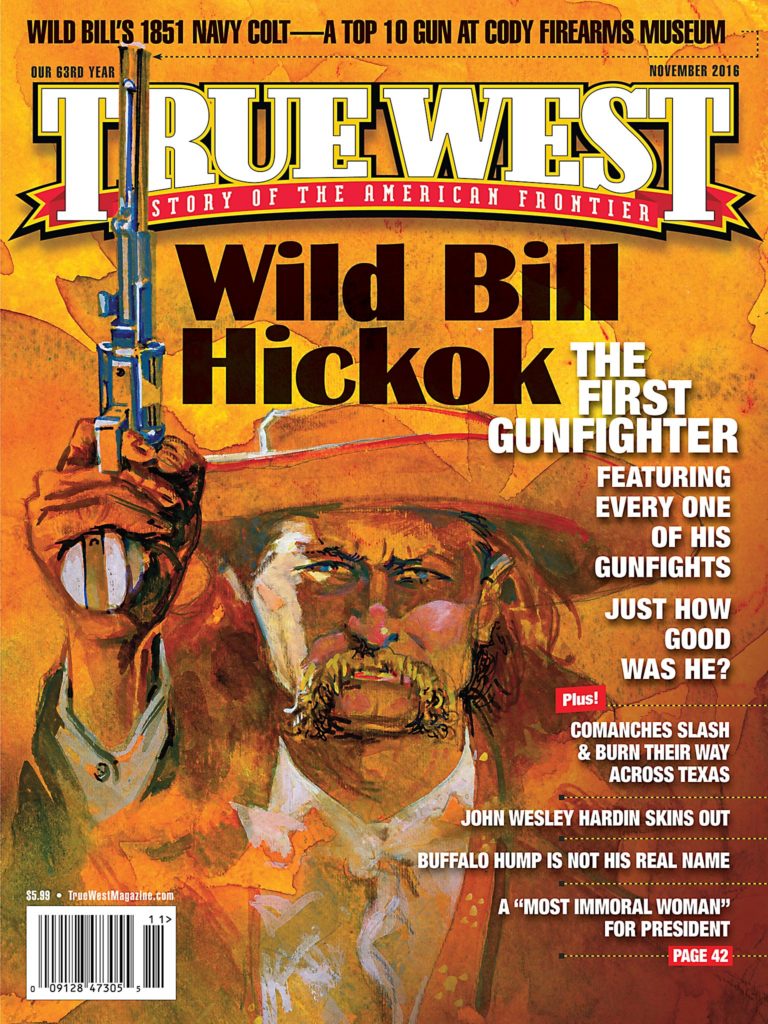

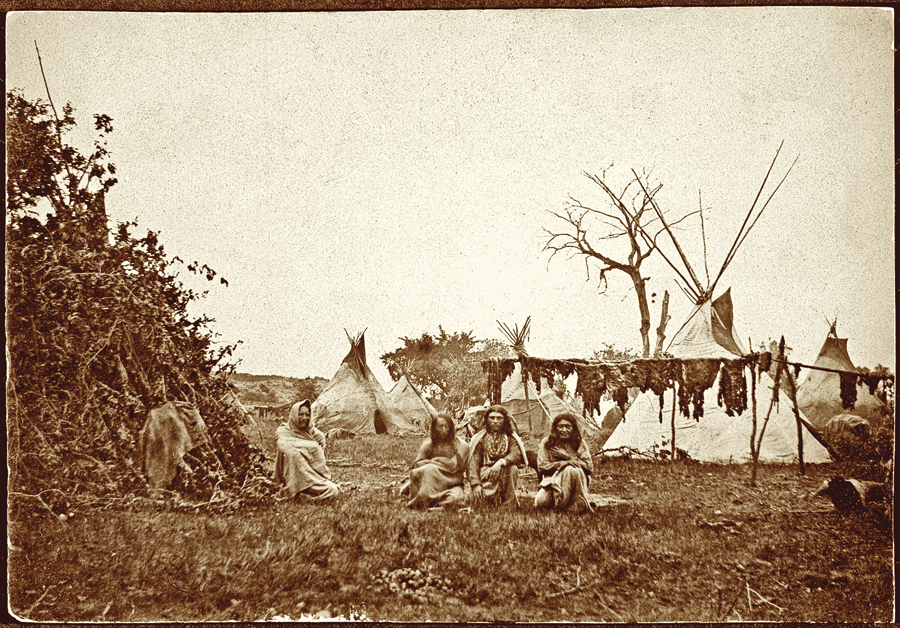

To burn through Texas to the Gulf of Mexico was a vision that came to Chief Buffalo Hump that captured the imagination of his people. During the Republic of Texas’s decade-long reign as an independent sovereignty in North America, the Comanche became the only American Indian tribe to fight its way through the giant land mass to the sea.

