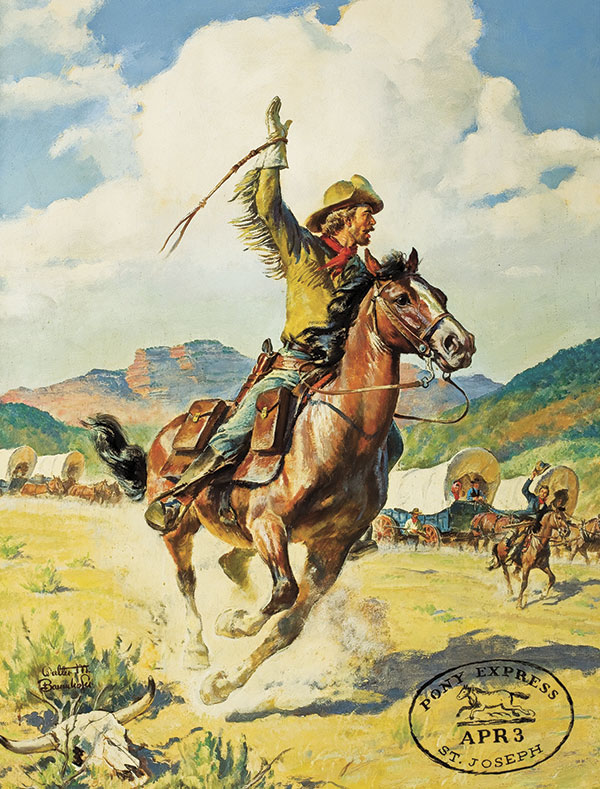

— Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma —

When America’s first Pony Express rider set off on April 3, 1860, from St. Joseph, Missouri, launching a coast-to-coast transfer of news and messages that would take 10 days instead of months to arrive, pioneers hailed the news with joy.

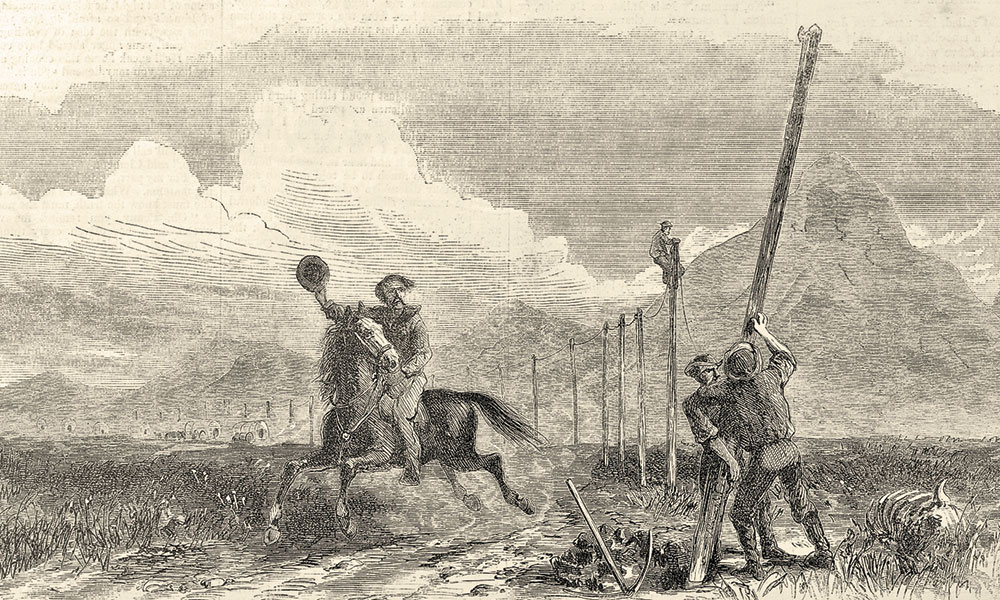

Yet what seemed so monumental in 1860 was already old news in 1861. The telegraph promised instant communication. Instead of riders racing back and forth with your news, a series of electric current pulses would transmit messages over wires.

