The deadly and dangerous life of the man who invented Wyatt Earp.

Thanks to a 1960s television show starring Gene Barry, Bat Masterson was called a “legend in his own time,” at least in the popular imagination. But the legend actually began long before that, in August 1881, in the boomtown of Gunnison, Colorado. A reporter for the New York Sun was in town looking for a colorful story about the Wild West for his eager readers in the big city. He was expecting to see hourly gunfights in the streets, and having seen none, was disappointed. He asked some of the locals if those wild and woolly escapades were just tall tales, pulling legs attached to tenderfeet. One of the men, Dr. W. S Cockerill, agreed and then said, “There is a man who has killed 26 men and he is only 27 years of age.”

The writer could barely contain his eagerness to hear the rest of the story. With his pad and pencil in hand he anxiously waited for the doctor to say the name of this deadly gunfighter.

“He is W. B. Masterson, of Dodge City, Kansas.” Dr. Cockrell then proceeded to regale the young man with lurid tales of the superhuman acts of the fearless lawman known as Bat Masterson. While the scribe wrote furiously, the doctor finished his tale with a spectacular finale.

The sensational story appeared in the New York Sun and the eastern folk swallowed it hook line and sinker. It might have had a short life except that it was picked up by several Western newspapers, including the Ford County Globe, published in Dodge City. A reporter for the Kansas City Journal just happened to be in Dodge and managed to get an interview with the man who had gunned down 26 men.

Bat was also a practical joker. He managed to answer his questions with the skill of a politician. He dodged, double-talked, evaded and spun his answers. The legend of Bat Masterson had begun, and like all legends, there was a whole lot of reality thrown in.

The real Bat Masterson was a less than perfect creature subject to the same temptations and vices as the other sporting men of his day. He only killed one man, Cpl. Melvin King, on January 24, 1876, in Sweetwater, Texas. Like many, he was a flawed character, but he lived by a code, and he was loyal to his friends.

Bat Out West

Bat’s history in the Old West was every bit as illustrious as that of Wyatt Earp, and in the early 1900s, he was actually more famous than Wyatt. Bat had a bigger story to tell than Wyatt. For example, at the Second Battle of Adobe Walls on the morning of June 28, 1874, the 20-year-old lad was the youngest member of 28 buffalo hunters who held off hundreds of Comanche, Cheyenne and Kiowa warriors. This was the battle during which sharpshooter Billy Dixon, using a Sharps .50-90 caliber rifle, took aim at a party of war chiefs on a bluff about a mile away and fired. More than four seconds later, one of the warriors fell from his horse. Dixon’s shot measured 1,535 yards and quickly became known as the “Shot of the Century.”

Quanah Parker, one of the war chiefs on the bluff decided the white man’s medicine was too strong to continue the fight, and the warriors rode away.

Bat also had been a scout for the Army during the 1874 Red River War and a Western sheriff of renown. He lived and worked in a rough-and-ready environment of gambling and law enforcement. His reputation, however, daunted most troublemakers. He was quiet in demeanor, tough but he was no bully, bluff or blowhard.

Bat was a gamer; in the lexicon of the West, he was “a good man to ride the river with.”

However, in later years, when someone asked him about legends in the West, Bat preferred to talk about his friend Wyatt Earp, whom he greatly admired. When President Teddy Roosevelt suggested that Bat should write his story, he is supposed to have replied, “Mr. President, the real story of the Old West can never be told unless Wyatt Earp will tell what he knows, and Wyatt will not talk.”

Roosevelt’s press aide, the legend maker himself, Stuart Lake, heard this and was thus inspired to seek out Wyatt and write the highly fictionalized 1931 biography of Wyatt that turned him into a legend. Lake even allegedly borrowed many of Bat’s first-person descriptions of lawing, gunfighting and buffalo hunting and attributed them to Wyatt.

Ironically, Bat might have become the legend, had he been inclined to self-promote himself to Lake.

Canadian Born, Western Raised

Bat Masterson was born on November 26, 1853, in Quebec, Canada, and baptized Bartholomiew, which the family shortened to Bart or Bat. He was the second of seven children in the Masterson family. Apparently, he didn’t like the name, so as a young man he chose a new handle, William Barclay.

In 1871 the family moved to Sedgwick County, Kansas, a few miles from the cattle town of Wichita. A year later, after helping the family get settled in, Bat, almost 18 and his older brother, Ed, 19, headed for buffalo country.

The government estimated in 1870 there were 50 million buffalo on the plains and 10 million between Fort Dodge and Camp Supply in the Oklahoma panhandle. Men hunted for sport, buffalo robes and meat to sell to the railroad crews laying track for the Santa Fe and Kansas Pacific. Up until then buffalo were hunted only in the winter, but that changed in 1871, about the time Ed and Bat became hide hunters. The demand for hides was great for machine belting, and the industrial revolution was ramping up. The buffalo, or more correct, the bison, were doomed to near-extinction.

Near today’s Caldwell, where the hunters got their provisions, the two boys found work as skinners and stock tenders and headed into buffalo country. When the hunters signaled for the wagons, the skinners came forward and began the bloody and dirty job of taking the hides. They worked seven days a week. During the hot summer months they had to deal with flies, and when cold weather arrived the flies were gone but carcasses froze quickly. It was during this time Bat and Ed met and became friends with sharpshooter Billy Dixon. In early 1872, Bat also met the man who would become his lifetime friend, Wyatt Earp.

