 Germans arrived in the U.S., with over 1.5 million arriving between 1880-90.

• The mass migration of Jews from Russia, Austria-Hungary and Romania to the U.S. began in 1880.

• Entrance into the U.S. was regulated by the Passenger Act of 1882, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first American law to forbid one specific nationality from legally immigrating to the United States.

Candy Moulton is the author of The Mormon Handcart Migration: ‘Tongue Nor Pen Can Never Tell the Story,’ and Roadside History of Nebraska. Her own family immigrated from Belgium, but not until the early years of the 20th century.

Big Jim Courtright

by Erik J. Wright

Fort Worth’s marshal was as notorious as the Hell’s Half-Acre he ruled.

Billy Bob Thornton’s portrayal of Fort Worth Marshal Big Jim Courtright in the hit series 1883 makes for great television, but it is not how things really were. In the show, Courtright polices the bawdy and dangerous red-light district known as “Hell’s Half-Acre,” which was a real place, but even the most violent mining camps in Nevada—some of the toughest to have ever existed—were not as bad as this. However, this is television, and media like this is meant to inspire further interest in the history behind the stories they portray.

So, who was Jim Courtright? Courtright was a native of Illinois who fought for the Union during the Civil War. While little is known about his early years, by the time he ended up in Fort Worth he was known to be working both sides of the law.

Certainly, Courtright was a tough individual. He was a known gambler and gunman with a fearsome reputation, but not the type to walk into a saloon and kill five cowboys in a matter of seconds. Courtright was shrewd enough to understand that the cowboys were good for the local economy even if the “acre,” as it became known, was gaining a disreputable image across the state of Texas. In 1883, the Austin Weekly Statesman called the acre the “Five Points of Fort Worth,” while the following year the Laredo Times noted “[In Hell’s Half-Acre] the devil would find his own and be at home there. Quick to defend its home turf, the Fort Worth Daily Gazette responded to like allegations in 1890. “There is no ‘Hell’s Half-Acre’ here. Fort Worth has no more bad people in proportion than you would find in any prosperous city…” Still, men like Courtright did nothing to enhance the acre’s reputation. Known for operating a protection racket for local businesses including saloons, brothels and gambling dens, Courtright ran afoul of Kansas gunman and gambler Luke Short. Known widely for his killing of Pacific Slope gambler Charlie Storms in Tombstone in 1881, Short had fallen back to Dodge City before coming to Fort Worth.

By 1887, Short was operating the upstairs gambling concessions in the White Elephant Saloon, which sat several blocks north of the acre and thus attracted a more respectable clientele. Unpopular with both city officials for his promotion of Keno games, and down-on-their-luck gamblers like Courtright, Short, known locally as the “king gambler of Fort Worth,” was an easy target. Numerous theories exist as to why the two men clashed, but the likely scenario involves Courtright approaching Short for a cut of the action, thus infuriating Short. Whatever the reason, during a heated conversation between the two on the sidewalk just north of the White Elephant on the night of February 8, 1887, both men drew iron, and Courtright dropped dead with three bullets from Short’s gun.

After the death of Courtright, many of his friends and associates sought revenge, but an effort to lynch Short was foiled. Legal charges against him were ultimately dropped, likely in support of self-defense, as it was widely reported that Courtright drew first.

Law and Order on the Overland Trails

by Erik J. Wright

Each traveler was a marching ordnance department.