But first those wires needed to be strung across the nation. And thus, the Pony Express rider remained a vision of death-defying courage crossing the prairies and deserts when one steamboat pilot struck out on his stagecoach journey, abandoning his Mississippi River life to travel across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains. On his way to his destination in Nevada Territory, this adventurer came face to face with destiny.

— George M. Ottinger’s 1867 wood engraving courtesy Library of Congress —

“In early August 1861, near what is now Mud Springs in remote western Nebraska, Twain saw an Express rider,” so said Christopher Corbett, author of Orphans Preferred, at this summer’s Western Writers of America convention in Kansas City, Missouri.

Corbett continued to set the scene: “The stagecoach driver had been promising him that he would see one, and Twain had taken to riding on top of the coach to take in the view, wearing only his long underwear. The entire encounter took less than two minutes.

“Writing entirely from memory (with his brother’s diary to stimulate him) in Hartford, Connecticut, 10 years later, Twain wrung an entire chapter of Roughing It from that moment. He thus initiated what many a chronicler would continue after him: he preserved the memory of the Pony, with perhaps a little embellishment.”

Of course, when the budding journalist was traveling on that stagecoach to Nevada Territory, he wasn’t yet known by his nom de plume. He was still Samuel Clemens. But by the time Roughing It got published in 1872, the world knew him as Mark Twain.

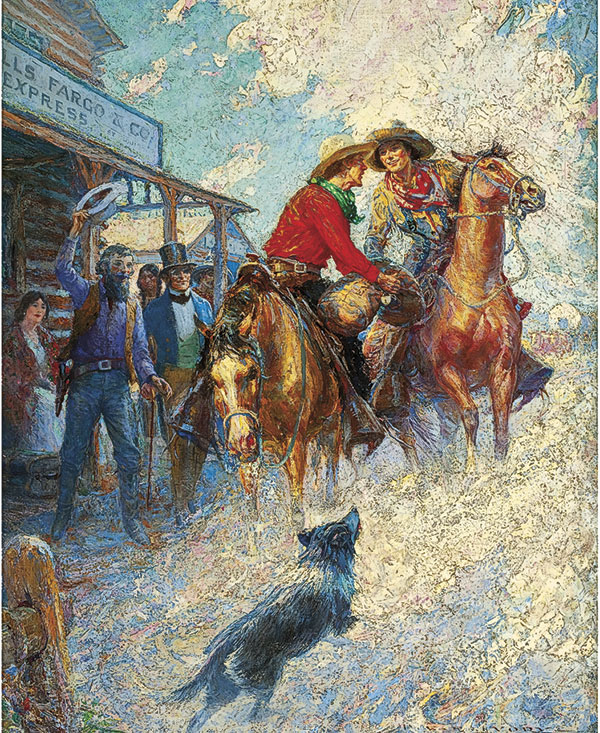

— Courtesy Heritage Auctions, March 1-2, 2012 —

No Stetson, No Pistol, No Buckskins?

In his humorous American travelogue Roughing It, a favorite book of many to this day, Twain gave one of the most noteworthy descriptions of Pony Express riders, clothed differently than how they are popularly pictured.

“The rider’s dress was thin, and fitted close; he wore a ‘round-about,’ and a skull-cap, and tucked his pantaloons into his boot-tops like a race-rider.

“He carried no arms—he carried nothing that was not absolutely necessary, for even the postage on his literary freight was worth five dollars a letter….

“His horse was stripped of all unnecessary weight, too. He wore a little wafer of a racing-saddle, and no visible blanket.

— Reproduction mochila Courtesy Smithsonian National Postal Museum —

“He wore light shoes, or none at all. The little flat mail-pockets strapped under the rider’s thighs would each hold about the bulk of a child’s primer.”

Isn’t that kind of shocking? An actual Pony Express rider did not wear a big ’ol cowboy hat—he wore a skull cap! He did not wear a fringe coat, nor did he carry a pistol! And his saddle didn’t have bulging mail packets on the side!

What seems odd at first, only because of numerous artistic representations that contradict the description, actually makes sense when one remembers: the lighter the ride, the faster the speed.

One of the partners behind the Pony Express, Alexander Majors, explained the saddle’s slim pockets, in his 1893 autobiography, Seventy Years on the Frontier.

