Two open-top and solid-frame designs reigned supreme in the age of percussion revolvers, and each type had its advantages and drawbacks.

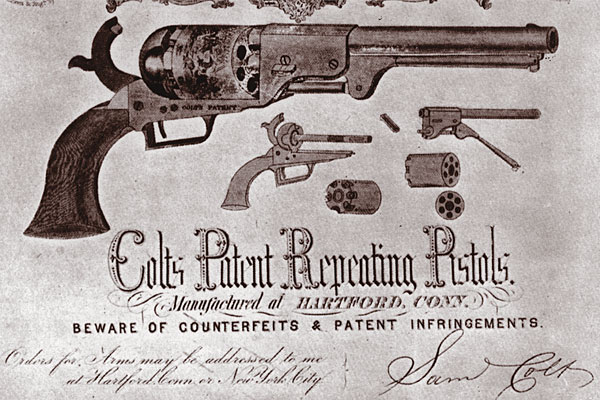

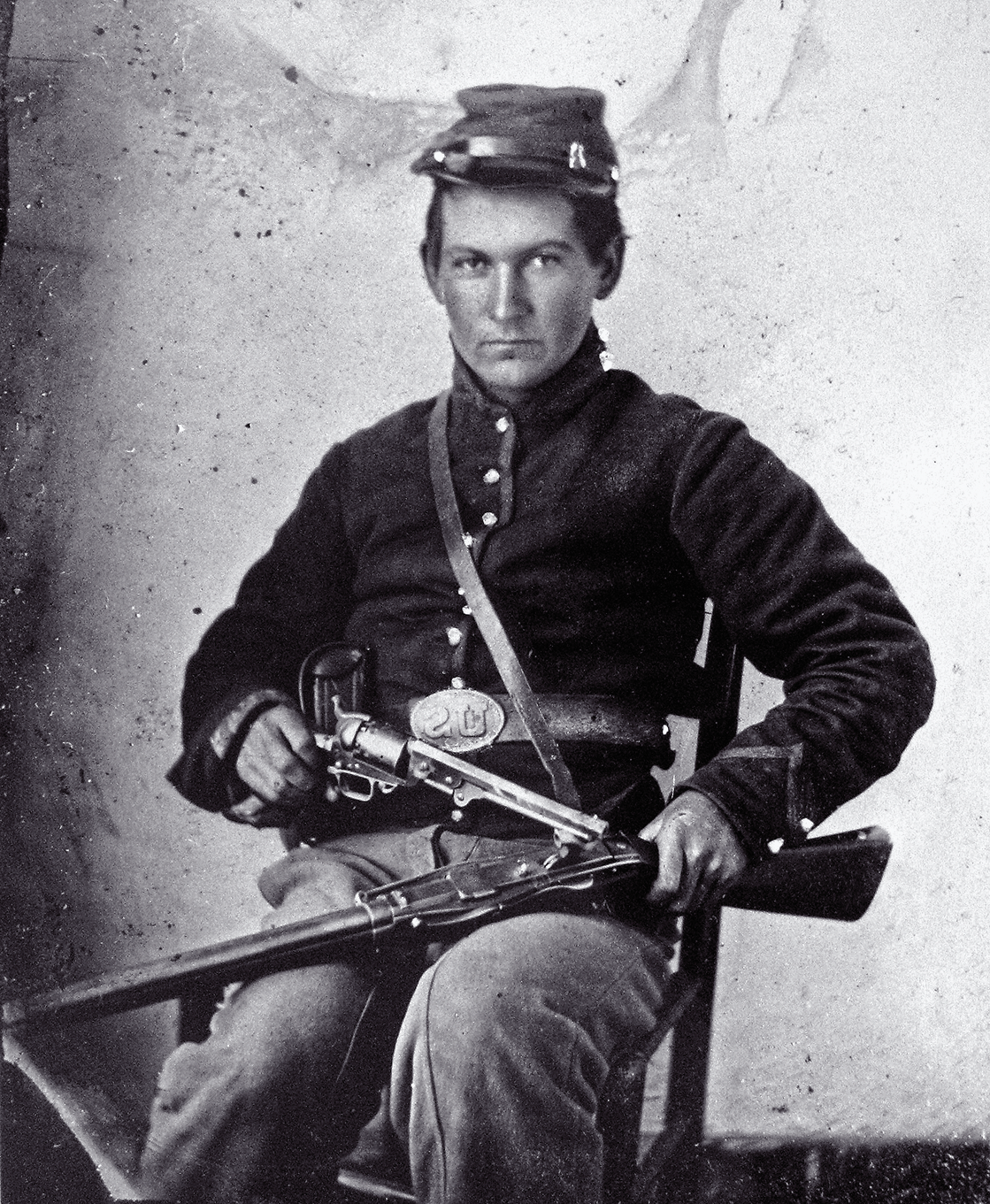

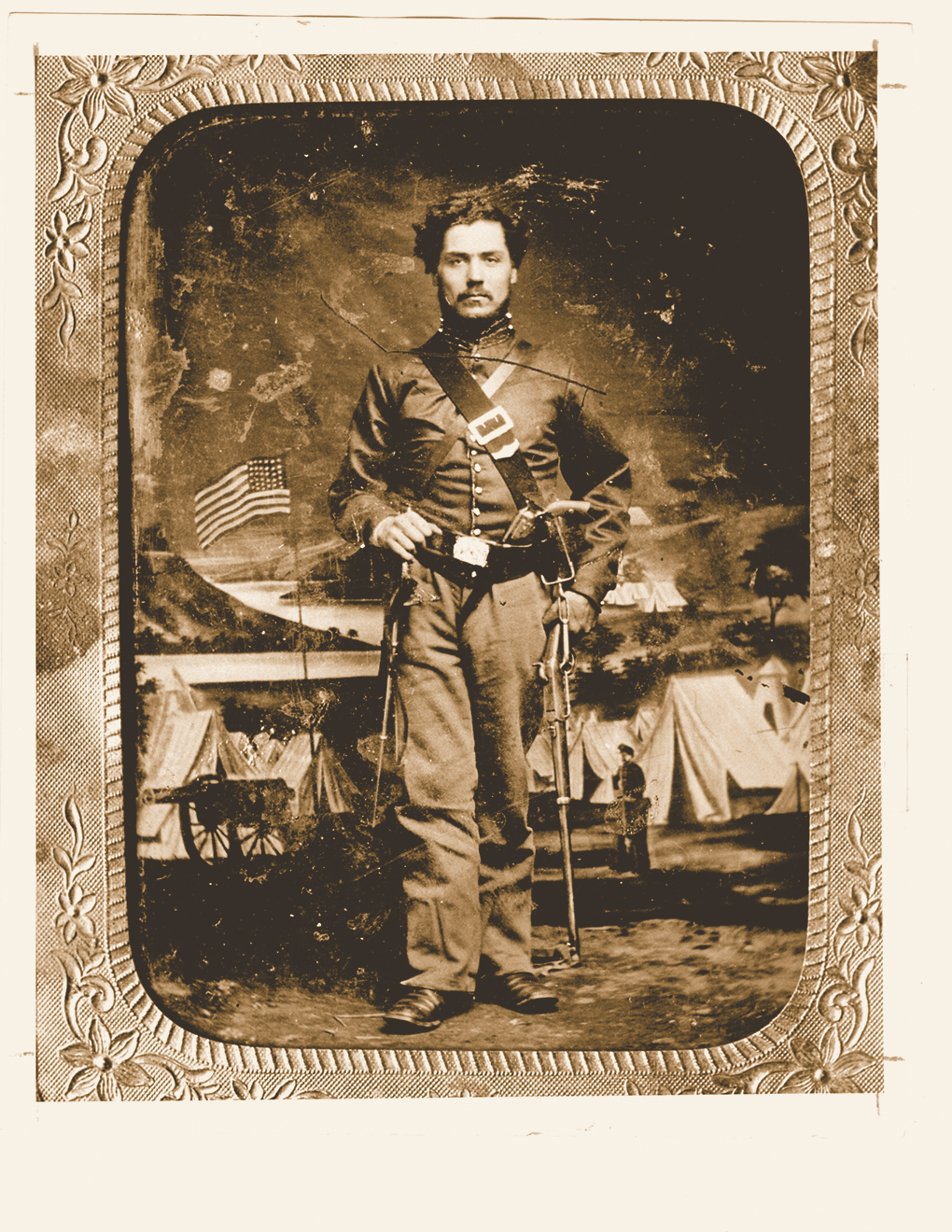

Among the many revolver producers during the mid-19th century two firearms manufacturers reigned as hands-down favorites with the American military and the public. Despite other reliable six guns—Starr revolvers, the Whitney, and others from Savage, Cooper, Bacon the Massachusetts Arms Company, various British Adams, Kerr revolvers, and France’s Lefaucheux pinfires—the undisputed top companies were Colt and Remington, each with a radically different frame design concept.