In the summer of 1872, the Masterson brothers hired out for a railroad grading crew contracted by Raymond Ritter. By July the rails had reached Buffalo City, where a townsite was laid out and the town given a new name, Dodge City. Ritter skipped out with their wages, and the boys went back to hide hunting. Soon they were joined by their younger brother Jim, and by fall all three were hunting buffalo.

After the arrival of the Santa Fe Railroad in September 1872, the town of Dodge City quickly grew from a sutler post for hide hunters to a wild, boisterous, bibulous Babylon. The Alhambra Saloon, gambling hall and restaurant was run by Jim “Dog” Kelly and Peter Beatty. Tom Sherman’s dance hall provided such charming specimens of Eve’s flesh as Nell Pool, Nell St. Clair and Lil Thompson, who provided short-term romance for the love-starved hide hunters and soldiers from nearby Fort Dodge. The town had yet to have an organized government, and shootings were a daily occurrence. It was said that during the first year there were 25 killings and twice as many shootings.

Ed Masterson returned to Dodge in February 1873 and hired out at the Alhambra. Jim arrived a few months later. Bat and Jim took jobs hauling buffalo hides from the camps into Dodge.

Like in other raw frontier towns, when the lawlessness got out of hand, a vigilance committee was organized, and like other towns, the group was infiltrated by troublemakers who took control and used it for their own purposes.

Major Richard Dodge, commanding officer at Fort Dodge, upon learning his former cook, now running a restaurant in Dodge, was murdered in cold blood, wired Kansas governor Thomas Osborn and got permission to intervene. He surrounded the town with soldiers and began making arrests. This was a few years before Congress passed the Posse Comitatus Act that forbade federal troops from enforcing domestic policies.

On June 5, 1873, Dodge City held a special election and selected Charlie Bassett as first sheriff of Ford County. The rule of law now prevailed. It didn’t stop the lawlessness, but it was a start.

Being a witness to the mob rule caused Bat to have a strong abhorrence to vigilante violence during his career as a lawman.

About this time Bat learned that Raymond Ritter, his old boss from the railroad grading job, was coming through Dodge. Bat met the train, entered the car, gun in hand, and made Ritter pay the $300 owed him. A curious crowd had gathered to watch and was impressed with his grim determination. Up until that time Bat was not well known, but the word spread quickly, and from then on folks knew he was not a man to trifle with.

That spring Bat went back to hunting buffalo, but the season of 1873 wasn’t as good as the year before, and the hunt of 1874 was even worse. It seemed the extermination of the Kansas herds was imminent. There were still large herds in northwest Texas, but that was the land of the Comanches, Kiowas and Cheyennes, and they would fight to keep their hunting domain. The work would be dangerous, but the profits would be great if they survived. It was a gamble worth taking.

Dodge Rises from the Plains

In July 1874, Gen. Nelson Miles led the Indian Territory Military Expedition to suppress the Comanche, Cheyenne and Kiowa tribes operating in the Texas Panhandle and Indian Territory in what became known as the Red River War. A unit of scouts was hired to guide the main force. The company consisted of 17 frontiersmen and 20 Delaware Indians. In Miles’s words, the frontiersmen were to be “expert riflemen, pioneers, plainsmen; men of courage and intelligence.” Among those selected were Bat Masterson and Billy Dixon. They would be campaigning in the familiar vicinity of Adobe Walls. The campaign was brief but decisive.

By November Bat was back working as a teamster at Camp Supply. The following month the Army established a post on Sweetwater Creek. It was a bitter winter, and a large number of Indians returned to the reservation while others escaped into the Staked Plains, and by spring the campaign was over. Bat resumed hunting buffalo.

The post was named Camp Elliott, adobe buildings were erected nearby, and the small town of Sweetwater was born. Soon the saloons, gamblers and good-time girls began arriving.

Bat was only 21 and was now getting his taste of the “sporting life.” In Sweetwater he would be engaged in his first gunfight.

Because there were no written accounts of the details, there were several versions of the story, but it appeared to be a love triangle between a pretty sporting girl named Mollie Brennan, Army Cpl. Melvin King and Bat Masterson. One version has it that on the night of January 24, 1876, at the Lady Gay Saloon, King opened the ball by firing at Bat but fatally wounding Mollie. The bullet passed through her and hit Bat in the groin. Bat pulled his pistol and put a bullet in King’s heart. All three fell to the floor in a pool of blood. Bat, seriously wounded, was the lone survivor. He would never take the life of another man, but for better or worse, he would forever be branded as a mankiller.

By April, Bat had recovered from his gunshot wound enough to leave Sweetwater and head for Dodge City. The town had changed in the two years he’d been away. Stockyards were being built, and Dodge City’s merchants were looking forward to the cattle drives that were now headed to Dodge on the Western Trail.

There was a lot of political haggling between factions as to whether to make stricter gun laws or run a wide-open town where anything goes. A compromise was reached deciding the north side of the Santa Fe tracks would have a gun ordinance and the south side would cater to the rowdy cowboys and buffalo hunters.

Bat partnered with Ben Springer and opened a large dance hall, saloon and casino on the south side of the tracks and named it the Lone Star. As the name implies it was meant to cater to the Texas drovers. It had everything the cowhands needed except a church. There was a fine bar, gambling room, show room and a dance hall with good-time girls. Upstairs were rooms where the girls slept and earned extra money taking care of the customers’ sexual desires.