The business letters and press dispatches were printed on tissue paper, which allowed for a light weight required for transporting the mail quickly via horses (usually a thoroughbred on the Eastern route and a mustang for the rugged Western terrain). The weight was fixed at 10 pounds or under; each half of an ounce cost $5 in gold to transport.

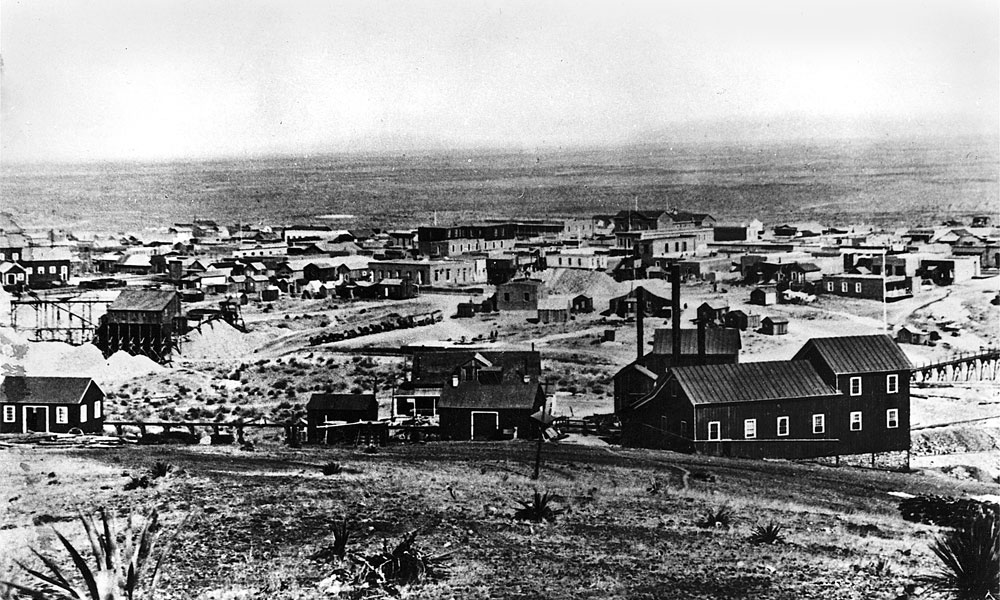

— True West Archives —

A rider’s desire to keep the weight as light as possible also explained why Twain’s rider didn’t carry a gun.

“Along a well-traveled part of the trail (as where Twain encountered him), a rider wouldn’t have to think about carrying a gun,” says Paul Fees, the retired curator from the Buffalo Bill Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming.

“At night, or through more dangerous territory, I suspect he would arm himself. The revolver of choice, apparently, was the Colt Model 1849 percussion pocket revolver in .31 caliber.”

Now we know why the 80 chosen to be riders were called the “pick of the frontier.” To put your life on the line so you could faithfully meet the 10-day schedule required grit and gumption. Yet Pony riders must have felt the gamble was worth the gig; their $50 a month salary was good pay in the days when a skilled blacksmith made $33.

Okay, so we’re making the mochila lighter and, for the most part, tossing any firearms, but what about the attire? Would a Pony Express rider really go without his cowboy hat, his boots and his buckskins?