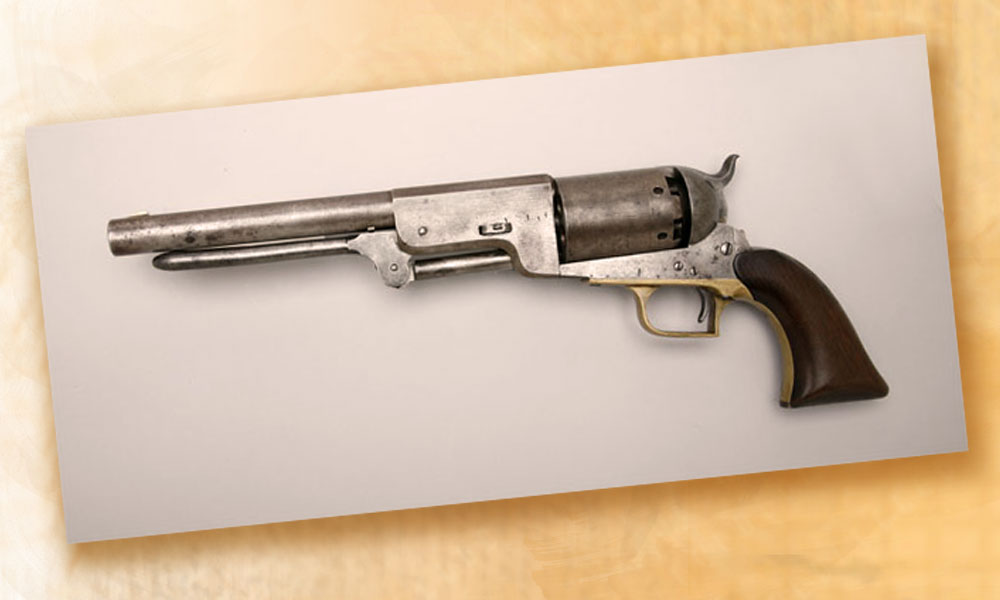

Colt made open-top revolvers with no top strap on the frame. Its six-shooters, starting with the Paterson, and continuing with the Walker, the Dragoons, the 1851 and 1861 Navys, the 1860 Army revolver and other smaller pocket arms, were open-tops, with frames consisting of just the lower and rear sections. The Colt’s cylinder base pins (then called the arbors) were large, rounded, grooved shafts that allowed for black powder carbon buildup. These arbors were permanently affixed to each arm’s recoil shield. Although it wasn’t necessary for reloading, removing the cylinder from an open-topped Colt consisted of knocking out the small wedge that locked the barrel and rammer assembly to the frame. A notch in the forward end of the hammer served as the gun’s rear sight.

Remington, on the other hand, produced revolvers with solid frames and top straps. Most of the arm’s working parts were contained in that one-piece frame. The Beals’ Army and Navy, the 1861, and New Model 1861 Army and Navy models, the New Model Belt single actions and Rider double-action revolvers were all produced in that manner. The grooved top strap of the Remington’s solid frame added strength and served as a rear sight. The cylinder base pin on Remington’s various revolvers was a slender shaft, which also permitted black powder carbon buildup. Removing a Remington’s cylinder base pin simply involved lowering the loading lever, then withdrawing the base pin from the front of the frame.

While both revolvers were favored by their users, as evidenced by the numbers produced, each had certain advantages and drawbacks. For instance, Colt’s larger grooved arbor (base pin) allowed for much more buildup of burnt powder than did the Remington’s spindly center pin. It’s been this shooter’s experience that in live fire, Colts could be fired more times than Remingtons before cylinder drag caused by carbon buildup was felt.