In 1876, Wyatt Earp acted as assistant city marshal, and things were relatively peaceful. Troublemakers were more apt to be “buffaloed,” or given a whack on the head with the barrel of a pistol, rather than gunned down. Bat and Jim Masterson also became deputy city marshals. When news of the gold strike reached Dodge in the summer of 1876, Bat resigned his job with the police and took the train to Cheyenne. By this time, the gold rush fever was on the wane, but Cheyenne was booming so he headed for the gambling halls. Bat was on a winning streak and remained there for five weeks before heading back to Dodge.

In July, Ford County Sheriff Charlie Bassett appointed Bat undersheriff. When Bassett’s term expired at the end of 1877, Bat threw his hat in the ring for sheriff of Ford County. On November 6, 1877, he was elected and sworn in the following January. He appointed his former boss, Bassett, as undersheriff, and among his special deputies were Bill Tilghman, Jim Masterson and Wyatt Earp.

Soon after Bat took office, there was an attempted train robbery in the next county and two posses failed to run down the outlaws, led by the notorious Dave Rudabaugh. The Adams Express Company asked Bat for his assistance. He deputized three former buffalo hunters who were familiar with the area where the robbers were headed. Braving freezing temperatures and snow, they rode in hot pursuit. The unsuspecting outlaws were caught without firing a shot, and Bat was hailed in the newspapers for leading the relentless pursuit of the bandits.

Dave Rudabaugh has been mentioned most often in books on Billy the Kid. He was said to be the only man Billy ever feared. Wyatt Earp called him “the most notorious outlaw in the range country.” In a case of “honor among thieves,” Dave testified against his cohorts in the train robbery and was set free. A newspaper wrote, “Rudabaugh was promised immunity if he would ‘squeal,’ therefore he squole.”

The Masterson Brothers

While Bat was getting praise for his deeds as sheriff, his older brother Ed had been appointed assistant marshal by Bat’s nemesis, City Marshal Larry Deger. Mayor Jim Kelley and Deger were on opposite political sides in Dodge City. Fortunately, Ed Masterson was cool, calm, easygoing and genial. He kept a lid on the hot tempers, but sooner or later things were going to boil over.

On November 5, 1877, while trying to break up a fight in the Lone Star Dance Hall, Ed was wounded. He survived and was hailed in the papers for breaking up a gunfight that had no fatalities. As a result, the city council fired Deger and appointed Ed city marshal. Now, 25-year-old Ed was city marshal, and his 24-year-old brother Bat was county sheriff.

Late in the evening of April 9, 1878, at the Lady Gay, Ed and his deputy Nat Haywood spotted a small group of Texas cowboys drinking with their trail boss Alf Walker. One of them, Jack Wagner, roaring drunk and disorderly, was packing his pistol. Ed approached him and said he needed to check his weapon. Wagner quietly handed his pistol to the marshal who handed it to Walker and asked him to give it to the bartender. Ed and his deputy then left the bar and were standing in the street talking when suddenly the door opened, and Walker and Wagner were walking toward them. Ed noticed Wagner was packing a pistol. He walked up to Wagner and made a move to disable the cowboy, and the two started to grapple. The deputy rushed to help but found himself staring into the muzzle of Walker’s pistol. Haywood reached for his pistol and Walker pulled the trigger, but it misfired.

Meanwhile, Wagner managed to get off a shot, hitting Ed in the abdomen. As Masterson was going down, he fired a fatal bullet into Wagner. Walker turned his pistol toward Masterson, but the mortally wounded marshal got off three more rounds, all of them hitting Walker. One of them was in a lung. He did not die from his injuries, but Wyatt said he died of pneumonia later from the lung wound.

Ed had taken to his room but died 40 minutes later. Despite the stories told by newspapers and magazines for years afterwards, Bat did not go on a rampage and gun down seven men, or even two. There are no accounts of Bat at the fight, although afterwards he did arrest the other cowboys and haul them off to jail.

A local newspaper said this about Ed Masterson: Everyone in the City knew Ed Masterson and liked him. They liked him as a boy, they liked him as a man, and they liked him as an officer. Never before was a greater honor bestowed in Dodge, either to the living or the dead.

The Dora Hand Affair

Beautiful and talented Dora Hand was quite a fascinating woman. She sang in the honkytonks at night and in the church on Sundays. She was accepted by both upper crust society and the town rowdies. Dora, who sometimes went by the stage name of Fannie Keenan, was the featured performer at several Dodge City nightspots. Mayor James “Dog” Kelley served almost like a manager for Miss Hand. He allowed Dora and another entertainer, Fannie Garretson, to sleep in his cottage while he was getting medical treatment at Fort Dodge.

James “Spike” Kenedy was a Texas cowboy from Tascosa. His wealthy father, hoping it would help his reckless son grow up rich, gave him a ranch, fully stocked. Spike considered himself privileged and above the law in Kansas. After he was arrested in separate incidents by Wyatt Earp and Charlie Bassett, he went to the Alhambra and complained to Mayor Jim Kelley, who told him to behave or things would get worse for him. The kid lost his temper and attacked the mayor, who proceeded to give him a good whipping and threw him out in the street. Kenedy sulked about it for a few weeks, then decided to get even.

About 4:30 on the morning of October 4, 1878, Kenedy rode by the mayor’s house and fired four shots through the walls. Unfortunately, one of the bullets struck Miss Hand, who died instantly. The entire town turned out for Dora Hand’s funeral.

Kenedy headed for Texas but was run down, shot and captured by a posse that included Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson and Bill Tilghman. He’d been shot in the arm with a Sharps .50 caliber buffalo gun that shattered it. He expressed remorse upon learning he’d killed Miss Hand.