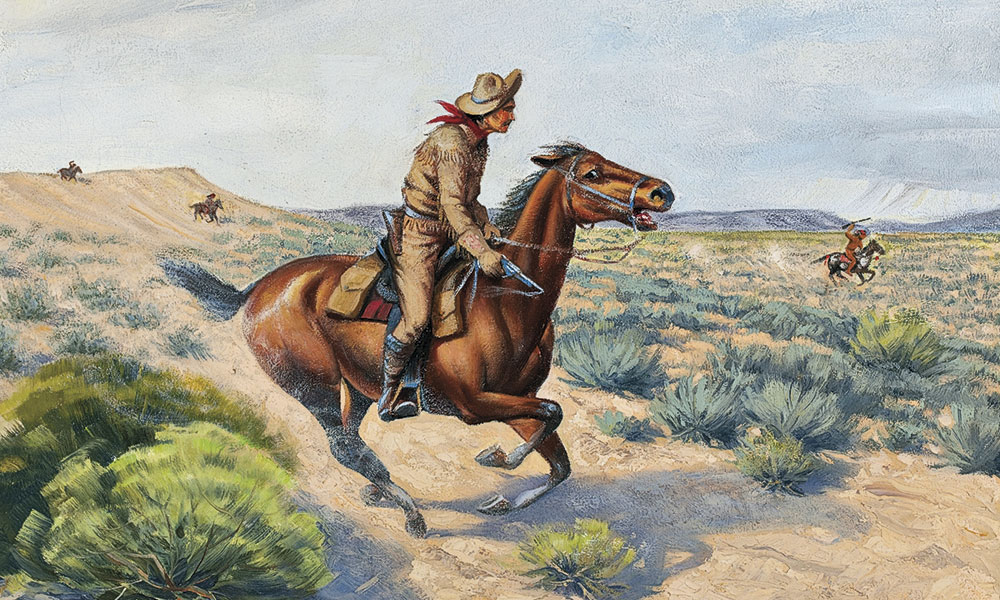

— True West Archives —

Dressing for Success

Hold your horses! Your notion of what that Pony Express rider looked like during his short-lived yet impressive career may still be somewhat accurate. Although one aspect does not appear to be true to history at all.

“Boots were the main footwear, although it wouldn’t be out of line for some riders to wear leather moccasins if they had them as normal footwear,” says Elanna “Quackgrass Sally” Skorupa, who has ridden the Pony Express trails for more than 25 years and is the only member of the National Pony Express Association to belong to all eight state divisions (she even carried the Olympic torch for the Pony Express!).

The clothing changed with the seasons and was as varied as the riders themselves, Skorupa says, adding, “Hats of all shapes and styles would have been worn…. Wool, calico and cotton shirts, wool britches and homespun sackcloth would have been the norm. I have heard mention of some gloves and even perhaps some gauntlets, but these were very young men, so their personal items would have been few.”

Twain’s rider just had a penchant for a skull cap over a cowboy hat and light shoes over boots. And instead of a buckskin fringe coat, he wore a…round-about? That’s not such a familiar term.

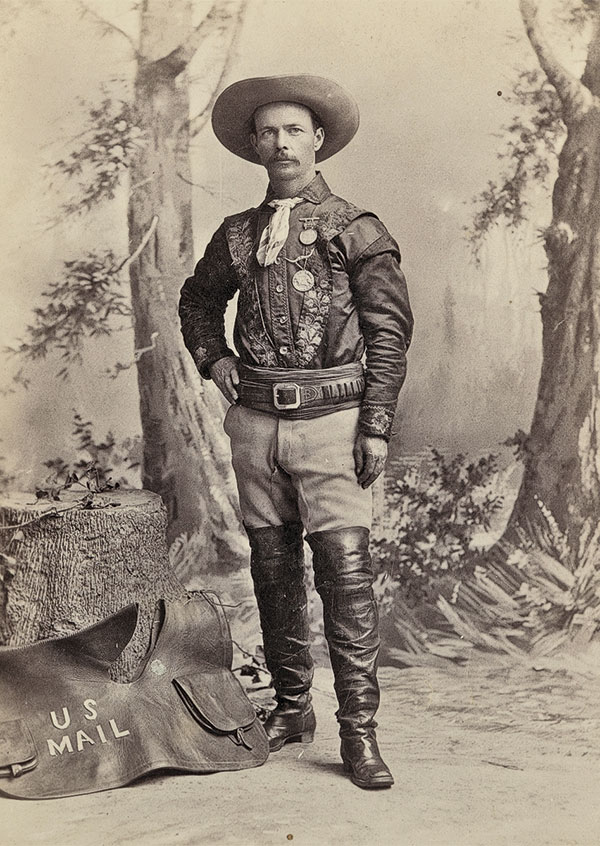

— Johnson photo courtesy Heritage Auctions, December 11-12, 2012 —

Turns out, a round-about is a fitting choice for someone looking to literally lighten the load on his shoulders. It is a short, close-fitting jacket. Readers may be familiar with the ornate version of this jacket, worn by U.S. Dragoons of the Antebellum era, military historian John Langellier says.