Peace Treaty Goes Amok

The summer of 1840 found the Comanche nation burning with an intense frenzy against anything Texian. The Penateka, the largest of the Comanche bands, had been attacking Texian ranches, which were closer to raid than Mexican haciendas. Their main goal was capturing horses, which allowed the bands to follow and hunt buffalo herds from horseback. A 56-man company of Texas Rangers, lawmen organized by the Republic of Texas in 1835, was doing its best to dissuade the band from raiding.

In January 1840, Penateka chiefs under Mukwarrah sent word to San Antonio that they wanted to discuss peace terms. The Texas Ranger in charge, Henry Karnes, agreed to a meeting at the local council house. Karnes told the messengers the chiefs would have to bring in all their white captives. For this meeting, Texas Secretary of War Albert Sidney Johnston quickly sent emissaries to San Antonio, along with two companies of Republic troops under Lt. Col. William Fisher.

![F_TX_Texas-Rangers]](https://www.truewestmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/F_TX_Texas-Rangers.jpg)

A party of 12 chiefs rode into San Antonio on March 19, led by Mukwarrah, along with 53 warriors and women and children. They brought with them one white captive, 15-year-old Matilda Lockhart. The Penatekas had not only raped the girl, but also disfigured her by burning off her nose.

Republic emissaries guided the 12 war chiefs into the council house. The Texians immediately asked the whereabouts of the other white captives. Mukwarrah explained he did not have the authority to order other Comanche bands to give up their captives. He finished his statement with, “How do you like the answer?”

An infuriated Fisher told the translator to inform the chiefs that they were now prisoners. When the Penatekas learned the news, they rushed for the door. The infantry fired point-blank into them. Mukwarrah fatally knifed a soldier before he was killed. The surviving Penatekas broke out into the street, where they turned on their Texian hosts. One Penateka boy shot a Texas judge in the heart with a bow and arrow, killing him. In the end, 35 warriors, including three women and two children, were dead, one fled the battle and 29 were taken prisoner.

When the tribe heard of the killings and captivities, they reacted in horror. Their women screamed in mourning, with many slashing their arms and faces, and chopping off their fingers in grief. They gathered the approximately 15 captives, including Matilda’s five-year-old sister, and roasted them alive.

Fighting to the Sea

Within this charged emotional atmosphere, Buffalo Hump had his vision. (The chief’s name was not actually Buffalo Hump, but white settlers could not bring themselves to call him by his real name, Pochanaquarhip—the erection that won’t go away.) His vision saw his tribal warriors driving all the Texians into the sea and then watching as their blood washed up onshore. The Penateka and Kiowa chiefs sent out warriors to fulfill this destiny.

On August 6, Texas Ranger Ben McCulloch and his unit crossed the trail of as many as 1,000 Penateka riders heading for the Gulf Coast. The large force had penetrated Texas proper without being detected by homesteaders, who were killed before they could send an alarm to other settlers. One example of the horrendous nature of these killings was the death of Tucker Foley, who, after Comanches cut off the soles of his feet, was forced by close to 27 warriors to walk around burnt prairie for sport before they shot and scalped him.

McCulloch decided to shadow the main Penateka force, which, by his count, numbered 400 warriors and 600 camp followers. Buffalo Hump led his force in a crescent moon formation, with the horns of the moon outward, so they could envelop anyone they encountered.

Later that day, the Penatekas struck the town of Victoria. They killed 12 people in the first wave, racing down city streets as townspeople fled to rooftops. They then circled the town, stealing horses and cattle.

Victoria residents put up barricades throughout the night. Come dawn, Buffalo Hump attacked again, but this time, he and his forces were beaten back by rifle fire. Having rounded up 2,000 horses, the Penateka warriors bolted into the outskirts of town, shooting and wounding residents, before they continued down the road for Matagorda Bay. Fast behind them, 125 Texas Rangers and militia under the command of Capt. John Tumlinson were on their way with McCulloch’s Rangers.