Despite his confession to the officers, Kenedy was released for lack of sufficient incriminating evidence (although there is some evidence Spike’s father may have bribed the judge). He went back to Tascosa. He never fully recovered from his wounds and lived only a year or two.

The capture of Jim Kenedy turned out to be the only time as sheriff of Ford County that Bat fired his weapon.

Following the capture of Kenedy, campfire tales of the “Shooting Sheriff of Ford County,” and “The lawman who is filling up Boot Hill,” spread far and wide. The stories grew larger with each telling.

Bat the Marshal

In January 1879, Bat was appointed a deputy U.S. marshal. This gave him authority to cross county and state lines in pursuit of perpetrators of federal crimes.

Meantime, a fabulous silver discovery at Leadville launched a rush to the area. Both the Santa Fe and the Denver & Rio Grande railroads had their eye on the Royal Gorge, a narrow steep-walled canyon that followed the Arkansas River up to Leadville. Hauling the ore down to Colorado Springs was slow and costly, and a railroad would be worth a fortune. Both lines were determined to get the right-of-way. Whichever company controlled the Royal Gorge would have the only path to the riches at Leadville. The leaders in what became known as the Royal Gorge War were General W. J. Palmer of the D&RG and W. B. Strong of the Santa Fe. Both lines began hiring enlisting men willing to take up arms.

The Santa Fe prevailed upon Deputy U.S. Marshal Bat Masterson to raise an army at Dodge City, and he had no trouble finding men in the rough-and-tumble town of Dodge City. Among the men who joined Bat’s army were Texas gunman Ben Thompson and former dentist-turned-gambler Doc Holliday.

It would be a two-pronged war; on one side were the mercenaries hired by both railroads and the other side was in the courtroom. The Santa Fe legally had the rights to the gorge, but the case was pending in the hands of the U.S. Supreme Court. The D&RG claimed the Santa Fe had violated the lease.

On April 21, the Supreme Court ruled the D&RG had a prior right but not an exclusive one. That seemed to settle the situation, so Bat took his army and returned to Dodge.

Two months later Bat got a letter to bring his 65 mercenaries back to the Royal Gorge and within an hour they were riding the rails to Colorado. Bat and his men were charged with guarding the roundhouse and the railroad station at Pueblo.

On the morning of June 11, General Palmer ordered the sheriffs in every county, backed by D&RG mercenaries on the line, to take the stations occupied by the Santa Fe Railway’s hired guns. By noon they had taken them all, except Pueblo. The roundhouse was the Santa Fe’s last bastion. Bat’s army had fiercely resisted. Palmer’s men decided to take the cannon from the armory, but Bat had beaten them to it and the gun was aimed right at them.

A parley was called, the roundhouse was surrounded, and Bat was convinced it was useless to continue. To continue the fight would only cause unnecessary casualties on both sides, and he surrendered the roundhouse.

In February 1880, a compromise was reached by both sides: The D&RG agreed not to build a line to El Paso, and the Santa Fe agreed not to build one to Denver or Leadville. Instead, the Santa Fe would lay tracks south through Raton Pass and on to Albuquerque.

Bat ran for reelection in the fall of 1879, and his exemplary record as sheriff should have guaranteed a victory, but his political opponents ran a nasty smear campaign, and he wasn’t politically savvy enough to thwart their lies and innuendo. He figured he would win on his record, but he was wrong. He also resigned his position as deputy U.S. marshal.

Bat’s fallback plan was to become a gambler. He already had plenty of experience and success. He headed for Leadville. The boomtown was rich, the casinos were thriving, and he did very well. He remained there for a few months, then headed for Kansas City where he also prospered.

Tombstone

In early 1881, he received word from Wyatt Earp in Tombstone telling him that serious trouble was looming, and he needed help. Wyatt and Virgil were wearing badges, and Morgan was working as a shotgun messenger. Bat was always a man who stood by his friends, and on February 8, he headed for Tombstone.

Bat’s stay in Tombstone was brief but not without some action. He took a job making good money as a faro dealer at the Oriental. On February 25, two of his old friends from Dodge, Luke Short and Charlie Storms, got into a scrap. Bat separated the two and escorted Storms to his room to sleep it off. Then he returned to find Luke standing on the sidewalk in front of the saloon. He was trying to calm him when Storms suddenly reapeared. He grabbed Short by the arm and pulled him out into the street, at the same time pulling his pistol.

Meantime, Short pulled his pistol and shot Storms in the heart. Storms was dead before he hit the ground.

Bat, chief witness for the defense, testified on Short’s behalf and no charges were filed.

A few weeks later, on March 15, 1881, the Benson stage, carrying several thousand dollars in silver bullion was fired upon by four masked men. Riding shotgun that fateful night was Bob Paul. The driver Bud Philpot was shot and killed. Paul grabbed the reins and the stage sped away in a hail of bullets. Another shot entered the back of the stage, fatally wounding a passenger, Peter Roerig.

When word of the robbery reached Tombstone, a posse that included Wyatt, Virgil and Morgan Earp, along with Bat Masterson, Bob Paul and Sheriff Johnny Behan was formed and went out to pick up the bandits’ trail. They tracked one of the outlaws, Luther King, to a ranch where he was captured without incident. The frightened prisoner identified his accomplices as Bill Leonard, Jim Crane and Harry Head.