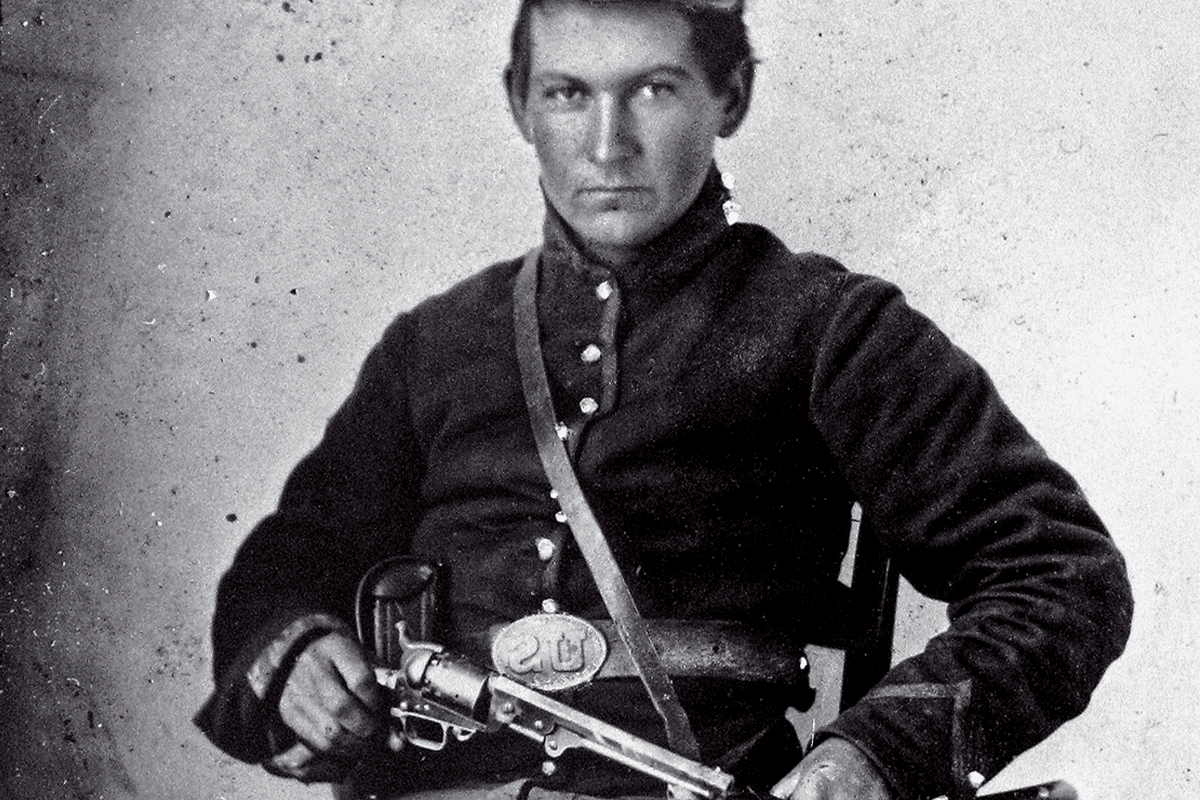

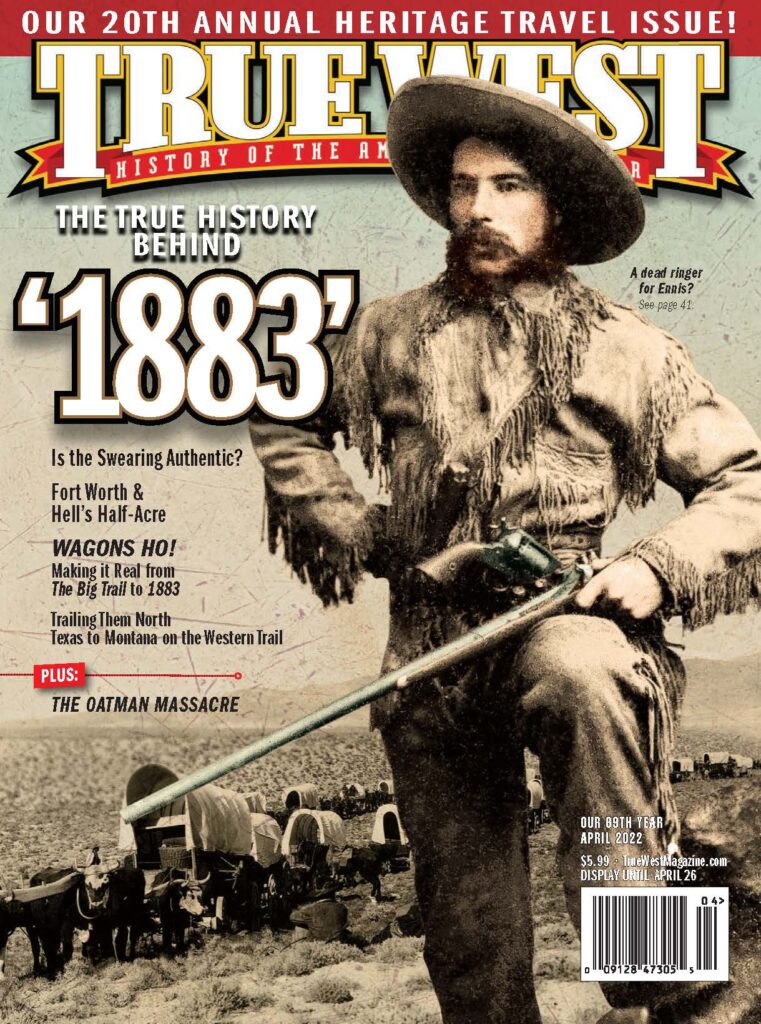

Courtesy Phil Spangenberger Collection

With Remingtons, cylinder drag can occur before all six rounds are fired. This shooter has found that to wipe a fouled cylinder pin clean, removal of the Colt’s barrel and rammer assembly—despite knocking out the wedge—is generally easier and quicker than removing the Remington’s attenuate pin. Solid-frame revolvers can sometimes be quite difficult. However, historically, most mounted combat scenarios didn’t last beyond the firing of a few shots, thus this might not have been as troublesome in a serious skirmish, as it might be to a modern pleasure shooter, or a blank charge-firing reenactor.

Due to the top strap design, the Remington revolver was considerably stronger than the Colt, and the Remington’s grooved top strap rear sight aided in accuracy, as compared to the Colt’s