Picturing Twain’s Pony rider in a short jacket, tucked-in pants, light shoes, skull cap and minus a pistol may make logical sense. (And he possibly wore boots. Twain was contradictory on this point. Perhaps his rider changed footwear for the terrain?) Each rider’s style adjusted with the seasons and topography, and beyond that, he wore what felt comfortable and light for the task at hand.

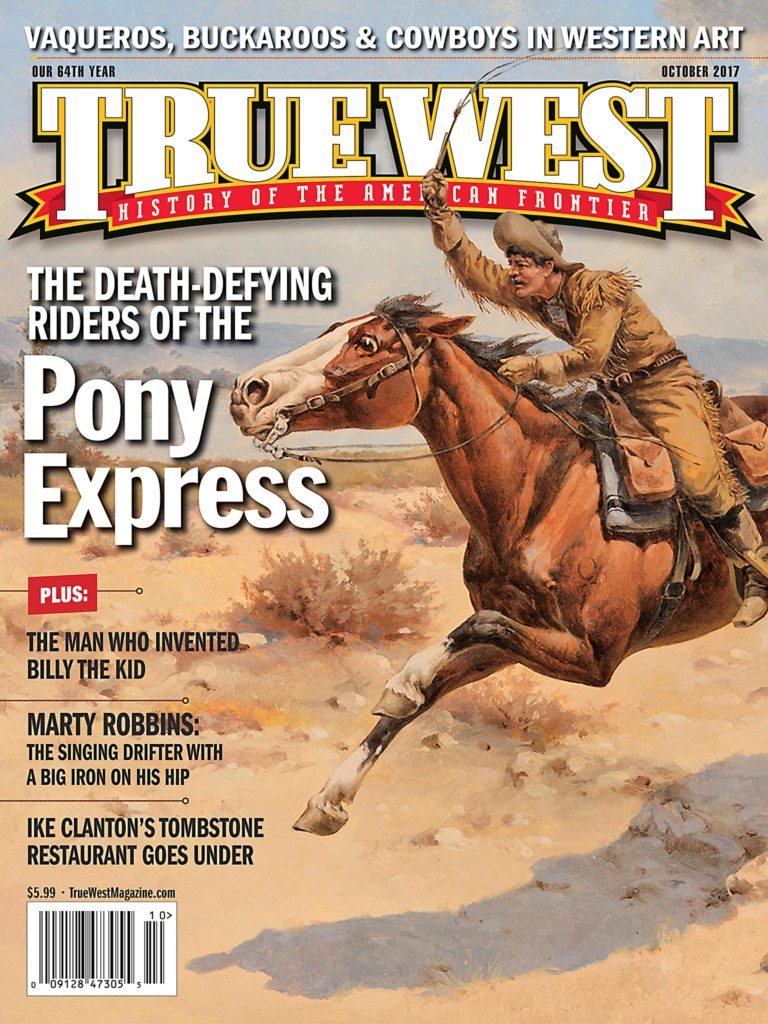

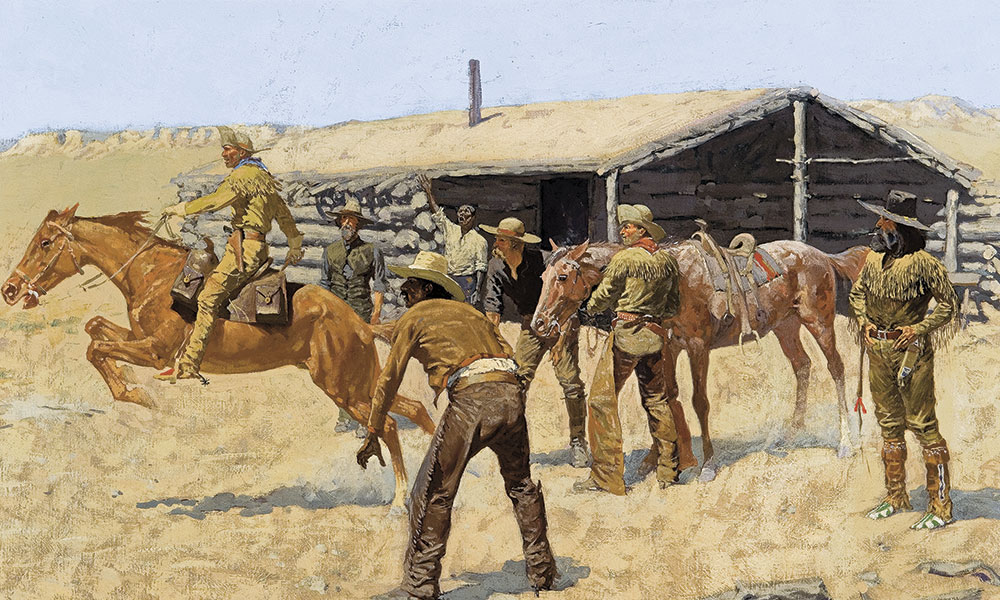

Yet getting Twain’s rider to gallop in the Pony Express movie in our minds may prove difficult. After all, the popular idea of how a Pony Express rider should look is best portrayed in Frederic Remington’s The Coming and Going of the Pony Express. His Pony Express rider is superbly clad in a buckskin suit, with his cowboy hat flared up to the sky and his trusty pistol strapped to his waist.

But the master cowboy artist got this attire wrong.

— Courtesy C.M. Russell Museum Benefit Auction, March 18-19, 2016 —

Romancing the Pony

“I have seen several artists clothe these riders in buckskins,” Skorupa says, “and usually the Pony Express rider is portrayed older than the young age of the true riders.”

Then she twists the knife in: “I have never found any evidence of the riders wearing buckskins.”

Oh, say it’s not so. Yes, the artist was a New Yorker, but his bloodlines link him to the esteemed American Indian portrait artist George Catlin, to the founder of Remington Arms Eliphalet Remington, to Mountain Man Jedediah Smith and even to our country’s first president, George Washington. He’s not the caliber to swap the real for the mythic!

When actually, that’s somewhat Remington’s appeal as an artist. When he tried out sheep ranching in Kansas in 1883, he found the work boring and rough. He was more of a pseudo-cowboy. He had real-life adventures that gave him an honest connection to the frontier world he was depicting, but you could never call him a bona fide frontiersman. His style was more hearty and breezy than scrupulous, and if he wanted his Pony Express rider to wear a buckskin suit, then truth be damned.

— Courtesy Heritage Auctions, October 15-16, 2010 —