Most of the posse continued pursuing the stage robbers while Johnny Behan escorted the prisoner back to Tombstone. The posse kept up relentless pursuit for more than two weeks, covering hundreds of miles and enduring great hardship before finally giving up the chase. At one point, Behan was supposed to bring fresh horses for the posse but failed to show up with remounts. Bob Paul’s horse died while Wyatt’s and Bat’s mounts played out. Bat and Wyatt wound up having to walk some 18 miles back to Tombstone.

Soon after Bat returned to Tombstone, a telegram from Dodge City arrived saying his brother Jim was in danger and needed Bat’s help. The unsigned message said, “Updegraff and Peacock are going to kill Jim.”

Back to Dodge

When Dog Kelley lost the mayoral election, Jim Masterson was dismissed as city marshal. Earlier, he’d gone into a partnership with A. J. Peacock of the Lady Gay Saloon. Al Updegraff, Peacock’s brother-in-law, was a bartender in the establishment. Jim believed he was dishonest and tried to get him fired, but Peacock refused. The two argued openly. Soon their fighting became the talk of the town.

Bat set out immediately for Dodge.

At the time Bat and Jim were not in contact, as there had been a disagreement between the two, but Bat was duty bound to look out for his younger brother. Upon reaching the train station in Dodge around noon, he’d jumped off before it came to a stop, and it might have saved his life.

He saw Peacock and Updegraff walking toward him but then turned and ran. Thus began what would be called The Battle of the Plaza. Nobody knows who fired first, but bullets were flying. Then shots began coming from some of Bat’s friends in a Front Street saloon. Updegraff went down with a bullet in his chest.

Bat was placed under arrest. He was charged with “unlawfully, feloniously, discharging a pistol on the streets of said city.” He pleaded guilty and was fined eight dollars.

Updegraff survived and wrote a statement for the anti-Masterson Ford County Globe claiming the Masterson brothers made an unprovoked attack on him.

Bat and Jim didn’t dignify the statement with a reply. That evening they left Dodge.

A New Career

Bat’s love for prizefighting began early. Although he wasn’t a pugilist himself, he was a boxing fan. In February 1882, he was in Mississippi where he witnessed a fight between American heavyweight champion Paddy Ryan and a young upstart from Boston named John L. Sullivan. Among the other spectators at the fight were Frank and Jesse James.

In the ninth round John L. landed a right-hand punch that decked the champ. According to boxing legend it was the first knockout in boxing history and ushered in a new era in heavyweight boxing with Sullivan as the bare-knuckle heavyweight champion. Right up to his death, Bat was a witness to nearly every important heavyweight bout.

Bat’s biographer, Bob DeArment, adds, “Bat did everything in the boxing business except box himself. He managed fighters, acted as referee and timekeeper in many bouts, and promoted. He did get involved in several unofficial fistfights. Bat was very, very knowledgeable when it came to boxing. Except for one thing–he never bet smart. He’d go for underdogs every time, and he’d lose money hand over fist. He knew better…he just didn’t bet that way.”

After the fight Bat headed west again, this time stopping in the new town of Trinidad, Colorado, near Raton Pass. The town was booming, and Bat met many of his sporting friends from Dodge. His brother Jim was working as a deputy sheriff. In April a new mayor was elected and at his first city council meeting Mayor John Conkie named Bat as city marshal. Trinidad was unusually peaceful his first month as marshal,. In early May his old friend Wyatt Earp showed up. He had left Arizona after leading his vengeance posse following the wounding of his brother Virgil and the murder of his brother Morgan in Tombstone. They had killed three of the suspected assassins, and now the Territory of Arizona had a murder warrant out on him and Doc Holliday. Doc had been arrested in Denver by a man named Perry Mallan, who claimed to be an officer from Arizona, and was waiting to be extradited to Arizona. Bat didn’t particularly care for Doc, but he was a friend of Wyatt’s. He knew that if Wyatt or Doc were extradited, there was no way they would live long enough to stand trial.

First, Bat needed to prove that Mallan was not telling the truth and to catch him in a lie. Further investigation found that Mallan was not an officer but a petty swindler and a con man.

The extradition failed after Bat met with Colorado Governor Frederick Pitkin and persuaded him to not sign the extradition papers. Earlier, Bat had asked Pueblo City Marshal Jamison to charge Doc with running a bunco game in that city and bilking a sucker out of one 150 dollars. The marshal arrived in Denver, picked up Bat and Doc and boarded the train for Pueblo. Bat continued on to Trinidad. Doc managed to stall his court date, and when he died at Glenwood Springs in 1887, he was still under bond for Bat’s imaginative scheme five years earlier.

Bat’s tenure as Trinidad’s town marshal abruptly ended in April 1883, probably due to his running a successful faro bank at the same time. He and all the other candidates of the Citizens Party were trounced by the candidates on the Democratic side. However, his brother Jim was appointed a city policeman. By the time the new group was sworn in Bat had moved on. Although he didn’t care if he ever saw Dodge City again, events occurred that called him back. Once again, a friend needed help.

Back to Dodge

What became known as the “Dodge City War” began when Luke Short returned in April 1881 and went to work at the Long Branch Saloon. Two years later he bought Chalk Beeson’s share of the place. In March 1883, his partner, W. H. Harris, was nominated to run for mayor against the “law and order” candidate, Larry Deger, who was backed by the former mayor who also happened to own the Alamo Saloon, the main competitor of the Long Branch. Deger won and the new politicos immediately passed two ordinances aimed against prostitution and vagrancy. These laws were nothing new in the Kansas cowtowns except they were only enforced against the Long Branch and Luke Short.