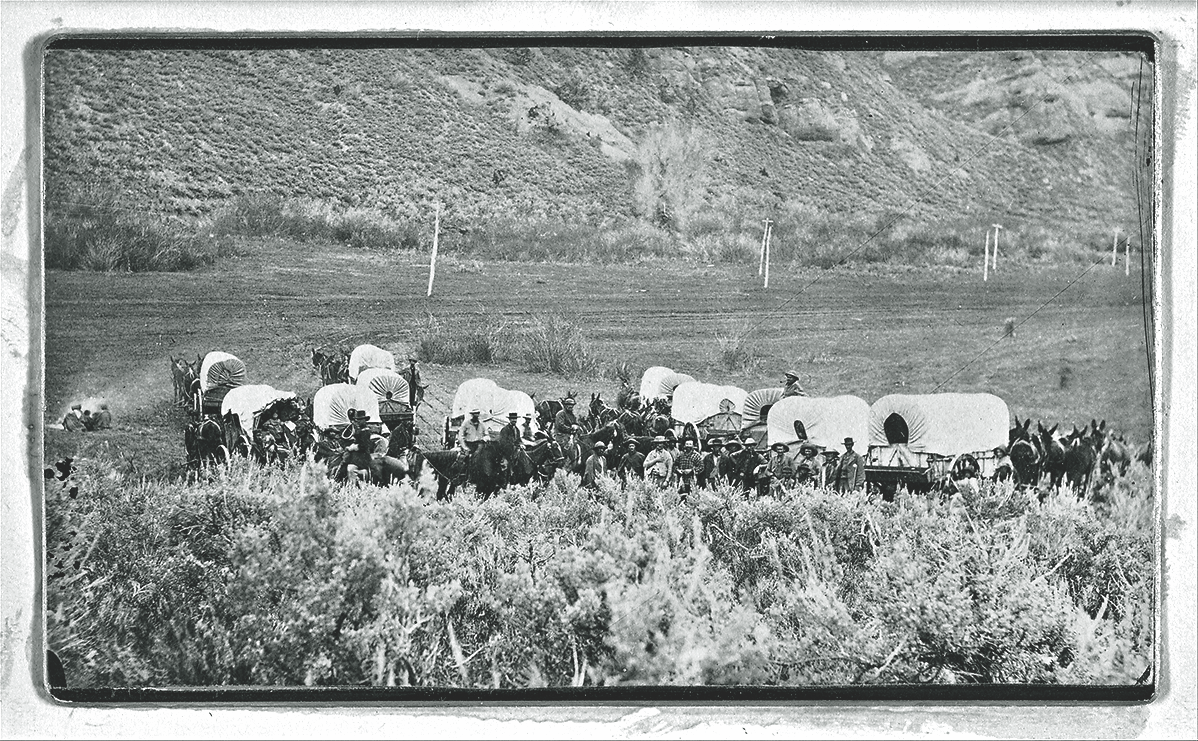

Over the span of about 30 years, an estimated 300,000 emigrants traveled the overland trails to points west in places like California, Oregon and Utah. Many of these intrepid travelers were inexperienced farming families from the East or individuals from overseas with no practical experience with the kinds of dangers that could befall them on the journey ahead. Disease, accidents, Indian depredations and harsh environmental conditions all played into the dangers of Manifest Destiny. The journals and letters of overland trail emigrants often begin with an idyllic and optimistic tone, but that quickly sours once the traveling became arduous as they neared the Rocky Mountains. Adding to the danger was the probability that most of the emigrants had no experience with firearms outside of hunting. As a reaction to the dangers that lay ahead, emigrants often armed themselves heavily.

One contemporary noted the “[emigrants’] fixation with firearms,” while George Gibbs, writing from Fort Kearny in Nebraska observed that “[Each traveler] was a marching ordnance department.” The Missouri Republican printed a letter on June 16, 1869, from someone known simply as “Pawnee,” and in it the writer said, “[A]rms of all kinds must certainly be scarce in the States, after such a drain as the emigrants must have made upon them. Not a man but what has a gun or revolver or two, and one fellow I saw actually had no less than three bowie knives stuck in his belt.”