falling hammer rear sight (during firing). Another negative to the open-top design was that unless the muzzle of a Colt was raised between shots, the exploded percussion cap from the previous shot could roll down the hammer/frame channel and lodge itself in the gun’s inner workings. This requires immediate maintenance—not a desirable trait in a fight! The Remington’s hammer struck the percussion cap through the solid frame’s small slot and suffered no such problem.

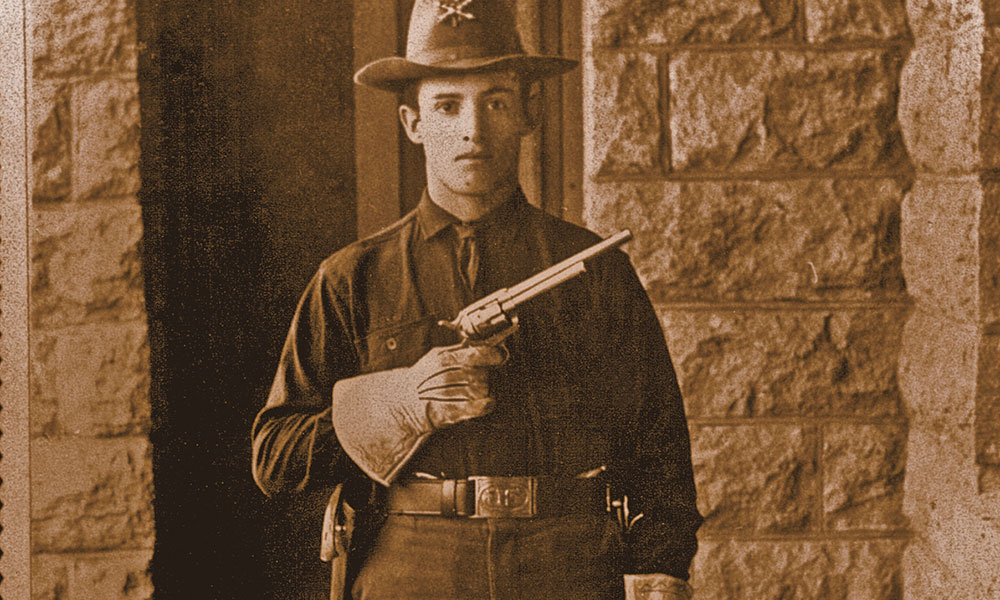

Regardless of which gun was preferred, open-top Colt or solid-frame Remington, then as now, fighting men and sport shooters have their preferences, and put up with their chosen percussion revolver’s maladies while enjoying the advantages of each. Which is your favorite?

Phil Spangenberger has written for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor and the 2022 True Westerner of the Year.