Three of Short’s prostitutes were arrested, and when he went down to try to straighten things out, he and a local policeman exchanged gunfire. Neither was hurt in the event, but Short and three other gamblers were arrested, taken to the train station and told to get the hell out of Dodge. Short went to Kansas City where he met with former Ford County Sheriff Charlie Bassett. He then wired Bat Masterson in Denver and asked for help. Bat headed for Silverton where he met with Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday. Thus marked the beginning of the bloodless conflict known as the Dodge City War.

Thanks to intervention on the part of the Kansas governor, Short was told he could return to Dodge and have 10 days to close out his business. Not trusting the law in Dodge City, he demanded an escort. A group of some of the West’s most noted gunmen including Masterson, Earp, Bassett, Neil Brown, Bill Harris, Frank McClean, Bill Petillon, Rowdy Joe Lowe and “Shotgun” John Collins decided to get the hell into Dodge to help their old friend. Interestingly, the man whose name got more ink in the press as the deadliest of them all was none other than Doc Holliday.

It looked like a bloody gunfight was eminent, but the presence of such famous gunmen being intimidating was an understatement. The “Dodge City War” was more about telegrams, rumors and the press than about actual bloodletting.

In the end, economics prevailed. Mayor Deger’s action would ruin the cattle business. Pressure came from the Santa Fe Railroad and Kansas Governor George Glick. The two sides met in a dance hall on June 9th and settled their differences. The dance halls and saloons were reopened. After the photo was taken, Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp boarded a westbound train and headed for Colorado.

Apparently, Doc was already back in Colorado and therefore wasn’t present for the famous photograph.

The Long Branch reopened, but Short sold out that November and moved to Texas.

The Gambler’s Road

During the 1880s Bat was constantly on the move, following the gambling circuit and making good money on the green cloth. He did some police work at times, but all were short-term gigs. He was always involving in the boxing world, and in 1885 he refereed a match between the Colorado heavyweight champion John Clow, a challenger, and a prizefighter named Hands. Since boxing was illegal in Colorado the fight had to be moved across the border to Rawlings, Wyoming. Clow knocked his opponent out in the sixth round. Bat was now making connections in the sporting world that would help him later. During that time he met the future president Theodore Roosevelt. Although their backgrounds were quite different, the two instantly hit it off. Their paths would cross again in the near future.

Luke Short, the diminutive, but deadly gambler was challenged again, this time by the notorious Jim Courtright in Fort Worth. “Longhair Jim” was running a detective agency and providing a “protective racket” to local gambling houses. Short informed him he could provide his own service, and Courtright came gunning for him. They both drew their pistols at the same time, but Short was faster. By the time Courtright fell dead on the floor, Short had put five bullets in him. Luke Short proved again that he was no man to trifle with. Short was arrested and locked up to await a hearing,

Courtright’s friends were organizing a lynch mob, so Bat requested that the sheriff let him spend the night in Short’s cell. Bat arrived packing two pistols and two more for Luke. The mob wisely decided to let justice take its course.

That was Luke Short’s next to last gunfight. While he was severly wounded in a gunfight in 1890, Short died in 1893, in bed, with his boots off.

There has been little written about Bat’s love life. There’s no doubt he had a string of short-term love affairs as he was quite handsome, fun-loving and intelligent. Most if not all the women he cavorted with were the good-time gals of the saloons and brothels. He never said or wrote about any particular one. He never seemed to spend time with one for long. The 1880 census reported him living with a 19-year-old concubine named Annie Ladue in Dodge City.

Bat did eventually marry. When he was 38 years old, he wed blonde song-and-dance performer Emma Moulton. His younger brother Tom later said they tied the knot on November 21, 1891, in Denver, however, there are no records to verify that. There are other reports that they had begun living together in the early 1880s. If that’s the case, the relationship would have undergone a strain because in 1886 Bat had a scandalous affair in Denver with a married woman named Nellie McMahon. She and her husband, Lou Spenser, were both performers. While Mr. Spenser acted to an applauding audience, his spouse Nellie and Bat were publicly displaying their affections for each other in the wings of the theater. It’s not clear how long this torrid affair had been going on, but Mr. Spenser saw them from the stage. Later, he told a reporter from the Rocky Mountain News that Nellie filed for divorce and she and Bat eloped to Dodge City. The affair did create a lot of attention in Denver.

A Dodge newspaper noted his arrival but doesn’t mention anything about a beautiful woman accompanying him.

Home in Colorado

Bat finally decided it was time to settle down. He’d accumulated quite a bit of money on the gambling circuit, and he purchased a landmark theater and gambling casino in Denver. The business thrived until a group of moral reformists decided that Denver needed to close down their casinos and brothels and the Palace was in their cross hairs. Bat decided it was time to sell out and move on. In 1891 a mining bonanza was underway in Creede.

In no time at all, Creede grew from a few shacks to 10,000 and at its peak population numbered an estimated 30,000 gold-seekers. Bat was hired to maintain order in the popular Denver Exchange. It was open 24 hours a day, and he was busy keeping things running smoothly. Among the notorious denizens of Creede was bunco artist, Jefferson “Soapy” Smith. He and Bat were old friends, so the Denver Exchange didn’t have to worry about him causing any problems. Bat’s straight, no-nonsense reputation preceded him to Creede, and that made his job much easier.

A Chicago reporter covering the boomtown wrote about Masterson: “He is quiet in demeanor and sober in habit. There is no blow or bluff or bullyism about him. He attends strictly to business.” The reporter also credited Bat with being the chief force for peace in the camp.