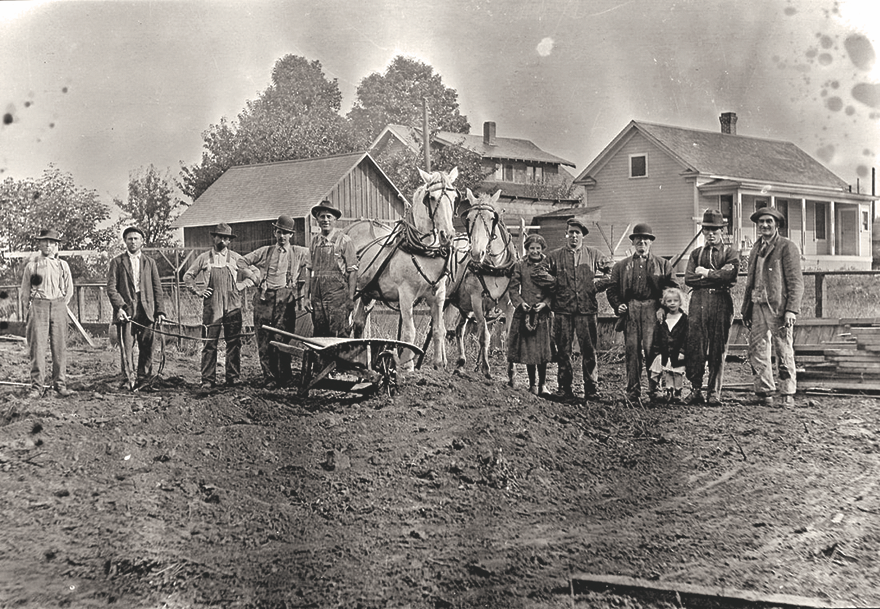

Most of these emigrants traveled in large wagon trains that set out from places like Westport, Missouri. This assured some level of protection, but it was not a guarantee. Official promoters of law and order were only available at the sporadic forts along the trails. Otherwise, the emigrants were on their own. Therefore, a “captain” was selected by popular vote to lead the wagon train like a captain of a ship would oversee his sailors. Overlander Oliver Goldsmith recalled some years later, “Indeed we were prepared for almost any emergency. In our company [wagon trains] were a blacksmith, several carpenters, wagon-makers, millwrights, mechanics of all kinds and men of all professions.”

Despite the usefulness of Goldsmith’s wagon train, some, however, were not so lucky. Early in the overland trail experience, outlaws saw the mass migration as a prime opportunity for exploitation. Pioneer Loren Brown Hastings later wrote, “I look back upon the long, dangerous and precarious emigrant road with a degree of romance and pleasure; but to others it is the graveyard of their friends.”

To combat these fears of impending violence the wagon trains often established an ad hoc legal system. Trial by jury for guilty offenders for offenses like theft, assault and other smaller crimes were dealt with swiftly. Severe crimes like rape and murder were given harsh punishments which were often in the form of banishment from the wagon train. One such example was recalled by Goldsmith who, after a hailstorm on the plains, encountered a lone Irishman approaching his wagon train with nothing but a tea kettle on his head to protect him from the elements. Sometimes, however, those overseeing the judicial proceedings opted for execution. In June 1852, a young man named Lafayette Tate stabbed another member of his party in the back. With the trial under way, Tate protested and requested to be taken back to civilization to stand trial. However, one member of the wagon train recalled, “[H]e had committed murder on the plains; he should be tried on the plains, and if found guilty, should be hung on the plains.”

Erik J. Wright is an associate editor of True West and the assistant editor of The Tombstone Epitaph.

The Pinkertons Find Their Way West

by Mark Boardman

After 1865, the Midwest detective agency became respected and feared across the frontier.

The Pinkerton Detective Agency was bound to join the movement to the West. Like so many, it followed the rails.

Upon founding the organization in 1855, Allan Pinkerton signed contracts with a number of small, Eastern railroads. The original task: prevent employee theft of company property as well as goods slated for shipment. The Pinkertons’ success was noted by other railroad companies in the Midwest.

After its Civil War work protecting President Abraham Lincoln and spying for the Union, the agency turned its focus back to the railroads—but it faced a new challenge. In 1866, Indiana’s Reno Gang started holding up trains, seeking riches from the Adams Express shipments. Adams and the railroads failed to stop the robbers, so they called in the Pinkertons; that the agency was based in nearby Chicago expedited the hire. The Pinkertons, working with local law enforcement, and often relying on dubious methods, helped break the Renos.