On the road to the Gulf of Mexico, the Penatekas captured Daniel Boone’s granddaughter, Nancy Crosby, and her baby. When she could not quiet her infant, warriors speared the child in front of her. A visiting Frenchman escaped capture by climbing up into the moss-covered branches of a giant oak as painted warriors rode beneath him.

At 8 a.m., Saturday, August 8, the Penatekas struck the port of Linnville. “We were careless and supposed they were Mexican traders with a large caravan,” resident William Watts wrote of the attack.

As the tribe raced through the streets of Linnville at full gallop, residents ran into the gulf, swimming for the sailboats that were only a few hundred yards off shore. Customs inspector H.O. Watts was cut down in the water and killed. His attractive wife, Juliet, was grabbed by warriors and dragged ashore. When they could not undo her whalebone corset, they tied her onto a horse so they could take her back as a trophy.

Buffalo Hump’s vision was now fulfilled. From ship deck, Linnville residents watched as his tribe took hours slaughtering the town’s cattle in their holding pens. Then they set the town afire.

Ripe for Slaughter

Instead of continuing their vengeance raid, the warriors became distracted by the thriving port’s warehouses, filled with goods to sell in the Republic of Texas and Mexico. Finding hats, fabric, colorful ribbons, reams of cloth and fine clothing, the men tied bright ribbons to their horses’ tails and covered themselves in dress coats and tall hats. Buffalo Hump had lost control of his men. Weighed down with loot and captives, the warriors chose to return home.

Outside of Victoria, Tumlinson and his 125 men intercepted the Penatekas. He ordered his men to dismount into a classic Napoleonic hollow square. This was a suicidal move. During the time the Texians could fire and reload their percussion rifles, each Penateka horseman shot up to 12 arrows.

The tribe whirled around Tumlinson with a fury. Fortunately for the Texians, the warriors were more interested in getting home with their stolen horses than slaughtering any more Texians. Tumlinson’s force slipped away.

Four days later, scouts found the Penatekas near Plum Creek, heading northwest. A 200-strong force, with Texian civilian militia and allied Tonkawas, raced in that direction under the command of Maj. Gen. Felix Huston.

Huston also ordered his men to dismount and form a hollow square, despite warnings against doing so from experienced Indian fighter McCulloch. Again, the warriors encircled the Texian force, firing arrows and deflecting Texian fire off their thick buffalo hide shields. The Texians looked ripe for slaughter.

But then rifle fire had struck down a war chief. Two warriors dragged him off, and the Penateka attack paused.

“Now General!” shouted soldier Mathew Caldwell. “Charge ’em! They are whipped!”

Huston ordered his force to charge on horseback. Screaming as they advanced toward their enemy, so as to engage in close combat, the Texians held their fire until they were upon the Penateka column. Volley fire thundered from the Texian riders, dropping 15 warriors. Their attack stampeded the captured horses.

The Penatekas panicked and ran. The Texians and Tonkawas followed them and, for 15 miles, a running battle ensued. Along the way, the Penatekas tied Crosby to a tree and shot her dead with arrows. Juliet, who was also tied to a tree and shot with arrows, survived as the arrows had deflected off her whalebone corset.

The Penatekas dropped most of their loot, but held on to what they prized most—the horse herd. They also successfully escaped with their wives and children. In the end, less than 20 dead Penatekas littered the battlefield.

One wounded Texian, Robert Hall, awoke on the battlefield to a strange sight. He recorded that some Tonkawas had dragged a dead Comanche into camp, cut small filets from his body and roasted them over an open fire before they ate the human flesh.

The Battle of Plum Creek brought forward a new way for Texians and the U.S. Army to fight raiding Comanches. It put in motion tales of Tonkawa cannibalism, and it was the last time the Comanches took a major Texian town. Linnville never recovered, as most of its residents moved southwest to settle today’s Port Lavaca. Buffalo Hump continued to raid white settlements, although he did form a friendship with a fiery German that resulted in an unbroken peace treaty.

Mike Coppock is a published author of Alaskan history works. He currently resides in Enid, Oklahoma, and he teaches in Tuluksak, Alaska, part of the year.