Probably the most noteworthy incident in Creede occurred on the afternoon of July 8, 1892, when a rowdy named Ed O’Kelly entered the tent saloon owned by Bob Ford, the man who killed Jesse James. O’Kelly was packing a shotgun. “Hello Bob,” he said and when Ford turned to face him, he cut loose with both barrels. O’Kelly earned for himself the dubious fame as “the man who killed the man who killed Jesse James.”

Bat and Emma decided to return to Denver for one more round in the Mile High City’s sporting world.

Over the next few years Bat worked in boxing circles from Denver. In the world of boxing, fortunes were won and lost in a day. Bat made the mistake of placing too much faith in friends who ended up betraying him. Bitterly, he decided it was time to get into a new line of work.

Inventing Wyatt Earp

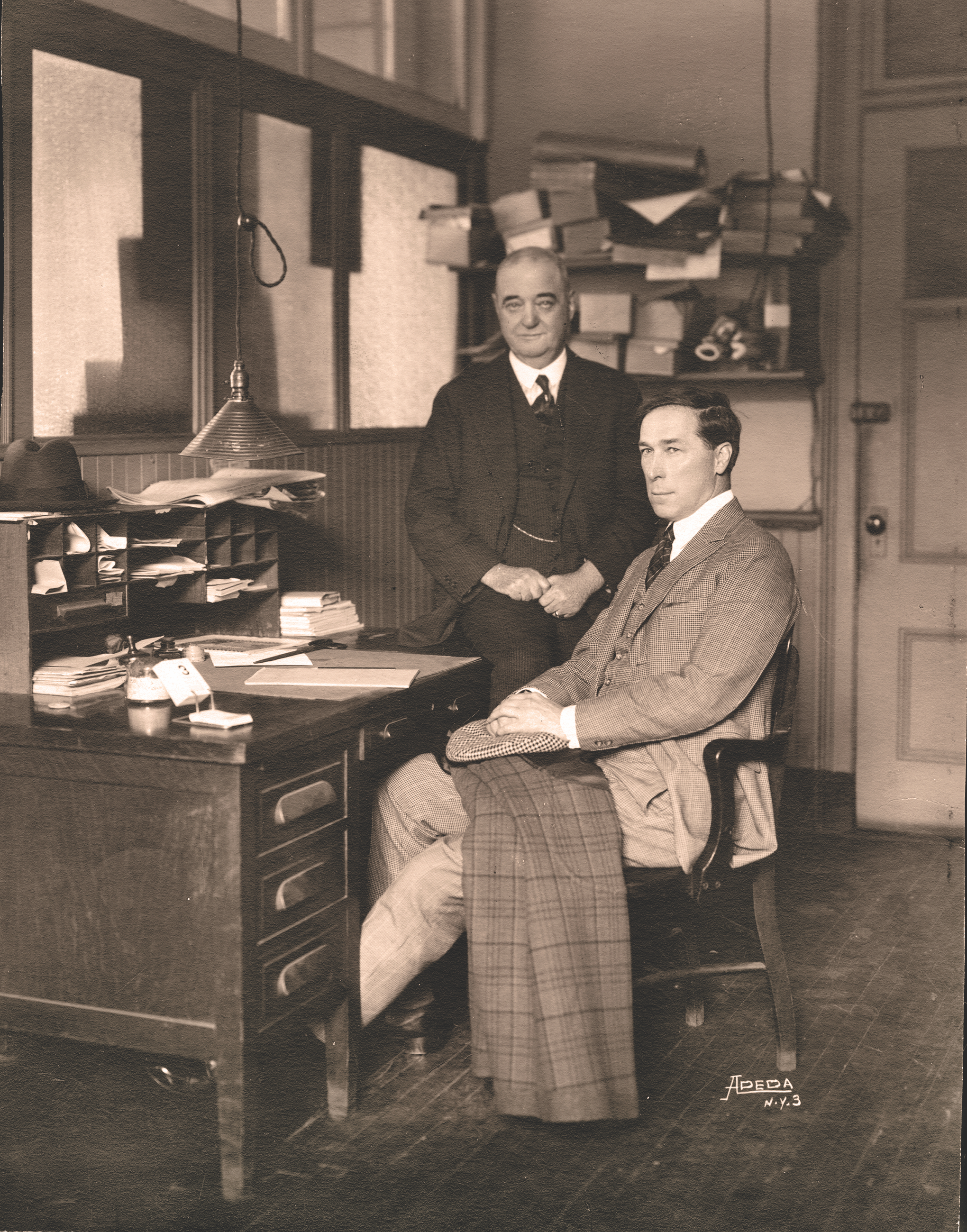

In early 1903, Alfred Henry Lewis, managing editor of the New York Morning Telegraph, was familiar with Bat’s career and asked if he’d come to work as a reporter. At the age of 50, Bat jumped at the chance to do something different. He turned out to be a perfect fit for the popular newspaper. In 1901, his old friend Teddy Roosevelt became President, and after being reelected in 1904, he appointed Bat deputy U.S. marshal for the southern district of New York. Bat often visited the White House as the president’s guest.

Lewis was also editing the magazine Human Life, and in 1907 Bat was asked to write stories about the famous gunfighters he had known. He cranked out stories on Ben Thompson, Luke Short, Doc Holliday, Wyatt Earp, Bill Tilghman and even Buffalo Bill Cody. In all these stories he modestly played down his own role. Lewis took it upon himself to write one about Bat Masterson.