Allan Pinkerton took all the credit and spearheaded a national publicity campaign. Railroads farther west took notice; so did state and local governments, which hired the agency to take on outlaw outfits in their areas. The Pinkertons battled the James-Younger Gang and the Wild Bunch, among other gangs. The agency’s reputation grew as it moved to the West Coast. There were failures, such as the 1874 bombing of a Missouri house that killed the half-brother and maimed the mother of Frank and Jesse James. But the bad publicity did little to shake the confidence that the railroad barons and government officials had in the Pinkertons. And the company’s public relations machine cranked out the exaggerated narrative that they were the top crime-fighters in the U.S.

Other industries decided to follow suit. Mining companies wanted greater control over their workers, so they brought in the Pinkertons to fight unions. In the early 1870s, detectives helped crush the Molly Maguires, a violent Irish immigrant group that disrupted operations in the Pennsylvania coal fields. And as mining developed out West, companies hired the Pinkertons for similar jobs.

By the 1890s, the Pinkertons had moved into violent strike-breaking, effectively creating and enforcing their own laws. Many rank-and-file Americans began considering “Pinkerton” another word for thug. But the agency benefactors—especially railroad and mining interests—continued using its detectives well into the 20th century. The Pinkerton Detective Agency covered the nation by following the rails.

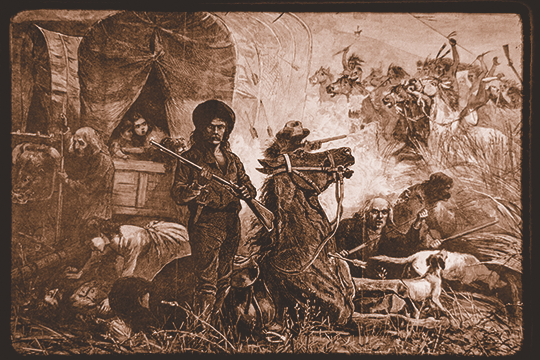

Indians and Wagon Trains

by Mark Boardman

Hollywood exaggerates the danger faced by travelers.

The scene is a familiar one in the Westerns. A wagon train bringing Easterners to a land of hope and opportunity is attacked by Indians. Sometimes, the train is strung out in a long line along the well-traveled trail. In others, the voyagers have settled in for the night when Natives rush the group, seeking to kill the whites and steal their horses and other animals as well as various and sundry items.

If one accepted that as gospel, it appears that every caravan was subject to attack. Well, that’s Hollywood’s take. But it’s an exaggeration.

Yes, there were Indian attacks on wagon trains—but nobody knows how many such fights there were between the 1820s and 1880. For several reasons, it’s likely that they were rare occurrences.

First, the travelers were generally well-armed and prepared to fight as needed. They viewed Indians with suspicion and were normally on their guard. At night, most did circle the wagons to form an impressive fortress (and to keep animals penned inside). Indians were reticent to charge such a barrier, knowing that they would take heavy casualties—even if they eventually won the battle.

And, as more forts were constructed on the trails, Indian bands faced the possibility that soldiers were nearby and could intercede in any attack.

There were exceptions. Sometimes a wagon train would get strung out on the trail, with some wagons lagging far behind. Indians could pick the stragglers off before the other travelers could mobilize a defense. After that, the survivors were much more cautious.

Or the Indians used subterfuge to gain an advantage. In July 1864, a small wagon train—five wagons with 11 people—was on the Oregon Trail, about 120 miles northwest of Fort Laramie, Wyoming Territory. A group of mainly Oglala Sioux Indians approached the group, signaling peaceful intentions. They asked for sugar, tobacco and bread, which they were given. The Indians joined the train as it continued its journey.

More Indians, perhaps totaling 100 warriors, also joined. The travelers stopped to camp for the night, unhitching horses and shifting possessions. While their attention wandered, the Indians attacked. Three members of the train were killed and several others wounded. A number of women were captured and taken away, although most escaped within a few days.

Other wagon trains following the trail learned from that incident and were on guard. Most of them never saw Indians.

But that’s not the Hollywood version.…

Mark Boardman is features editor of True West and editor of The Tombstone Epitaph. He is also a pastor in Indiana.

Blood Brothers

by Stuart Rosebrook

1883 recreates a unique moment in the Civil War.