Even so, Remington paid proper homage to the Pony Express rider’s history. In the dead of winter, blinding snow all around him, his rider gallops off, having just changed his horse at one of the relay stations that made the endeavor such a success (the stops gave both horses and riders time to rest without gaps in the service of delivering the mail). All the inappropriate weight the artist threw onto his rider clothing-wise, he more than made up for in the overall tone that these riders were boys and young men to admire, who set forth in any kind of weather, in unforeseen worlds of danger, to do a job well done.

Perhaps Remington and all the others who clothed these daring riders in buckskins were paying too much attention to “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s portrayal of them.

“For three decades a representation of the Pony Express was a spectacle at every performance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West,” Buffalo Bill biographer Don Russell wrote. “No other act was more consistently on its program. It was easy to stage, and it had the interest of a race, as well as re-creating a romantic episode.”

Russell pointed out that “almost nothing was written about [the Pony Express] for half a century after its brief existence” and later added, “It is highly unlikely that the Pony Express would be so well remembered had not Buffalo Bill so glamorized it; in common opinion Buffalo Bill and Pony Express are indissolubly linked.”

— Courtesy Heritage Auctions, December 9, 2009 —

Remington would have known of Buffalo Bill’s Pony Express presentation. He studied the Wild West show cast for his illustration published in Harper’s Weekly on August 18, 1894. He, like many Americans, undoubtedly saw Buffalo Bill as a buckskin-clad Pony Express rider on the September 19, 1888, cover of Beadle’s Dime New York Library.

We should forgive Remington for his buckskin suit rider, even as we reshape our world view to imagine one of these brave souls wearing a skull cap instead of a cowboy hat. After all, without the romance, would we even remember these Pony Express riders today?