Bat’s column appeared in the Telegraph three times a week. Oftentimes he lambasted the shady side of sports and included crooked boxers, promoters, fixed matches. He once wrote: “A sportswriter who is not willing to stand by his honest judgment…ought to chuck his job and try something else.”

Bat made enemies, just like he did in Dodge and Denver, but he also made a lot of friends. He acquired a wide assortment of friends ranging from panhandlers on the streets of New York to presidents. Among his many friends and admirers was a young reporter named Damon Runyon.

A few years later, Runyon received national fame for his short stories of Broadway’s colorful denizens. One was about a gunslinging, gambling man from Colorado named Sky Masterson. The stories later became Guys and Dolls, first a Broadway musical, then a movie. In the latter, Masterson was played by Marlon Brando. Bat would have liked that.

Bat became good friends with actor William S. Hart, who was a great admirer. Hart was asked to write a short essay on Bat. It was wonderfully written on stationary from the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. Hart didn’t know it, but just a few days later his essay served as the perfect eulogy for his hero.

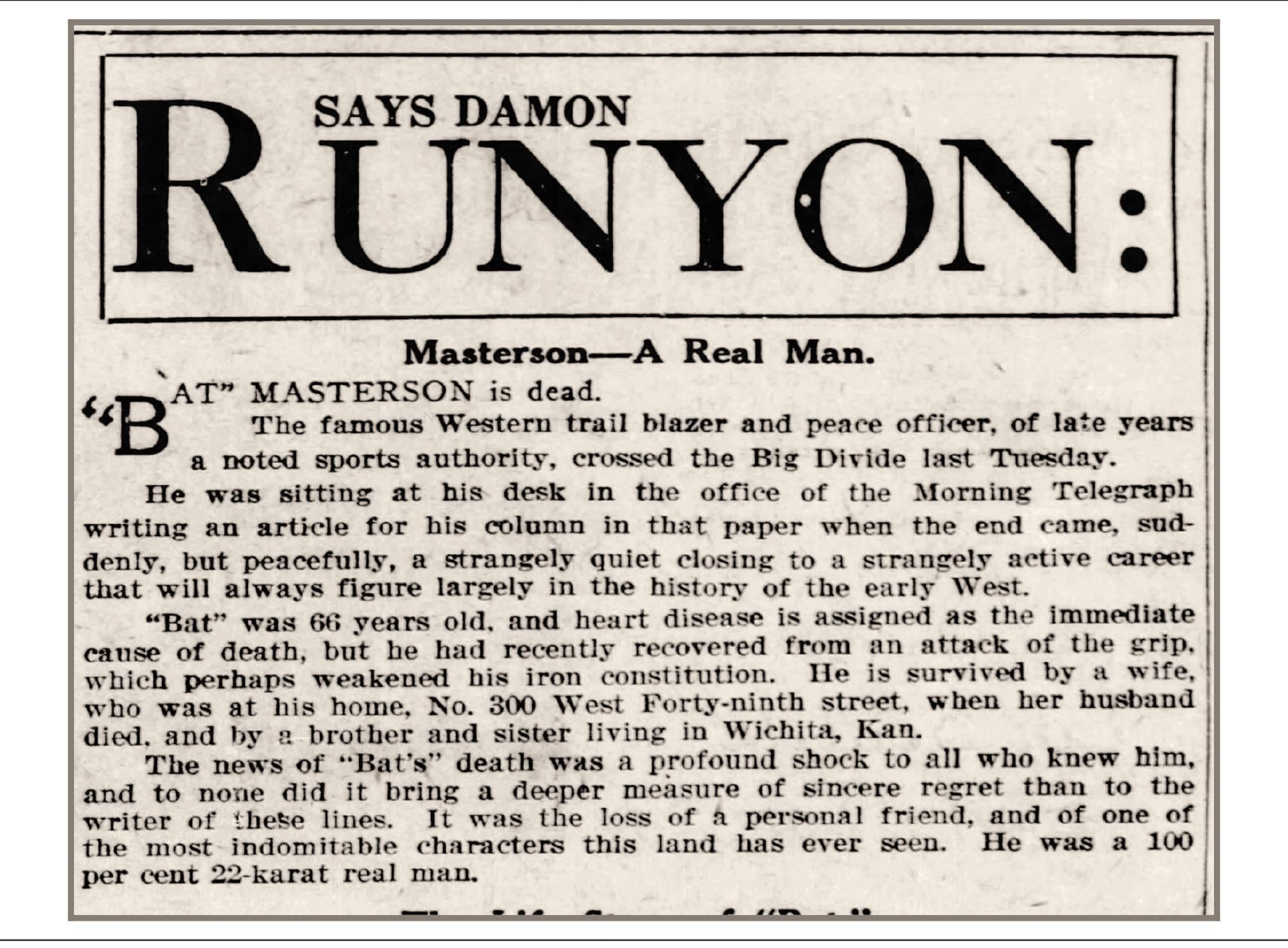

On October 25, 1921, a few days short of his 68th birthday, Bat was at his desk, working on his column. He’d been battling a cold, but he was scratching out the words, on paper with pen and ink. A member of the staff looked in his office to see how he was feeling and Bat was slumped in his chair. The old warrior was dead. It might even be said that he died with his boots on. Bat would have liked that too.

Marshall Trimble is an award-winning author, historian, entertainer and retired professor of history. He has been True West’s “Ask the Marshall” columnist for over two decades.