In 1883’s episode two, Taylor Sheridan recreates an actual moment from the Civil War with Tom Hanks as Union Maj. Gen. George Meade and Tim McGraw as Confederate Capt. James Dutton. In the fictional flashback scene to the Battle of Antietam of September 17, 1862, a Confederate officer (McGraw, above left) staggers to his feet and wanders among the dead bodies (many posed faithfully from Mathew Brady photographs). Then we see General Meade (Hanks, above right) sit down next to the Confederate captain and they commiserate.

In reality, 2nd Lt. George Armstrong Custer was photographed visiting with his captured West Point classmate, Confederate Lt. James B. Washington, on May 6, 1862, several days after the Battle of Williamsburg. In the immediate aftermath of the bloody fight, Custer walked amid the dead and dying and found another fellow West Pointer, 5th N.C. Infantry Capt. John “Gimlet” W. Lea, then carried him to a Union field hospital. Lea survived, and two months later, Custer stood up with his captured, recuperating friend in his wedding to Margaret Durfey.

Swearing in Westerns

by Bob Boze Bell

Is the cursing on the streaming series 1883 accurate?

I think it’s safe to say most of us are more profane than our parents, or, certainly, earlier generations. I know I swear quite freely in conversation with friends and at work—especially at work—and, for some reason, when I am talking out loud to myself. When I am on my daily walks, I talk a blue streak, usually about some dumb thing I did, or said. Sometimes my dog, Uno, looks up at me, like, “Are you alright?”

Some might see this all as liberating and make the argument that today we are freer to express ourselves without judgment or the silly rules of polite society. I half buy that, except for when I was with my kids, ages 6 and 9, on a Salt River Tubing bus and some teenagers in the front of the bus were loudly cussing up a storm with the centerpiece being the F-bomb in all its ridiculous permeations. The bus driver finally told them to “pipe down,” but, of course, that made them even louder and more profane. At that point I didn’t see it as liberating, just coarse and inappropriate.

Courtesy Library of Congress

Which brings us back to the swearing in 1883. I have posted several takes on this cussing phenom down through history and in Westerns of late, and the response has been astounding, with over 180,000 views and over 700 comments.

Let’s see if I can distill down what I heard you say and what I believe to be true: The use of the F-bomb in a Western is off-putting because it sounds too modern and coarse for a cowboy to be using.

Some linguists have postulated that the overuse of the F-bomb as a verb, adjective and everything in between is a by-product of WWII, when “The Greatest Generation” needed extra octane when it came to describing and surviving savage war conditions. Consider the acronym: FUBAR from 1944. If true, and I tend to buy it, then the usage of the word in a Western is not authentic to Old West times.

Here’s a good rule of thumb: if you hear a cowboy use the word Ma’am in a sentence, he will not say swear words of any kind in front of women and children. He just won’t. It is not condoned in his culture, past and present. And, it is not condoned and it will not be tolerated even by the roughest of the breed. Especially by the roughest. Yes, he will swear on the range with other men, perhaps even using the F-bomb, but if a woman shows up, he will clip his lip pronto. This is true today, but it was even more true back then.

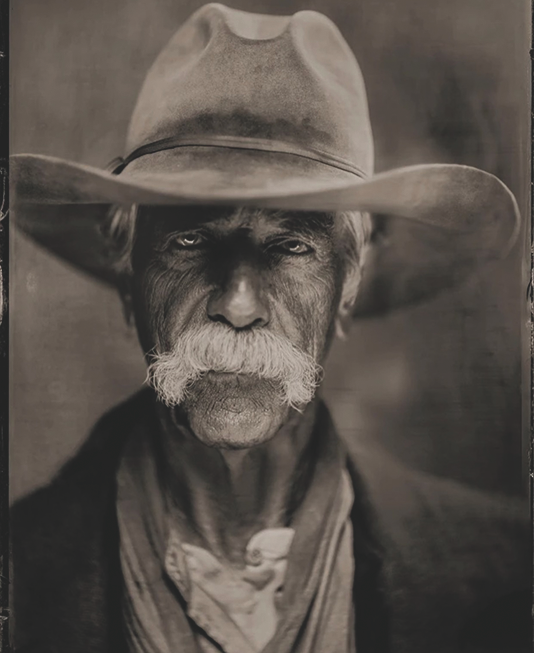

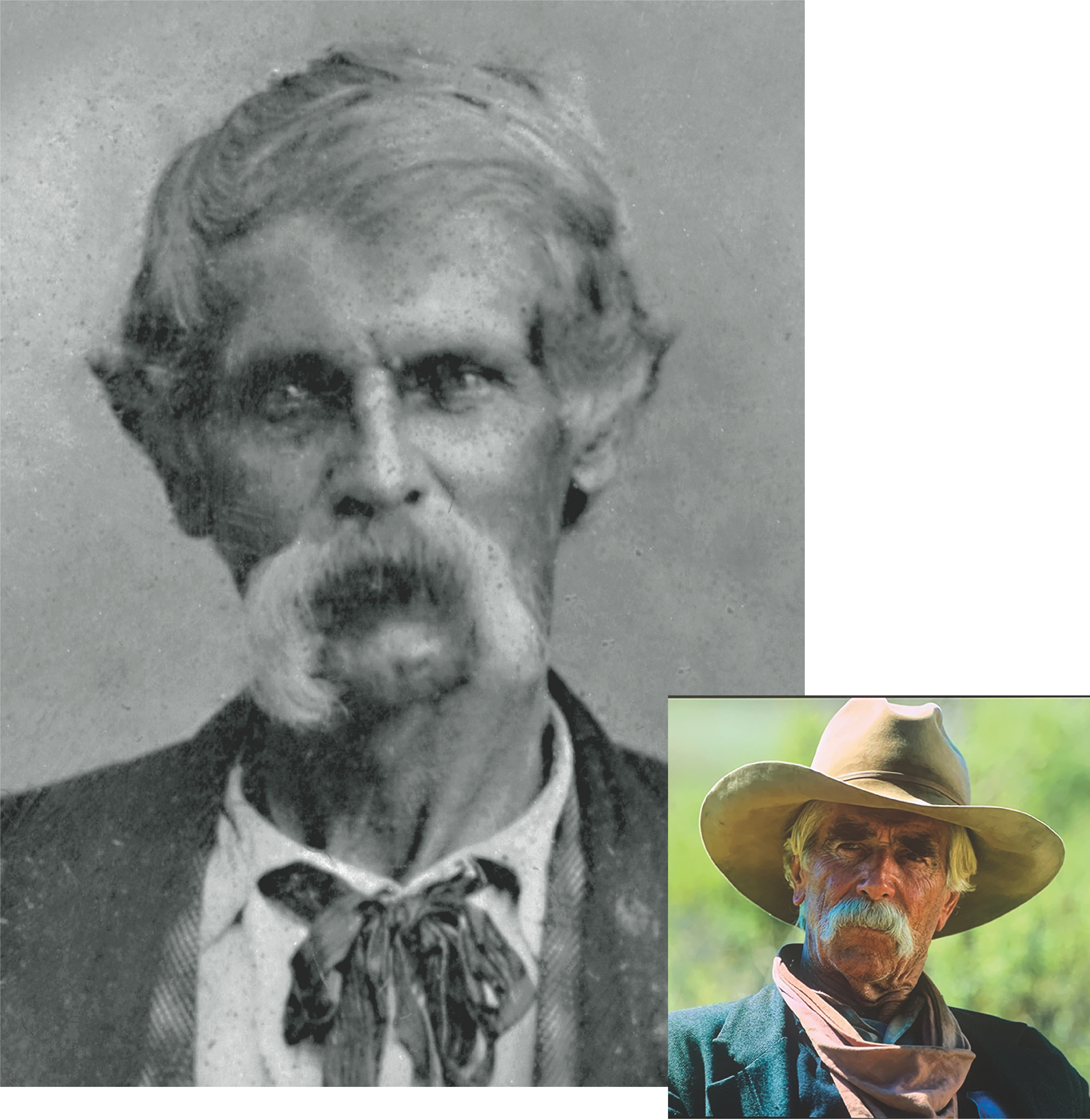

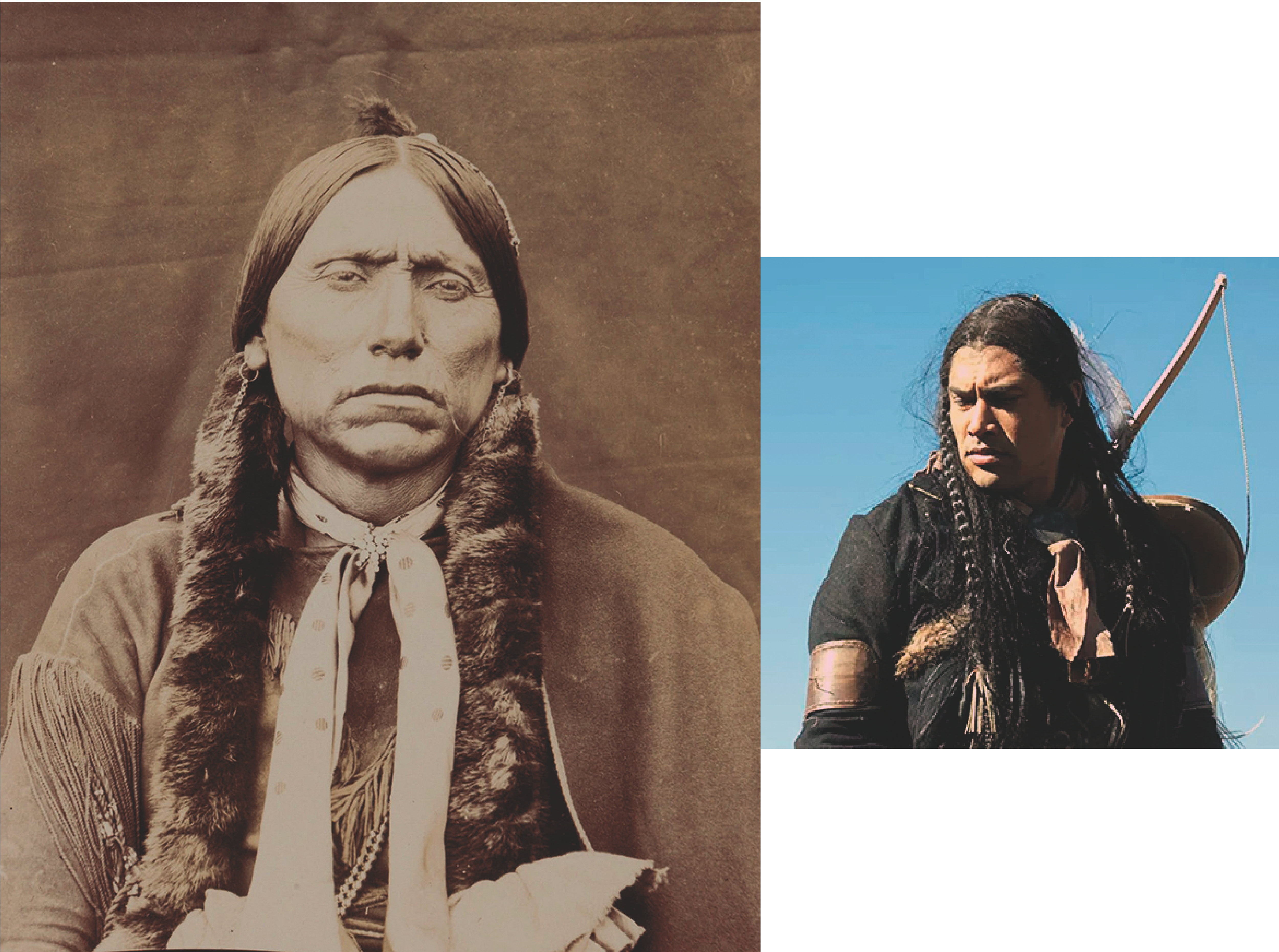

Dead Ringers

by Stuart Rosebrook

The Faces of 1883

Unknown Cowboy, c. 1870s Courtesy Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photographs

Martin Sensmeier as Sam, Comanche warrior